Across Arctic America/Chapter 12

Chapter XII

Stepping Out

The Arctic spring was full of promise on that March morning when we took leave of our companions and set out on our long sledge trip. Two continents lay between us and home.

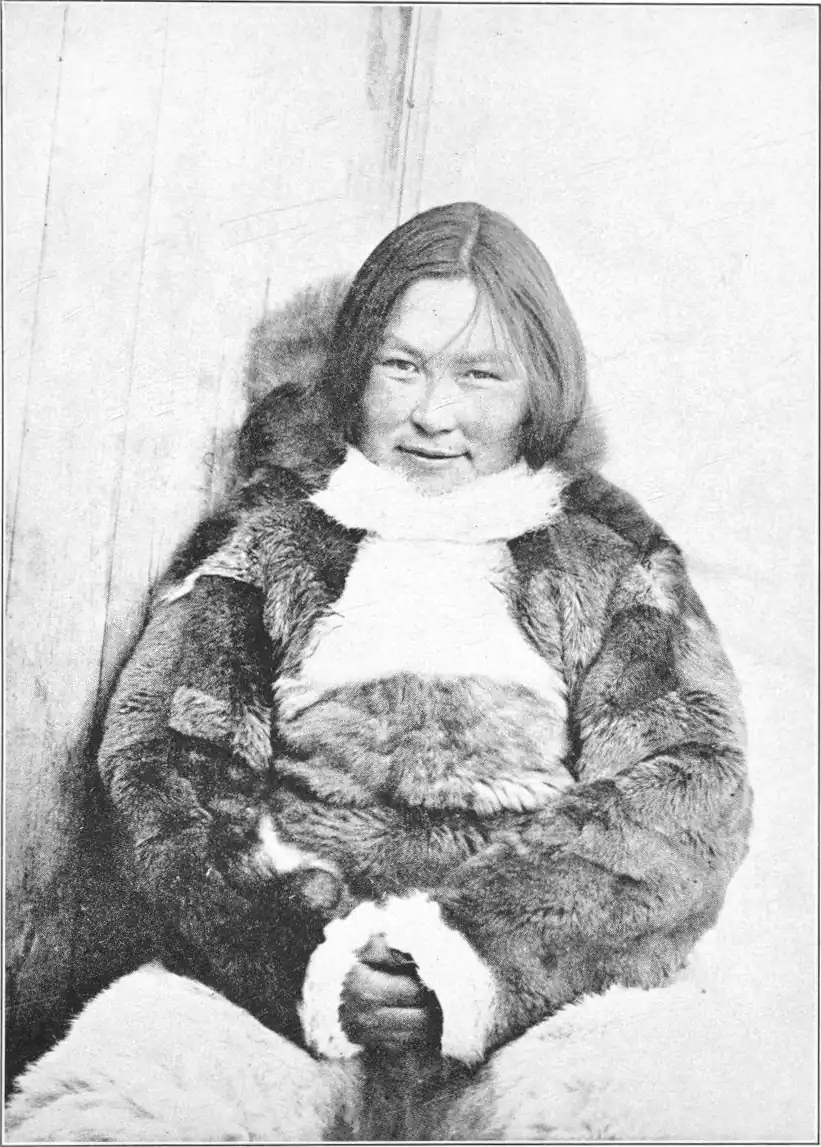

Our party consisted of but three persons in all; Miteq, Anarulunguaq and myself. Miteq, a young man of twenty-two from Thule was a very old friend of mine; I had known him, indeed, from the time when he lay screaming lustily in his mother's amaut. He was a skilful and untiring hunter, and a good driver, besides being a cheery companion. Anarulunguaq, a woman of twenty-eight, was Miteq's cousin. Oddly enough, she had as a child been on the point of being killed off as a burden to the community, as is often done with fatherless children, but her little brother's intercession had saved her life. And here she was setting out upon a journey that was to make her the most famous woman traveller of her tribe. I could not have wished for better companions than these two.

