REGALIA (Lat. regalis, royal, from rex, king), the ensigns

of royalty. The crown (see Crown and Coronet) and sceptre

(see Sceptre) are dealt with separately. Other ancient symbols

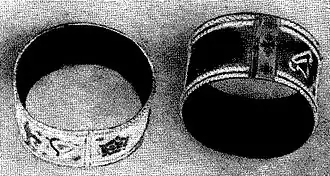

of royal authority are bracelets, the sword, a robe or mantle,

and, in Christian times, a ring. Bracelets, as royal emblems,

are mentioned in the Bible in connexion with Saul (2 Sam. i. 10),

and they have been commonly used by Eastern monarchs.

In Europe their later use seems to have been fitfully confined

to England, although they were a very ancient ornament for

kings among the Teutonic races. Two coronation bracelets

are mentioned among the articles of the regalia ordered to be

destroyed at the time of the Commonwealth, and two new

ones were made at the Restoration. These are of gold, 1½ in.

in width, and ornamented with the rose, thistle, harp and

fleur-de-lis in enamel round them. They have not been used

for modern coronations.

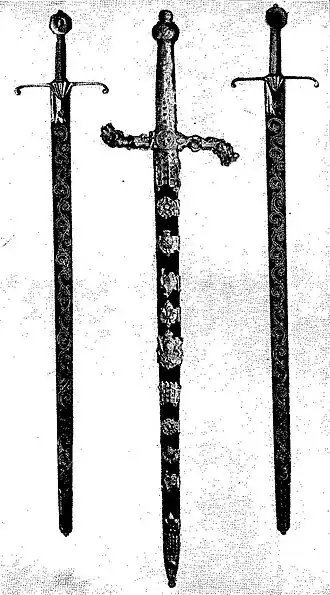

The sword is one of the usual regalia of most countries, and

is girded on to the sovereign during the coronation. In England

the one sword has been developed into five. The Sword of

State is borne before the sovereign on certain state occasions,

and at the coronation is exchanged for a smaller sword, with

which the king is ceremonially girded. The three other swords

of the regalia are the “Curtana,” the Sword of Justice to the

Spirituality, and the Sword of Justice to the Temporality.

The Curtana has a blade cut off short and square, indicating

thereby the quality of mercy.

The mantle, as a symbol of royalty, is almost universal, but

in the middle ages other quasi-priestly robes were added to

it (see Coronation). The English mantle was formerly made

of silk; latterly cloth of gold has been used., The ring, by

which the sovereign is wedded to his kingdom, is not of so wide

a range of usage. That of the English kings held a large ruby

with a cross engraved on it. Recently a sapphire has been

substituted for the ruby. Golden spurs, though included

among the regalia, are merely used to touch the king's feet,

and are not worn.

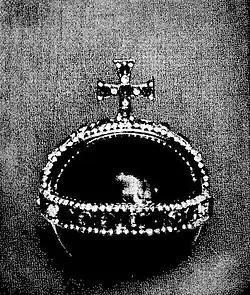

The orb and cross was not anciently placed in the king's

hands during the coronation ceremony, but was carried by

him in the left hand on leaving the church. It is emblematically

of monarchical rule, and is only used by a reigning sovereign.

The idea is undoubtedly derived from the globe with the figure

of Victory with which the Roman emperors are depicted. The

larger orb of the English regalia is a magnificent ball of gold,

6 in. in diameter, with a band round the centre edged with

gems and pearls. A similar band arches the globe, on the

top of which is a remarkably fine amethyst 1½ in. in height,

upon which rests the cross of gold outlined with diamonds.

There is a smaller orb made for Mary II., who reigned jointly

with King William III.

The English regalia, with one or two exceptions, were made

for the coronation of Charles II. by Sir Robert Vyner. The

Scottish regalia preserved at Edinburgh comprise the crown,

dating, in part, from Robert the Bruce, the sword of state

given to James IV. by Pope Julius II., and two sceptres.

