Across Arctic America/Chapter 16

Chapter XVI

From Starvation to Savagery

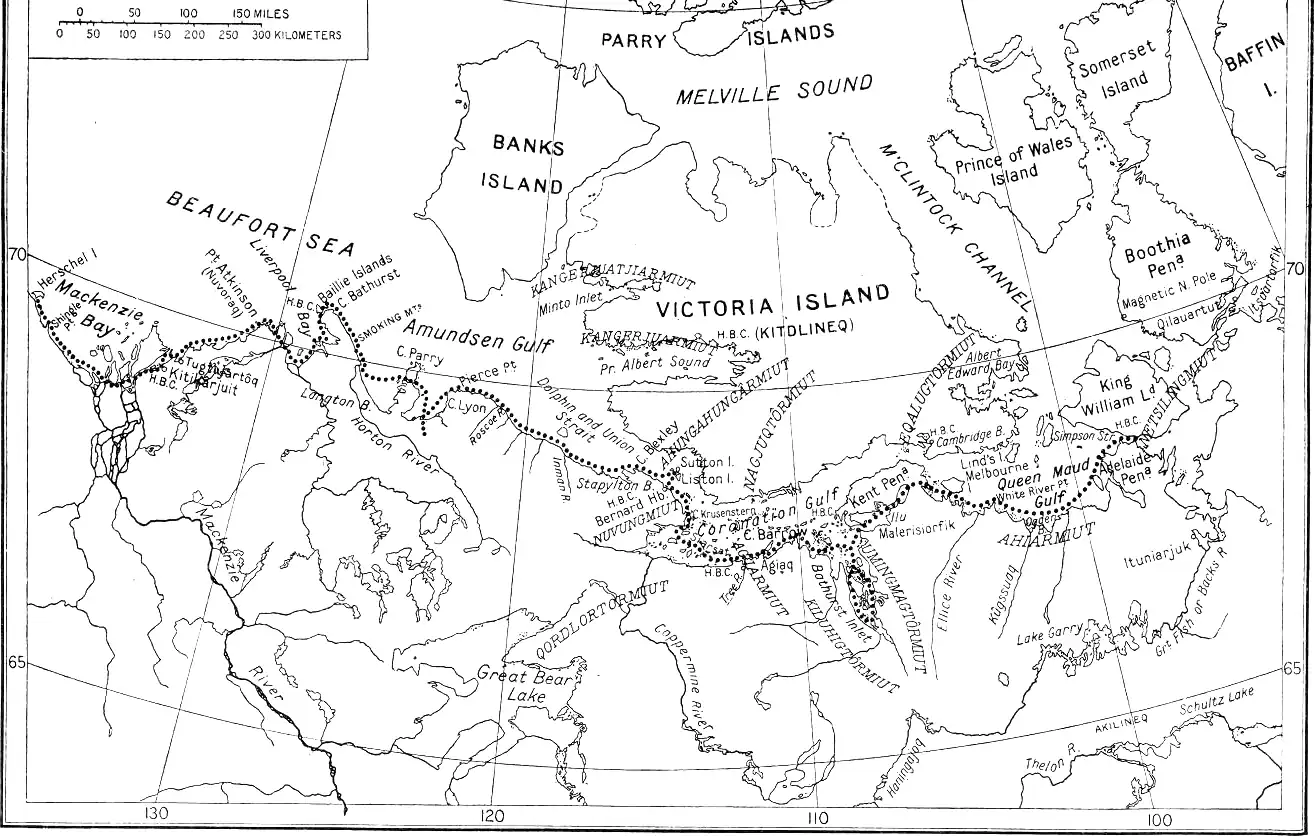

Shut off from the rest of the world by ice filled seas and trackless wastes of vast extent, the little handful of people who call themselves the Netsilingmiut have been suffered to live their own life, such as it is, up to the present day uninfluenced by any form of alien culture. Their own enumeration of the various tribes belonging to their people is as follows:

The Arviligjuarmiut, in the neighborhood of Pelly Bay, numbering 32 men and 22 women; the Netsilingmiut proper,[1] from Boothia Isthmus, 39 men and 27 women; the Kungmiut, from the banks of Murchison River, 22 men and 15 women; the Arvertormiut from Bellot Strait and North Somerset, 10 men and 8 women, and finally, the Ilivilermiut of Adelaide Peninsula, 47 men and 37 women, making a total of 259.

