Across Arctic America/Chapter 21

Chapter XXI

Among the Blond Eskimos

On the 28th of January we left our kindly hosts at Tree River and crossed over Coronation Gulf to Cape Krusenstern. The wind was like cold steel, and the snow drove right in our faces. It is costly travelling on a day like this, as one cannot avoid getting frost sores in the face, and these are a constant source of trouble and annoyance throughout the rest of the winter. We reached Cape Krusenstern on the 30th after a struggle with pressure ridges and fantastic barriers of ice, through all of which to our surprise, the ice shoeing held. The natives here came literally tumbling over us, in the most unceremonious fashion; some of them scrambled up on to our sledges, and I was amused to see them sitting there with their harpoons, looking like halberdiers on guard. They somehow got the idea that Leo Hansen was a very great personage whom we were escorting into the white men's country, and as we approached their village, the ones who had met us first shouted out without the least reserve the most amusing remarks about ourselves, telling the others to come and look at the new sort of travellers they had found. They must be something very odd, for they did not appear to be either traders or police! It never seemed to occur to them that we could understand what they said, and they commented frankly on my big nose and Anarulunguaq's fat cheeks. Our dresses, appearance and equipment were criticized in like fashion, exactly as if we were a travelling circus making entry into some village miles from anywhere.

I stood it for a while, and then gave them, briefly but pithily, my own opinion of their manners, appearance and order of intelligence, more particularly their simplicity in taking it for granted that we could not understand them. There was a moment of dead silence when I had finished; all stared at us with eyes and mouths agape, then gave vent to a howl of laughter. They were not accustomed to meeting white men who understood their language. But the mistake left no ill-feeling; on the contrary, we were friends at once. We stayed here a day, and I went through my regular list of questions, which, from long practice, enabled me to get quite a lot of information, while Leo Hansen was busy with his pictures.

On the 1st of February we arrived at Bernhard Harbour, where the Hudson's Bay Company has a station. Their representative here proved to be a fellow-countryman of mine, Peder Pedersen, of Loegstoer, who had left Denmark 42 years before and spent about a generation in the Arctic. He received us with the greatest cordiality, and though he spoke Danish with some hesitation at first, it was not long before it all came back to him.

We were now anxious to get through to the

Bernard Harbor was at one time the headquarters of the Canadian Arctic Expedition under the capable leadership of Dr. Martin Anderson. I could therefore with an easy conscience deal summarily with this district, as ethnographical studies had already been systematically carried out by my predecessors. I contented myself therefore with going through the afore-mentioned list of questions, which gave me all I needed for comparison with my notes from elsewhere. We then hurried out to a big hunting camp near Sutton and Liston Island, which the Eskimos call Ukatdlit, in Dolphin and Union Strait. I stayed here a week and brought my journals up to date.

