Across Arctic America/Chapter 13

Chapter XIII

Going Pretty Far With the Spirits

One day when we were lying out in Pelly Bay east of Boothia Isthmus, two men came running up out of the blizzard in front of the hut.

It was like a naked man suddenly knocking at the door. They had no sledge, no dogs, and carried no weapon save their long snow knives. And this was the more extraordinary since their dress showed that they came from a distance.

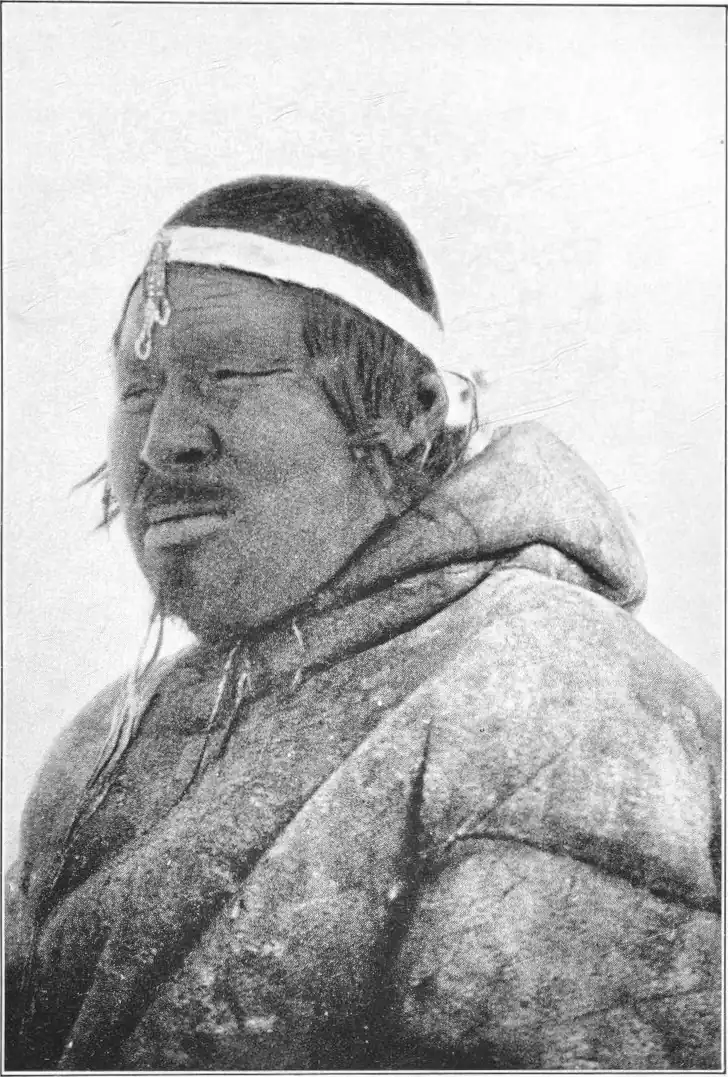

We got them in and thawed them up a little, and after a good meal they were able to give an account of themselves. They were two brothers from the neighborhood of the Magnetic Pole, out with a load of fox skins which they were going to trade for old guns with the natives at Pelly Bay. Qaqortingneq, the elder, was turning back now; and we decided to go back with him to visit his tribe.