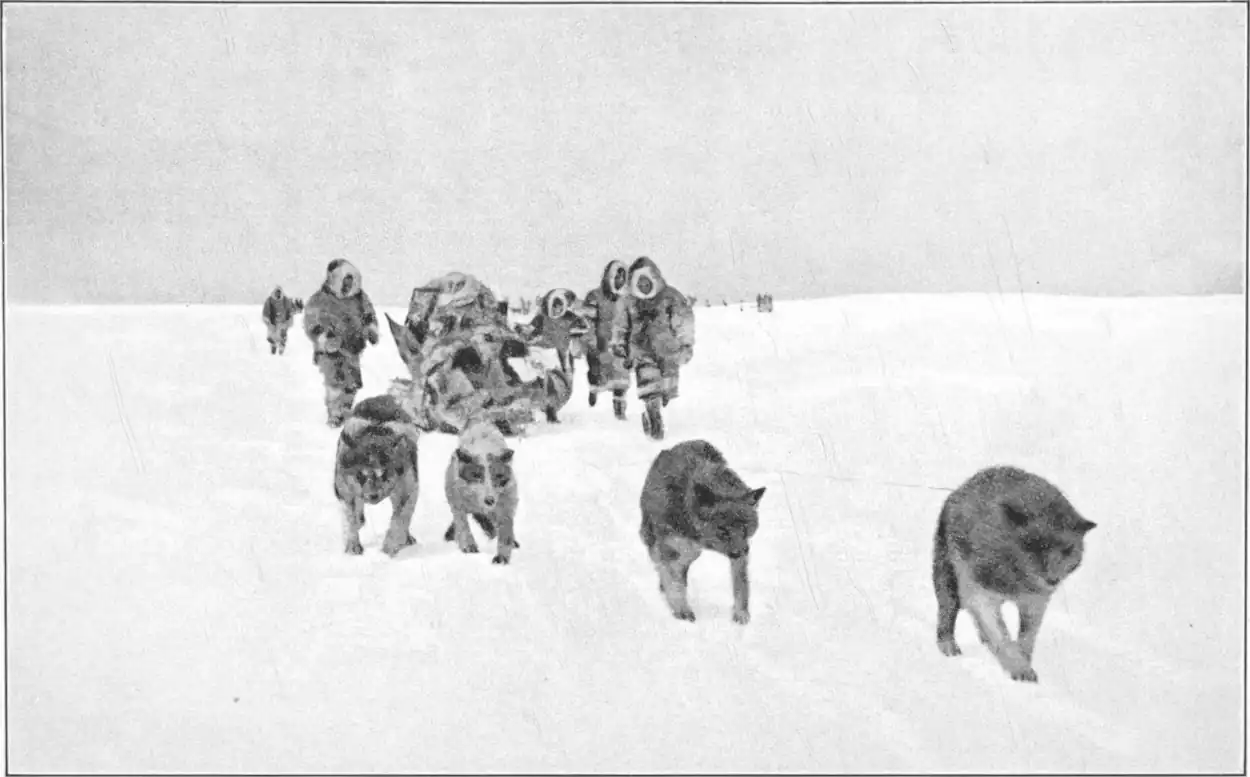

Our equipment was the simplest possible. We had two long six-metre sledges of the Hudson Bay type, with ice shoeing, each drawn by twelve dogs, and with a load of 500 kilos. to each sledge. About

And now we were fairly off, our last link with civilization severed. There was no means of communication now until we reached a telegraph station somewhere in Alaska. All we had to look to for our lives was on our sledges, and they seemed none too heavy as we set off at a sharp trot along the North Pole River.

We crossed Rae Isthmus by short stages, and had then the lowlands of Simpson Peninsula between us and Pelly Bay. Before we could begin the crossing of this, however, we had to cover some distance along the ice foot on the shore of Committee Bay, the sea ice being too rough for our heavy loads. The incessant wind had carried away most of the snow from the plain, and clay and pebbles showed through everywhere; we had therefore to take the ice shoeing off the runners of one sledge in order to get the loads down to the ice foot.

