Across Arctic America/Chapter 20

Chapter XX

The Battle with Evil

I had now enough material for a whole monograph on the Musk Ox People. There were the four main sections: the Willow-folk or Caribou Eskimo, the Hudson Bay tribes, the Netsilingmiut or Seal Eskimo, and now the Musk Ox People. It remained to procure supplementary material from the western tribes of the Mackenzie Delta, Alaska, Bering Straits and Siberia. The country between—that is, the coast from Bathurst Inlet to Baillie Island—had been visited and described by Stefansson's Expedition during his first visit to these regions, and later by Dr. Diamond Jenness, Ethnographer to Stefansson's last Expedition, the so-called Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913-18. Few have understood the Eskimo so well as Stefansson, or had the power of living their life and entering into their way of thought; and no modern writer has given a more thorough and detailed description of an Eskimo tribe than Jenness. I could therefore with an easy conscience pass lightly over this section.

From my last field of work to the next was a distance of something like 2200 kilometres, which had to be covered as rapidly as possible, though at the same time I should have to make halts on the way,

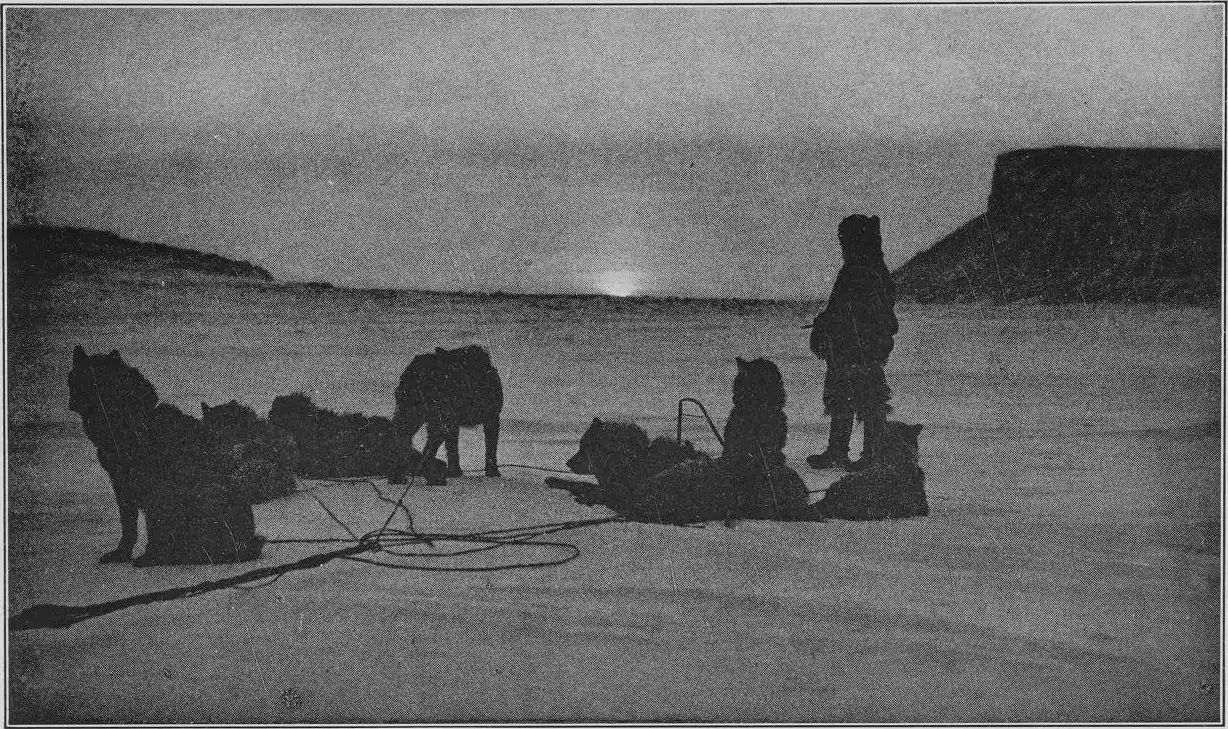

We divided the dogs into two teams, small teams they were, considering our load. I and Anarulunguaq had to make do with six of the best animals, taking, however, the smaller of the two sledges, and a comparatively light load, of some 300 kilos. Miteq had ten dogs, and was to drive Leo Hansen with his camera and other impedimenta, their load amounting I should say to something approaching 500 kilos. Thanks to the invaluable method of ice-shoeing, however, we were able from the first to travel at a fine smart pace, which brought us through well up to time.