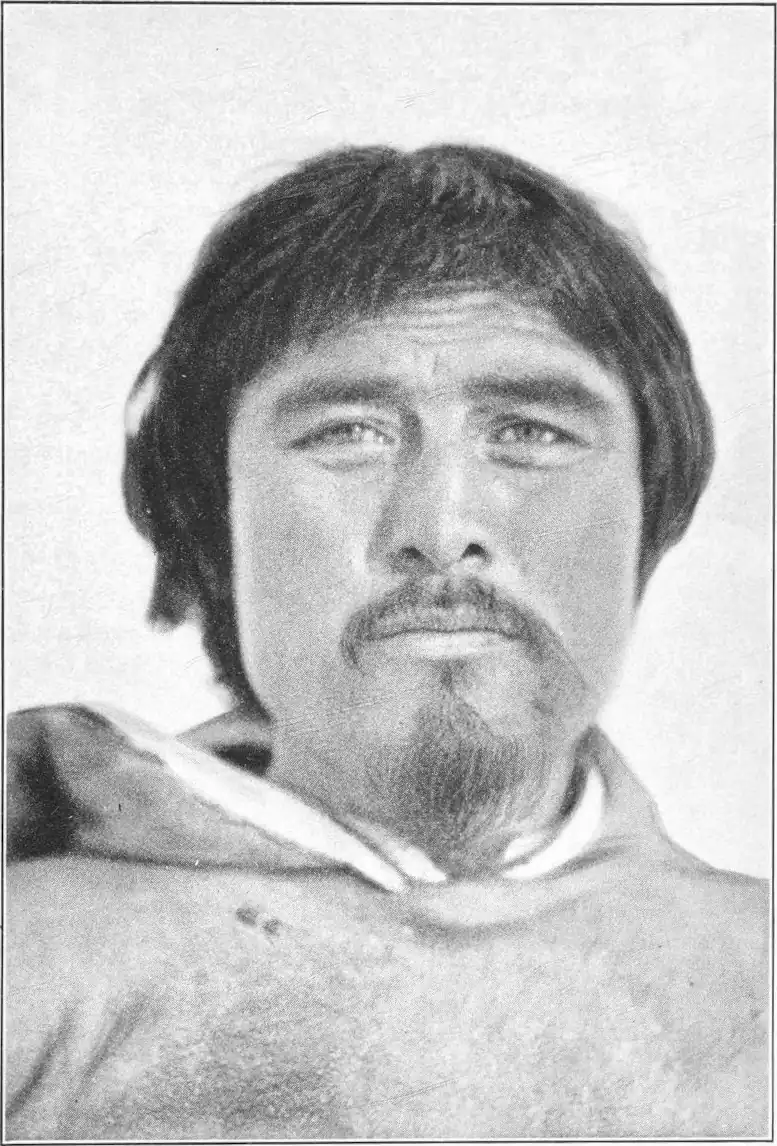

The Eskimos of these regions, like those farther east, have no regular chiefs, but each settlement has one man who acts as a sort of general adviser and leader in common undertakings. The leading man here was Ikpakhuhak, who, with his jovial wife Hikilaq, is described at length in Diamond Jenness' excellent work The Life of the Copper Eskimos.

The encampment consisted of twenty large and roomy snow huts, and was built near a small island called Ahongahungaoq, whence the people called themselves Ahongahungarmiut; they numbered 83 souls, of which 46 were men and 37 women; a considerable population for one village in these regions. Most of them were from Victoria Land where they had lived until recently under the name of Puivdlermiut, but owing to the gradual thinning out of the game in those parts, they had moved across to the mainland, hunting the territory between Great Bear Lake and the coast north of Stapylton Bay. My actual hosts belonged to this contingent; but there were also representatives of the original mainland tribes, and others again from Prince Albert Sound and Minto Inlet, so that I had here an excellent opportunity of collecting information from a considerable area at one spot, and was saved the necessity of visiting Prince Albert Sound.

The camp here, at Dolphin and Union Strait, marks the boundary of the so-called eastern Eskimos, the whole range of country between Inman River and Baillie Island being inhabited only by trappers or immigrant Eskimos from Alaska. At Baillie Island we have the beginning of an entirely new Eskimo culture, closely associated with hunting by sea, and consequently superior in material respects, while the natives to the eastward are still only in the initial stages of development to the coastal form, and are in fact very nearly allied to the Caribou Eskimos.

Nearly all movement among the Eskimos of the North-west Passage seems as far as tradition serves, to have run in an easterly direction, and occasionally by certain definite routes to the southward, where the diffierent tribes exchanged needful commodities. There is no record of any journeys to the west, toward Cape Bathurst, and all that was known about the country on the west was that it were said to be inhabited. The whole of the area here described had a special source of wealth in the deposits of pure copper, which are found at Bathurst Inlet and in parts of Victoria Land, especially Prince Albert Sound. This copper was used for making knives, ice-picks and harpoonheads, which were of great value when trading with other tribes. Diamond Jenness has therefore rightly grouped all these tribes under the name of Copper Eskimos.

These are the same people who suddenly sprang into fame some years back as the "blond Eskimos." They were discovered in 1905 by a Danish adventurer named Klinkenberg, who, setting out from Herschel Island in a small schooner, was driven out of his course and landed at a spot which later proved to be Minto Inlet. On his return, he told of a strange people he had met, who spoke the Eskimo tongue and lived in the Eskimo fashion, but in appearance looked exactly like Scandinavians. Klinkenberg's report led Vilhjalmur Stefansson, with the zoologist Dr. Martin Anderson, to set out on a new expedition, lasting from 1908-12, and described in his book My Life with the Eskimos.

In the year 1910 Stefansson had his headquarters at Langton Bay, and travelled eastward, accompanied by the Eskimo Nakutsiaq, until he encountered natives near Cape Bexley. And here a curious thing happened. The people here took him for an Eskimo himself, because he spoke the Eskimo tongue, altogether heedless of his appearance, which of course was that of a white man. When he asked them how it was they could not see at once that he was not an Eskimo they answered that he did not look very much different from some of the Eskimos of Victoria Land where it was very common to find people with grey eyes and fair hair and beard. Stefansson then at once determined to visit a particular spot indicated, and his observations led him to formulate a theory that some of those Norsemen who had been last heard of in Greenland might possibly have made their way to these regions, and intermarried with the Eskimos there.

