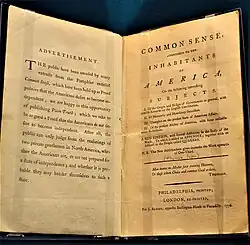

Common Sense

Common Sense is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies.

Quotes

- Sourced from the 6th ed. (Philadelphia, 1776)

- Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages, are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favour; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defence of custom. But the tumult soon subsides.—Time makes more converts than reason.

- Introduction (p. 3)

- The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind. Many circumstances hath, and will arise, which are not local, but universal, and through which the principles of all lovers of mankind are affected, and in the event of which their affections are interested. The laying a country desolate with fire and sword, declaring war against the natural rights of all mankind, and extirpating the defenders thereof from the face of the earth, is the concern of every man to whom nature hath given the power of feeling; of which class, regardless of party censure, is the author.

- Introduction (p. 3)

- Who the Author of this Production is, is wholly unnecessary to the Public, as the Object for Attention is the Doctrine itself, not the Man. Yet it may not be unnecessary to say, That he is unconnected with any Party, and under no sort of Influence public or private, but the influence of reason and principle.

- Introduction (postscript)

- Some writers have so confounded society with government, as to leave little or no distinction between them; whereas they are not only different, but have different origins. Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness; the former promotes our happiness positively, by uniting our affections; the latter negatively, by restraining our vices. The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions. The first is a patron, the last a punisher.

- Of the Origin and Design of Government in general, with concise Remarks on the English Constitution (p. 5)

- Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one: For when we suffer, or are exposed to the same miseries by a government, which we might expect in a country without government, our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence; the palaces of Kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of Paradise: For were the impulses of conscience clear, uniform and irresistably obeyed, man would need no other lawgiver; but that not being the case, he finds it necessary to surrender up a part of his property, to furnish means for the protection of the rest; and this he is induced to do, by the same prudence which in every other case advises him, out of two evils to choose the least. Wherefore, security being the whole design and end of government, it unanswerably follows, that whatever form thereof appears most likely to ensure it to us, with the least expence and greatest benefit, is preferable to all others.

- Of the Origin and Design of Government... (p. 5)

- There is something exceedingly ridiculous in the composition of Monarchy; it first excludes a man from the means of information, yet empowers him to act in cases where the highest judgment is required.

- Of the Origin and Design of Government... (p. 8)

- How came the King by a power which the People are afraid to trust, and always obliged to check? Such a power could not be the gift of a wise people, neither can any power which needs checking be from God: Yet the provision which the constitution makes, supposes such a power to exist. But the provision is unequal to the task; the means either cannot or will not accomplish the end, and the whole affair is a felo de se: For as the greater weight will always carry up the less, and as all the wheels of a machine are put in motion by one, it only remains to know which power in the constitution has the most weight, for that will govern: And though the others, or a part of them, may clog, or, as the phrase is, check the rapidity of its motion, yet so long as they cannot stop it, their endeavours will be ineffectual: The first moving power will at last have its way, and what it wants in speed is supplied by time.

- Of the Origin and Design of Government... (p. 8)

- In the early ages of the world, according to the scripture chronology, there were no Kings; the consequence of which was, there were no wars; it is the pride of Kings which throws mankind into confusion.

- Of Monarchy and hereditary Succession (p. 9)

- But there is another and greater distinction, for which no truly natural or religious reason can be assigned, and that is, the distinction of Men into Kings and Subjects. Male and female are the distinctions of nature—good and bad the distinctions of Heaven; but how a race of men came into the world so exalted above the rest, and distinguished like some new species, is worth enquiring into, and whether they are the means of happiness or of misery to mankind.

- Of Monarchy and hereditary Succession (p. 9)

- Government by Kings was first introduced into the world by the Heathens, from whom the children of Israel copied the custom. It was the most prosperous invention the devil ever set on foot for the promotion of idolatry.

- Of Monarchy and hereditary Succession (p. 10)

- For all men being originally equals, no one by birth could have a right to set up his own family in perpetual preference to all others for ever; and though himself might deserve some decent degree of honors of his cotemporaries, yet his descendents might be far too unworthy to inherit them.