From mid-July until December, these people live up in the interior, occupied in caribou hunting and salmon fishing; the rest of the year is devoted to seal hunting on the ice. The name Netsilingmiut, which

Though few in number, Netsilingmiut cover a territory of considerable extent, their hunting grounds amounting to some 125,000 square kilometres, which is three times the size of Denmark, and equivalent to the entire ice-free portion of Greenland.

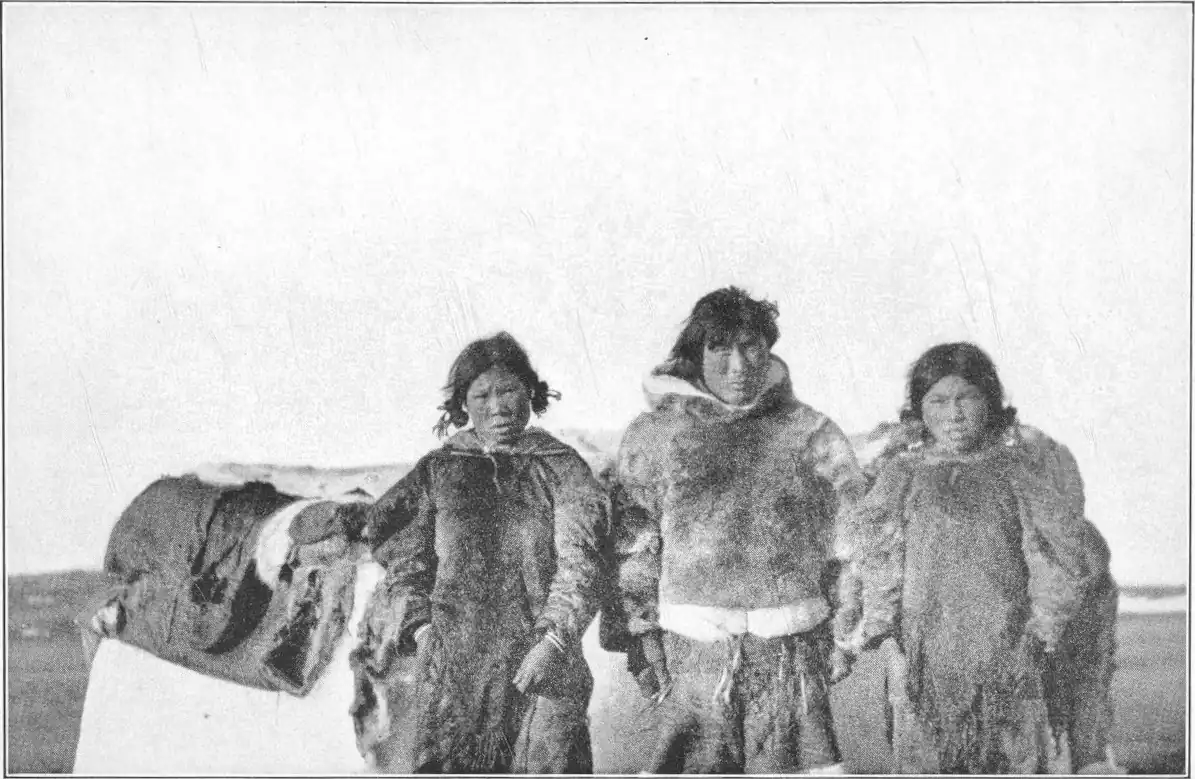

I lived among these people for over six months, and had every opportunity of learning to know them intimately, being forced myself to return to altogether primitive conditions and share their lot in every way; a fact which was naturally conducive to mutual confidence.

