Across Arctic America/Chapter 1

Across Arctic America

Chapter I

Old Friends in New Skins

I had halted to thaw my frozen cheeks when a sound and a sudden movement among the dogs made me start.

There could be no mistake as to the sound,—it was a shot. I glanced round along the way we had come, fancying for a moment that it might be the party behind signalling for assistance; but I saw them coming along in fine style. Then I turned to look ahead.

I had often imagined the first meeting with the Eskimos of the American Continent, and wondered what it would be like. With a calmness that surprised myself, I realized that it had come.

Three or four miles ahead a line of black objects stood out against the ice of the fjord. I got out my glass; it might, after all, be only a reef of rock. But the glass showed plainly: a whole line of sledges with their teams, halted to watch the traveller approaching from the South. One man detached himself from the party and came running across the ice in a direction that would bring him athwart my course. Evidently, they intended to stop me, whether I would or no. From time to time, a shot was fired by the party with the sledges.

Whether the shots fired and the messenger hurrying toward me with his harpoon were evidence or not of hostile intent, I did not stop to think. These were the men I had come so far to seek from Denmark and from my familiar haunts in Greenland. Without waiting for my companions to come up, I sprang to the sledge, and urged on the dogs, pointing out the runner as one would a quarry in the chase. The beasts made straight for him, tearing along at top speed. When we came up with him, their excitement increased; his clothes were of unfamiliar cut, the very smell of him was strange to them; and his antics in endeavoring to avoid their twelve gaping maws only made them worse.

"Stand still!" I cried; and, taking a flying leap out among the dogs, embraced the stranger after the Eskimo fashion. At this evidence of friendship the animals were quiet in a moment, and sneaked off shamefacedly behind the sledge.

I had yelled at the dogs in the language of the Greenland Eskimo. And, from the expression of the stranger's face, in a flash I realized that he had understood what I said.

