Across Arctic America/Chapter 23

Chapter XXIII

New Ways for the Eskimo

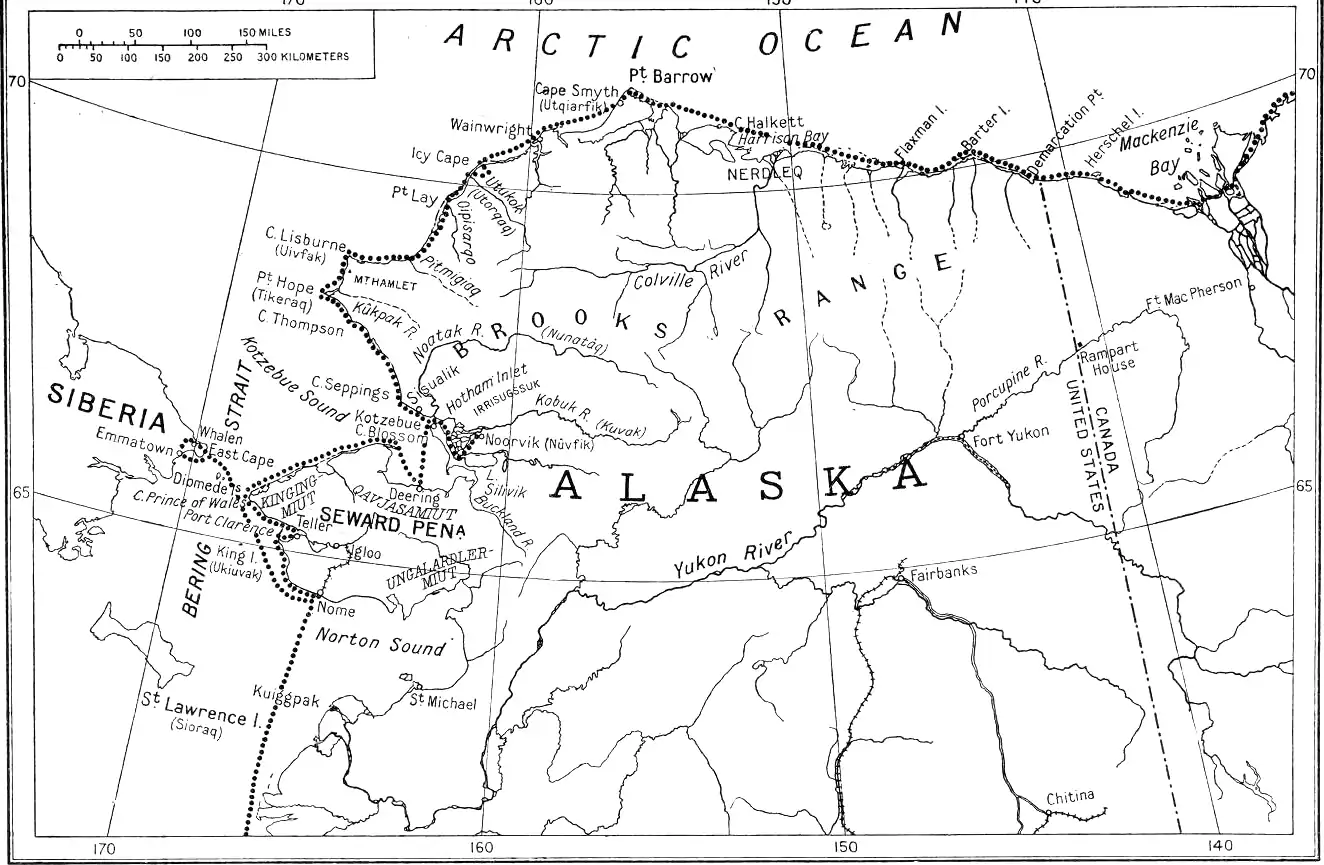

On the 5th of May, early in the morning, we entered Alaska. Near Demarcation Point we passed the line of stakes that marks the frontier; we were in the land of which so many adventurers had dreamed.

We had now a run of 800 kilometres along this barren coast before we could halt for any length of time; the land is now flat tundra, stretching away as far as Point Barrow almost in a straight line, broken only here and there by small indentations of the coastline. Just offshore are narrow sandy reefs, forming the so-called lagoons, where we find fine smooth ice just inside the barrier, very different from the tumbled pressure ridges beyond. The dogs moved at a steady trot, and we ourselves were growing accustomed to trotting alongside.

