Across Arctic America/Chapter 10

Chapter X

"I Have Been So Happy!"

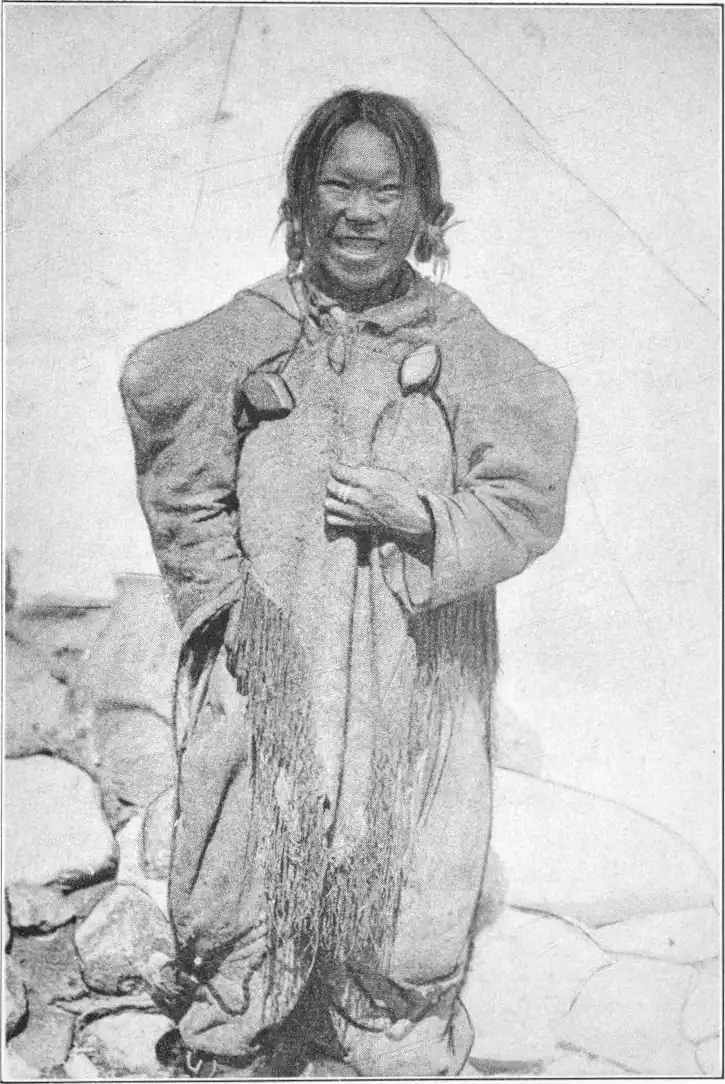

Aua's wife Orulo was one of those women who give themselves up entirely to their housewifely duties. She was never idle for a moment from morning to night and could get through a wonderful amount of work. Her favorite occupation was sewing, and of this there was plenty, as the men's clothes were constantly in need of repair after the wear and tear of hunting. But she had many other things to attend to besides. It was her business to fetch in snow for water, and keep the hut supplied, to have a stock of meat thawing near the lamp for immediate use, and a supply of food for the dogs ready cut up when the men came home. There was blubber to be pressed and beaten that the oil might run out, the lamp itself to be tended carefully and kept from smoking. If the temperature inside the hut rose beyond a certain point, the roof would begin to drip, and had to be plastered with fresh snow from within. Occasionally, when a part of the roof or wall thawed through, she had to go out and cut away the weakened portion, fitting fresh blocks of snow into the hole. There was blubber to be scraped from the raw skins of newly killed seal, the skins themselves stretched out to dry on the frame above the lamp, and pieces of hide intended for boot soles had to be chewed from their original state, which was almost as hard as wood, until they were soft enough for working. All these manifold duties however, she took cheerfully as part of the day's work, and went about humming a scrap of some old song, as happily as could be. And there was sure to be a cheerily bubbling pot on the boil—more welcome music still—by the time her menfolk came in from their hunting.

With it all she found time to look in and see that all was well with her neighbors, lending a helpful hand where needed, and finding a bit of meat, or a lump of blubber, from her own store for those who were badly off.