I admit that we do find, among the Copper Eskimos as well as among those farther east towards King William's Land, a surprisingly large number of types differing in appearance from the ordinary Eskimo; this however, is hardly sufficient to support a hypothesis which claims them as descendants of Norsemen from Greenland. Stefansson suggests that the distance from Greenland to Victoria Land is no hindrance. To this I cannot agree. The ancient Norsemen were great sailors, and did get far to the north with their vessels, but they were hardly well enough up in sledge travelling for such a journey. The last certain record of their movements to the northward is the runic inscription at Upernivik. And without a thorough knowledge of the methods of travelling in the Arctic, the distance between Greenland and Victoria Land becomes a very serious obstacle. Distance is after all a question of transport facilities; and the fate of the Franklin Expedition and the many which followed it afford the best proof of how impossible it would have been for the Norsemen to navigate in these regions. And finally,

Moreover, we have to consider the evidence of tradition. It is hardly imaginable that such an event should have been utterly forgotten among the natives themselves, even after the lapse of a thousand years. There are many stories still current among the Eskimos in Greenland as to the Norsemen and their conflicts with the natives. The blond type is not peculiar to Victoria Land, but is found also in King William's Land and on the Great Fish River; even among the Musk Ox Eskimo I found some with the same reddish or brownish hair and grey or almost blue eyes, and a remarkably strong beard, which last is unusual among the Eskimos generally. And there was no tradition among any of these people as to any foreign blood. I am convinced that these peculiar types are the result of purely biological conditions, which are altogether accidental, and for which no rule can be established.

On the 15th of February we bade farewell to our friends here. There had been excellent sealing for the past month, the finest indeed we had seen, a single day sufficing for the capture of as many seals as would have been taken in a whole month among the Netsilingmiut to the eastward. It was not that the natives here were more than commonly skilful, but the waters here in Dolphin and Union Strait, where the ice is cut about by the currents, seem to be a general meeting place for the seals both from east and west.

With heavy-laden sledges we set out on the 900 km. run to Baillie Island.

We had met at Bernhard Harbor a young trapper named Lyman de Steffany, and afterwards his brother Gus, who lived some distance further west. Both were excellent hunters and drivers, and we were glad of their assistance. Leo Hansen had hurt his shoulder in struggling with the heavy Hudson Bay sledge, and one arm was useless for some time; indeed it was only by a stubborn effort that he was able to go on. The aid afforded us by the two brothers on the journey was thus doubly welcome, and the fortnight we spent travelling in their company was one of pleasant companionship throughout.

