Across Arctic America/Chapter 11

Chapter XI

Separate Ways

The prolonged absence of Therkel Mathiassen at Southampton caused us, at last, so much uneasiness that I began making preparations for a relief expedition, and even sent down to Repulse Bay for a guide, thoroughly acquainted with the region, to go with me.

February 21st was a perfect beast of a day, with a howling blizzard, and bitterly cold. Nobody stirred out of the house if he could help it. The Greenland Eskimos were indoors mending harness, the rest of us posting up our journals. Then, suddenly, the door burst open, and in tumbled Therkel Mathiassen, with Jacob Olsen at his heels, followed by John Ell, and a crowd of Southampton Islanders.

Mathiassen had been eight months absent. We gave him a rousing welcome, as may be imagined.

The expedition had done good work and met with not a few adventures by the way. Southampton Island is the most isolated piece of territory in the whole Hudson Bay district, and accessible by open boat for only a few days during the summer. They had planned to spend only a fortnight there, but unfavorable weather and other mishaps detained them. The local natives couldn't do anything for them, and when Mathiassen violated tabus by cracking caribou skulls with iron hammers, he

For we had now come to the parting of the ways, and the Fifth Thule Expedition was about to split up into five separate projects each with its own field of work, scattering over the greater part of the Arctic Coast of Canada.

Mathiassen was to go by dog-sledge to Pond's Inlet in Baffin Land, to supplement his ethnological investigations with map-making and other studies in that territory.

Birket-Smith with Jacob Olsen as interpreter, was to continue with the Caribou Eskimos, and then go on to the Chipywan Indians, near Churchill.

Peter Freuchen was to stay for a while to look after the transportations of our collections, and then survey the route to Chesterfield. The Greenlanders would remain at headquarters, until they could be taken back to Greenland by Freuchen.

And I, myself, was to start, about the 10th of March, for my long sledge trip through the Northwest Passage, with only Miteq and Anarulunguaq to help me. Helge Bangsted would accompany me a little way, and then, after further excavations, would return to help Freuchen supervise the removal of our effects.

The rest of this account will have to do only with my own observations, but I carried with me for some time the regret of breaking off contact with companions with whom I had been so happily associated for eighteen months. And it is a pleasure to recall that our work together was never marred by the slightest discord among ourselves.

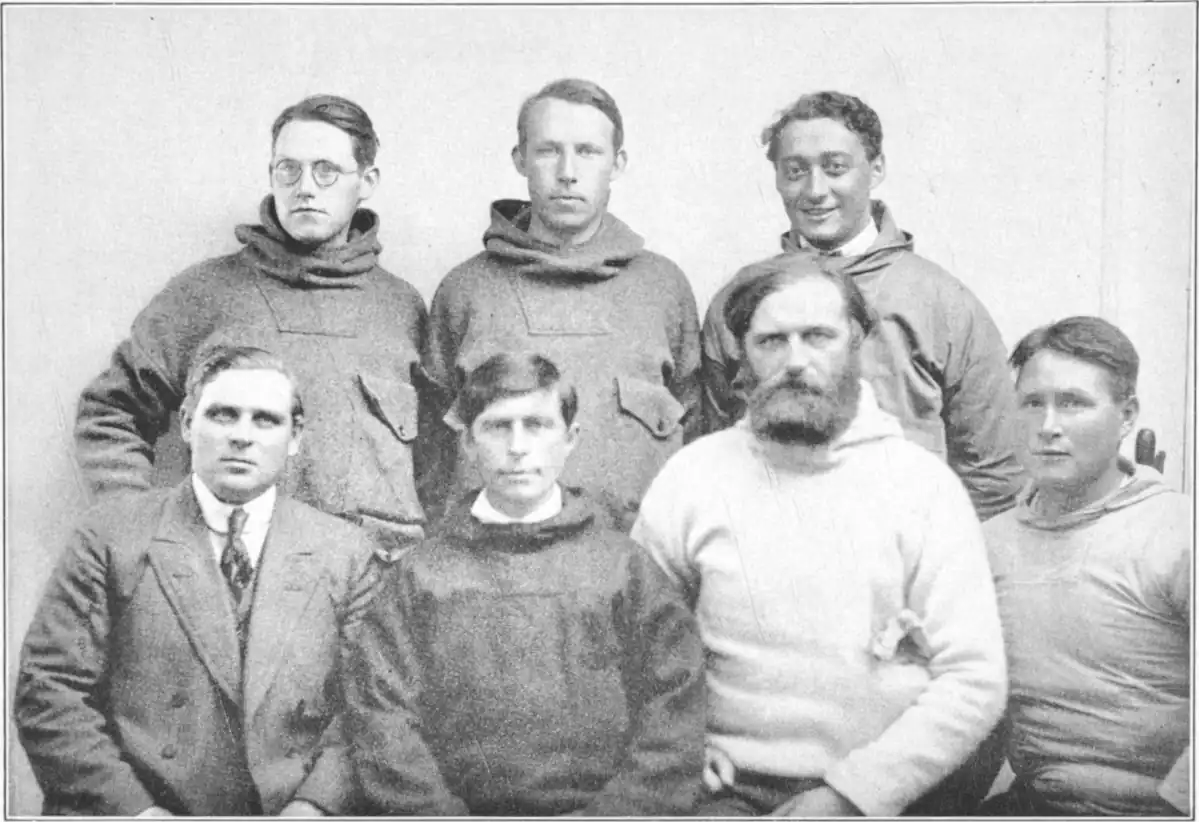

The Greenlanders, too, had done their part well. Like all other Arctic expeditions we had based our maintenance on the help afforded by these faithful hunters and workers. There was Arqioq, a steady sensible fellow of thirty odd, who had spent most of his life with one expedition or another, including two from America. Bosun, a few years younger, had been my foster son at Thule since he was ten years old. He was a dead shot, a good comrade, and cheerful under the most adverse circumstances. Their wives, too, had done all that was possible to make our headquarters homelike and comfortable.

Especial gratitude was due to Jacob Olsen, not only for his indispensable services to Mathiassen, but also for his abilities. In contrast with the others, who had lived always native fashion, and were only baptized just before we left Greenland, Olsen was a man of some education, having spent six years in a seminary and acquired a considerable knowledge of books, though he was no less adequate as a hunter on that account. He was valued as an interpreter, and was useful even in collecting ethnographical material.

I should like to close this part of the book with a recollection of one of our last evenings at home. I had just come in from a run over the ice, and was driving up in the twilight towards the house, where the light from the windows shed a glow on the space in front. Some of the dogs were sleeping, as if making the most of their time before fresh hard work set in; groups of men and women were at work by lantern light getting the new sledges ready for use. The daylight was not long enough for all there was to be done. Hammers rang, and the rhythmic back-and-forth of the plane spoke cheerily of work well in hand. A wild scene, maybe, yet not without a beauty of its own. Dark against the white plain rose the two peaks where we had raised memorial stones to those whom death had taken on the threshold; at the foot, stood the domed snow huts, with little ice windows twinkling like stars.

Into the midst of this I drove, my team scattering their sleeping companions to every side and bringing up against the wall where they were accustomed to lie themselves. And as we halted, I heard someone singing a little way off. The words seemed curiously appropriate to the occasion: