Across Arctic America/Chapter 22

Chapter XXII

Trade and Prosper

On the 17th of March we reached Baillie Island, where the Hudson's Bay Company has a station, in charge of our fellow-countryman Henrik Henriksen. I need hardly say that he at once invited us to share his comfortable quarters.

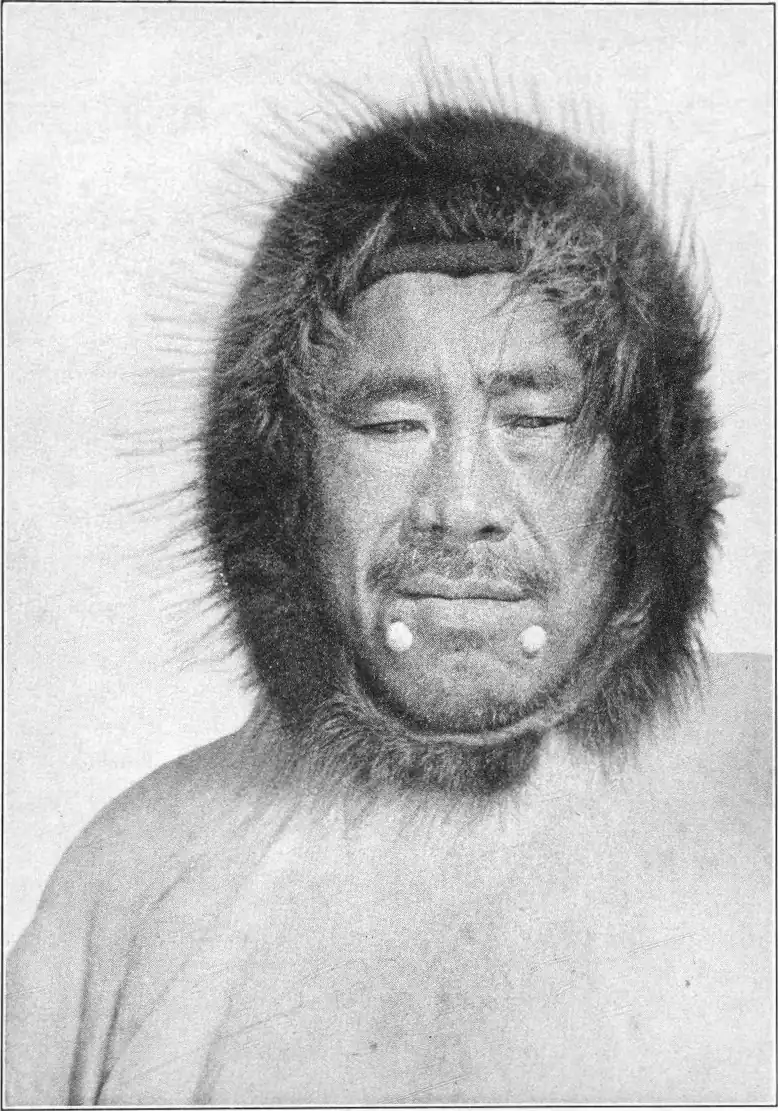

The first part of our journey was thus at an end. I was now among new tribes, the Mackenzie Eskimos.

