Across Arctic America/Chapter 2

Chapter II

Takornaoq Entertains Gentlemen Friends

In the middle of a big lake an old Eskimo woman stood fishing for trout. In spite of the fact that the winter was yet young the ice had already become so thick that all her strength must have been needed in cutting the hole for her line. Now and then she took a piece of drift-wood shaped like a shovel and pushed away the fragments of ice that were in her way. Then stretching out on her stomach she thrust half her body so far into the hole that all that remained visible was a pair of bent, skin-covered legs waving in the air.

Suddenly a puppy that had lain buried in the snow scrambled to his feet and started to bark wildly. Tumbling out of the hole, the old woman crouched, bewildered at seeing Bosun and myself so near her. At full speed our dogs dashed down on the odd pair.

Uttering a sharp cry, she seized the pup by the scruff of the neck and set out in the direction of the village as fast as her ancient legs would carry her. The panic of her flight only served to increase the wildness of our dogs, already excited by the scent of the village, and such was their speed that, in passing the fugitive, I had barely time to seize her and fling her on top of the flying sledge. There she lay with horror in her eyes, while I burst out laughing at the absurdity of the scene. At length, through her tears of fright, she started to smile, too, realizing that I was a human, and a friendly human being, at that.

It was old Takornaoq. She now sat with arms convulsively clutching the whimpering pup. Then above the noise of the frightened dog I suddenly heard a sound that startled me in turn. Bending over her and cautiously lifting her skin kolitah I discovered far down inside her peltry clothing a small infant clinging to her naked back and whimpering in unison with the mother and the terrified puppy.

Such was my meeting with Takornaoq. Soon we were friends. We raced merrily along to her village, which consisted of three snow huts. Here we were introduced to the notables of the place.

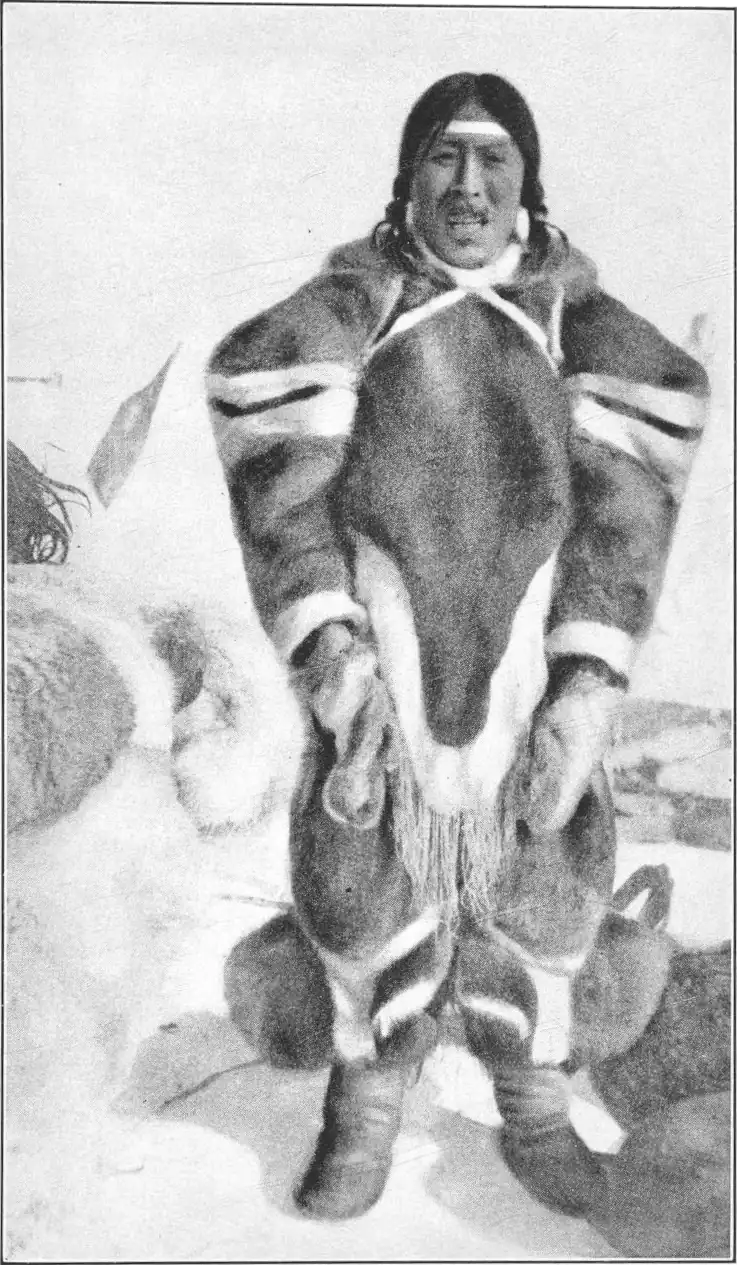

Inernerunassuaq was an old angakoq, or wizard, from the neighborhood of the Magnetic Pole. He screwed up his eyes to a couple of slits on being introduced, and was careful to draw my attention to his magic belt, which was hung about with zoological preparations. His wife was a simple soul, fat and comfortable, as befits one married to a specialist in the secret arts. They had a large family of small children who hung about getting in the way; none of them had reached the age when a child is reckoned worthy of a name, and their parents simply pointed at this one or that when telling them to be quiet.

