Across Arctic America/Chapter 14

Chapter XIV

An Innocent People

The visit of Back, in 1833, was the first ever paid by white men to the Utkuhikhalingmiut-the name generally given to the natives inhabiting the delta and lower reaches of the Great Fish River. The word means "Dwellers in the Land of Soapstone" and refers to a deposit of the mineral south of Lake Franklin.

The white men were very kind, and gave the natives handsome and costly gifts. Nevertheless, so runs the tradition, there was a great fear of the strangers, and the angakoq had said that no good was to be looked for from that quarter. Therefore, when the white men took their departure, after only one night's stay, an elder of the tribe stood forth on a rock in the river and uttered a spell to prevent them from ever returning. "And that was in the olden days, when there was yet power in magic spells." Hence the fact that no white men have ever settled among the Utkuhikhalingmiut since that day.

Certainly, the story is in agreement with the facts insofar as the people of this region, near the mouth of the Great Fish River, as well as the kindred tribes farther up inland, are among the least known of all the Eskimos. No one has made any stay among them, and there is no description extant of their life and ways. The one occasion on which any Arctic expedition came into contact with them was the visit of Back above mentioned, in 1833, and this was a matter of a few hours only, the more unproductive from the fact that none of the white men understood the Eskimo tongue. The same was the case in 1855, when James Anderson, of the Hudson's Bay Company, following Back's route, encountered them on his way down to Montreal Island seeking news of the Franklin Expedition. And finally there was Schwatka, who in 1879 passed a settlement on the Hayes River on his way to King William's Land, likewise in search of news as to the fate of Franklin's men. None of these travellers could say more than that they had come upon a remarkable people in these regions; naturally therefore, I was eager myself to make their acquaintance.

Miteq and one of the Netsilik natives were to go on to the trading station of the Hudson's Bay Company, at Kent Peninsula, taking such collections as we had accumulated up to date and bringing back various supplies, notably of ammunition, some of that intended for our own use having been already disposed of in the way of exchange. We were to meet on the west coast of King William's Land, at the settlement of Malerualik, where most of the natives from that district would then be assembled for the fishing and caribou hunting.

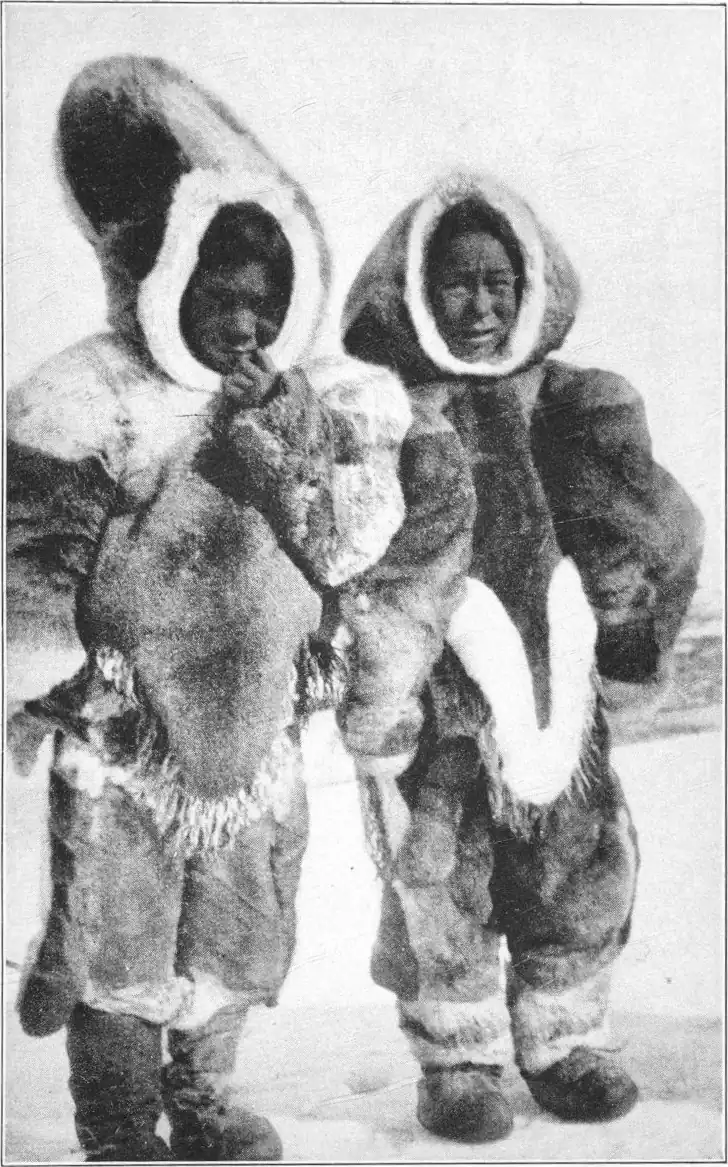

I myself had with me Anarulunguaq and a Netsilik native called Inugtuk, with his wife Naulungiaq and two young sons. They were on their way to Lake Franklin to barter hide and blubber for powder and lead among the inland Eskimos there. Inugtuk was a skilful hunter, but like all the Netsilik, a very poor driver. And he proved an excellent comrade when I learned to know him a little better. At first I was inclined to regard him with some distrust, owing perhaps to what I had learned as to his antecedents. He had obtained his present wife by murdering her husband, Pujataq, at the same time adopting the two sons of the man he had killed. The whole family now lived together in the greatest harmony, and there seemed to be real affection between them all round—which was the more remarkable as the two lads would, on arriving at man's estate, be expected to take vengeance for the murder of their father. Inugtuk himself was a man of good family as such things go in these regions, and it was currently believed that his father had been carried up to heaven "as thunder and lightning" when he died.

According to the information I had received, the nearest settlement of the Utkuhikhalingmiut was at Itivnarjuk, near Lake Franklin, the same spot where they had been found in 1833 and 1855. The distance from there to the snow hut colony at south-west of Shepherd Bay was about 250 Km.

Early in the morning of the 31st of May, our dogs picked up the scent of something near at hand; and we were now just about the spot where we expected to find them. Sure enough, a few minutes later we drove full into a camp of nine tents.