Besides regalia proper, certain other articles are sometimes

included under the name, such as the ampulla for the holy oil, and

the coronation spoon. The ampulla is of solid gold in the form of

an eagle with outspread wings. It weighs 10 oz., and holds 6 oz.

of oil. The spoon was not originally used for its present purpose.

It is of the 12th or 13th century, with a long handle and egg shaped

bowl. Its history is quite unknown.

See Cyril Davenport, The English Regalia, with illustrations in

colour of all the regalia; Leopold Wickham Legg, English Coronation

Records; The Ancestor, Nos. 1 and 2 (1902); Menin, The Form,

&c., of Coronations (translated from French, 1727).

REGENERATION OF LOST PARTS. A loss and renewal

of living material, either continual or periodical, is a familiar

occurrence in the tissues of higher animals. The surface of

the human skin, the inner lining of the mouth and respiratory

organs, the blood corpuscles, the ends of the nails, and many

other portions of tissues are continuously being destroyed and

replaced. The hair of many mammals, the feathers of birds,

the epidermis of reptiles, and the antlers of stags are shed and

replaced periodically. In these normal cases the regeneration

depends on the existence of special formative layers or groups

of cells, and must be regarded in each case as a special adaptation, with individual limitations and peculiarities, rather than

as a mere exhibition of the fundamental power of growth and

reproduction displayed by living substance. Many tissues,

even in the highest animals, are capable of replacing an abnormal

loss of substance. Thus in mammals, portions of

muscular tissue, of epithelium, of bone, and of nerve, after

accidental destruction or removal, may be renewed. The

characteristic feature of such cases appears to be, in the higher

animals at any rate, that lost cells are replaced only from cells

of the same morphological order—epiblastic cells from the

epiblast, mesoblastic from the mesoblast, and so forth. It is

also becoming clear that, at least in the higher animals, regeneration

is in intimate relation with the central nervous system.

The process is in direct relation to the general power of growth

and reproduction possessed by protoplasm, and is regarded by

pathologists as the consequence of “removal of resistances to

growth.” It is much less common in the tissues of higher

plants, in which the adult cells have usually lost the power of

reproduction, and in which the regeneration of lost parts is

replaced by a very extended capacity for budding. Still,

more complicated reproductions of lost parts occur in many

cases, and are more difficult to understand.

In Amphibia the entire epidermis, together with the slime-glands

and the integument sense-organs, is regenerated by the epidermic

cells in the vicinity of the defect. The whole limb of a Salamander

or a Triton will grow again and again after amputation. Similar

renewal is either rarer or more difficult in the case of Siren and Proteus.

In frogs regeneration of amputated limbs does not usually

take place, but instances have been recorded. Chelonians, crocodiles

and snakes are unable to regenerate lost parts to any extent,

while lizards and geckoes possess the capacity in a high degree.

The capacity is absent almost completely in birds and mammals.

In coelenterates, worms, and tunicates the power is exhibited in a

very varying extent. In Hydra, Nais, and Lumbriculus, after

transverse section, each part may complete the whole animal.

In most worms the greater, and in particular the anterior part,

will grow a new posterior part, but the separated posterior portion

dies. In Hydra, sagittal and horizontal amputations result in the

completion of the separated parts. In worms such operations

result in death, which no doubt may be a mere consequence of the

more severe wound. Extremely interesting instances of regeneration

are what are called “Heteromorphoses,” where the removed

part is replaced by a dissimilar structure. The tail of a lizard,

grown after amputation, differs in structure from the normal tail:

the spinal cord is replaced by an epithelial tube which gives off no

nerves; the vertebrae are replaced by an unsegmented cartilaginous

tube; very frequently “super-regeneration” occurs, the

amputated limb or tail being replaced by double or multiple

new structures.