Then there was Talerortalik, son-in-law to the foregoing, having married Uvtukitsoq, the wizard's daughter. They looked an insignificant pair; but we found out afterwards that it was they who made ends meet for the wizard and his flock. Finally, there was Peqingassoq, the cripple, who was said to be specially clever at catching trout. Others were briefly introduced, and Takornaoq carried me off to her own hut. It was clean and decent as such places go, but chilly, until we got the blubber lamp well alight.

Bosun and I settled down comfortably on the sleeping place among the cosy caribou skins. And as soon as the meat was put on to boil, Takornaoq sat down between us with the unexpected observation that she was "married to both of us now," her husband, whom she loved, being away on a journey. Then taking a tiny infant from her amaut, she laid it proudly in a hareskin bag. The child was named Qasitsoq, after a mountain spirit, the mother explained. It was not her own child, but one of twins born to a certain Nagsuk; she had bought it for a dog and a frying pan. It was too much really, for such a pitiful little creature, nothing but skin and bone; Takornaoq complained bitterly that Nagsuk had cheated, and given her the poorer of the two.

Our hostess told us a great deal about herself and her family. She was of the Igdlulik, from Fury and Hecla Strait, a tribe noted for clever hunters and good women; and she was proud of her origin, as being superior to that of her fellow-villagers here. Our visit was most welcome, she assured us, and even went to the length of voicing her appreciation in an improvised song, which she delivered sitting between us on the bench. Her voice, it is true, was somewhat over-mellowed by her sixty odd winters, but its quavering earnestness fitted the kindly, frank, simplicity of the words:

Immediately after the song, dinner was served. Our hostess, however, did not join us at the meal; a sacrifice enjoined by consideration for the welfare of the child. Among her tribe, it appeared, women with infant children were not allowed to share cooking utensils with others, but had their own, which were kept strictly apart.

Not content with feeding us, however, she then opened a small storehouse at the side of the hut, and dragged forth the whole carcase of a caribou. This, the good old soul explained, was for our dogs. And with rare tact, she tried to make the gift appear as a matter of course. "It is only what my husband would do if he were at home. Take it, and feed them." And she smiled at us with her honest old eyes as if really glad to be of use.

Bosun and I agreed that it was the first time in our lives a woman had given us food for our dogs.

We enquired politely after her husband, Patdloq, and learned that she had been married several times before. One of her former husbands, a certain Quivapik, was a wizard of great reputation, and a notable fighter. On one occasion, at Southampton Island, he was struck by a harpoon in the eye, while another pierced his thigh. "But he was so great a wizard that he did not die of it after all." He was an expert at finding lost property, and had a recipe of his own for catching fish.

"Once we were out fishing for salmon, but I caught nothing. Then came Quivapik and taking the line from me, swallowed it himself, hook and all, and pulled it out through his navel. After that I caught plenty."

Another of Takornaoq's adventures shows something of the dreadful reality of life in these regions.

"I once met a woman who saved her own life by eating her husband and her children.

"My husband and I were on a journey from Igdlulik to Ponds Inlet. On the way he had a dream; in which it seemed that a friend of his was being eaten by his own kin. Two days after, we came to a spot where strange sounds hovered in the air. At first we could not make out what it was, but coming nearer it was like the ghost of words; as it were one trying to speak without a voice. And at last it said:

"'I am one who can no longer live among humankind, for I have eaten my own kin.'

"We could hear now that it was a woman. And we looked at each other, and spoke in a whisper,

"'Kikaq' (a gnawed bone) she said, 'I have eaten my husband and my children!'

"She was but skin and bone herself, and seemed to have no life in her. And she was almost naked, having eaten most of her clothing. My husband bent down over her, and she said:

"'I have eaten him who was your comrade when he lived.'

"And my husband answered: 'You had the will to live, and so you are still alive.'

"Then we put up our tent close by, cutting off a piece of the fore-curtain to make a shelter for the woman; for she was unclean, and might not be in the same tent with us. And we gave her frozen caribou meat to eat, but when she had eaten a mouthful or so, she fell to trembling all over, and could eat no more.

"We ceased from our journey then, and turned back to Igdlulik, taking her with us, for she had a brother there. She is still alive to this day and married to a great hunter, named Igtussarssua, and she is his favorite wife, though he had one before.

"But that is the most terrible thing I have known in all my life."