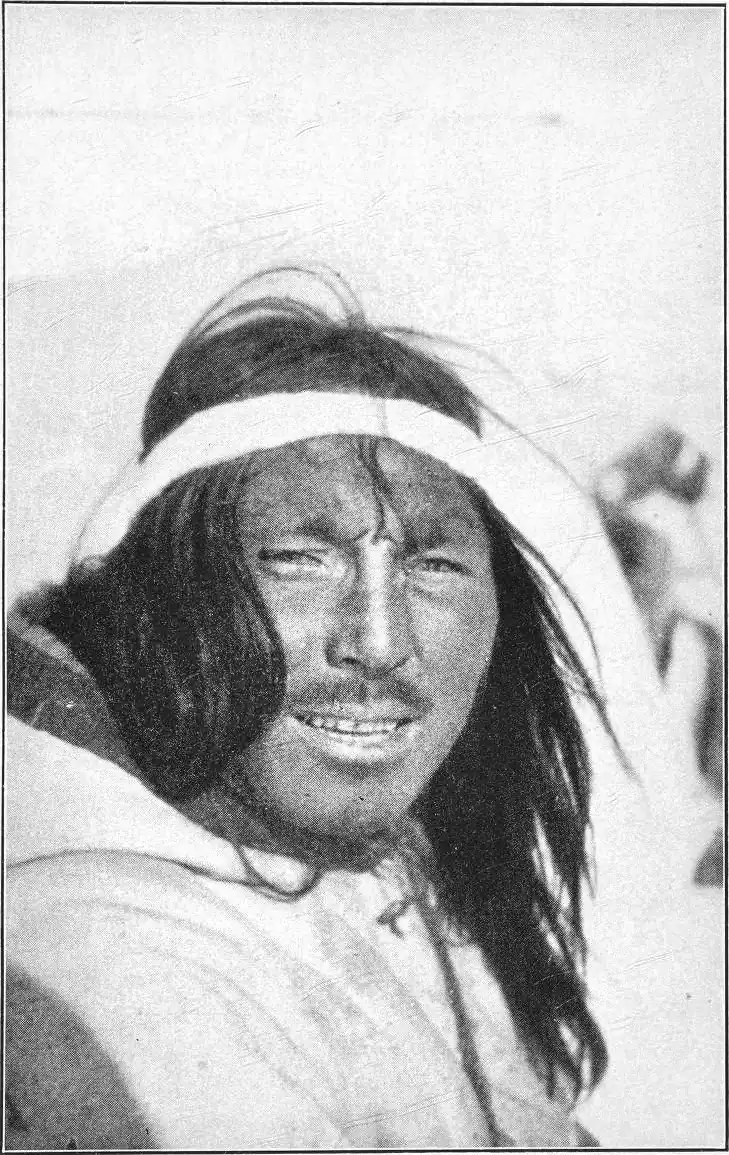

The natives here received us with a certain dignity. Despite the suddenness of our appearance, there was nothing of the shouting and confusion customary on such occasions. They could see at once from our clothes, our sledges and the manner in which our teams were harnessed, that we were strangers, and from a distance, but there was no rain of questions as to who we were and what we wanted, or the like. The men of the party came down towards us, not running inquisitively, but moving quietly and with some reserve. They were fine big men, well dressed, and with an earnest, almost solemn severity of countenance, more resembling Indians than Eskimos.

I explained who I was and what was my object in visiting them. The language occasioned no difficulty, and it was not long before they laid aside their first formal stiffness and began helping us to fasten the dogs, set up a tent and get our goods in order. This done, the spokesman of the party, whose name was Unaumitaoq, stepped up to me and looking me straight in the face, asked:

"Are you one of those white men who forbid the Eskimo to enter their tents?"

I explained that it was my earnest desire to learn as much as possible about my new friends in the short time I was able to stay there, and that anyone who cared to visit me would be welcome.

A murmur of approbation greeted this announcement. I added, that such trade goods and other property as I had with me would be left unguarded in the tent, since I took it for granted that they would be safe there. Upon which Ikinilik, one of the elders, answered proudly:

"Among our people, it is only dogs that steal."

I spent the rest of that day improving the acquaintance of my hosts. They had made a favorable impression on me from the first, and it was a relief indeed to find oneself among people positively clean, clean even to their hands and feet, after the indescribable dirtiness of the Netsilingmiut. They were, moreover, far more intelligent and quick of apprehension, and answered questions briskly and to the point. All were eager to give me information.

They were, I found, not altogether unacquainted with white men and white customs, though the nearest trading station was so far distant that it sometimes took half a year to get there and back. The journey was only made by the younger men, so that none of the older ones had ever seen a white man before.

Writing was a great source of wonder and amusement to them, and my journal, in which I was constantly making notes, occasioned much comment. All were delighted with the fineness of the paper leaves, which they took to be a specially delicate variety of skin. And when I wrote down what they said and afterwards read it aloud, they applauded; evidently, the "creature" had a good memory!

The Inland Eskimos, of the Great Fish River, or, as it is also called, from the name of its discoverer, Back's River, number only 164 souls in all, men, women and children. They divide themselves according to their villages into three groups, the Utkuhikhalingmiut in the Delta and lower reaches, especially the country south of Lake Franklin, the

Now, they use tallow in place of blubber for their lamps, that is, for lighting purposes; for cooking and heating they use lichen and moss and a kind of heather. As a matter of fact, there is very little cooking done, most of their food, both fish and meat, being eaten raw. Also, they dry their wet clothes on the body.

The temperature here is for several months of the year somewhere between minus 40° and minus 60° C. Nevertheless, these people declare that they do not feel the cold "much"; snow huts may be a little cold when newly built, but when covered with a good layer of fresh snow and filled with live human bodies, they soon get warm. The Utkuhikhalingmiut, indeed, regard themselves as much better off than the Netsilingmiut. Famine is not unknown, but is by no means of frequent occurrence, and only occurs when a long spell of extra bad weather prevents the men from hunting, or when the hunting itself proves fruitless both for caribou among the hills and fish in the lakes.

There is an old tradition to the effect that the Utkuhikhalingmiut were once a great people, so numerous that the hills around Lake Franklin were veiled in the smoke of their cooking fires. They were a warlike people, constantly fighting with their neighbors, and killing among themselves was of frequent occurrence.

As an illustration both of the spiritual culture and the manner in which it was revealed, I give the following account of an interview with Ikinilik, whom I have already mentioned as one of the elders of the tribe, and who was, also, a remarkable personality.

I tried to explain to him in the first instance, that I was interviewing him on behalf of a daily newspaper; that all that passed between us would be made known to many people through the medium of "talk-marks" such as he had seen me making in my note books, printed on sheets of the fine "skin" for men to learn what is happening each day.

But this in itself he regarded as a witticism, a humorous exaggeration; the world of the white men was big, no doubt, yet it could not after all be bigger than that a man might learn all the news there was by enquiring at the nearest tent.

In the following, I give question and answer word for word, according to my own notes written down, on the spot. It will be observed that the parts dealing with religious beliefs are to some extent a repetition of what has already been given in my conversations with Aua; I have retained these however, on purpose, as it seems worthy of note that two men from different parts, and of different types, should express almost identical views on the most important problems of life.

Ikinilik settled himself comfortably among the soft caribou skins, and lighting his pipe—the bowl of which was about the size of a small thimble—started off with a laughing allusion:

"From what you say, it would seem that folk in that far country of yours eat talk marks just as we eat caribou meat." And continuing the simile, he went on: "Well, now, begin with your questions and get your fire going; then I will cut up the meat and put it in the pot."

I began accordingly. "Tell me something about your religion. What do you believe?"

But at this all those present answered in chorus, so that I was barely able to distinguish Ikinilik's voice:

"We do not believe, we only fear. And most of all we fear Nuliajuk."

I tried again to explain to the party what an interview was. "Only one must answer," I said, and hoping they would take this as final, I went on:

"Who is this Nuliajuk?"

But every boy and girl in the place knew something of Nuliajuk from their nursery rhymes; it was too much to expect them to keep silence. All wanted to tell what they knew, and it was with difficulty that. Ikinilik could make himself heard above the rest.

"Nuliajuk is the name we give to the Mother of Beasts. All the game we hunt comes from her; from her come all the caribou, all the foxes, the birds and fishes."

I asked him then: "What else do you fear?"

And this time the others refrained from joining in. Apparently they had at last understood that the interview was a matter between Ikinilik and myself. Ikinilik answered:

"We fear those things which are about us and of which we have no sure knowledge; as, the dead, and malevolent ghosts, and the secret misdoings of the heedless ones among ourselves."

"Do all human beings turn into evil spirits when they die?"

"No; only when those nearest to them have neglected to observe the customs laid down from the time of death until the soul has left the body."

"And when does the soul leave the body?"

Ikinilik shook his head and smiled, with an expression almost of pitying condescension in his fine, wise eyes: to think that a grown man should be so inquisitive! The onlookers, too, were smiling as he answered.

"If it is a woman, five days after death; if a man, four."

But I was not to be deterred from my questioning, and went on:

"Is there anything else you fear?"

"Yes, the spirits of earth and air. Some are small as bees and midges, others great and terrible as mountains."

"What happens to the soul when it leaves the body?"

Ikinilik shifted in his place, and the wrinkles round his eyes deepened a little; of all the ridiculous questions.