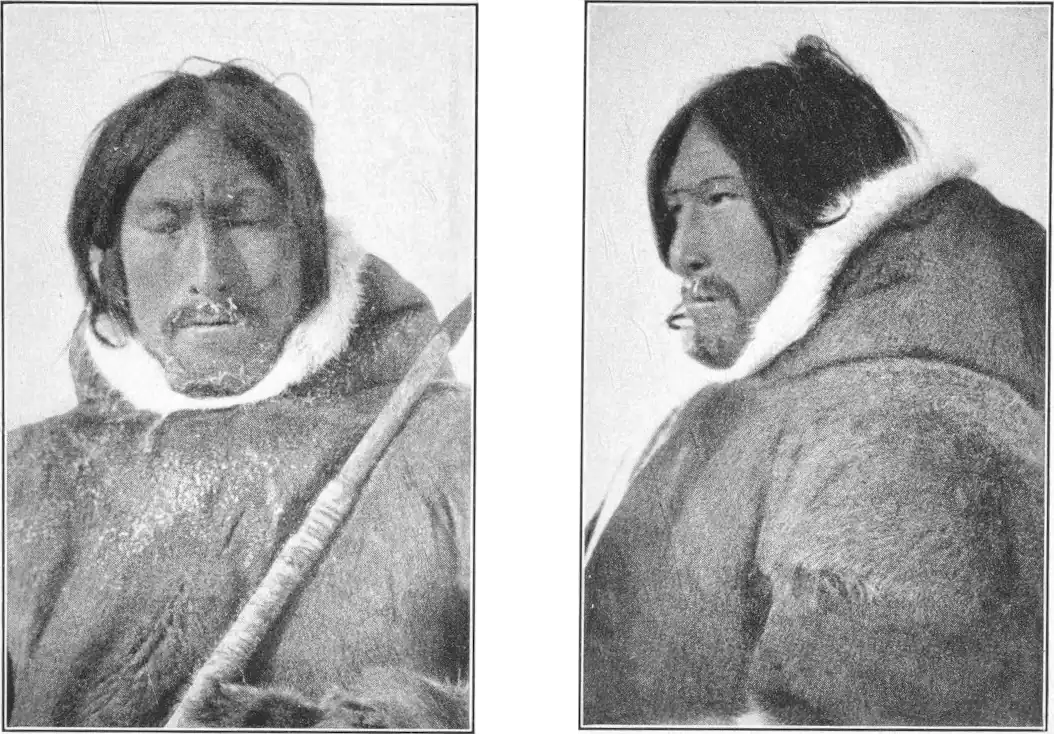

On the 28th of March, in a tearing blizzard, we had our first meeting with the natives of these parts. We had built a snow hut, and were just deciding it was no use going on for the present, when Miteq, who had gone outside for snow to repair the wall, called in through the opening that there were men approaching.

And sure enough, two tall figures could be seen coming towards the hut. At about 300 metres distance they stopped, and I at once went forward to meet them and assure them we were friends. They carried long snow knives and sealing harpoons, but I thought it best to carry no weapon myself. They were greatly astonished to find a white man in these regions, and more so when I hailed them in their own tongue:

"You may lay aside your weapons; we are peaceable folk who have come from afar to visit your land."

On this the elder of the pair stepped forward and said:

"We are just quite ordinary people, and you need fear no harm from us. Our huts are near; our weapons are not meant to do you hurt, but it is well to have weapons here when meeting strangers."

We went back to our hut, and the two men, who had been somewhat shy at first, were soon at ease and friendly. They were particularly interested in the two Greenlanders, who came from so far a country and yet spoke the same tongue. They themselves, it appeared, were on their way down to Repulse Bay with fox skins, to buy new guns, their own having been lost in crossing a river some time before.

Despite the blizzard, we now decided to move over to our new friends' quarters. Orpingalik, the elder of the two, explained that they were but a short distance away. It cost us three hours fierce battling with the storm, however, before we reached the spot. There were two snow huts built together, cosy, well furnished and well supplied with food. The natives here were remarkably well built and handsome, differing in many ways from the ordinary

Orpingalik was an angakoq, and well up in the legends and traditions of his people, and I was glad to avail myself of the time while my companions were busy getting our goods down, to have a talk with him about such matters. I was anxious in the first place to learn how many of the stories I had already written down among the Igdlulingmiut were known to him, and we went through at least a hundred of these together. Also, he gave me some rare magic songs, or spells, which I paid for in kind, giving him in return some of those I had obtained from Aua. The transaction was regarded as perfectly legitimate, as the magic would take no harm when it was a white man who acted as the medium of conveyance.

These magic songs and spells are difficult to translate, as the words themselves are often meaningless in the actual context; they have to be uttered in a peculiar way, with great distinctness and sometimes with pauses here and there; the virtue lies to a great extent in the way they are spoken.