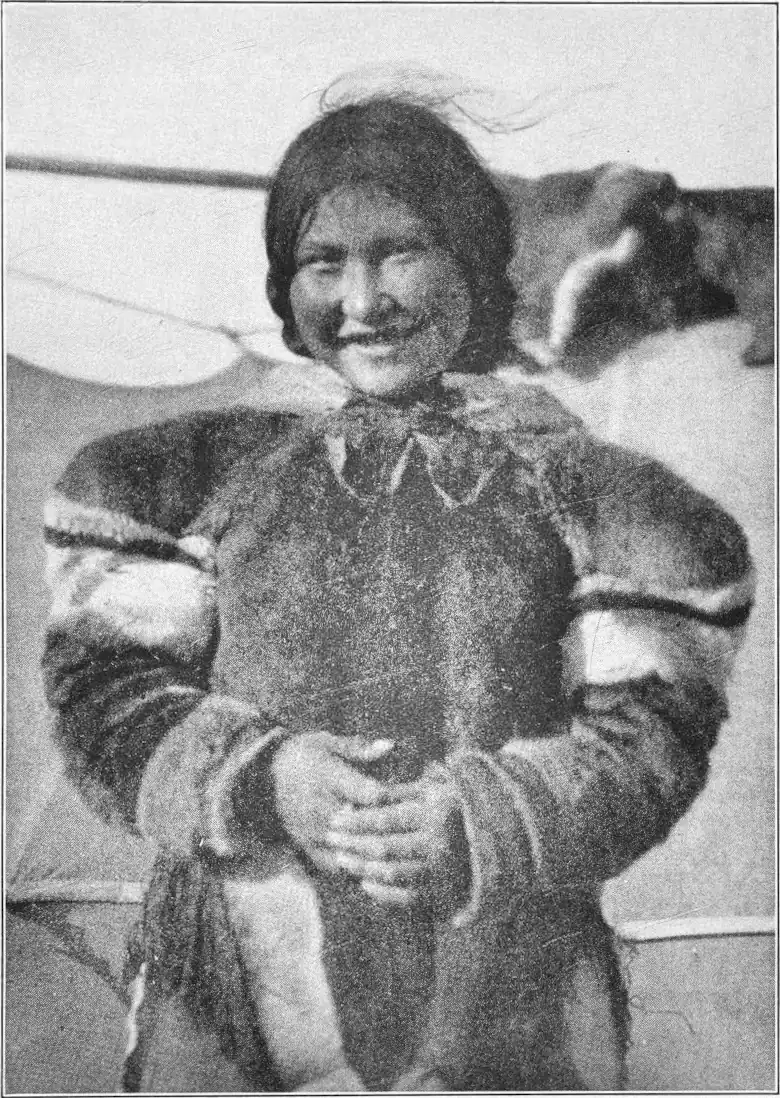

The rest of his party were in camp some distance off; he brought them up and introduced them; two wives and a foster son. Quertilik, the prettier of the two women, had, he explained, cost him a whole wooden sledge; the other, Qungaq, had been purchased for the modest price of a bit of lead and an old file. He explained, however, that he had got her cheap, as her husband had just died of hunger. The boy had been bought in infancy, for a kayak and a

We did a little trading, ourselves, and I secured a blue fox skin for our collection at the price of a few beads. On the following morning we struck camp and set out together across Franklin Isthmus, making for an encampment of Netsilingmiut out on the ice between King William's Land and Boothia Isthmus.

On the 3rd of May we camped north of the Murchison River, in a great plain leading down to Shepherd Bay. An endless expanse of white spreads all around, broken only here and there by a few isolated hillocks jutting up like seals' heads from the waste. Qaqortingneq was an intelligent fellow, and thoroughly acquainted with the Netsilik district; also, he drew excellent maps. The camp, however, had been shifted since he left it, and it was not until the evening of the 5th that our dogs picked up the scent. Even then it was not the camp itself, but a curious indication. Ahead of us on the ice lay a long line of seal skulls, with the snouts pointing in a particular direction. This Qaqortingneq explained was the work of the hunters on shifting camp, it being generally believed that the seal would follow in the direction in which the snouts of the slain were set. In the present instance, it served as a guide to us, pointing the way the party had gone.