"When people die," he began, in his slow, rich voice, "they are carried by the moon up to the land of heaven and live there in the eternal hunting grounds. We can see their windows from on earth, as the stars. But beyond this we know very little of the ways of the dead. Some few of the angakoqs in former times made journeys to the land of heaven, and told what they saw. They visited the moon, and in every case were there shown into a house with two rooms. Here they were invited to eat of most delicate food, the entrails of caribou; but at the moment the visitor reaches out his hand to take it, his helping spirit strikes it away. For if he should eat of anything in the land of the dead, he will never return. The dead live happily; those who have visited their land have seen them laughing and playing happily together.

"There was once a woman named Nananuaq; she died, and was carried off by the moon. But she did not stay long in the land of the dead; the moon changed her into a man and sent her back to her husband. The husband was very pleased to have his wife back again, but was sorely disappointed to find that she would not sleep with him. She told him what had happened, and when he had assured himself that it was the truth, he was so angry that he determined to kill her. He went out of the house to cut a hole in the ice: 'I must have water to drink,' he said, 'for that is the custom after one has died.' But the woman fled away to her grandchild, who lived near by, and when her husband came after her to fetch her back, she killed him as he entered the passage.

"This woman told her fellows on earth many things about life after death, and it is from her that we have our knowledge. Our angakoqs nowadays do not know very much, they only talk a lot, and that is all they can do; they have no special time of study and initiation, and all their power is obtained from dreams, visions or sickness. I once asked a man if he was an angakoq, and he answered: 'My sleep is dreamless, and I have never been ill in my life!' Now that we have moved up inland away from the sea we do not need to bother ourselves about what is tabu in connection with sea-beasts, and then also we have guns, which makes all hunting much easier than it was. Young hunters nowadays have too easy a time of it to trouble about consulting wizards. In the olden days when our food for the whole winter depended on the autumn hunting at the sacred fords, it was a very different matter; all the regular observances and many particular ones in addition were dictated daily by the angakoqs who knew all about such things. But now we have forgotten all the old spells and magic songs, and you will find no amulets sewn up in our inner garments. The people have food enough, and do not bother about their souls."

This opens the way for a question of importance.

"What do you understand by 'the soul?'" I asked.

Ikinilik was plainly surprised that I could ask such a thing; nevertheless he answered patiently:

"It is something beyond understanding, that which makes me a human being."

"Can you tell me any more about the life after death?"

Here the interview was brought to a close by the equivalent of the dinner gong, a summons which could not be ignored. It was moreover, my last public appearance among these friendly people, as I was leaving the same night. The river was breaking up and difficult to pass already.

Looking back upon my short stay among them, I cannot help noting that the esteem and admiration I felt for them at the time has been in no wise impaired by subsequent impressions elsewhere. I shall always look upon the Utkuhikhalingmiut as the handsomest and most hospitable, as well as the most cultured people of all those I met with throughout the whole length of my journey; and the cleanest and most contented to boot.

Oddly enough, the only information I had about them prior to my visit was from a letter written by Captain Joe Bernard, published in Diamond Jenness' book on the Copper Eskimos. Bernard, who went up to Victoria Land in 1918 and wintered there, based his opinion on the Netsilingmiut, and summarily disposed of the others in the following terse dictum:

"The Utkuhikhalingmiut are probably the most miserable people in the winter time I have ever seen or heard of."

Which shows how opinions may differ—and how careful one should be in forming an opinion as to one tribe from what one has heard through another.

It was a little after midnight when I started, and the whole village, men and women, turned out to see us off, wishing us all that was good out of their own abundant content. The mountains were already bathed in cold white light, and we were anxious to get well out onto the sea ice before the heat of the sun made the work too fatiguing for our teams. Amid a chorus of farewells from our friends we struck off over the great water. One might almost say: through it; for a mush of sodden snow and water came threshing up over the sledges, and we ourselves were soaked through at once, having to go down on our knees in order to heave the sledges clear when they stuck fast.

Altogether about as wretched going as one could wish for the starting of a journey, but we took little heed of it, and laughed as we plunged into the icy mess through which we had to toil that day. The snow-broth seethed about the runners, and we drove through it singing.