We started in a smother of snow, that drove right in our faces, with the thermometer at minus 42. Our first objective was Malerisiorfik, where we had to pick up some of our effects left there from our previous visit. Here we were stormbound, but managed to get away on the 18th of January, though it was still snowing hard. On the 21st we rounded Cape Barrow, and after following the coast—low granite rock for the most part—for a few hours, we shaped our course for a high, steep promontory some distance ahead. Before we reached it, however, a fog came down and we were beginning to feel thoroughly lost, when the dogs got scent of something, and about three o'clock we drove into a village out on the ice, and were received with great friendliness. The place, we were informed, was called Agiaq, and the people styled themselves Agiarmiut; there were 46 of them in all, 25 men and 21 women.

Our recent experiences had led us to adopt a certain reserve as a protection against the exuberance of the native welcome; here, however, we were pleasantly surprised to find our hosts quiet and modest almost to the verge of shyness. We found a snowdrift close handy, and managed, with their help, to get a hut built just in time, for it was growing dark, and there was a blizzard coming up. It came; and kept us hung up there from the afternoon of the 22nd until the 26th. All that time we were literally imprisoned in our snow hut, which threatened every now and them to fall to pieces or be torn away by the gale, as the snow from which it was made had been too soft to start with, but we had not had time to pick and choose. We had to dash out every now and then to patch up a threatened spot, and it was no easy matter in such a storm. The blocks we cut crumbled between our fingers.

During these four days, anyone who came to visit us had to come armed with a snow knife in case of getting lost; it was only a matter of five minutes from their huts to ours, but all the same, a man might go to his death. Despite the risk, we had a constant stream of visitors, men, women and children, including infants in arms, or in the amaut that answers to it. And I found myself once more admiring the manner in which these people adapt themselves to their surroundings. Just fancy—you go off to visit a friend who lives five minutes' walk from your door. If you lose your way it is death; unless you have your snow knife, which of course you are not foolish enough to leave behind. Armed with this, you have only to build yourself another little house by the roadside, and here you can settle down in safety, if not in comfort, until the weather clears. People at home might think it a troublesome way of going visiting; but here it is considered all in the day's work, or the day's play, and all adds to the excitement of the visit.

On the third evening we were formally invited to a spirit seance in one of the huts. The invitation was issued by one Kingiuna, a typical blond Eskimo, with a bald head, reddish beard, and a touch of blue about the eyes. We were given to understand that the stormchild, Narsuk, was angry, and it was proposed to ascertain if possible what had been done to offend him, with a view to propitiation, that the storm might be called off.

It took us something like half an hour, I really believe, to cover the half kilometre we had to go, so fierce was the storm. When at last we arrived, we found ourselves in a snow hut some 4 metres by 6, but so high that the roof had to be supported by two long pieces of driftwood, that looked most imposing as black pillars in this white hall. There was ample room for all; and the children, who had been brought along by their respective parents, played hide and seek round the pillars while the preparations were being made.

These preparations consisted mainly of a banquet, the menu comprising dried salmon, blubber, and frozen seal meat, the last served up, not in joints, but in whole carcases, from which slabs were cut with axes. This frozen meat has to be breathed on at every mouthful, to take the chill off; otherwise it is apt to take the skin off one's lips and tongue.

"Fond of eating, these people," whispered Miteq, with his mouth full of frozen blood, "stand anything; and make great festivals anywhere."

And indeed it needed a good digestion to tackle the food, as it needed cheerful courage to feast under such conditions.