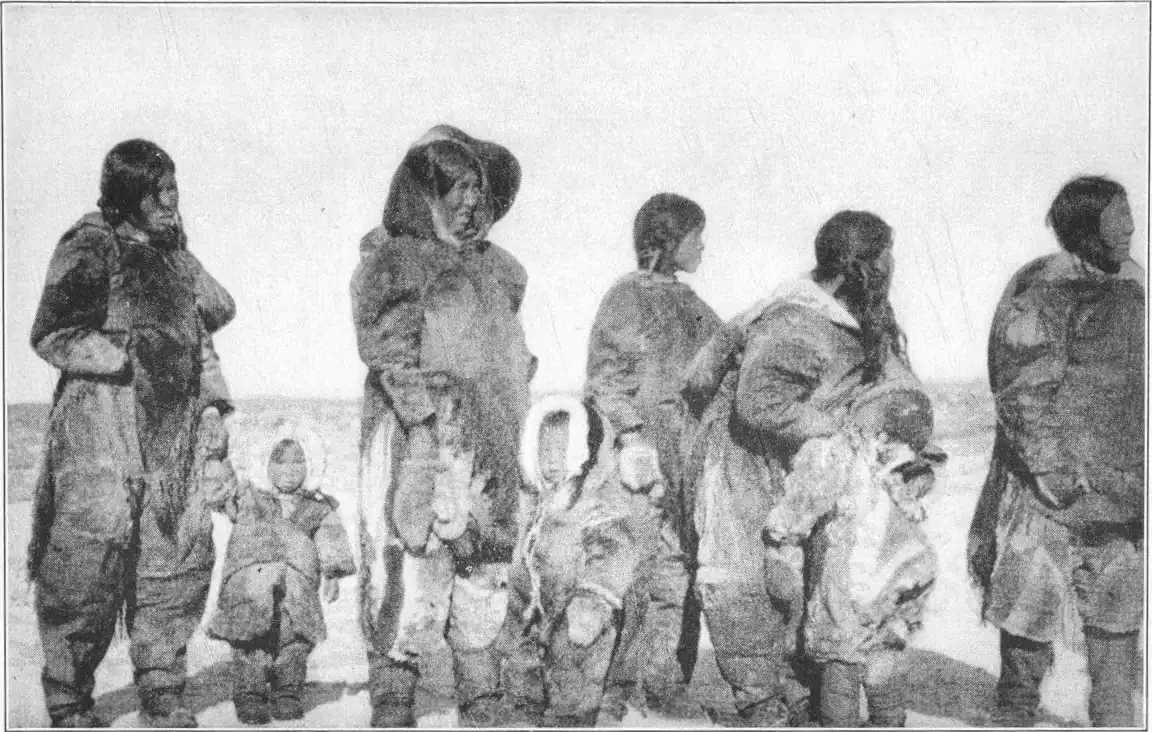

After some fruitless chasing about among confusing tracks, we came upon the village. Great blocks of snow were set up round it, not for shelter, but as frames on which to lay out the skins to dry. The people of Kuggup Panga (The River Mouth) had evidently no need of sheltering walls; they had, however, set up spears and harpoons in the snow outside their huts, and long snow knives above the doorways, to keep off evil spirits.

No white man had visited these people since the coming of Amundsen twenty years before, and I was a little anxious as to how they would receive us. Coming upon them as we did in the middle of the night there was no time for much in the way of explanation.

I crept into a house, together with Qaqortingneq's foster-son, Angutisugssuk, who was one of the party that had accompanied us from Pelly Bay. It was his mother's house we now entered.

"Here are white men come to visit us," he cried excitedly. His mother jumped up at once from a bundle of dirty skins, knelt down on the sleeping bench and bared her breast, which the boy hurried forward to kiss. This is a son's greeting to his mother on returning from a long journey. In the midst of these squalid surroundings, this recognition of the bond between them, the son's homage to the mother's breast, was to me doubly impressive.

We had hardly made ourselves known to them when I observed that the women were gathering in an odd sort of order about our sledges; and soon they began marching round them in solemn procession. On enquiring the reason for this I was informed that it was a ceremony designed to ward off any possible danger from the "spirits" which had accompanied us on our way unknown to ourselves.

By the time we had unloaded our goods and gear, friendly hands had built a hut for us, and we were hardly settled in our quarters when two huge seals were dragged up before the door as food for ourselves and our dogs.

Early the next morning we were awakened by the unceremonious entry of the village wizard, one Niaqunguaq. He was in a trance, and talked in a squeaky falsetto; the burden of his message being that his "helping spirits" had visited him during the night and declared that Qaqortingneq had eaten of forbidden food, videlicet, the entrails of salmon, while in our company. This is tabu during the seal hunting season. It was a safe guess anyhow, as the frozen fish were there among our stores when we unpacked the sledge, plain for all to see. Incensed authority was pacified, however, by the fragrance from our coffee pot, which I had quietly put on the oil stove while he was capering about. I took the opportunity to question him further as to these helping spirits of his, and learned that he counted about a score. One was a naked infant he had found sprawling on the bare earth far from human habitations; another was an Indian who had appeared to him with icicles in his hair and a flint knife stuck through his nose; a third was a lemming with a human face, which could also take the form of an eagle, a dog or a bear. This lemming was his special guardian angel. Despite the importance thus conferred, and his dignity as a wizard, he was not above enjoying a mug of coffee, and when he left, we were on the most friendly terms.

