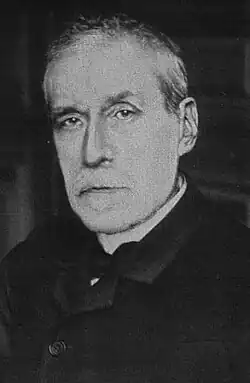

Émile Boutroux

Étienne Émile Marie Boutroux (28 July 1845 – 22 November 1921) was a French philosopher and historian of philosophy.

Quotes

La natura e lo spirito

- Émile Boutroux, La natura e lo spirito, translation by G. Papini, Carabba Editore, Lanciano, 1920.

- The distinctive feature of Medieval philosophy, which reached its peak in scholasticism, is the effort to use reason to demonstrate a set of metaphysical doctrines capable of connecting, as far as possible, Hellenic philosophy of nature and Christian theology. While Greek philosophy started from the idea of a nature entirely permeated by the divine and subsequently fell due to the dissociation of these two principles, Scholasticism, for which the divine is essentially infinite personality and perfection, first radically separates God and nature and grants the latter only the attributes indispensable to a contingent existence. Nothing then prevents us from conceiving of perfect divine spirituality as coexisting with imperfect nature. Transcendent with respect to things, God is not affected by their imperfection. And the very imperfection of nature provides reason with the starting point for the arguments by which it establishes the philosophical truths implied in supernatural truths. Thus, the conditions of a natural philosophy were reconciled with those of a religious philosophy. (La scolastica, pp. 10-11)

- Mysticism consists, according to a beautiful definition I find in Plotinus], in seeing with closed eyes [...] in seeing with the eyes of the soul, while the eyes of the body are closed. The essential phenomenon of mysticism is what is called ecstasy, a state in which, with all communication with the external world interrupted, the soul has the sense of communicating with an internal object, which is the infinite being, God. (La psicologia del misticismo, pp. 58-59)

- [...] the person of Ravaisson himself is like the act, the fulfilment of the thought which, in his written philosophy, aspires to realise itself. He immediately distinguished himself by a grace, a distinction, a smiling serenity that never disappeared. He attracted people with his good grace and impressed them with his fundamental affinity with the noble and the great. He spoke with absolute simplicity and probity, concerned only with thinking correctly and expressing his thoughts faithfully and naturally, without ever allowing a word of effect or rhetorical artifice to enter his mind. He spoke about everything and was interested in the small pleasures of the world as well as the great questions of philosophy and life. But in all things he saw the link between the ideal and the real. Like the ancient Greeks, he saw the divine in everything. (La filosofia di F. Ravaisson, pp. 115-116)

- Above all, [Félix Ravaisson] was a writer. He expressed himself in broad, flexible, simple and wise phrases, elegant and solid with an air of abandon, and the logical relationships between ideas and the aesthetic harmony that coordinates them and the creative action that brings forth the details, conditions and elements from the whole and from the beginning. His style is the very soul grasped in his inner life and in the secret movement through which it gives itself and spreads. (La filosofia di F. Ravaisson, p. 116)

- The whole person of Ravaisson was the manifestation of one unique thing: his intimate union of thought and heart with spiritual and eternal realities. Deep down, he did not believe in death because he was convinced that what passes away has its being only in what remains. He saw things and people not only in their ideas, like Plato, but in their source, which is infinite love, superior to the Idea and unfailing. He not only professed his doctrine with conviction, but lived it. (La filosofia di F. Ravaisson, p. 116)

Socrate

- Émile Boutroux, Socrate, translation by Teresa Morselli, Edizioni Athena, Milano, 1929.

Incipit

- A philosopher is a man who compares the knowledge and beliefs of men in order to investigate their relationships; therefore, we want to know how Plato or Leibniz conceived these relationships; Furthermore, since a philosopher is not a seer to whom truth is revealed in a flash, but a patient researcher who reflects, criticises, doubts, hesitates, and surrenders only to obvious reasons, we want to know by what methodical means, by what observations and reasoning our author arrived at his conclusions. For this is not a matter of unconscious and mechanical work of his brain, but of a conscious and deliberate effort to overcome the limits of his own personality, to think universally, and to discover the truth. (Ch. I, p. 7)