- Of Monarchy and hereditary Succession (p. 12)

- Men who look upon themselves born to reign, and others to obey, soon grow insolent—selected from the rest of mankind, their minds are easily poisoned by importance; and the world they act in differs so materially from the world at large, that they have but little opportunity of knowing its true interests, and when they succeed in the government are frequently the most ignorant and unfit of any throughout the dominions.

- Of Monarchy and hereditary Succession (p. 14)

- Of more worth is one honest man to society, and in the sight of God, than all the crowned Ruffians that ever lived.

- Of Monarchy and hereditary Succession (p. 15)

- I offer nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense.

- Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs (p. 15)

- The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. It is not the affair of a City, a County, a Province, or a Kingdom; but of a Continent—of at least one eighth part of the habitable Globe. It is not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected even to the end of time by the proceedings now. Now is the seed-time of Continental union, faith and honor. The least fracture now, will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; the wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

- Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs (p. 16)

- It is pleasant to observe by what regular gradations we surmount the force of local prejudice, as we enlarge our acquaintance with the world.

- Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs (p. 18)

- Every thing that is right or reasonable pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, 'tis time to part.

- Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs (p. 19)

- Every quiet method for peace hath been ineffectual. Our prayers have been rejected with disdain; and hath tended to convince us, that nothing flatters vanity or confirms obstinacy in Kings more than repeated petitioning—and nothing hath contributed more, than that very measure, to make the Kings of Europe absolute. Witness Denmark and Sweden. Wherefore, since nothing but blows will do, for God's sake let us come to a final separation, and not leave the next generation to be cutting throats, under the violated, unmeaning names of parent and child.

- Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs (p. 21)

- Small islands, not capable of protecting themselves, are the proper objects for government to take under their care; but there is something very absurd, in supposing a Continent to be perpetually governed by an island. In no instance hath nature made the satellite larger than its primary planet, and as England and America with respect to each other reverses the common order of nature, it is evident they belong to different systems. England to Europe: America to itself.

- Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs (p. 22)

- But where, say some, is the King of America? I'll tell you, friend, he reigns above; and doth not make havoc of mankind, like the Royal Brute of Great-Britain. Yet that we may not appear to be defective even in earthly honors, let a day be solemnly set apart for proclaiming the Charter; let it be brought forth placed on the Divine Law, the Word of God; let a crown be placed thereon, by which the World may know, that so far as we approve of Monarchy, that in America the Law is King. For as in absolute governments the King is Law, so in free countries the Law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other. But lest any ill use should afterwards arise, let the crown at the conclusion of the ceremony be demolished, and scattered among the people, whose right it is.

- Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs (p. 26)

- I have never met with a man, either in England or America, who hath not confessed his opinion, that a separation between the countries would take place one time or other: And there is no instance in which we have shewn less judgment, than in endeavoring to describe what we call the ripeness or fitness of the Continent for independence.—As all men allow the measure, and vary only in their opinion of the time, let us, in order to remove mistakes, take a general survey of things, and endeavor if possible, to find out the very time. But I need not go far, the enquiry ceases at once, for the time hath found us. The general concurrence, the glorious union of all things, prove the fact.—It is not in numbers but in unity that our great strength lies: Yet our present numbers are sufficient to repel the force of all the world.

- Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs (p. 27)

- O ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose not only the tyranny, but the Tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the old world is over-run with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia and Africa have long expelled her.—Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.

- Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs (p. 27)

- When we are planning for posterity, we ought to remember, that virtue is not hereditary.

- Of the present Ability of America, with some miscellaneous Reflections (p. 32)

- Should an independency be brought about by the first of those means, we have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest, purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation similar to the present hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birth-day of a new world is at hand, and a race of men, perhaps as numerous as all Europe contains, are to receive their portion of freedom from the event of a few months. The reflection is awful, and in this point of view, how trifling, how ridiculous, do the little paltry cavillings of a few weak or interested men appear, when weighed against the business of a World?

- Appendix (p. 40)

- Your testimony ... tends to the decrease and reproach of all religion whatever, and is of the utmost danger to society, to make it a party in political disputes.

- Appendix (pp. 44–45)

- And here, without anger or resentment, I bid you farewell: Sincerely wishing, that as men and Christians, ye may always fully and uninterruptedly enjoy every civil and religious right; and be, in your turn, the means of securing it to others; but that the example which ye have unwisely set, of mingling religion with politics, may be disavowed and reprobated by every inhabitant of America.

- Appendix (p. 45)