One which Orpingalik regarded as of great value was the Hunter's Invocation, which is roughly as follows:

When he had given me this, he declared that we were now almost like brothers. Another useful song is the Poor Man's Prayer to the spirits, which is spoken at dawn before setting out hunting, when the blubber is running low and fresh supplies are urgently wanted.

This is used for seal; when hunting caribou, on the other hand, one must say:

Orpingalik himself was a poet, with a fertile imagination and sensitive mind; he was always singing when not otherwise employed, and called his songs his "comrades in loneliness." Here is the beginning of one of them—written when he was slowly recovering from a severe illness. It is called My Breath.

I asked Orpingalik how many songs he had made up, and he said "I cannot tell you, for I do not know how many there are of these songs of mine. Only I know that they are many, and that all in me is song. I sing as I draw breath."

Singing is indeed very prevalent among these people. They go about singing all day, or humming to themselves. The women sing not only their husbands' songs, but have songs of their own as well. Orpingalik taught me one that belonged to his wife. They had a son, Igsivalitaq, who had killed a man some years before, and was now living as an outlaw up in the hills near Pelly Bay, in fear of being brought to justice by the Mounted Police. His mother had made a song about him, as follows:

The song is interesting less for its form than for the evidence it affords as to the workings of the primitive mind.

On the 5th of April we took leave of Orpingalik and his people, the whole party shouting after us as we drove off:

"Tamavta tornaqarata ingerdlasa" ("May we all travel with no evil spirits in our train").

We had bought a store of meat from Orpingalik before leaving, and were to pick it up on the way from the spot where it was cached. Part was fish, the rest seal meat and caribou. The fish we found without much difficulty, and were delighted to find that we had purchased, for a pound of tea, a pound of sugar, twenty cakes of tobacco and a small pocketknife, something like six hundred pounds of fine sea trout, besides the seal and caribou. To get at this last, however, we had first to hunt up Igsivalitaq the outlaw, who knew where it was. This was rather a delicate task, and Orpingalik had warned us to be careful how we approached him. We found his hut, but it was empty, and fresh tracks showed that he and his party had made off to the northward. Following up the tracks, we came up with him in the course of the day. I greeted him with the same words as his father had used at our first meeting:

"We are just quite ordinary people, and you need fear no harm from us."

The outlaw was evidently relieved to find that he was not being hunted down, but only receiving visitors with greetings from his family. He gave a shout of delight, and his wife came out from the snow hut and joined in the welcome.

Later, Igsivalitaq gave me an account of the circumstances which had led to his act of homicide—and certainly, he had acted under considerable provocation. I advised him in any case most earnestly to make no attempt at escape in the event of his being sought for by the Mounted Police, and above all not to resist capture by armed force; it was unlikely, I thought, that he could be punished very severely. At the same time I endeavored to instil into him some idea as to the sacredness of human life and the wickedness of killing a fellow-man; my exhortation here, however, was unfortunately impaired in its effect by what the poor outlaw himself had heard, through some traders from Repulse Bay, as to the doings of the white men in the Great War.

On the following day, under Igsivalitaq's guidance, we filled up our stores from the depot of seal and caribou meat, and drove on again to a camp of snow huts some distance out in the fjord.

Arviligjuaq, "The Land of the Great Whales," is a term used to denote the whole of the Pelly Bay district, and is derived not from any actual prevalence of whales in those waters—as far as I could learn, there are none—but from some hill formations on land, which viewed from a distance present the appearance of whales.

The people here were Arviligjuarmiut, a tribe related to the Netsilik group, but holding apart from them as regards their territorial limits, and keeping to the district between Lord Mayor's Bay and Committee Bay. This winter, they numbered in all but fifty-four souls, men, women and children, divided among three settlements, two on the ice in Pelly Bay and a third on the west coast of the Simpson Peninsula.

The whole region seemed to be one of plenty, and the Arviligjuarmiut informed me proudly that the scarcity and famine, such as the Netsilingmiut west of Boothia Isthmus often suffered, were altogether unknown among themselves. This was due to the variety of game at their disposal in sequence throughout the year; caribou, musk ox, seal and fish; should one form of hunting fail, there was always another to fall back on.