There is hardly any country in the world more harsh and unfriendly than theirs, or more destitute of all that is generally regarded as necessary to mere existence. Winter begins in September and lasts till the middle of July. During the actual winter months they have to struggle for life against a temperature somewhere between minus 30° and minus 50°C. I visited them in April, and marvelled how they could keep up their spirits—find room, indeed, for fun and merriment—in their cold and comfortless dwellings. In May, the weather was but little better; certainly, it was a trifle less cold, but in return, the constant blizzards wrapped the whole poor encampment of snow huts in a flurry of snow; and as soon as the sun came out for a spell, its chief effect was to melt the roof over their heads. But it did not seem to trouble them. And I thought to myself that when summer came, it must make amends, and give them compensation for all they had so bravely and patiently endured; surely they must at some season or other absorb the warmth that even animals cannot do without. The summer came, and I visited them up country at their salmon fishing. It was not positively cold now, but the weather was by no means pleasant, being dull and chilly, with a constant wind; the snow had given place to rain, and the little tents made but a sorry shelter. Nevertheless, the inmates were by no means depressed; on the contrary, they played games most of the day, going about in their wretched rags without a murmur at the stern tabu which forbade them even to make themselves new clothes or warmer sleeping rugs until they had shivered their way through the first of the snow right on into November.

And these step-children of Nature were by no means wretched in appearance; they were for the most part tall and strongly built; among the men, a height of 170 cm. was by no means uncommon. They were not only cheerful, but healthy, knowing nothing of any disease beyond the "colds" that come as a regular epidemic in spring and autumn.

A people must naturally be viewed in the light of their surroundings, and from what has already been said as to those of the Netsilingmiut, it will hardly be surprising to find the people themselves not only hardy and of great endurance, but with many harsh and forbidding customs savoring of the stone age.

The Netsilingmiut are remarkably well acquainted with their country, both as regards its natural conditions and its history from early times. Though altogether unaccustomed to the use of pencil and paper they were able in a surprisingly short time to draw outline maps, with a very considerable amount of detail. The actual distances might not be quite exact, but every lake and island, every headland and bay was noted so carefully that one could easily find one's way by these maps in altogether new country.

Their own tradition holds that the Netsilingmiut immigrated at some distant date into the country they now occupy, driving out the original inhabitants. These, as in the Hudson Bay district, were called Tunit. It is so long since the Tunit hunted seal and whale in the land of the Netsilingmiut that everything has changed since then. Land and water were different; in that "the seas were deeper"[2] so that great sea beasts such as the whale could then come in to their shores, whereas now they are only found right up in Bellot Strait. Evidence of their former presence in these waters is seen in the many bones of whale found among the ancient ruined dwellings. And in support of the assertion as to change in the level of the sea, old men cited the finding of a whale skeleton far up inland at Saitoq, east of Shepherd Bay. Near the lake of Qorngoq also, in the same locality, many skeletons of white whales have been found, while farther inland again, near Lake Qissulik, there is a mass of driftwood, now so rotted by the weather that it crumbles at a touch. But the waters now are so shallow that not even the ribbon seal from Queen Maud Gulf pass in through Simpson Strait, and hunting of marine animals is restricted to the little common fjord seal.

The Netsilingmiut accounts of the Tunit supplement those we obtained in the Hudson Bay district about the aborigines there. And when, in the course of the summer, I was able to excavate and examine the remains of twelve winter houses at Malerualik, I found that this material also confirmed our theories as to the migrations of the Eskimo.

The ruined dwellings at Malerualik, comprising in all 65 houses built of stones and peat, are the first that have ever been investigated in this area, and therefore of the greatest importance as a link between our finds in Hudson Bay and Baffin Land on the one hand, and the collections afterwards made in the western regions of Alaska and East Cape.

Though the whales, as already mentioned, no longer penetrate into these waters, we found a considerable number of bones of whale used for building material in the dwellings of these old houses, and a great majority of the implements found were made from the same material. We obtained something over 200 items in this category, witnessing to a type of Thule culture somewhat more adapted to caribou hunting than in other places where excavations were made. These finds here were also rather more primitive, showing an earlier stage of development than the Naujan relics from Repulse Bay. It is thus also more nearly allied to the Alaskan form of culture than the other Thule finds.