I had often asked her to tell me something of her life, and such of her experiences as she reckoned the most important, but she always turned it off as a joke, declaring that there was nothing of the least importance to tell about. At last one day when we had the hut to ourselves, she returned to the subject of her own accord. I was busy with my own work, and hardly conscious of her presence, when she began without preamble. And there, sitting cross-legged on the skins, working the while at a pair of waterproof boots, she told me the story of her life.

"I was born at a place near the mouth of Admiralty Inlet, but while I was still quite small, my parents left Baffin Land and came to Idglulik. The first thing I can remember was that my mother lived alone in a little snow hut. I could not understand why my father lived in another, but then I was told that it was because my mother had just had a child, and must not be near the hunters. But I was allowed to visit her myself; only when I went there first, I could not find the entrance. I was so little at that time that I could not see over the big block of snow that the others stepped over when they went in, and there I stood crying out 'Mother, Mother, I want to come in, I want to come in.' At last someone came out and lifted me over and into the hut. Then when I got inside it seemed that the couch of snow she was lying on was ever so high, that I could not get up there by myself, and again someone had to lift me. Yes, I was as little as that at the time when I first can remember.

"The next thing I remember is from the time we were at Piling, up in Baffin Land. I remember having the leg of a bird to eat, ever so big it was, but that was because I was only used to having ptarmigan, and this was the leg of a goose. I remember thinking what a huge big bird it must be.

"Then I cannot remember any more until one day it seems to wake up again, and we were living at a place called the Mountain. My father was ill, and all the others had gone away hunting caribou and we were left alone. My father had pains in his chest and lungs, and grew worse and worse. And there we were all alone, my mother and two little brothers and myself, and mother was very unhappy.

"One day I came running into the tent crying out: 'Here are white men coming!' For I had seen some figures that I thought must be white men. But when my father heard me, he sighed deeply and said, 'Alas, I had thought I might yet be suffered to draw the breath of life a little while; but now I know that I shall never go out hunting any more.'

"For the figures I had seen were evil trolls; no white men ever came to our country in those days. And my father took it as a warning that he was about to die.

"I made no secret of what I had seen, but told it to the others without thinking either way about the matter. But my little brother Sequsu kept it secret; and he died of it shortly afterwards. When one sees evil spirits, it is a great mistake to keep it secret.

"Father grew worse and worse, and when at last we saw he could not live much longer, we put him on a sledge and carried him off to a neighboring village, where he died. I remember they wrapped him up in a skin and carried him away; the body was laid out on the bare ground, with its face toward the west. My mother told me that this was because he was an old man; when old men die, they are always placed so as to look toward the quarter whence the dark of evening comes; children must look towards the morning, and young people towards the point where the sun is at noon. This was the first I ever learned about the dead, and how we have to fear them and follow certain rules. But I was not afraid of my father, who had always been kind to me. And I thought it was unkind to let him lie there out in the open, all in the cold with no covering; but then my mother explained that I must no longer think of him as in

"After this we went to live with an old man who took my mother to be another wife to him, and we lived in his hut. It was soon after this that my brother Sequsu fell ill; he had pain in his stomach, and his liver swelled, and then he died. I was told that it was because he had seen those evil trolls with me before our father died, and because he had kept it secret, it had been his death, for it is always so.

"In the autumn, when the first snow had fallen, the others went off hunting up inland, and my other brother went with them. I remember my mother was very anxious about this, for she did not think the old man could get any game, having only a bow and arrows. But she could not get food for herself, and so had to let my brother go with them.