The Arviligjuarmiut, whose country lies right off the routes followed by white men through these regions, have from the first learned to rely on such material as their own territory afforded for the making of weapons and implements generally. Knives are made from a kind of yellowish flint, brought from a considerable distance, in the neighborhood of Back's River. Fire was obtained from "Ingnerit," i.e., firestone, iron pyrites, found near the sea west of Lord Mayor's Bay. Sparks were struck so as to fall on specially prepared tinder made from moss soaked in blubber. Soapstone for lamps and cooking pots was procured from the interior south of Pelly Bay.

The greatest difficulty was the scarcity of wood. Owing to the masses of drift ice always collecting out in Boothia Gulf, drift wood never came up into the fjord; the nearest place where it could be obtained was on the shores of Ugjulik, west of Adelaide Peninsula. Mostly, however, the natives here learned to manage without wood; they made long slender harpoon shafts of horn, the pieces being straightened out laboriously in warm water and joined length to length. Tent poles were fashioned in the same way, only one being used for each tent. Owing to the scarcity of iron and flint, harpoon heads were made from the hard shinbone of the bear.

When summer was at an end, and the tents no longer required, they were turned into sledge runners. This was done by laying out the skins in a pool to soak, and when thoroughly softened by this means, folding them over and over into long narrow strips of several thicknesses, and leaving the whole to freeze hard in the shape of a runner. Musk ox skins were used in the same way. These runners of frozen skins were further strengthened by a packing of raw fish or meat between the layers, the whole being frozen to a compact mass. Then in the spring, when warmer weather set in and the sledges thawed and fell to pieces, the tent skin runners did final service as food for the dogs, and the meat "stuffing" as food for their masters.

There were originally two trade routes offering means of communication with tribes from whom iron and wood could be procured in case of need. One was via Rae Isthmus down to Chesterfield, where, before the new trading station was established, knives could be procured from natives who had been down to Churchill. The other was across Back's River to Saningajoq, the country between Baker Lake and Lake Garry, and thence to Akilineq, the famous hill district on the Thelon River, where the Eskimos from the shores of the Arctic used to meet the Caribou Eskimos for purposes of trade. Wood, in particular, was brought from here.

And these hardy folk were not afraid of making long journeys by sledge, being away sometimes for a whole year, in order to procure some luxury which they could well do without; on the other hand the possession of a real knife, or a wooden sledge, conferred a certain distinction upon its owner, while the woman who could make and mend her husband's clothes with a needle of iron or steel was an object of envy among her less fortunate sisters.

It is generally believed that the wreckage of the Franklin Expedition was of great importance in the domestic economy of the North-west Passage Eskimos, and in particular, that their supplies of wood and iron were for years obtained from this source. I never found any confirmation of this; on the other hand, I did find that the Eskimos right from Committee Bay to Back's River, from King William's Land to the Kent Peninsula, possessed implements whose origin could be traced back to the John Ross Expedition, which appeared in Lord Mayor's Bay in the autumn of 1829 and wintered there. The natives round Pelly Bay had still many reminiscences of this expedition, and the sober fashion in which they spoke of these experiences, now nearly a hundred years old, goes far to show how trustworthy these Eskimos are when dealing with anyone who understands them.

They state that John Ross's ship was first observed early in the winter by a man named Avdlilugtoq, who was out hunting seal. On perceiving the great ship standing up like a rocky island in a little bay, he moved cautiously towards it, as something he had not seen before. The sight of its tall masts, however, convinced him that it must be a great spirit, and he turned and fled. That evening, and throughout the night, the men held council as to what should be done. Ultimately, it was decided that if they did not take active measures themselves, the great spirit would certainly destroy them; they therefore set off on the following day, armed with bows and harpoons, to attack it. They now discovered that there were human figures moving about beside it, and therefore hid behind blocks of ice in order to see what manner of beings these might be. The white men, however, had already sighted them, and came towards them. They stepped out then from their hiding places to show they were not afraid. The white men at once laid down their weapons on the ice, and the Eskimos did the same; the meeting was cordial, with embraces and assurances of friendship on both sides, though neither could understand the other's tongue. The Eskimos had heard of "white men" but this was the first time that any had visited their country. The white men afterwards gave them costly gifts-all manner of things which they could never have procured for themselves-and there was much intercourse between them, the natives going out with them on journeys and helping them in various ways from their knowledge of the country. The names of some who went out more often than the rest with the white men are still remembered: as Iggiararsuk, Agdlilugtoq, Niungitsoq and Ingnagsanajuk.