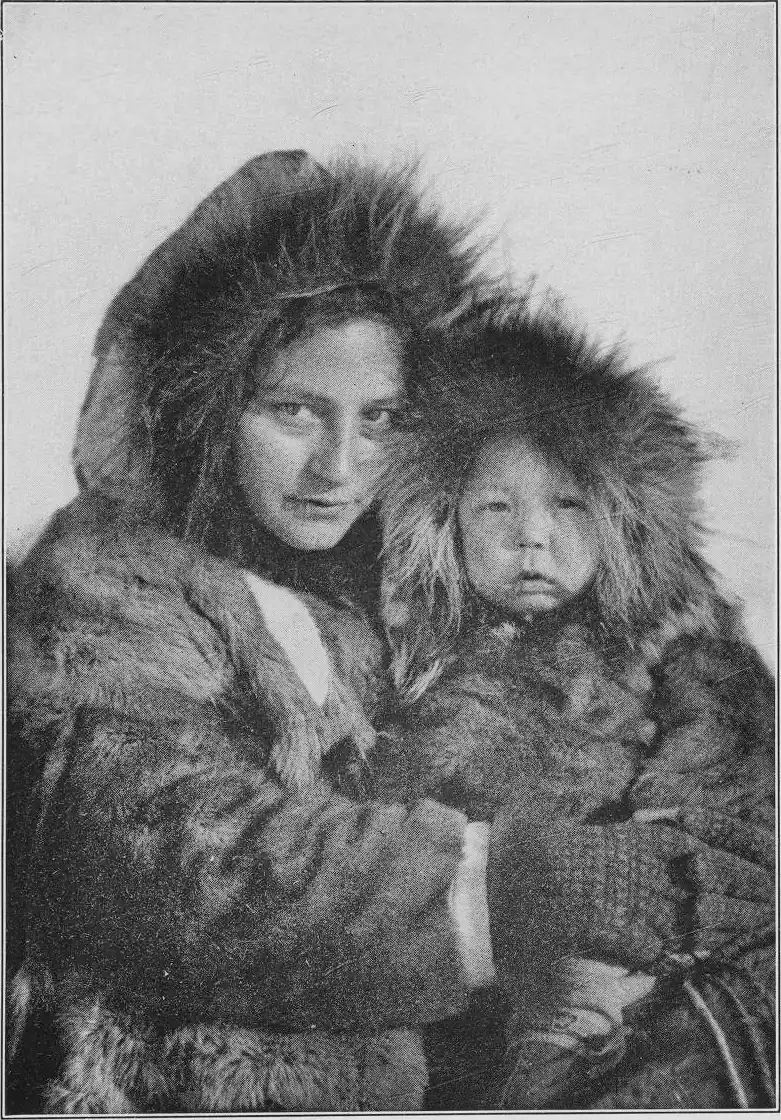

It was like coming into new country altogether. We had been accustomed to living among people who lived chiefly on land game, and only hunted seal from the ice. Here we found ourselves among folk who won their food from the open sea, and spoke a language which was almost exactly like that of the Eskimos in Greenland; they talked of whale and white whale, seal and ribbon seal, which were hunted in kayaks or umiaks. And these umiaks were exactly like those used in Greenland; it was a pleasure to us to see the well-known lines, coming as we did from among people to whom the very name of Greenland was unknown.

The little white snow villages that we had grown so familiar with were here replaced by log huts, or houses built of wood or peat, the arrangement entirely corresponding to that common in Greenland, so that my two Greenlanders opened their eyes and

This was our first impression, but on closer acquaintance we found things very different from what we knew. The Mackenzie River had been the great source of culture, and just as its mighty currents had torn up whole forests by the root and spread the timber far along its shores, so also it had torn up the Eskimo culture from its old surroundings and created a transition form, in the midst of which we found ourselves now. Hunting by sea was no longer the one thing needful. The pursuit of gold and money values had revolutionized everything. The Hudson's Bay Company was no longer the only source and centre of trade; independent traders came down the rivers buying up skins for cash, and the competition between them sent prices up to such a degree that the Eskimos in this rich fur country found themselves wealthy men all of a sudden. And accustomed as they were to reckon from hand to mouth, or at most in terms of a single year's supply of food, their ideas of foresight went no farther than the laying by of a store of meat for the winter; they were all skilful hunters, and it was easy for them to procure, and dispose of, the coveted skins; which they did without any consideration for the future or their old age.

Consequently, we found ourselves now among a people highly paid and independent in proportion. The price of a white fox was $30, and many could be caught between November and April, in addition to the other sorts of fox, and other fur-bearing animals. The Eskimo hunters were no poor savages in kayaks; they owned schooners and called one another "Captain." A schooner of the flat-bottomed type such as is used in the deltas of great rivers could be bought for $3000, but there was not much occasion to use it after all. One could go visiting up and down the coast in summer, or take a sort of fashionable holiday "yachting" after the fur season was over; for hunting proper they used the cheaper and handier umiak, or whaleboats. Most of the schooners of course had motor power, and machinery in general was used as far as possible. The women, whose deft fingers had been wont to compass unaided the making and decorating of clothes, now used sewing machines. Men and women alike had learned to write; and the men, to be in the fashion, bought typewriters, though their correspondence was hardly enough to give them any great practice in the use of them. Safety razors were in general use, and cameras not uncommon. The old blubber lamps, excellent for their purpose, were now sold to tourists as curiosities (price $30), and gasoline or kerosene lamps were used instead.