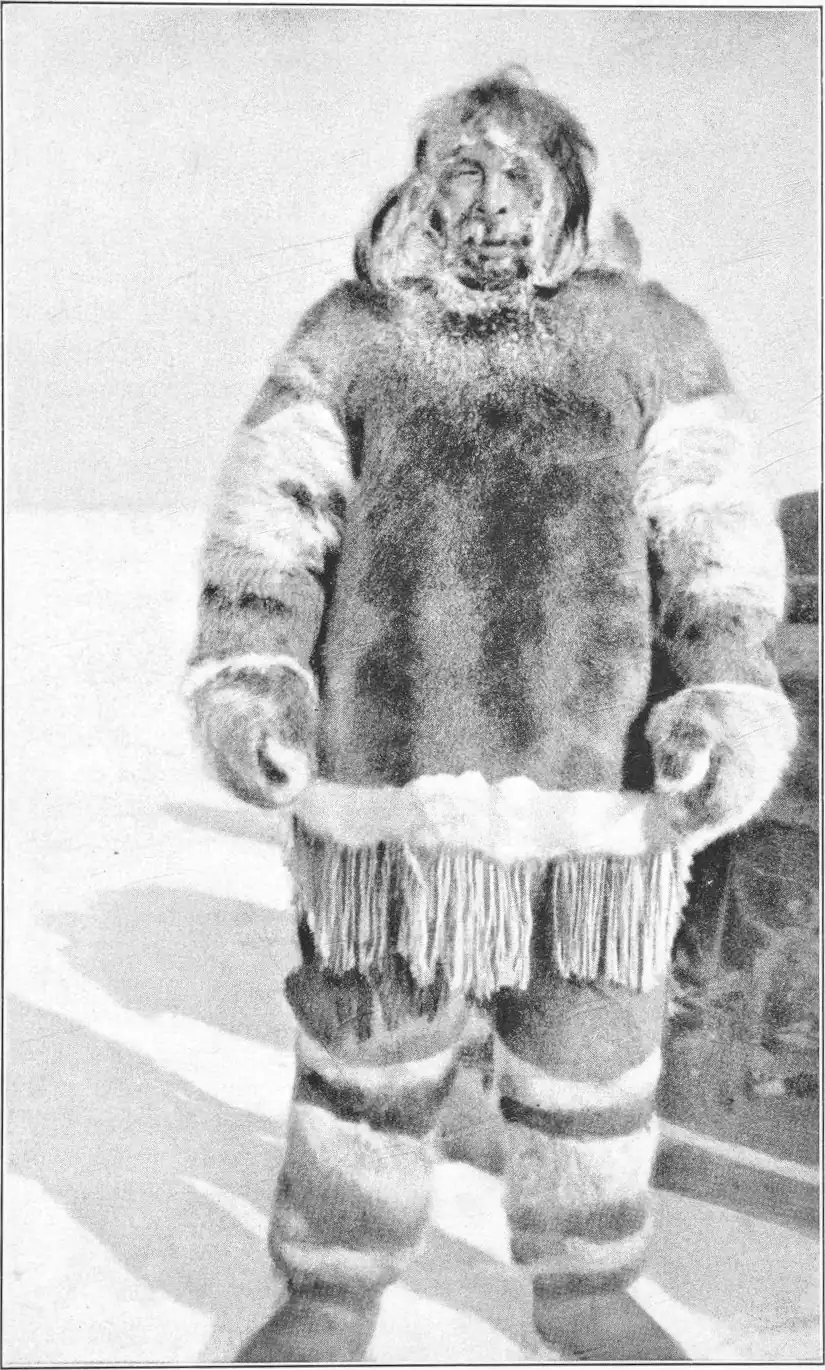

He was a tall, well-built fellow, with face and hair covered with rime, and large, gleaming white teeth showing, as he stood smiling and gasping, still breathless with exertion and excitement. It had all come about in a moment,—and here we were!

These men, then, were the Akilinermiut,—the "men from behind the Great Sea," of whom I had heard in my earliest youth in Greenland, when I first began to study the Eskimo legends. The meeting could hardly be more effectively staged; a whole caravan of them suddenly appearing out of the desert of ice, men, women and children, dressed up in their fantastic costumes, like living illustrations of the Greenland stories of the famous "inland-dwellers." They were clad throughout in caribou skin; the fine short haired animals shot in the early autumn. The women wore great fur hoods and long, flapping "coattails" falling down over the breeches back and front. The curious dress of the men was as if designed especially for running; cut short in front, but with a long tail out behind. All was so unlike the fashions I had previously met with that I felt myself transported to another age; an age of legends of the past, yet with abundant promise for the future, so far as my own task of comparing the various tribes of Eskimos was concerned. I was delighted to find that the difference in language was so slight that we had not the least difficulty in understanding one another. Indeed, they took us at first for tribesmen of kindred race from somewhere up in Baffin Island.

So far as I thought they would understand, I explained our purposes to my new friends. The white men, Peter Freuchen and myself, were part of a larger party who had come out of the white man's country to study all the tribes of the Eskimo,—how they lived, what language they talked, how they hunted, how they amused themselves, what things they feared, and believed about the future life—every manner of thing. We were going to buy and carry back to our own country souvenirs of the daily life of the Eskimo, in order that the white man might better understand, from these objects, the different way the people of the northern ice country had to live. And we were going to make maps and pictures of parts of this country in which no white man had ever been.

I introduced, then, my Eskimo companion (Bosun),—a man from Greenland who was almost as strange to the Akilinermiut as I. He had come along to hunt and to drive sledges, and do other work for the white man, while we gave our time to these studies.

My new friends were greatly pleased and impressed. They had just set out for their autumn camp up country at the back of Lyon Inlet, taking with them all their worldly goods. Being, however, like Eskimos generally, creatures of the moment, they at once abandoned the journey on meeting us, and we decided to set off all together for some big snowdrifts close at hand, where we could build snow huts and celebrate the meeting.

Accustomed as we were ourselves to making snow huts, we were astonished at the ease and rapidity with which these natives worked. The Cape York Eskimos, in Greenland, reckon two men to the task of erecting a hut; one cutting the blocks and handing them to the other, who builds them up. Here, however, it was a one-man job; the builder starts with a few cuts in the drift where he proposes to site his house, and then proceeds to slice out the blocks and lay them in place, all with a speed that left us staring open-mouthed. Meantime one of the women brought out a remarkable type of snow-shovel, with an extra handle on the blade, or business end, and strewed a layer of fine snow over the wall as it rose, thus caulking any chinks or crevices, and making all thoroughly weather-proof. Two technical points which particularly impressed our Cape York man, as an expert, were firstly the way these men managed to build with loose snow—some degree of firmness being generally considered essential—and further, the very slight arch of the roof, which has ordinarily to be domed pretty roundly for the blocks to hold, whereas here, it was almost flat. In less than three quarters of an hour, three large huts were ready for occupation; then, while the finishing touches were given to the interior, the blubber lamps were lighted and the whole made warm and cosy.

I and my two companions distributed ourselves among the three huts, so as to make the most of our new acquaintances. Caribou meat was put on to boil; but we found also, that our hosts had both tea and flour among their stores, which they had purchased from a white man down at Repulse Bay, not far from the camp. This was news of importance to us, for it meant we might have a chance of sending letters home in the spring.