The Eskimos are scattered about in little encampments all along this coast; we find, too, a few white men, Scandinavians for the most part, some with small schooners, others with nothing but their bare hands and their traps. The distance between dwellings depends on the chances of a good haul.

At last, on the 23rd of May, we found ourselves on the high road, as it might well be called, to Point Barrow, the most northerly settlement in America.

The population consists of some 250 natives and a few white men. There are big shops with stores and warehouses, but what mostly struck us is the presence of a school, a hospital and a church. We had not seen a school for three years, and it looked quite imposing. The schoolmaster in charge was a young Dutchman, Peter van der Sterre, who very hospitably received us as his guests.

I had not expected to find anything of interest on this part of my journey, and really considered my collections at an end on leaving Canada; I soon found, however, that this was not the case. Men and women here were less sophisticated than those of the Mackenzie Delta, and there was a store of folklore and mythology ready to hand. I decided therefore to take advantage of the opportunity, and make some stay here, despite the advice of experts who declared that if I did not push on at once, I should have to wait until August and go on by sea. We were just at the most exciting part of the annual whaling season. Only a few kilometres out from land was the open sea, rocking the loose icefloes; the sea birds had gathered in dense flocks, and their cries could be heard right up over the land. Nearly all the men lived out at the edge of the ice in rough hunting camps; only the women and children were at home. All were excited, and no one ever seemed to go to sleep. When we ourselves went to rest, at four in the morning, and opened the windows, we heard on all sides the chatter of women, the cries of children and the howling of dogs. But on all the highest points of the clay cliffs were watchful outposts, waiting for the moment when they could with a deafening shout, announce to these careless night-birds that a whale had been harpooned.

Alaska was discovered in 1741 by the Danish explorer Vitus Bering, then in the service of Russia and voyaging up through the Strait which bears his name. Little more was known of it however, for many years after. In 1826, an English expedition under Beechy visited Point Barrow and opened the way for others. The Eskimos who lived between Norton Sound and the Arctic Ocean appear to have been a warlike people, their young men being regularly trained for war, hardening themselves by all manner of athletic exercises, dieting themselves, and often obliged to fast in order to habituate themselves to great hardships, or making journeys on foot for many days in succession as a test of endurance. Not only were the different tribes constantly at feud among themselves; they did not hesitate to enter upon combats with Indians or white

This period, moreover, was not so far distant but that I was able to obtain my information from the elders, men and women, whose fathers had themselves taken part in such fights. Russian trading methods proved of little advantage to the natives; indeed, they were well on the way to extermination when the United States, in 1867, bought the whole territory for a sum of $7,200,000; probably the best deal of its kind on record. In 1890, the Bureau of Education set to work to improve the conditions of the native population, and now, after 35 years, we find them industrious, ambitious and independent, a wonderful testimony to the value of systematic educational methods. A point of great importance in material respects was the introduction of tame reindeer from Siberia. Dr. Jackson, the Alaskan Eskimos' greatest benefactor, succeeded in getting some 1280 animals brought over, and there are now close on half a million, with every prospect of running into millions before long.

All the young people of the present day speak English as well as any American, and have thus the first qualification for entering into competition with immigrant whites. That this should be possible is due to the fact that the school was from the first made the centre of everything.

But there was also another form of education which was of importance, and that was the establishment of the so-called co-operative stores. The population contributed themselves towards the funds for starting these, but state assistance was also needed, and the government vessels which inspect the schools and medical service bring up goods for a freight which just covers expenses; the Eskimos thus obtain cheap wares, and can themselves take part in determining the prices of all necessaries. They manage these businesses themselves, under supervision of the two local school-teachers, and it is generally considered that they thus gain experience greatly conducive to the development of their own independence.

During my stay at Point Barrow, I gained a lively impression of the contact between the native population and the white men, who had come into the country to deal with cultural tasks. At the hospital, there was a medical missionary in charge, a Dr. Greist, with his wife, both keenly occupied in social work. Mrs. Greist devoted almost the whole of her time to "The Mothers' and Babies' Club," the principal objects of which were hygiene and care of children. The three nurses at the hospital had also their special tasks, carrying on schools in their leisure time for practical and religious instruction especially for women and children. And through the comfortable school rooms passed a constant stream of men and women, who were invariably received by Peter van der Sterre with tireless and patient helpfulness. I learned, of course later on, that conditions are not equally ideal everywhere; the great difficulty is to get the right kind of workers. But Point Barrow at least was a place where all, from the youngest to the oldest, worked sensibly according to the principles of the Board of Education, and I was glad to obtain the best introduction here at once.