The officiating angakoq was one Horqarnaq, a young man with bright, intelligent eyes and little hasty movements. He looked the picture of honesty; and it was perhaps on that account that it took him so long to get into a trance. Before starting, he explained to me that he had not many helping spirits. There was the ghost of his dead father, with his helping spirit, a kind of ogre out of the stories, a giant with claws that could shear through a human body; then there was a figure he had carved for himself out of soft snow, in the shape of a human being; this spirit always came at his call. A fourth mysterious helper was a red stone called Aupilalanguaq, which he had found once when out caribou hunting; it looked exactly like a head and neck together, and when he shot a caribou close by, he made a necklace for it from the long hairs of the caribou's neck. In this way he made his helping spirit an angakoq itself, and thus doubled its power.

These were the spirits he was now about to invoke. And he began by declaring very modestly that he knew he could never do it. The women stood round encouraging him with easy assurance.

"Oh, yes you can; it's easy for you because you are so strong."

But he went on repeating the same thing: "It is difficult to speak the truth; it is a hard thing to call forth the hidden powers."

For a long time matters remained like this, but at last he began to show signs of the approaching trance. Then the men joined the circle, pressing in closer around him, and all shouted encouragement, praising his strength and spiritual powers.

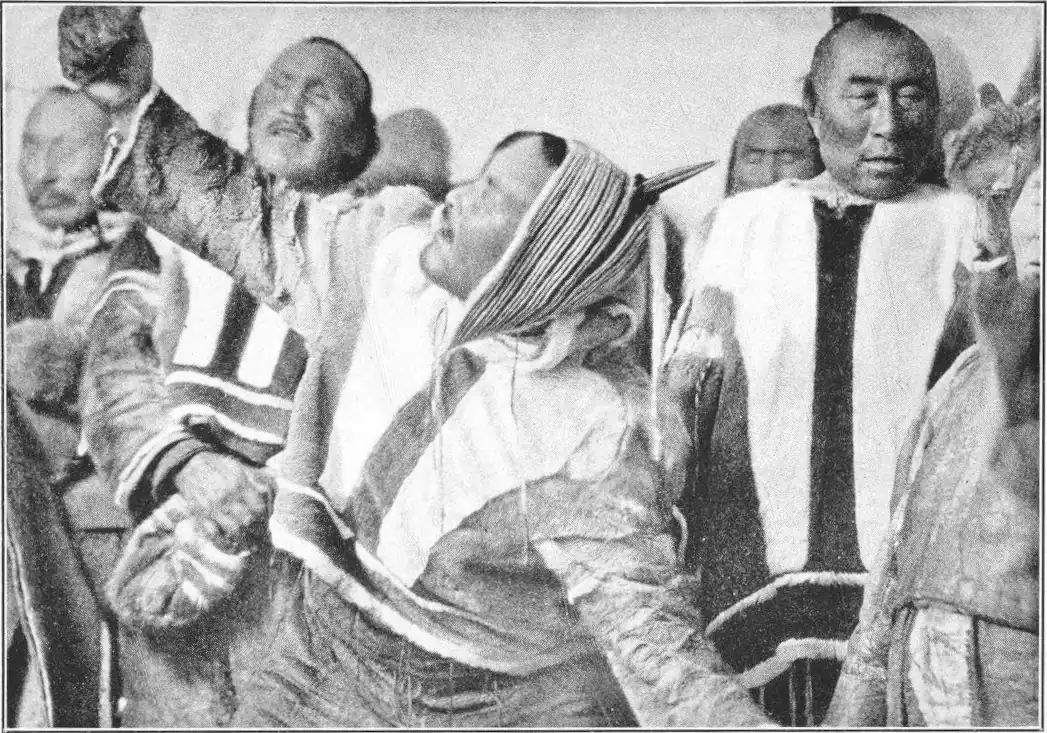

The wizard's face is strained, his eyes are wide open, as if staring out into a vast distance; now and again he swings round on his heels, and his breath comes in little jerky gasps. He seems hardly to recognize those about him.

"Who are you?" he cries.

"We are your own people."

"Are you all here?"

"Yes; all but those two who have gone on a journey to the eastward."

But he does not seem to hear, and asks again and again:

"Who are you? Are you all here?"

Then suddenly he fixes his gaze upon Miteq and myself, and he cries:

"Who are the strangers?"