After the first winter, the ship was beset by the ice and ultimately sank in Itsuartorvik (Lord Mayor's Bay), but the "insides" of the ship were saved, being carried on shore in boats to Qilanartut; and when the strangers finally went away for good, they left behind them a great store of wood, iron, nails, chain, iron hoops and other costly things, which are still in use at the present day in the form of knives, arrow heads, harpoon heads, salmon spears, caribou spears and hooks. Some time after, a mast came ashore, and from this sledges, kayaks and harpoons were made. The mast was first cut up by saws made from barrel hoops; it took them all the summer and autumn to do it, but there was plenty of time.

There are interesting stories current also as to the Franklin Expedition. One old man named Iggiararjuk relates as follows:

"My father, Mangak, was out with Terqatsaq and Qavdlut hunting seal on the west coast of King William's Land, when they heard shouts, and perceived three white men standing on the shore and beckoning to them. This was in the spring, there was already open water along the shore, and they could not get in to where the others stood until low water. The white men were very thin, with sunken cheeks, and looked ill; they wore the clothes of white men, and had no dogs, but pulled their sledges themselves. They bought some seal meat and blubber, and gave a knife in payment. There was much rejoicing on both sides over the trade; the white men at once boiled the meat with some of the blubber and ate it. Then they came home to my father's tent and stayed the night, returning next day to their own tent, which was small and not made of skins, but of something white as the snow. There were already caribou about at that season, but the strangers seemed to hunt only birds. The eider duck and ptarmigan were plentiful, but the earth was not yet come to life, and the swans had not arrived. My father and those with him would gladly have helped the white men, but could not understand their speech; they tried to explain by signs, and in this way much was learned. It seemed that they had formerly been many, but were now only few, and their ship was left out on the ice. They pointed towards the south, and it was understood that they proposed to return to their own place overland. Afterwards, no more was seen of them, and it was not known what had become of them."

And lest any doubt should remain as to the veracity of his account, Iggiararjuk mentions the names of all those who were in the camp when the white men came: Mangak and his wife Qerneq, Terqatsaq and his wife Ukaliaq, Qavdlut and his wife Ihuana, Ukuararsuk and his wife Putulik, Panatoq and his wife Equvautsoq.

Among other visits from white men, they remember those of John Rae in 1847 and 1854.

I am quite ready to admit that there is nothing particularly exciting about these reminiscences in themselves, but this very fact: the lack of any special interest in the episodes, affords proof of the memory and reliability of these Eskimos. Their encounters with the white men were of the most casual order, and there was no time for them to become closely acquainted with the strangers; nevertheless, the accounts of such meetings are preserved, even after this long lapse of years, in a manner which speaks for itself as to their reliability. And if we look up the official reports of the respective expeditions concerned, we find that the native tradition is in excellent accord with the facts there stated.

The last day was given up to sports of various kinds, among which target shooting with bow and arrow was particularly effective. The targets were life size figures built of snow. And I noted here, that while the arrows might strike at a distance of 100 metres with force enough to kill, the shooting at this range was very uncertain. Accurate shooting was limited to a distance of 20 to 30 metres. Most of the men of course possessed firearms, which would naturally lead them gradually to neglect their practice with the bow and arrow. Nevertheless, the musk ox hunting of the previous autumn, in the neighborhood of Lake Simpson, had been carried out exclusively with bow and arrow, and twenty or thirty beasts would be brought down by this means.

The same evening, I had a visit from a man named Uvdloriasugsuk, who had come in from his camp a day's journey to the north-west. He was a big, broad-shouldered fellow with a long black beard; a steady and reliable man, greatly esteemed by all who knew him. Nevertheless, he had shot his own brother the winter before. And it was in connection with this killing that he wished to see me. The brother, it appeared, was a man of unruly temper, who went berserk at times, and had killed one man and wounded others in his fits. His fellow villagers therefore decided that he must be killed, and Uvdloriasugsuk, as head of his village, was deputed to act as executioner. Much against his will, for he

On the following morning we took leave of our hosts and set off in different directions.

The dogs would wait no longer. I sprang to the sledge and waved a last goodbye as we drove off.