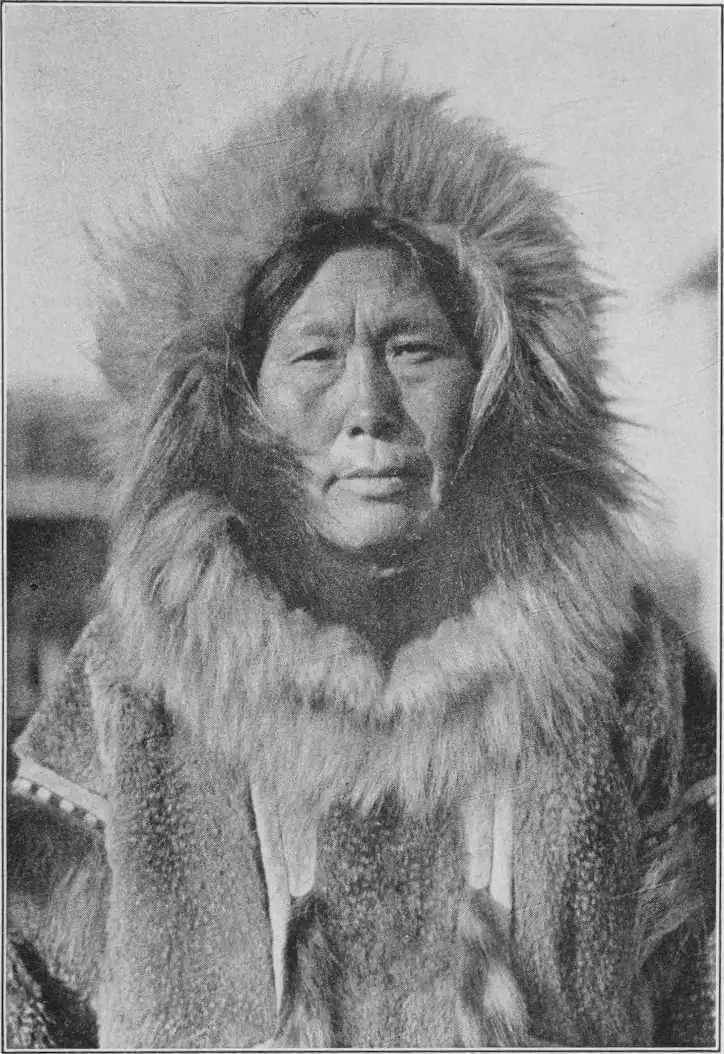

Of great importance to me and my work at Point Barrow was my meeting with a man named Charles Brower, who had lived among the Eskimos for forty years. Mr. Brower was a personality who had with lively interest followed the fate of the Eskimos through all these years, and very thoroughly made himself acquainted with their past history. He had married a native woman from the locality, and spoke the Eskimo tongue excellently. He was rightly called the King of Point Barrow; for there is hardly a man all along the coast who enjoys such respect and veneration both among white men and Eskimos. Mr. Brower and I soon made friends, and thanks to his advice, I was able at once to hit on the spots where there was work to be done, and get into touch with the people who knew what I wanted to learn. My numerous conversations with Mr. Brower are among the most pleasant and most instructive I have ever had.

In Alaska, natural conditions and animal life have necessitated a development of industry on two definite lines: the caribou hunters on the one hand, the whalers on the other. Hunting by sea had its definite seasons, precluding any very nomadic form of life, while the immense areas through which the caribou had to be followed on the other hand made it impossible to keep to the coast in the whaling season. Consequently, some of the natives sailed up the rivers and settled more or less inland, though coming down once a year to the coast for sealskin and blubber, bringing caribou skin and furs in exchange.

Point Barrow has always been one of the main centres for the Eskimo whaling industry. The whales begin to arrive in numbers about the beginning of April, and continue to come in until the first week in June; the whaling was carried on from skin boats out at the edge of the firm winter ice. During the months the whaling lasted, all the men lived uninterruptedly out at the edge of the ice, despite much inconvenience arising from the tabu system. Tents were forbidden, and they had therefore to be content with storm-shelters made of skins, or seek some protection from the elements under the boat. It was also forbidden to dry clothes, and raw food was tabu; all meat had to be boiled. Meantime, the women and children spent an anxious time up in the winter houses. As soon as a whale was captured, they drove out and fetched the meat, which was stored in great subterranean larders, dug so deep down that the meat remained frozen throughout the summer.