In the course of the meal, I obtained some valuable information as to the neighborhood and neighbors. There were native villages, it appeared, in almost every direction round about our headquarters. They were not numerous, but the more interesting in their varied composition. There were the Igdlulik from Fury and Hecla Strait, the Aivilik between Repulse Bay and Lyon Inlet, and a party of Netsilik from the region of the North-west Passage. Only half a day's journey from the camp there was a family from Ponds Inlet, on the north coast of Baffin Land.

Conversation was for the most part general, as it mostly is on first acquaintance. Speaking the same tongue, however, we were not regarded altogether as strangers, and I was able even to touch on questions of religion. And I soon learned that these people, despite their tea and flour and incipient enamel-ware culture, were, as regards their view of life and habit of thought, still but little changed from their ancestors of ages past.

Plainly, here was work for us in plenty, and an interesting task it promised to be. We had, moreover, been well received, and I anticipated little difficulty in gathering information. First of all, however, we must go on to seek the nearest Hudson's Bay Company station, and find out whether there really would be any opportunity of postal communication in the spring.

We started accordingly, on the following morning. On the 5th of December, while it was still daylight, we reached the spot where, according to the Eskimo accounts, the white man had his quarters. At the base of a little creek, behind huge piles of twisted and tumbled ice, stood a modest looking building, dark against the colony of snow huts which surrounded it. This, we found, was the extreme advanced post of the Hudson's Bay Company of Adventurers, one of the oldest and greatest trading companies in the world.

We had hardly drawn up in front of the house before the station manager, Captain Cleveland, came out and greeted us with the most cordial welcome. He proved, also, to be a remarkably quick and efficient cook, and had a meal ready for us in no time; a steaming dish of juicy caribou steaks and a Californian bouquet of canned fruit in all varieties.

George Washington Cleveland was an old whaler who had been stranded on the coast here over a generation before, and made himself so comfortable among the Eskimos that he had never been able to. tear himself away. Nevertheless, he was more of an American than one would expect from his isolated life, and was proud of having been born on the very shore where the Mayflower had first landed. He had been through all manner of adventures, but neither shipwreck nor starvation, not to speak of the other forms of adversity that had fallen to his lot, could sour his cheery temper or impair his steady, seaman-like assurance of manner.

We knew really very little about this arctic region of Canada, and Captain Cleveland's information was most valuable to us later on. We learned now that one of the Hudson's Bay Company's schooners, commanded by a French Canadian, Captain Jean Berthie, was wintering at Wager Bay, five days' journey farther to the south. There was a chance that we might be able to send letters home in the course of the winter by this route, and it was at once decided that Freuchen should set out for the spot and bring back news.

There was a dance that evening, to celebrate the visitors' arrival. The Eskimo men and women had learned, from the whalers, American country dances. Music was provided by the inevitable gramophone which seems to follow on the heels of the white man to most parts of the world. And the women were decked out in ball dresses hastily contrived for the occasion from material supplied by Captain Cleveland.

Later on, we made a round of the huts, which were refreshingly cool after the heat of the ballroom. We were anxious to get more information as to the country round, but being unacquainted with the Eskimo names of places near, we could only go by the old English maps, and were rather at a deadlock when aid arrived from an unexpected quarter. An old fellow with a long white beard, and eyes reddened with the strain of many a blizzard, revealed himself as a geographical expert.

We brought out paper and pencil, and to my astonishment, this "savage" drew, without hesitation, a map of the coastline for a distance of some hundreds of miles, from Repulse Bay right up to Baffin Land. The map completed, he told me all the Eskimo place names, and at last we are able to get a real idea as to the population of the district and the position of the settlements. I was elated here to note that the majority of these names; Naujarmiut, Pitorqermiut, Nagssugtormiut and many others, were identical with some of the familiar place names from that part of Greenland where I was born. And when I began telling of the Greenland folk tales to the company here, it turned out that they knew them already; and were, moreover, themselves astonished to find that a stranger should be acquainted with what they regarded as their own particular legends.

I was looking forward to closer acquaintance with these people and their history and traditions; Ivaluartjuk, who had drawn the map, would, I foresaw, be particularly useful as a source of information. But we could not now remain longer than the one whole day, and on the 7th of December, we took leave of our new friends, Freuchen going down as arranged to meet Captain Berthie at Wager Bay, while Bosun and I drove back to our winter quarters. After passing Haviland Bay, however, we came upon some old sledge tracks, and decided to follow and see whither they led.