The main bulk of the ruins lay distributed along three separate lines, marking the site of former beaches, the highest being some 25 metres above sea level, at a distance of some 400 metres from the coast, suggesting that they must be at least as old as the ruins at Naujan.

As has already been indicated, there is no superabundance of food in these regions. There are, of course, times when more game is killed than can be eaten at once, especially during the great caribou hunting season, in autumn, or when the salmon fishing in summer is particularly good. But on the other hand, we have to reckon with periods in winter when weeks may pass without any possibility of procuring food; it is therefore absolutely essential to have a store in reserve. Life is thus an almost uninterrupted struggle for bare existence, and periods of dearth and actual starvation are not infrequent. Three years before my visit, eighteen people died of starvation at Simpson Strait. The year before, seven died of hunger north of Cape Britannia. Twenty-five is not a great number perhaps, but out of a total of 259 it makes a terrible percentage for death by starvation alone. And yet this may happen any winter, when there are no caribou to be had. It is hardly surprising then to find cannibalism by no means uncommon. In citing a typical instance here, as showing the merciless nature of the struggle for existence, I give both facts and comment in the words of my informant, which express, I think, the typical native point of view. The speaker is one Samik, a good hunter and a respected angakoq.

"Many people have eaten human flesh. But never from any desire for it, only to save their lives, and that after so much suffering that in many cases they were not fully sensible of what they did.

"You know Tuneq, Itqilik's brother. You have met him, and his present wife, you have lived with them and you know him to be a cheery soul, a man who loves to laugh, and one who is always kind to his wife. Well, now, one winter many years ago the the hunting failed. And some starved to death and others died of cold, and the living lived on the dead. And all at once Tuneq went out of his mind. He said the spirits had told him to eat his wife. He began by cutting bits from her clothing and eating them, then more bits, till he had bared her body in several places. Then suddenly he stabbed her to death with his knife. and ate of her as he needed and lived. But he placed the bones in their order as it is required to be done. when anyone dies. . . .

"But we who have endured such things ourselves, we do not judge others who have acted in this way though we may find it hard, when fed and content ourselves, to understand how they could do such things. But then again, how can one who is in good health and well fed, expect to understand the madness of starvation? We only know that every one of us has the same desire to live."

The terrible uncertainty of life in these regions accounts to some extent for the prevalence of more or less superstitious rites and the use of amulets. The Netsilingmiut hold the same views on the subject of amulets as the Igdlulingmiut, but use

Perhaps the most striking evidence of the stern conditions under which these people live is afforded by their strictly economical attitude towards the business of childbirth. Girl children are invariably killed at birth unless previously promised in marriage and thus provided for already. And this is not from lack of feeling, nor from any lack of appreciation of woman's part in life, which is recognized as indispensable; it is due solely to a recognition of the fact that no breadwinner can hope to provide for a family numbering much beyond the necessary minimum. A girl is merely an unproductive consumer in the family up to the time when she is able to make herself useful; and as soon as she arrives at that stage, she is given in marriage, and her utility falls to the share of another household.

Every man knows that he can only reckon on a few years of active life as a hunter, unless he should happen to be endowed with a sturdier constitution even than his fellows. After a while he finds himself unable to compete. If he have sons, these will as a rule be able to help him when his own strength begins to fail; and it is thus an advantage to have as many sons as possible, staving off the evil hour when one literally feels the noose about one's neck. For it is a general custom that old folk no longer able to provide for themselves commit suicide by hanging. Life is short, and we must make the most of it—that is the crude moral of it all. Moreover, it should be remembered that it takes three years at least before a child is weaned, during which period the mother does not as a rule give birth to others; parents can therefore ill afford to spend three years on a girl when they might hope to have a boy.

It has been generally believed that the Eskimos were a people with low birth rate as a whole. This is only true to a certain extent; the long period of nursing accounts to a great extent for the length of time between births.

At Malerualik, in King William's Land, I went through the whole settlement, enquiring of the women individually how many children they had borne, and how many girls had been killed, noting carefully the names and numbers in each case. The result, from the list before me as I write, gives, for eighteen marriages, a total of ninety-six children of which 38 were killed at once as girls not previously provided for. It is significant however, that of the 259 souls which make up the population of the Netsilingmiut, 109 are women as against 150 men. Despite considerable fertility therefore, it is evident that the race is on the way to extermination if the girls continue to be thus summarily killed off at birth.