I felt, indeed, something of an old fossil myself at first, among all these smart business folk; legend and myth and ancient traditions were things they had left far behind. Many a time during those first few weeks did I think wistfully of the eastern tribes, where men and women still had some respect for the wisdom of their forebears. Here, if I wanted folk tales, I found myself confronted with salesmanship; demand created the supply, and a self-styled specialist in folklore, mythology and local information offered his services confidently at $25 per day. He could make that by manual labor; why should he use his brains for less? And as soon as it was noised abroad that we were interested in ethnographical specimens, unblushing "dealers" grew up in a twinkling on every side, asking up to $50 for any trifling ornament.

I felt hopelessly out of my element in all this. But fortunately, all this outward "civilization" was but skin-deep, and it was not long before I managed to arouse the people to some interest in their own past. I talked to them for hours—free of charge—of all that we had seen and learned on our journey hitherto, of their kinsfolk to the eastward who knew their history; and after a while, awoke some response in themselves. Indeed, before leaving western Canada, I had acquired a great amount of new and valuable information myself. But this will be set out in another place. For the present, we must continue our journey.

We held straight on our course towards Herschel Island, halting, however, at any settlements by the way that offered anything of interest. In Liverpool Bay, for instance, I visited a first rate story-teller named Apagkaq. He began by scornful criticism of my interest in such an unremunerative occupation; but when I promised him $50 for five days' work, he grew more interested himself. The work went but slowly to begin with; art and bargaining do not go well together. But after a while the bargain part of it was forgotten, and we worked as brothers. He was unquestionably a magnificent artist, the finest I have met outside East Greenland. He came originally from the region of Noatak River and Kotzebue Sound, and several of his stories bear traces of Indian influence. One of them, "The Wise Raven" is a whole creation myth in itself, and bears notable points of difference as compared with other Eskimo versions. I filled many pages with Apagkaq's stories, and when we parted I could hardly see out of my eyes. I slept on my sledge most of the first two days after. Looking back, I have a faint misty remembrance of meeting a jolly old fellow named Ularpat, the first in these regions to catch white whale in nets. Dried whale meat and blubber was served, the meat was a trifle mildewed, and when this was commented on apologetically, I answered with a Greenland catchword to the effect that mildew was good for the system. Ularpat's retort stuck in my mind. "Yes," he said with a laugh, "we say the same thing in our country; probably to save the trouble of washing the meat clean. Laziness often makes things 'good for you' in that way."

On again to the west. We decide to cut across Liverpool Bay and make for Nuvoraq (Atkinson Point). In the evening we reached the house of a hospitable American, Mr. Williams, where we also met the chaplain, Mr. Hester, with whom we afterwards travelled for some weeks; an earnest and untiring worker, with the welfare of the Eskimos ever at heart. He had formerly been working over in the region of Coronation Gulf, but had been obliged to

On the 5th of April we visited the chief Mangilaluk, whose residence might well be the envy of many a town-dweller dreaming of a country house. It was a log hut built of very heavy timber, the principal apartment measuring 7 metres by 5½, and something over 3 metres high. This, however, was eclipsed by another house of the same type where we spent the night on the eastern bank of the Mackenzie River, where the living room was 7 × 10 metres, and 3½ metres high. The walls here were lined with beaver board, the floor covered with linoleum, and in place of the old-fashioned Eskimo sleeping bench I found a bedroom with two iron bedsteads, spring mattresses and all!

During the past few days, the country has changed altogether; the soil is grassy, and all the valleys thick with water willows.

At Kitikarjuit, formerly inhabited by some 800 Eskimos, and famous for white whale, we found no Eskimos at all, but only the manager of the Hudson's Bay Company's station, and an inspector. The manager, John Gruben, was remarkably well acquainted with the Eskimos of this district.

On the 10th of April we again passed the house of a fellow countryman, Niels Holm, on the eastern bank of the Mackenzie Delta. Here also we found the site of a former Eskimo village, with many ruined houses and graves, especially graves of chiefs, in which the property of the deceased had been interred with the corpse; umiaks, kayaks and sledges.