"A strange thing happened a little after this. My mother had cooked some walrus ribs and was sitting eating, when the bone she had in her hand began to utter sounds. She was so frightened she stopped eating at once and threw down the bone. I remember her face went quite white, and she cried out: 'Something has happened to my son!' And so it was; for in a little while they came back and instead of walking straight into the hut, the man went to the window and called to my mother and said: 'Dear Little Thing, it is through my fault that you have no longer a son.' Dear Little Thing was a name he had for my mother. And then he came in and told us how it had come about. They had been for several days without food and were seeking the spot where he had cached a caribou some time before, but could not find the spot. So they separated, his wife going one way and he with the two boys the other. But still they could not find it. It was autumn, the first snow had fallen, and a cold wind sent it whirling about them every now and then; and their clothes were poor for such hard weather. So at last they lay down behind a stone shelter, worn out and almost perishing with cold. The days were short now and the night seemed very long, but they must wait for daylight before they could begin their search again. Meantime, the woman had found the meat, but now she had no means of knowing where to find the others. Being anxious about them she ate but little herself, and gave the child she was carrying a tiny piece of meat to suck. She had made a shelter of stones, as the others had done, and lay there half dozing, when suddenly she awoke, having dreamed of my brother. The dream was that she saw him quite plainly before her, very pale and shivering with cold. And he spoke to her and said: 'Now you will never see me again. This has come upon us because the earth-lice are angry at our having touched their sinews before a year had passed after my father's death.'

"I remember this so distinctly myself, because it was the first time I ever heard about not doing certain things for a year after someone had died. When he said earth-lice, he meant caribou; that is a word the wizards use.

"Now the woman could sleep no more that night because of her dream. My brother was very dear to her, and she used to say magic words over him to make him strong.

"Next morning, when it was light and the others were ready to start again, my brother was so weak that he could not stand, and the two others were too exhausted to carry him. So they covered him up with a thin caribou pelt and left him. Afterwards they found the meat, but they did not return to my brother. He was left to freeze to death.

"My stepfather had his old mother still living; she was blind, and I remember I was terribly afraid of her because I had heard that once, in a time of famine, she had eaten human flesh. A wise woman had said charms over her to cure her blindness, and she had just begun to see a very little, but then she ate some blubber, and that is a thing one must never do when being cured of anything by magic; after that she became quite blind again and nothing could make her see.

"The following spring we left that place and came to Admiralty Inlet. We got there just at the time when everyone was getting ready to go up country hunting caribou. One of the women had just given birth to a child before her time, and could not go with the rest, so my mother went instead, and took me with her. We stayed up country all that summer. The hunting was good, and we helped the men to pile up the meat in store places or cut it up into thin slices and laid it out on stones to dry. It was a merry life, we had all kinds of nice things to eat, and the day's work was like so much play. Then I remember one day we were terrified by a woman from one of the tents crying out: 'Come and look, Oh come and look.' And we all ran up and there was a spider letting itself down to the ground. We could not make out where it came from, it looked as if it were lowering itself on a thread from the sky. We all saw it quite plainly, and then there was silence among the tents. For when a spider is seen to lower itself down from nowhere in that way, it always means death. And so it was. Some people came up from the coast shortly after, and we learned that four men had been out in their kayaks and were drowned; one of them was my step-father—and now we were homeless and all alone in the world once more.

"But it was not long before my mother was married again; this time to a young man, much younger than herself. They lived together until he took another wife of his own age; then my mother was cast off and we were alone again. Then my mother was married once more, to a man named Aupila, and now we had some one to look after us. Aupila wanted to go down to Pond's Inlet, to look for some white men. He had heard that the whalers generally came to that place in the summer. So he went off with my mother, and I was left behind with another man and his wife. But I did not stay with them long, for the man said he had too many mouths to feed already, and I was passed on to someone else. Then at last Aua came and found me; 'my new husband' that is my little name for Aua; and he took me away and that is the end. For nothing happens when you are happy, and indeed I have been happy, and had seven children."

Orulo was silent, evidently deep in thought. But I was eager to hear more, and broke in without ceremony:

"Tell me what is the worst thing that ever happened to you."

Without a moment's hesitation she answered:

"The worst that ever happened to me was a famine that came just after my eldest son was born. The hunting had failed us, and to make matters worse, the wolverines had plundered all our depots of caribou meat. During the two coldest months of winter, Aua hardly slept a single night in the hut, but was out hunting seal the whole time, taking such sleep as he could get at odd moments in little shelters built on the ice by the breathing holes. We nearly starved to death; for he only got two seal the whole of that time. To see him, suffering himself from cold and hunger, out day after day in the bitterest weather, and all in vain, to see him growing thinner and weaker all the time—oh, it was terrible!"