As an instance of their fertility I may quote a case which came to my knowledge. Imingarsuk, aged about 60, whom I met at Committee Bay, had had 20 children; of these, 10 were girls killed in infancy, 4 died of disease, one son was drowned, leaving 4 sons and one daughter, whom I afterwards met, all fine healthy specimens of the race. I asked the mother if she did not regret the killing of the girls, but she answered, no, for if she had had to nurse all those girls, who were born before the boys, she would have had no sons at all. As it was, she loved her sons, who had secured relative comfort for herself and her husband in their old age, but had no sort of feeling for the infants killed, whom indeed she had barely seen. My list above quoted includes also two women with ten, two with eleven, and one with twelve births to their credit.

In the face of these hard conditions, the Netsilingmiut have developed a wonderful degree of ingenuity and endurance in the pursuit of that game on which their lives depend. Highest in this respect is their method of harpooning seal at the breathing holes. They rank first among all the tribes in this form of hunting, and their methods and apparatus are worth a brief description.

When the ice first forms, the seal noses and scrapes a small hole through which to breathe; the site is indicated by a slight rise, or bell-shaped protuberance of the ice above the rest. It is a comparatively easy thing to harpcon a seal at this stage, but the matter becomes vastly more difficult when the ice has thickened to some two or three metres, with a further layer of snow above. What exactly takes place may be seen from an account of a day's hunting.

Very early, before it is quite light, Inugtuk and I are roused from sleep, and a jug of boiling seal's blood is brought us. Still barely awake, we swallow the hot, thick soup with its abundance of blubber, knowing that we cannot expect to get another meal for the next ten or twelve hours. Then hurrying into our outdoor clothes, we join our companions, and the party, fifteen strong, sets out across the ice at a smart pace. It is bitterly cold, with a biting wind.

Each of us carries a bag slung from his shoulders, containing various minor requisites; the harpoon is carried in the hand. Dogs are used to pick up the blow holes by scent.

It took us three hours to find the first, which fell to the lot of Inugtuk. I remain with him, while the rest of the party scatter in various directions. Inugtuk now sets about his first preparations. First of all he cuts away the upper layer of snow, leaving the dome of ice exposed. Then, with an ice-pick at the butt end of his harpoon, he chips away at the fresh ice which has formed since the seal's last visit, scooping out the fragments with a spoon of musk ox horn. He then takes a "feeler," a long curved implement made of horn, and thrusts it down into the hole to ascertain the exact position of the bore, or vertical tunnel relative to the opening itself. This is a most important point, as the position of the seal when it comes up to breathe depends on this, and the direction of the harpoon thrust has to be determined accordingly. With the aperture immediately above the centre of the vertical shaft, a straight downward thrust will generally strike the animal, but where the aperture is a little to one side, there will be room for the harpoon to pass without touching. As soon as this has been ascertained, the snow is packed down again over the ice, and a hole pierced straight through it with the harpoon so as to give a clear thrust when the moment arrives.

The next implement called into requisition is the "feather." This consists of a stiff sinew from the foot of a caribou, into which is fixed a piece of swansdown at one end, the other being forked, so that the forks catch on either side of the opening, leaving the swansdown indicator just far enough down the shaft to be still visible from above. As soon as the seal comes up and begins to breathe, the "feather" begins to quiver, and the hunter strikes.

The harpoon itself consists of a shaft with a loose head, a line being attached to the latter, so that on striking, the head becomes fixed in the body of the seal, and at the same time comes away from the shaft, when the animal is held on the line just as a fish on the hook. It is then drawn up to the hole again and killed.

As soon as all was in readiness, Inugtuk spread out his bag on the snow in front of the hole and stood on it. This partly to prevent the snow from creaking underfoot, and partly as a protection from the cold. And there he stood, like a statue harpoon at the ready, and eyes fixed on the swansdown just visible below. Hour after hour passed, and I began to realize what an immense amount of patience and endurance are required for this form of hunting with the thermometer at minus 50°C. Four hours of it seemed to me an eternity, but there are men who have stood for twelve hours on end, in the hope of bringing back food for the hungry ones at home.

