Across Arctic America/Chapter 17

Chapter XVII

Belated Honors

By the end of September we were ready to start sledging again. A week sufficed to procure the caribou meat needed for our stay and for the journey. We had built two light sledges of the Greenland type, with iron runners, for this autumn work, as the long Hudson Bay sledges with peat-and-ice shoeing would be useless on the soppy new ice of the autumn, when there is no snow. The work was soon done, and we were now only waiting for the ice to come. We were, to tell the truth, impatient to make a start on this new stage of our journey, which should, in the course of the spring, carry us into civilized regions once more. Meantime, we occupied ourselves with short excursions in the neighborhood. I had by this time completed my work as far as the folklore department was concerned, and was able now to turn my attention to a project I had long had in mind, and which, I am happy to say, proved successful.

It was, as many of my readers are doubtless aware, in the region of King William's Land that one of the greatest tragedies in the whole history of Arctic exploration took place. In the year 1845, John Franklin sailed from England with two fine ships, the Erebus and the Terror, with crews totalling 129 officers and men. The object of the expedition was to find and traverse the North-west Passage, the great sea-route then supposed to connect the Atlantic with the Pacific. But instead of an open channel, they found only straits and sounds blocked with heavy ice. After one winter spent under these conditions, the ship was beset, and had to be abandoned; and an attempt to find a way back to civilization via the Great Fish River resulted in the death, after terrible sufferings, of all those who had not previously perished of disease. Numerous relief and search expeditions were sent out, but it was many years before definite information was obtained, through the Netsilingmiut themselves, as to the fate of the unfortunate explorers.

I have already mentioned meeting, while at Pelly Bay, a native named Iggiararsuk, whose parents had come in contact with members of the Franklin Expedition. And now, here at Malerualik again, I found that several of the older men were able to communicate interesting details as to what had taken place on that occasion. I made careful notes of all they had to say; the account given below is in the words of Qaqortingneq himself. One feature common to all the accounts, which struck me as curious at the time, was the comparative indifference of the narrators to the tragic element in the story; the point that seemed to interest them most was the ignorance that prevailed in those days among their own people as to white men generally, and their goods and gear in particular as viewed in the light of the narrators' own superior knowledge. This was drawn upon to the utmost as a source of comic relief. I have here omitted the numerous Eskimo names, for the sake of brevity: Qaqortingneq always insisted on giving the names of all concerned, as evidence that his story was to be relied on.

Qaqortingneq's account, then, is as follows:

"Two brothers were out hunting seal to the northwest of Qeqertaq (King William's Land). It was in the spring, at the time when the snow melts about the breathing holes of the seal. They caught sight of something far out on the ice; a great black mass of something, that could not be any animal they knew. They studied it and made out at last that it was a great ship. Running home at once, they told their fellows, and on the following day all went out to see. They saw no men about the ship; it was deserted; and they therefore decided to take from it all they could find for themselves. But none of them had ever before met with white men, and they had no knowledge as to the use of all the things they found.

"One man, seeing a boat that hung out over the side of the ship, cried: 'Here is a fine big trough that will do for meat! I will have this!' He had never seen a boat before, and did not know what it was. And he cut the ropes that held it up, and the boat crashed down endways on to the ice and was smashed.

"They found guns, also, on the ship, and not knowing what was the right use of these things, they broke away the barrels and used the metal for harpoon heads. So ignorant were they indeed, in the matter of guns and belonging to guns, that on finding some percussion caps, such as were used in those days, they took them for tiny thimbles, and really believed that there were dwarfs among the white folk, little people who could use percussion caps for thimbles.

"At first they were afraid to go down into the lower part of the ship, but after a while they grew bolder, and ventured also into the houses underneath. Here they found many dead men, lying in the sleeping places there; all dead. And at last they went down also into a great dark space in the middle of the ship. It was quite dark down there and they could not see. But they soon found tools and set to work and cut a window in the side. But here those foolish ones, knowing nothing of the white men's things, cut a hole in the side of the ship below the water line, so that the water came pouring in, and the ship sank. It sank to the bottom with all the costly things; nearly all that they had found was lost again at once.

"But in the same year, later on in the spring, three men were on their way from Qeqertaq to the southward, going to hunt caribou calves. And they found a boat with the dead bodies of six men. There were knives and guns in the boat, and much food also, so the men must have died of disease.

"There are many places in our country here where bones of these white men may still be found. I myself have been to Qavdlunarsiorfik [a spit of land on Adelaide Peninsula, nearly opposite the site where Amundsen wintered]; we used to go there to dig for lead and bits of iron. And then there is Kangerarfigdluk, quite close here, a little way along the coast to the west.