Quotes

- [...] the history of philosophy deals with the doctrines conceived by philosophers, not philosophy in general in its entirety, nor the psychological evolution of each thinker in particular; therefore, its essential task, to which all others are subordinate, consists in penetrating and understanding doctrines, explaining them as well as possible, as the author himself would do, and presenting them in accordance with the spirit and, to a certain extent, the style of their author. (Ch. I, pp. 7-8)

- Socrates' condemnation of ancient physics has its root cause in the ideas inherent in his own nation. Greece could not fully identify with the speculations on the principles of things to which the physiologists had gone. Without doubt, the power of reasoning, the ingenious subtlety, and the marvellous sense of harmony employed by these profound investigators were its heritage; but the immediate application of these spiritual qualities to material objects so foreign to man was contrary to the genius of an essentially political race, especially fond of fine words and fine deeds. (Ch. II, p. 22)

Quotes about

- Boutroux [...] believes he is criticising science, but instead he criticises a puppet of formal logic, as if the logical power of thought were exhausted in the principle of identity, A is A; but conversely, he establishes a dogmatism worse than the scientific one (because it is philosophical) by considering all reality as a posteriori of experience. (Guido De Ruggiero, La filosofia contemporanea, Editori Laterza, Bari, 19648, part II, Ch. IV, p. 192)

- Scientific laws, says Boutroux, result from the collaboration of the spirit and things; they are the product of the activity of the spirit applied to a foreign matter; and they represent the effort that the spirit makes to establish a coincidence between things and itself. But what coincidence is this, where it is not known with what thought must coincide? He rightly says that the highest forms of reality cannot be resolved into the lowest; but then he resolves into the lowest... precisely thought, that is, the very thought that alone can make us understand progress from below to above. Consequently, progress is clouded in the void of contingency, and all forms of reality become things in themselves, which thought can do nothing but shadow in its concepts, trying in vain to adapt to them. (Guido De Ruggiero, La filosofia contemporanea, Editori Laterza, Bari, 19648, Part II, Ch. IV, p. 191)

- The main core around which Boutroux's thought revolves is the problem of science and the meaning of natural laws. From 1874, the year of his thesis, “De la Contingence des lois de la Nature”, until his death, i.e. for just under half a century, Boutroux developed and elaborated his critique of science, always insisting on it and basing his theories on freedom and religion on it, which form, one might say, the positive part of his philosophy. (Ugo Spirito, Il pragmatismo nella filosofia contemporanea, Vallecchi Editore, Firenze, 1921, cap. II, p. 142)

- In the continuous development of nature and spirit, Boutroux believes it is impossible to establish anything definitive that has eternal value. Man, therefore, who is the greatest exponent of progress, does not know what his progress is tending towards; he does not know, therefore, whether his progress is true progress. Everything disappears into the indeterminate, into confusion, and the sceptical conclusion presents itself as compelling. But no: Boutroux, like James before him, does not lose himself in negation at this point and wants to save himself from scepticism. And so negation itself is transformed into affirmation. It is precisely the indistinct, the confused that contains the reason for life: in it is love, faith, the ideal; in it is that powerful impulse that moves the poet, the artist, the scientist himself, for science would be nothing without faith. But religion thus attained is an empty religion, and the ideal thus established is an ideal that fades into nothingness. (Ugo Spirito, Il pragmatismo nella filosofia contemporanea, Vallecchi Editore, Firenze, 1921, cap. II pp. 150-151)

- Cesare Ranzoli, Boutroux, Edizione Athena, Milano, 1924.

- He used to say that a philosophical system is a living thought; and, in truth, he not only taught his philosophy, but lived it, felt it, spread it and defended it in books and with words, in Europe and America, regardless of hardship, with all the ardour of a missionary.

- Poor health, which worsened with the passing of the years, forced him from his youth to withdraw into himself, to seek in his own spirit the best source of joy. Few penetrated his moral intimacy. But just seeing him like that, tall, pale, thin, emaciated, it was easy to guess what a rich inner life was enclosed in that frail body, and how the world of the spirit must have been the only real world for him.

- For many years, the clergy of the parish of Saint-Etienne-du-Mont cherished the memory of that pale teenager, who never missed divine services and zealously fulfilled all religious practices. In turn, Boutroux never forgot the church of his first communion, the church where his spirit had been nourished and strengthened in those religious convictions that were to form the basis and crowning glory of his philosophical views. As an adult, he returned there more than once to recall the sweet memories of his younger years and to meditate at the tomb of Blaise Pascal.