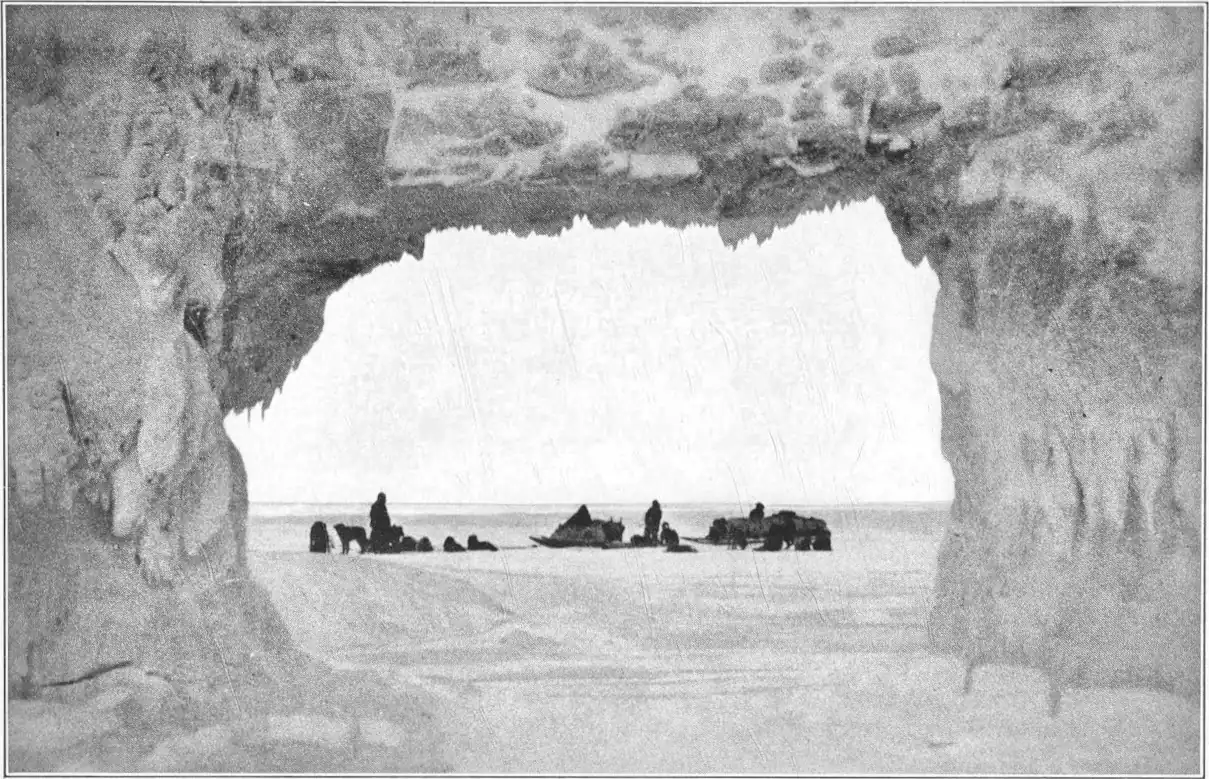

The coast we had now to follow to the northward was for the most part dull and monotonous; it was low-lying country, in many places merging imperceptibly into the tumbled ice and pressure ridges off the shore, and only broken here and there by steep sandstone rocks often hollowed into fantastic caves that afforded a welcome shelter. The ice off shore was good, and when we wanted fresh provisions we had. as a rule only to drive out some ten kilometres where seal could be had without difficulty in the patches of open water. We were loth to waste time on such excursions however, and only turned aside when forced to it. At one place we encountered a solitary Swede, Kalle Lewin, of Kalmar, who quoted Frithiof's Saga with true patriotic enthusiasm, in the intervals of gloomy prophesyings as to the prospects of fox in the coming season. A day's journey farther north, at Pierce Point, in the most beautiful part of the country, amid arches and monuments of ice-embroidered sandstone, we met another trapper named Bezona, said to be an Italian nobleman who had come to the Arctic in search of an Eldorado—up to date without success.

At Cape Lyon we encountered the first Eskimo immigrants from Alaska, who, like the white trappers, were now seeking their fortune in the country of their "wild" tribal kinsmen. They were extremely hospitable, spoke fluent English, and soon proved to be thoroughly businesslike. We did not take long to discover that we were in the land of the Almighty Dollar. A joint of caribou meat such as would have been given us freely as a token of welcome among the tribes farther east, here cost $8, and when we wanted a man and a sledge to help us one day's journey on ahead, as Leo Hansen was still laid up, the price asked for this was $25.

We thought perhaps, for a moment, with regret of the kindly folk we had left, who would have helped us on our way for a week and been only too pleased, without any question of payment. But the principle here was unquestionably right; the Eskimos had now to compete with the white men, and if they were to make ends meet, it was necessary to ask a fair payment for services rendered. We were strangers, merely passing through the country, and had to pay our way.

During the further stages of our journey westward we put on the pace, doing 50 or 60 kilometres per day. This meant that the dogs had to trot, and we ourselves to run beside the sledges, which was perspiring work, but gave one splendid rest at night.

On the 9th of March we halted for a spell at Cape Parry, where lived the trapper, skipper and adventurer Jim Crowford. We got in to his place in the evening, just as the setting sun lit up his little schooner, as she lay icebound, and the corrugated iron hut he had built at the foot of a cliff. It looked chilly enough in itself, but there was smoke rising from the chimney, and it was not long before we were seated at a meal like old friends, listening to our host's account of his adventures in the gold rush of 1900.

On the 15th of March we reached Horton River, where there is an old Eskimo settlement named Idglulualuit; the widow of a well-known German whaler, Captain Fritz Wolki, lives here. We entered a house where everything was so neat and clean and orderly that we instinctively walked on tiptoe, and found three taciturn women who regaled us with roast ptarmigan—dainty and appetizing as could be.

Next day we encountered a natural phenomenon, and camped for a spell to take some pictures, though we could only stay a few hours. We had reached the Smoking Mountains. Long ago, perhaps a hundred years or more, some subterranean deposit of coal here caught fire, and the smoke is still pouring out from ten different hills. In the strong sunlight, they seem wrapped in halos of greyish blue smoke, that oozes out from every crack and crevice in the sides. Here and there among the hollows, white