"And what was the nicest thing of all you remember?"

Orulo's kindly old face lit up with a merry smile; she put down her work and shifting a little nearer began her story:

"It was the first time I went back to Baffin Land after I was married. And I, who had always been poor, a child without a father, passed on from hand to hand—I found myself now a welcome guest, made much of by all those who had known me before. My husband had come up to challenge a man he knew to a song contest, and there were great feasts and gatherings, such as I had heard of perhaps but never seen myself."

"Tell me something about them."

"Well there was the Tivajuk, the Great Rejoicing, where they play the game of changing wives. A big snow hut is built all empty inside, just for the dancing, only with two blocks of snow in the middle of the floor. One is about half the height of a man and is called the jumping block, the other is a full man's height and is called the lamp block. Two men, they are the Servants of Joy, are dressed up, one like a man, the other like a woman, and both wear masks. Their clothes are made too small for them on purpose, tied in tightly just where they ought to be loose, and that makes them look funny, of course. It is part of their business to make everyone laugh.

"Then all the men and women in the place assemble in the dance hut, and wait for the two masked dancers. Suddenly the two of them come leaping in, the man with a dog whip and the one dressed as a woman with a stick; they jump over the jumping block and begin striking out at all the men in the hut, chasing them all out until only the women are left. The maskers are supposed to be dumb, they do not speak, but make signs to each other with great gestures only giving a sort of huge gasp now and again with all the force of their lungs. They have to leap nimbly about among the women, to make sure there are no men hidden; then out they go to the men waiting outside. One of the men waiting now goes up to the two, and smiles, and whispers the name of the woman he specially wants. At once the two maskers rush into the hut, and touch the woman named under the sole of the foot. Then all the other women are supposed to be ever so pleased to find that one of their number has been chosen. Then the three go out together; and every time the maskers go in and out they have to jump over the jumping block with long strides trying to look funny. They lead out the woman who has been chosen, and bring her back directly after with the man who asked for her; the women are never allowed to know who it is that wants them till they get outside. Both have to look very solemn when they come in, and pretend not to notice that the others are laughing. If they laugh themselves, it means a short life. All the others then call out 'Unu-nu-nu-nu-nu-nu' and keep on saying it all the time, in different voices, to make it sound funny. Then the man leads the women he has chosen twice round the lamp block, and all sing together:

"While this song is being sung, the two maskers have to keep on embracing each other, making it as funny as they can, so that the others have to laugh.

"So the game goes on until every man has chosen a woman, and then they go home.

"Another festival that is only held where there are a lot of people together is called Qulungertut. It begins with two men challenging each other to all kinds of contest out in the open, and ends up in the dance house.

"Each of them has a knife, and as soon as they meet, they embrace, and kiss each other. Then the women are divided into two parties. One side sings a song and they have to keep on with it all the time, a long, long song; the other side has to stand with arms up waving gull's wings all the time and see who can keep on longer. Here is a bit of the song:

"The side that first gives in has to step across to the others, who make a circle round them, and then the men come in and try to kiss them.

"After this game there was a shooting match with bow and arrows. A mark was set up on a long pole, and the ones who first hit it ten times were counted the best. Then came games of ball, and very exciting contests between men fighting with fists, until the end of the day, and then a song festival to end up with, and that lasted all night. Here are some of Aua's songs:

Walrus Hunting

Bear Hunting

Caribou Hunting

Orulo had spoken earnestly of her life, and I could feel, as she went on, how the memories affected her while she recalled them. When she had ended her story, she burst into tears, as if in deep sorrow. I asked her what was the matter, and she answered:

"Today I have been as it were a child again. In telling you of my life, I seemed to live it all over again. And I saw and felt it all just as when it was really happening. There are so many things we never think of until one day the memory awakens. And now you have heard the story of an old woman's life from its first beginning right up to this very day. And I could not help weeping for joy to think I had been so happy …"