"They are men travelling round the earth; men we are glad to see. They are friends; and they too would gladly hear what wisdom you can give us."

Again he goes round the circle, looking into the eyes of each as he passes, they stare wildly around, and at last, in the despairing voice of one who can do no more, he cries, "I cannot, I cannot!"

Then comes a gurgling sound, interpreted as meaning that a helping spirit has taken possession of his body. He is now no longer master of himself, but dances about among the rest, calling on his dead father who is become an evil spirit. It is only a year since his father died, and the widow, who is present, groans aloud and endeavors to comfort her son in his frenzy, but the rest will not have it; he is to go on, go on, and let the spirit speak.

He then mentions several spirits of the dead, that he sees before him among the living audience. He describes their appearance, this old man and that old woman whom he himself has never seen, and calls on those present to say who they are.

The audience are at a loss; there is a moment of silence, then a whispering among the women; one mentions hesitatingly this name or that.

"No, no, that is not right."

The men look on in silence, the women growing more excited, all save the widow, who sits weeping and rocking from side to side. Then suddenly an old woman who had been silent up to now, jumps up and utters the names that none as yet have dared to mention; a man and a woman from Nagjugtoq, who died quite recently.

"Qanorme."

"Qanorme!"

"They are the ones," cries Horqarnaq in a strange gasping voice, and a feeling of dread takes possession of all at the thought of those now spirits who but a few days before were living and moving among them in the flesh. And to think it was they who were causing the storm. The terror spread through the house; the mystery of life hung heavy upon all; here were happenings beyond their understanding.

Outside the storm was raging in black darkness, and even the dogs, who are not allowed inside the houses as a rule, are suffered now to seek shelter and warmth. A man and a woman, who live next door, but had lost their way, come in with mouths and eyes choked with snow. It is the third day of the storm. They have no meat for tomorrow, no fuel; and the threatening disaster seems all at once nearer and more real. The storm child is wailing, the women are moaning, the men murmur incomprehensible words.

After about an hour of shouting and invocation of unknown forces, the seance takes a new turn. To us, who have not previously assisted at a taming of the storm-god, the next development is horrible to see. Horqarnaq leaps out and flings himself upon poor inoffensive old Kingiuna, who was singing a little hymn on his own account, grabs him by the throat with a swift snatching movement, and flings him backward and forward among the rest. This goes on for some time; with hoarse gasps from both men at first; but after a while Kingiuna chokes, and can utter no sound save a faint wheezing; then all in a moment he too seems to fall into a trance. He makes no resistance now, but suffers himself to be swung this way and that; Horqarnaq drags him about the place, heedless of any risk to themselves or the rest. Some of the men place themselves in front of the lamps, to guard against accidents, the women drag their children up out of the way—and so the ghastly play goes on, until Horqarnaq, himself exhausted, or satisfied that he has done enough, drops his victim in a heap on the floor.

Thus the wizard battles with the spirit of the storm—a fellow-man being made to represent it. Finally, he stoops down over the still unconscious Kingiuna, and fixing his teeth in his neck, shakes him viciously, as a dog shakes another beaten in fight.

Then he continues his wild capers, the rest looking on in silence, until at last the frenzy seems to die out, and he kneels down beside his victim stroking the body to bring it back to life. Slowly the other awakens, and rises unsteadily to his feet, but he is hardly up before the wizard is upon him once more, and the whole dreadful business is repeated until Kingiuna again lies helpless and insensible as before. Yet a third time he is "killed" in this horrible mummery; that man's mastery of the elements may be established beyond question. But when he comes to life for the third time, it is Horqarnaq who collapses, and Kingiuna now takes the active part. The old fellow, with his unwieldly bulk, seems unfitted for anything but a comic part, yet the wild. fierce look in his eyes, and the horrid bluish tinge that has not yet faded from his face, are impressive enough; he looks like one dragged back from the clutches of death. All step back involuntarily as with his foot on Horqarnaq's chest he tells what he sees. With fluent speech and a voice quivering with emotions he begins:

"The heavens are full of naked beings rushing through the air. Naked men and women, rushing along and raising the storm, raising the blizzard.