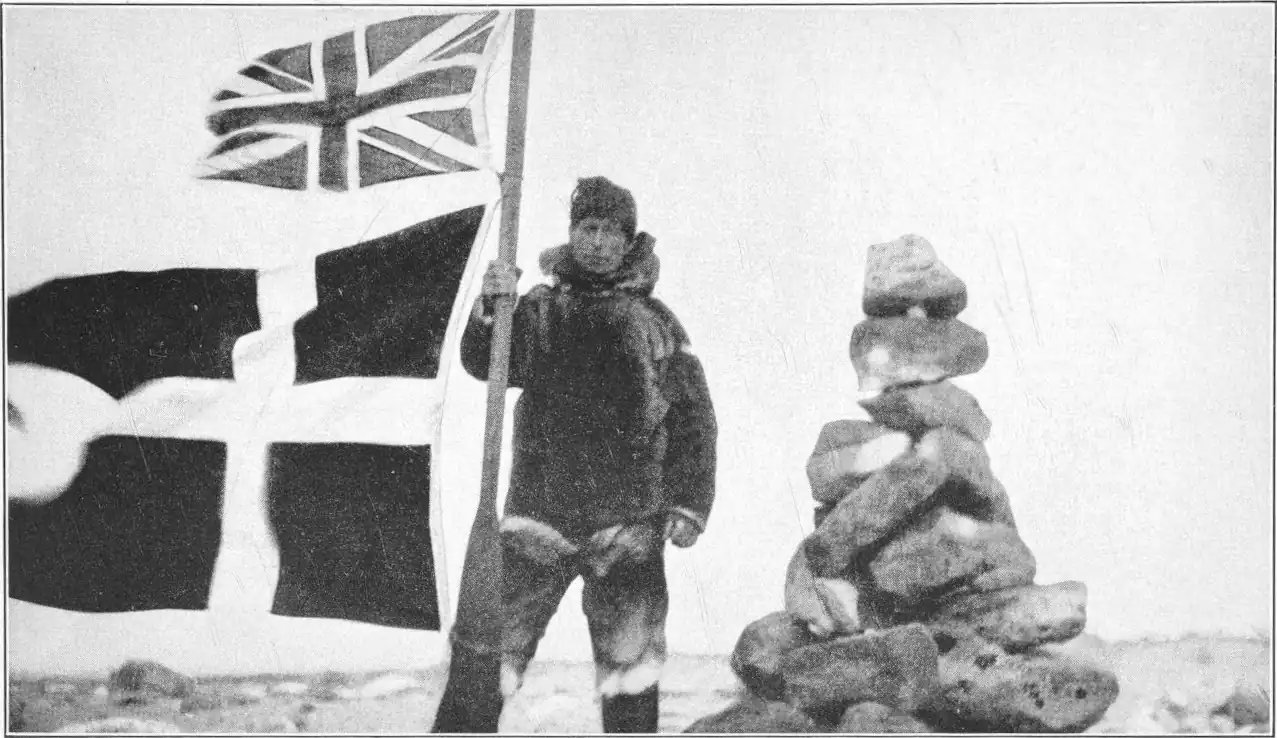

One day just before the ice had formed, I sailed up with Peter Norberg and Qaqortingneq to Qavdlunarsiorfik, on the east coast of Adelaide Peninsula. And here, exactly in the spot indicated by the Eskimos, we found a number of human bones, unquestionably the last mortal remains of Franklin's men. Some scraps of clothing and footwear scattered about the same spot showed that they were those of white men.

We gathered the poor remains together and built a cairn above them, hoisting two flags at half mast above; their own and ours. And without many words we paid the last honors to the dead.

Here on this lonely spit of land, weary men had toiled along the last stage of their mortal journey. Their tracks are not effaced, as long as others live to follow and carry them farther; their work lives as long as any region of the globe remains for men to find and conquer.

Our first encounter with a fellow human here was not exactly cordial to begin with, but characteristic of these people in their normal relations with other tribes. I was out reconnoitring, when I caught sight of a young man fishing for cod through a hole in the ice. The moment he sighted me, he snatched up his line and scuttled off to the shelter of a rock, whence he presently reappeared with a fine new magazine rifle of the lastest model, evidently ready to make short work of me at the slightest sign of danger. It did not take long, however, to convince him of my complete friendliness as far as he was concerned, and we were soon laughing heartily at the misunderstanding. And he took me along to his village and introduced me almost as if we had known each other for years. From the appearance of the hut and its furnishings it was plain that we were not far from a trading station. Fine woollen blankets of the Hudson's Bay Company's best were spread about among caribou skins more suited to the climate; enamelled ironware had taken the place of the carved and blubber-polished vessels made from driftwood; there were aluminium cooking pots instead of the heavy stone utensils, and even the soapstone lamp, a handsome article in itself, was here replaced by a glittering tin contrivance out of a shop.

On the sleeping place sat a young woman cross-legged, her magnificent caribou furs partly covered and utterly effaced by a horrible print apron. Her hands were covered with cheap-jack rings, a cheap cigarette was held between two fingers, and she breathed out smoke from her nostrils as she leaned back with the languid insolence of a film star and greeted us with a careless "how do you do."

I thanked my lucky stars at that moment that I had visited King William's Land at least before the trading stations had got hold of it; while there was still some native life and folklore left to explore.