J. Loeb produced many heteromorphoses on lower animals.

He lopped off the polyp head and the pedal disc of a Tubularia,

and supported the lopped stem in an inverted position in the sand;

the original pedal end, now superior, gave rise to a new polyp head,

while the neck-end, on regeneration, formed a pedal disc. In

Cerianthus, a sea-anemone, and in Cione, an ascidian, regeneration

after his operations resulted in the formation of new mouth-openings

in abnormal places, surrounded by elaborate structures characteristic

of normal mouths. Other observers have recorded heteromorphoses

in Crustacea, where antennulae have been regenerated

in place of eyes. It appears that, in the same fashion as more

simply organized animals display a capacity for reproduction of

lost parts greater than that of higher animals, so embryos and

embryonic structures generally have a higher power of renewal

than that displayed by the corresponding adult organs or organisms.

Moreover, experimental work on the young stages of organisms has

revealed a very striking series of phenomena, similar to the heteromorphoses

in adult tissues, but more extended in range. H. Driesch,

O. Hertwig and others, by separating the segmentation spheres,

by destroying some of them, by compressing young embryos by

glass plates, and by many other means, have caused cells to develop

| Plate I.

|

|

Fig. 1.—Sr EDWARDS CROWN. The ancient crown was destroyed at the Commonwealth, and a model made for Charles II's coronation.

|

|

Fig. 2.—The Imperial State Crown, as worn by Queen Victoria. The Black Prince's ruby is in the centre. Modifications in the cap were made for the coronation of King Edward VII. and the smaller “Cuilinan” diamond substituted for the sapphire below the ruby.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 3.—Queen Alexandra's Coronation Crown, with the Koh-i-Noor in centre. |

|

Fig. 4.—The Coronet of the Prince of Wales.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5.—The Larger or King's Orb.

|

The illustrations on these plates are, except where otherwise stated, reproduced by permission from the unique collection of photographs in the possession of Sir Benjamin Stone, formerly M. P. for East Birmingham.

|

Fig. 6.—The Lesser or Queen's Orb.

|

|

|

|

| Plate II.

|

|

|

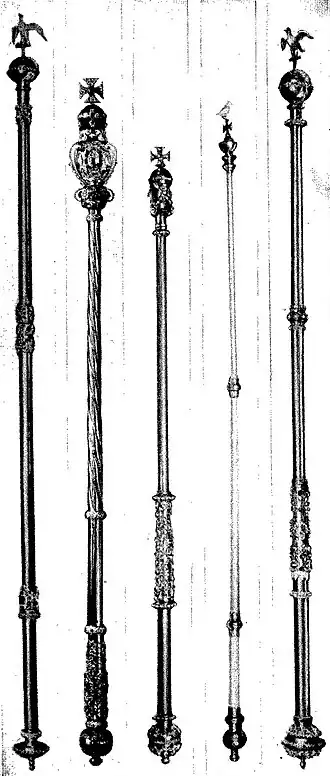

| Fig. 1.—The Sceptres: (a) The Scepter with the Dove; (b) The Royal Sceptre with the Cross (of Fig. 3); (c) The Queen's Sceptre with the Cross; (d) The Queen's Ivory Rod; (e) The Queen's Sceptre with the Dove.

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 6.—The Ampulla.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2.—The Coronation Spoon.

Fig. 3.—The Head of the Royal Sceptre with the largest of the “Star of Africa” (Cullinan) Diamonds.

|

|

Fig. 4.—The Swords: (a) The Spiritual Sword of Justice; (b) The Sword of State; (c) The Temporal Sword of Justice.

Fig. 5.—The Bracelets.

|

Fig. 7.—The Sr Georges Spurs.

|

|

|

| Plate III.