"You hear it? A rushing as of the wings of mighty birds, up in the air. It is the fear of naked beings, the flight of naked men.

"The spirit of the air drives forth the storm, the spirit sends the whirling snow out over the earth, and the helpless storm-child, Narsuk, shakes the lungs of the air with its weeping.

"Hear the crying of the child in the shrieking of the storm!

"And see now—there among the hosts of naked ones in flight is one, a single figure, a man pierced all into holes by the wind. His body is but a mass of holes, and the wind howls through them—Tchee-u-u-u; tchee-u-u-u. Hear! He is the mightiest of them all.

"But my helping spirit shall bring him to a stand; bring all to a stand. Here he comes, striding down sure of victory towards me. He will conquer, he will conquer—Tchee-u-u-u, Tchee-u! Hark to the wind! Hist! hst, hst! See the spirits, the storm, the wild weather, rushing by above us, with a sound as the wings of mighty birds!"

At these words Horqarnaq gets up from the floor, and the two wizards, their faces now transfigured after what has passed, join in a simple hymn to the Mother of the Sea:

As soon as the two had sung it once, all present joined in a wailing, imploring chorus; they had no idea of what they were praying to, but they felt the power of the ancient words their fathers had sung. They had no food to give their children on the morrow; and they prayed the powers to make a truce for their hunting, to send them food for their children.

And so great was the suggestive power of what had passed, in this wild place too near to the elemental forces, that we could almost see it all; the air alive with hurrying spirit forms, the race of the storm across the sky, hosts of the dead whirled past in the whirling snow; wild visions attended by that same rushing of mighty wings of which the wizards had spoken.

So ended this battle with the storm; a contest between the spirit of man and the forces of nature. And those present could go home and sleep in peace, confident that the morrow would be fine.

And in point of fact, so it proved. Through dazzling sunlight over firmly packed snow we drove off on the following day, arriving in the afternoon at Tree River, where there is a station of the Hudson's Bay Company and a police post of the C. M. P. We were very kindly received by the Company's representative, Mr. MacGregor, with whom we stayed for two days.

Five people had been murdered near Kent Peninsula, the original cause of the trouble being that one of the attacking party wanted to steal another's wife, who, however, was killed in the struggle, together with her husband, the defenders making so stout a resistance, that the assailants found themselves at the finish fighting for their lives. Among them were two young men one Alekamiaq, only 16 or 17 years old, the other, Tatamerana, but little older. They were captured by the police, but Alekamiaq managed to shoot the corporal who arrested him, together with a trader living near. Before he could escape however, two sledges from a neighboring settlement came up; and he was taken off at once to Herschel Island, the chief police post of the district. Here he and Tatamerana lived for a couple of years, acting as a kind of servants to the police, while they were waiting to be tried. They were allowed to move about freely among the other natives and the white men; no one felt any fear of them; they were indeed rather liked in the place.

It was a lengthy and difficult business to get the two murderers hanged. Judges, advocates, and witnesses had to be brought from a long distance. The murder of the two white men took place in 1922 and it was not until last winter—in February if I remember rightly—that the murderers were hanged.

The trial with its ceremonial made no great impression on them; they seemed to have an easy conscience in the matter. Both men were condemned to death; but the sentence had first to be confirmed by the supreme authority in Canada. At last one evening, when they were busy making salmon nets, they were informed that they were to be hanged at three the next morning. Young Alekamiaq received the information with a smile; Tatamerana asked huskily for a glass of water, but as soon as he had drunk it he was himself again, and ready to meet his fate. Just before going to execution, they gave the Police Inspector's wife some little carvings of walrus tusk, as souvenirs, to show they bore no ill will against the police. Both met their death calmly and without sign of fear.

I was informed that this execution had cost Canada something like $100,000; among other expensive items being the cost of the executioner, who had to be brought up and kept there all the winter, as none of the Police themselves would have any hand in this part of the work.

One of the two criminals had an old father living at Kent Peninsula, who, learning that his son was to be sent to the eternal hunting grounds, decided that he could not let him go alone. And after three attempts, he managed to kill himself, fulfilling what he conceived to be his duty to his son.