We were now anxious to get on to a place where we could finish off our work in Canada before entering Alaska. Herschel Island would be the best for this purpose. The delta, however, is difficult country to travel through without a guide, owing to the many tributary streams all looking alike. To avoid losing our way and precious time, we persuaded Niels Holm to accompany us to Herschel Island, where we arrived on the 17th of April.

Herschel Island has an excellent natural harbor, the only real harbor on the whole range between Teller and the Arctic coast; it was first discovered in 1848, and at once became the centre of the whaling industry from Mackenzie River to Baillie Island and even farthest east. The whaling has now altogether ceased, but the harbor remains as a main centre of supply for the east arctic districts, which may at times be completely blocked by ice.

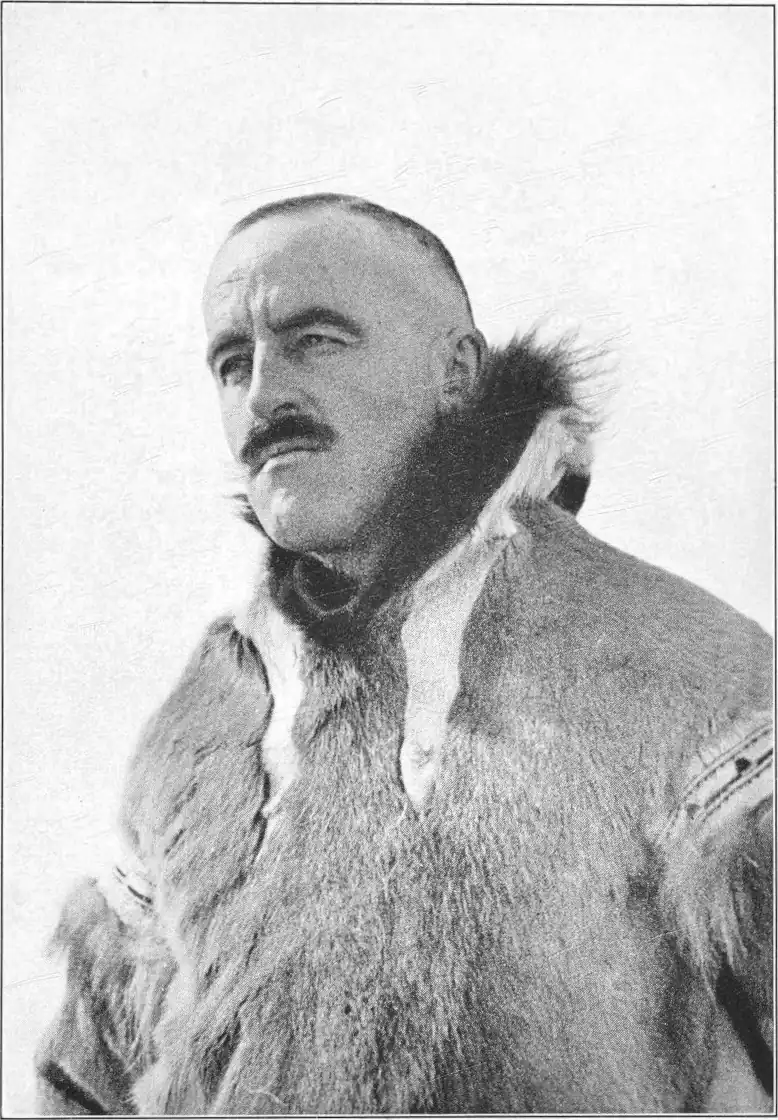

The Hudson's Bay Company has for many years past carried on trade in the Mackenzie Delta. In former times, supplies were only brought down by river. The formation of the many new stations to the eastward, however, necessitated direct communication by sea from Vancouver, and these voyages were accomplished with great skill, often with serious risk. The considerable quantities of goods thus poured in upon a coast where the inhabitants are still in a primitive state has of course its dangers, and it must be admitted that the great trading concern has, despite its mercantile interests, realized its responsibility as the most powerful organization in the district. Throughout the North-west Passage I invariably found the traders on the best of terms with the Eskimos near.