We had just decided to give it up when we saw that one of the others a little way off had got a seal. As soon as he had hauled it up, we hurried over to him to take part in the "hunter's meal" a regular procedure almost in the nature of a sacrament. All kneel down, the successful hunter on the right, the others on the left of the seal. A small hole is cut in the carcase large enough to extract the liver and a portion of blubber, the opening being then carefully pinned up to avoid loss of blood. The liver and blubber are then cut up into dice and eaten kneeling. For myself, I always felt there was something touching and solemn about this ceremonial eating of the first meat on which men's lives depend.

Our total bag that day was one seal, and fifteen men were out for eleven hours to get it. But my comrades were only too thankful that they had anything to bring home at all, which is certainly not always the case. On the other hand, one may get three or four in a single day. But seal generally are scarce here. I reckoned out that the average haul per man would be about 10 to 15 seal from January to June. At a village with 10 families numbering 37 souls in all, the winter catch amounted to only about 150 seal. A skilful hunter in Greenland would have been able to get about 200 in the same time, which shows the enormous difference in the general conditions of life.

The mind of the Netsilik Eskimo is like the surface of one of these lakes with which his country abounds: easily roused, but soon calm again. But coolness is regarded as a virtue, and whatever misfortune may occur, a man is rarely heard to complain. The fact is noted, and regarded as inevitable: so it is, and it could not have been otherwise. So that the visitor dwelling among them for a while finds them living to all appearance in careless content.

Man and wife are comrades. The woman may have been purchased for a sledge, or a kayak; perhaps for a bit of iron and a few rusty nails; but she is by no means regarded as a chattel without feelings. Theoretically, the husband has the right to deal with her as he pleases; her very life is in his hands, but in point of fact she is not ill-treated in the slightest degree. She has her own position in the home, which is marked not merely by freedom and liveliness of manner, but also by some authority, especially among the older women.

Children are regarded with a touching devotion, and in times of dearth, the parents regard it as a matter of course that the little ones must first be fed, even though there be not enough for all. Children adopted into a family—bought for some trifle as a speculation—receive the same treatment in every way; the "orphan" type, the wretched, neglected, half-starved father-and-motherless child so common in Greenland, is here entirely unknown.

There is a regular division of labor: it is the man's business to procure food, while his wife attends to all the work of the house. Her work, moreover, is highly esteemed, and a good needlewoman is greatly respected by her fellows. She holds property in her own right; articles such as lamps and cooking pots, sewing requisites and other household goods make up her marriage portion, and she retains them when the marriage is dissolved. Divorce is common where there are no children, and a woman may be married seven or eight times before she settles down for good. Children are regarded by the parents as a great blessing, and serve to knit the two more closely together.

Polygamy exists, but is not common, owing to the scarcity of women. Where a man has more than one wife, it is always a sign of distinction and unusual skill in hunting. Jealousy is not unknown, but wives in one household generally get on amicably together. Polyandry also occurs; a woman may not infrequently have two husbands. A man, of course, is helpless if he has no one to make his clothes, and two friends will occasionally "go shares" in a wife. Such arrangements do not, however, turn out well as a rule, among young people at any rate, and not infrequently end with the killing of one of the men. A woman cannot on her own account invite a man friend to share her husband's rights in her; this is the husband's privilege alone.

"Changing wives" for a short time is of common occurrence. The man's position is altogether one of considerable freedom, and it is regarded as perfectly natural that he should have intercourse with other women as often as any opportunity occurs. Consequently, a woman left alone while her husband is out hunting is exposed to some risk from the advance of other men; should she give way to any such, she will as a rule be punished by her husband. On occasion, however, it is the co-respondent who is

The freedom thus claimed by the man in the marital relation is by no means extended to the woman, who in this respect is considered her husband's property. Changing wives is effected without the least regard to the feelings of the respective wives, who are not consulted in the matter at all. Even where a woman definitely wishes to remain "faithful" to her own spouse, her constancy would not only be unappreciated, but would be regarded as disobedience, and punishable as such. It is indeed regarded as a sin: "the spirits do not like it."