|

|

|

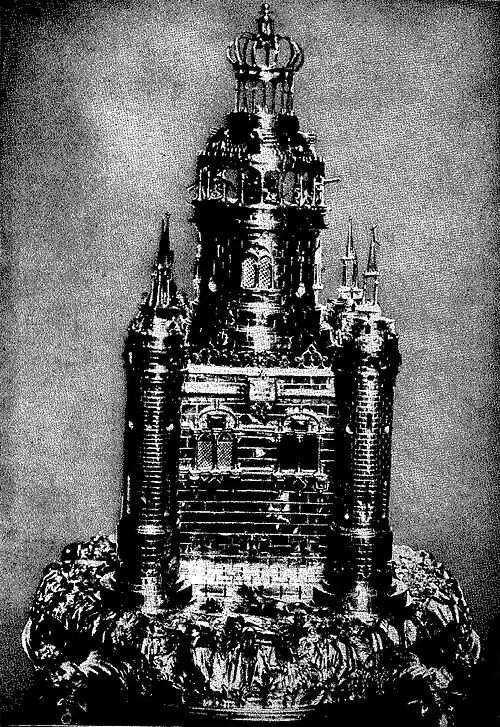

| Fig. 1.—The Silver-Gilt Christening Font, made for Charles II.

|

|

|

|

|

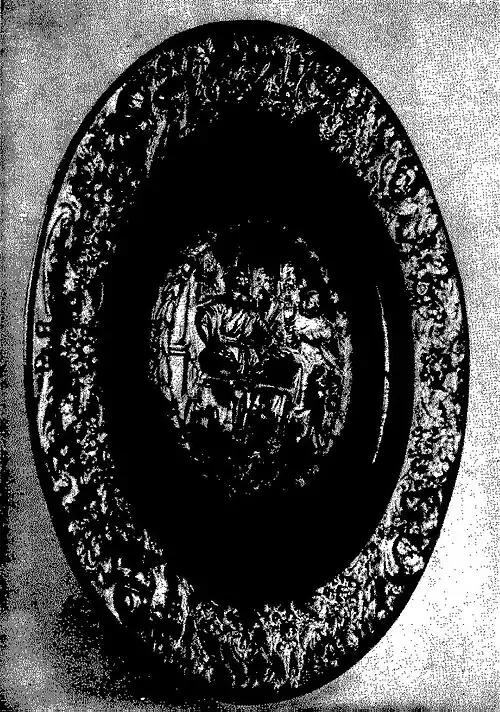

| Fig. 3.—Silver-Gilt Altar Dish, used at Christmas and Easter in the Chapel of Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London. |

|

|

|

|

|

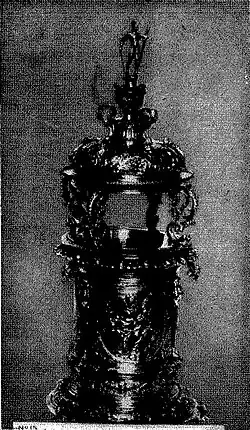

| Fig. 2.—Queen Elizabeth's Salt-Cellar.

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 4.—The Gold Salt-Cellar presented to the Crown by the City of Exeter.

|

|

|

|

| Plate IV.

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 1.—Silver-Gilt Altar Dish dated 1660, with representation of the Last Supper; it forms part of the Altar plate at the Coronation and is in the custody of the Chapels Royal. |

|

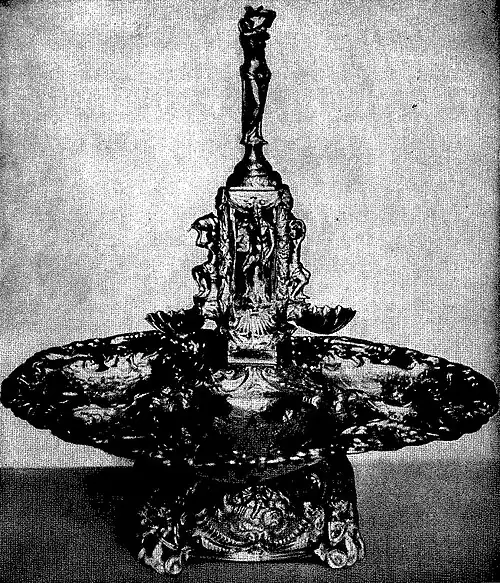

Fig. 2.—The Wine Fountain State Crown, presented to Charles II. by the Corporation of Plymouth.

|

|

|