There are wide regions where the Hudson's Bay Company is the only link between the native population and the outer world. The Hudson's Bay Company stands for civilization, and its outposts in these desolate lands represent the life and work of men who bear the white man's burden, the white man's great responsibility.

At the headquarters of the Mounted Police on Herschel Island I had the pleasure of meeting Inspector Wood, who was in charge of the police administration along the whole of the Arctic coast; a keen and capable man, fully alive to the difficulties of maintaining law and order throughout a country extending from Demarcation Point to the Magnetic Pole. To him had fallen the task of hanging the two poor devils from Kent Peninsula the February before, and there were several Eskimo families from the east still at the station, either as witnesses or accused of complicity in cases of homicide. Witnesses and accused alike lived on the best of terms with the police and the local Eskimos, and save for some homesickness, might have been enjoying an innocent holiday, with all expenses paid. The only ones who seemed at all serious about it were the few who might find it their last journey on earth.

The Mackenzie Eskimos were once a great people by native standards; it is estimated that about the middle of the 19th century they numbered about 2000, of which about half lived at Kitigarssuitvarious epidemics, however, have seriously reduced the population since then, and it now amounts to only some 400 souls. Of these again some two hundred are recent immigrants from Alaska, more especially from the region of Noatak and Colville River. In the old days before the Hudson's Bay Company had set up stations in the delta itself, the regular yearly trading trips extended up the Mackenzie River as far as Fort McPherson, or at times even beyond, and though one can now purchase everything needed on the coast, there are still some families that go up to the Arctic Red River, attracted by the rich prospects of trapping in that region, and the fine salmon fishery.

These inland journeys brought them from very early times into contact with the Indians; and here for the first time throughout the expedition I learned that cases of intermarriage between Indians and Eskimos had formerly been common; true, it was marriage by capture, but both Indians and Eskimos agree as to its having taken place. I have often in the foregoing referred to the Indians in the terms used by the Eskimos in describing them; the old stories in particular represent them as cruel, bloodthirsty and treacherous. At Single Point, I met a young Indian woman, the wife of the Hudson's Bay Company's Manager; she had been born and brought up among the Takudh Indians. She

This account, given by an Indian woman, is interesting as showing how the Indians regard the Eskimos; and one cannot say that any great affection exists between them.

Our first meeting with the Western Eskimos thus took place at the close of our three years' exploration in Canada, just before we left the country. We found a people that had changed their ways in most essential respects. Skin boats had given place to schooners, sealing to trapping and fur trading on modern lines; earth-and-stone huts lined with driftwood were now replaced by something approaching modern bungalows or villas; and in addition to all these external changes, their ancient faith had given place to Christianity. One would hardly think that all these changes would be favorable to any continuance of the fellow-feeling between them and their kinsfolk to the eastward; we found, however, that racial traditions lived on unimpaired in their stories and legends. I wrote down over a hundred such, and found a surprising number of old acquaintances among them, both from eastern Canada and from Greenland.

The journey through these sparsely populated wastes was now at an end, and our route henceforward lay through richer and more civilized regions. I was glad, however, to have had the opportunity of studying these people before they had quite given up their ancient ways of life. As it was, I had an abundance of material, and was now more than ever filled with admiration for the Eskimos themselves.

I cannot leave this part of the country without saying that I got a strong impression of the way in which the Canadian Government evidences its feeling of responsibility toward the Eskimos. Admittedly the supervision is difficult, because the people are scattered far along inaccessible shores. Nothing can be done without great expense.

The plan of allotting reservations to the Eskimos is undoubtedly the only right one, for it shields them somewhat in those first meetings with civilization which are always the most dangerous for a primitive people.

Yet in one thing I believe progress is still in order. Now the Government has all of its contacts with the Eskimos through the Mounted Police. With all the admiration I hold for the Mounted, for the way they carry out all usual police duties, and many others, I do not feel that they can justly be expected to substitute for all of the agencies of civilization. Some educational department must be established to deal with the Eskimo on the gentler side. There can be no step back to the Stone Age for any people that has once had contact with the white man. Canada cannot afford to be behindhand in attempting the educational paternalism that has done so much in Greenland and in Alaska to fit the Eskimo to meet the cruder contacts with the white man, in the person of the trader, the competing trapper, and the policeman.