We spent the rest of that day going visiting from hut to hut. I soon discovered that we were in a hunting camp, where all were intent upon the most pressing of all our human occupations, the getting of their daily bread. It would be better therefore, for my purpose, to call on them some other time, later in the year, when they had settled in King William's Land. I decided accordingly to move on to the Magnetic Pole, where there was said to be a big camp. I myself was anxious to make a collection of amulets from among the Netsilingmiut, where they were in use to an extent beyond what was customary with other tribes.

On the 11th of May I took leave of my comrades and set off to the northward through Rae Strait, taking with me one Alorneq, whose personality is best indicated by the fact that his gums were always dry from constant smiling.

We had no very precise idea as to where our people were to be found, as camps in the spring shift with the movements of the seal. We had first of all to get up to the north of Matty Island and into Wellington Strait, where we might hope to come upon sledge tracks leading in the right direction. It was difficult indeed to keep any sort of direction here. The compass itself was useless owing to the proximity of the magnetic pole, and the low south-eastern shore of King William's Land with Franklin Isthmus, is hardly to be distinguished from the sea ice, while the few mountain ranges are always wrapped in a veil of driving snow. We drove for two days without sight of a landmark anywhere; then we got a glimpse of the south-west coast of Boothia Isthmus, and on the third day went on up through Ross Strait, where we knew there had been a camp earlier in the winter. A fresh north-easter was blowing as we passed the north coast of Matty Island, and in Wellington Strait we began to look about on the chance of sighting bear, which not infrequently come in here hunting seal on their own account.

It was at Cape Adelaide, close to the Magnetic Pole, that we came upon the first snow huts; these were deserted, but the quaint little "offerings" of seal skulls pointed the way the hunters had gone; we followed up their tracks, and came upon more huts, first five, then three, then twelve, and then twelve again.

Alorneq is a magnificent tracker; he knows people by the way they build their huts, the way they lie down to sleep, as well as by their actual spoor, and long before we come up with the party he is able to tell who they are. When we did come upon them it was with a certain suddenness, our dogs disappearing headlong out of sight in what proved to be the entrance to a hut.

Alorneq went from one to another announcing our arrival, all turned out without the slightest hesitation and helped us to rights, and we were soon settled among them as comfortably as could be.

Amulet hunting is rather a delicate business, and I had to proceed with care. My business was to obtain, in the name of science, all that I could of these little odd trifles which are held by the wearers to possess magic power, and worn as a protection against ill. But it had to be done in such a manner that I should not be held accountable afterwards for any evil that might befall those who had parted with their treasures.

I spent the first day making myself known to all, and seeking as far as I could to win their confidence. This meant, incidentally, partaking of generous meals at the shortest intervals-for after all, humankind is much alike all over the globe, and one of the best ways of getting to know your neighbor is to dine with him.

Meantime, Alorneq had unpacked the trade goods and set them out for all to see. There were brand new glittering needles, taken out of their papers and laid in a heap, there were knives and thimbles, nails and matches and tobacco—little ordinary everyday trifles to us, but of inestimable value to those beyond the verge of civilization. I was pleased to note that there was a constant stream of visitors to our little exhibition.

That evening, on returning to the hut, I found it packed with eager men and women. All had something to offer in exchange, principally skins such as traders usually ask. There was a murmur of disappointment when I announced that I did not propose to trade on the usual lines. I explained that I had come from a distant land in order to learn the customs of other tribes, and had visited them in particular on account of their amulets, of which I had heard so much. I then gave them a lecture on the subject of amulets and their power, the gist of which was that as I was a foreigner from across the wide seas, the ordinary rules and regulations applying to amulets, tabu and the like did not apply to me. I had in the meantime made the acquaintance of their own medicine man, and quoted him in support of my arguments, together with other authorities—famous angakoqs of other tribes, whose names, it is true, they had never heard before, but whose words nevertheless carried weight. I pointed out that an owner of an amulet still enjoyed its protection even in the event of his losing the amulet itself—and this was agreed. How much more then, must he retain its protective power when, by giving away the article itself, he secured the material advantage of something valuable in exchange? Needless to say, I emphasized the fact that I was not trying to buy the power of the charm, which must remain with the original owner, but only the article itself, and its history.