Natural desire and economical necessity, combined with the fact that there are not enough women to go round, give rise inevitably to keen competition among the men, as well as to quarrels, not infrequently with a fatal termination.

In earlier times, there was also continual war with other tribes, and there are many stories of killing and even massacre. Since the coming of the white men to the Hudson Bay district, there had been peace with the tribes to the eastward, but relations with those on the west, especially in Victoria Land, were still somewhat strained. And to this day it is customary for sledge parties approaching a village to halt some distance off and send forward a woman as a herald of peace. During my stay among the Ilivilermiut I happened to hear one of the natives there giving an account of an encounter with the Kitdlinermiut which was the more valuable as the man was not speaking to me at all, but addressing himself to his own companions. The speaker was one Nakasuk, from Adelaide Peninsula, and his account was as follows:

"Many came out towards me. But without showing sign of fear I drove straight in among them and said:

"'Well, it is only me; and I am nobody much. If those here wish to kill me, it may be done without much risk, for there is none who would care to take vengeance.'"

"This was received with laughter, and one of the strangers stepped forward to my sledge and said:

"'Are you afraid?'"

"I answered: 'I am past the age when one is afraid of others. I have come alone into the midst of your camp, as you see; if I had been a coward, I should certainly have stayed at home.'"

"These words were greeted with much approval, and an old white-haired man gave me their welcome. He said:

"'You are a man, and you speak with the words of a man. You may stay among us without fear. No one will harm you.'"

The said Nakasuk, it should be noted was a man of middle age, with two wives and several sons, and a man of no little importance among his own people; actually, then, neither so old as to count life worthless himself, nor so insignificant that none would care to avenge his death. But the little dialogue is eloquent of the general feeling between one tribe and another; it does not do to regard strangers as friends.

I had, indeed, later on, abundant evidence that caution in such respects was needed. At a little settlement called Kunajuk, on the Ellice River, I questioned each of the men as to whether they had taken part in or been subject to acts of violence. The results are set out as follows: and it should be noted that in nearly every case the victims were of the same tribe; the motive was invariably some quarrel about a woman.

Angulalik had taken part in a murderous affray but had not himself killed any one.

Uakuaq had killed Kutdlaq in revenge for the latter's killing of Qaitsaq.

Angnernaq had two wives. One had been stolen away from him, but he had not yet taken vengeance.

Portoq had carried off the wife of a man who had not yet taken vengeance.

Kivggaluk had lost his father and brother—both murdered.

Ingoreq had attempted to murder twomen, but failed.

Erfana had killed Kununassuaq, and taken part in the killing of Kutdlaq.

Kingmerut had killed Maggararaq and had also taken part in a murderous attack upon another man.

Erqulik stated that two attempts had been made to carry off his wife, both without success.

Pangnaq, a boy of twelve, had shot his father for ill-treating his mother.

Maneraitsiaq had shot a man in a duel (with bow and arrow) but had not killed him.

Tumaujoq had killed Ailanaluk in revenge for the murder of Mahik.

One may often hear people who know nothing of the life of "savage" tribes suggest that these should be left to live in their own way and not have civilization forced upon them. My own experiences in these particular regions have convinced me that the white man, though bringing certain perils in his train does nevertheless introduce a gentler code, and in many ways lightens the struggle for existence.

On the other hand, one must not judge these children of nature too harshly. They are, in fact, still in but an early stage of evolution as human beings. And we should bear in mind that life in these inhospitable regions, exposed to the cruelest conditions and ever on the verge of extermination is not conducive to excessive gentleness.

- ↑ In contrast to the Caribou Eskimos and the natives of the Hudson Bay district, the Netsilingmiut prounounce the letter "s" distinctly, as is evident from their songs and their names. Among the other tribes, the sound of "s" is not found, "j" or "h" being used instead.

- ↑ This is the Eskimo view. Actually, it is the land which has risen.