Despite all arguments, it was plainly a matter that required thinking over. I left them to sleep on it, and decide next day whether they would trade or not.

It was late next morning before we awoke and removed the block with which the entrance to a hut is closed at night. This was a necessary preliminary to our receiving visitors, as it is not considered good manners to call on people until their hut had been opened.

Alorneq and I made some tea and had some breakfast, but nobody came along. I was beginning to fear the worst when a girl strolled casually down. towards the hut and stood hesitating. I had noticed her the day before, admiring some of our beads. We invited her to come in, and she crawled through the passageway with all the amulets she was wearing on behalf of her son—when she should have one. Women rarely wear amulets on their own account. The Eskimo idea is that it is the man and not the woman who has to fight the battle of life, and consequently, one finds little girls of five or six years old wearing amulets for the protection of the sons they hope to bear—for the longer an amulet has been worn, the greater is its power.

This girl, whose name was Kuseq, now handed me a little skin bag containing all her amulets, newly removed from various parts of her clothing, where they were generally worn. I took them out and examined them, a pitiful little collection of odds and ends, half mouldy, evil-smelling, by no means calculated to impress the casual observer with any idea of magic power. There was a swan's beak—what was that for? Very sweetly and shyly the girl cast down her eyes and answered: "That I may have a manchild for my first-born."

Then there was the head of a ptarmigan, with a foot of the same bird tied on; this was to give the boy speed and endurance in hunting caribou. A bear's tooth gave powerful jaws and sound digestion; the pelt of an ermine, with skull attached, gave strength and agility; a little dried flounder was a protection against dangers from any encounter with strange tribes.

She had still a few amulets besides, but these she preferred to keep, so as to be on the safe side. Meantime, a number of others had found their way into the hut, young men and women, who stood round giggling and adding to our first customer's embarrassment. But their scornful smiles gave place to wonder when they saw what we gave her in return; beads enough for a whole little necklace, two beautiful bright needles and a sewing ring into the bargain. The girl herself could not conceal her satisfaction at the deal; and when she went out, I realized that this little daughter of Eve had set just the example that was needed.

In a couple of hours time there was such a run on the shop that I was really afraid the premises would be lifted bodily from their foundation, and before bedtime I was able to announce that we had "sold out." In return, I had a unique collection of amulets, comprising several hundred items.

Among those most frequently recurring and considered as most valuable, were portions of the body of some creature designed to convey its attributes; as the tern, for skill in fishing, foot of a loon, for skill in handling a kayak, head and claw of a raven, for a good share of meat in all hunting (the raven being always on the spot when any animal is killed), teeth of a caribou, worn in the clothing, for skill in caribou hunting. A bee with its brood sewn up in a scrap of skin gives "a strong head"; a fly makes the person invulnerable, as a fly is difficult to hit. One of the few amulets worn by women on their own account is a strip from the skin of a salmon, with the scales along the lateral line; this is supposed to give fine strong stitches in all needlework.

We packed up our collection and stowed all away, ready to move off the next morning. Our departure was delayed however, at the last minute, by a visit from the local medicine man, whom I had, as already mentioned, appealed to as an authority in support of my theory as to the harmlessness of the transaction. He now demanded further payment in return. It was plain, he said, that I must be a man of remarkable power myself, and a lock of my hair, for instance, would be most valuable as an amulet in the event of trouble with spirits later on. He suggested that I should give a piece to each of those who had traded with me. I was rather taken aback at this; with every wish to give my friends a fair deal, I could not but remember that it was winter, in a chilly climate, and I was loth to set out on my further travels entirely bald. We compromised therefore with a few locks of hair for the most important customers, the rest being satisfied with bits of an old shirt and tunic divided amongst them.

The actual haircutting was the worst part of it, each lock being shorn, or rather sawn, off by the wizard himself with a skinning knife, and not over sharp at that. Scissors were unknown among these people. And by the time he had done with me, I am afraid my appearance was hardly what my hairdresser at home would consider that of a gentleman.

Finally, we got away about midday, instead of at