The edge of the ice was not so far from land but that it was easy to follow the progress of the hunting from on shore. The skin boats and their crews were posted at spots where the clean straight line of the ice-edge was indented by small creeks cut by the storms. The whales, following the margin of the ice, invariably moved up into these creeks, where

The tradition of many generations, and years of practice, had given steersmen and harpooners great skill in calculating the movements of the whale. All the boats lay on the ice ready to be tipped off at a moment's notice, and the whale, as a rule, passed so close that it could be harpooned from the ice itself. At the same moment, all the boats put out, scattering over several kilometres round, and waiting for the whale to come up again, when it would be given a few more harpoons, with lines and bladder floats, to drag along; these checked its pace, and enabled the hunters to come to close quarters with their great lances, which were thrust in at a spot where the flint head could be sure of penetrating. The next thrust would be directed towards one of the great arteries in the neck; or an attempt would be made to sever the tail fin; the whale could then no longer dive, and was easily killed.

Only occasionally was a whale attacked in open sea; this being a far more difficult matter. When it was done, the hunters could, however, reckon with the fact that a whale approached from the front sees badly but hears fairly well, while if approached from behind, it cannot see, and hears but poorly. Anything coming from either side, however, it can both see and hear a considerable distance off. The first time a whale was harpooned it would come up some 3–4 kilometres from the spot where it went down; but as the boats always lay spread out along the edge of the ice, it would not be long before the lances got to work and the whale was despatched.

With these primitive implements of the stone age type, the hunters could, in a single spring season, account for up to 22 whales at Point Barrow alone. Considering what this means in meat and blubber and hide, it is not hard to understand that in this district in particular there was the possibility of a flourishing period of culture.

An Eskimo who is a practised whaler is called "Umialik," a word which, originally meaning merely the owner of a boat, has come to have the significance of "chieftain," as the great boat-owners, the more daring whalers, had unrestricted authority over their crews, and held the position of chieftains in their own communities.

Whaling implements were only allowed to be used for one season; this applies to the skins of the boats, and all gear and equipment. In earlier times, all the harpoons were burned with the other implements in a great bonfire during the festivals held at the conclusion of the season; later, it became the custom simply to hang up the harpoon heads on a frame, where they were left until the chieftain died, when they were placed with him in his grave.

When a man had got his first whale, it was his duty, at the great whaling festival, to throw away all that he owned of furs and other things; his fellow-villagers had then to fight for a share, the costly furs being cut into fragments that as many as possible might have a part. Altogether, there were many remarkable and amusing customs associated with the whaling. As a rule the greatest weight was attached to meaningless magic songs that had to be declaimed immediately before harpooning was to take place; there were, however, also other important points to be observed before setting out, customs originating in the belief that the whale, in the earliest days of the world, had been a human being, just as had other animals.

The whale is dangerous to hunt, but is also amenable to advances from human beings, especially women. Thus, for instance, a chief's wife, on learning that her husband's crew has harpooned a whale must at once take off one boot and remain quietly in her house. This preliminary step towards undressing was supposed to affect the soul of the whale and draw it towards the house. When then the boat neared the land, she must fill her water-vessel with fresh water and go down to the dead whale in order to refresh its thirsting soul with cool water.

The chieftain himself mostly took the part of steersman; it is reckoned a great art to calculate the movements of the whale. He would choose for his harpooner a young and powerful man, whose duty was to drive the harpoon into the whale as soon as he gave the signal. On the day before going down to the ice edge to begin the whaling, the young harpooner had to sleep in the forepart of the boat, and would be visited there in the course of the night by the chief's wife. A chief had as a rule several wives, and it was the harpooner's right to be visited by the youngest and prettiest. This meeting with a woman put the young man into high spirits, and the soul of the whale also was supposed to be attracted by the idea of being killed by a man coming straight from a woman.

That is the way whaling was carried on in the olden days. Now, the old harpoons with their ingeniously worked flint and slate heads are long since relegated to the category of antiques, and instead, a modern "darting gun," with explosive bombs, is used. Only the skin boat still remains; it is considered the most practical form of craft, as it has often to be carried long distances over the ice.

I had learned that there was a considerable encampment of inland folk on the Utorqaq river, and decided to go up, with Miteq and Anarulunguaq, and visit them, Leo Hansen remaining behind to get some pictures of the festival which the natives celebrate on the conclusion of the whaling season. He would then come on by sea when navigation opened, and bring our collections through to Nome.

On the 8th of June we reached the mouth of the Utorqaq at Icy Cape, or as the Eskimos call it Qajaerserfik, "the place where kayaks are lost." The name is probably due to the fact that the settlement is built on a sandbank so low that it is sometimes flooded when the wind blows hard on shore. It was spring, but the blizzards were by no means over; the trading station at Wainwright was so com

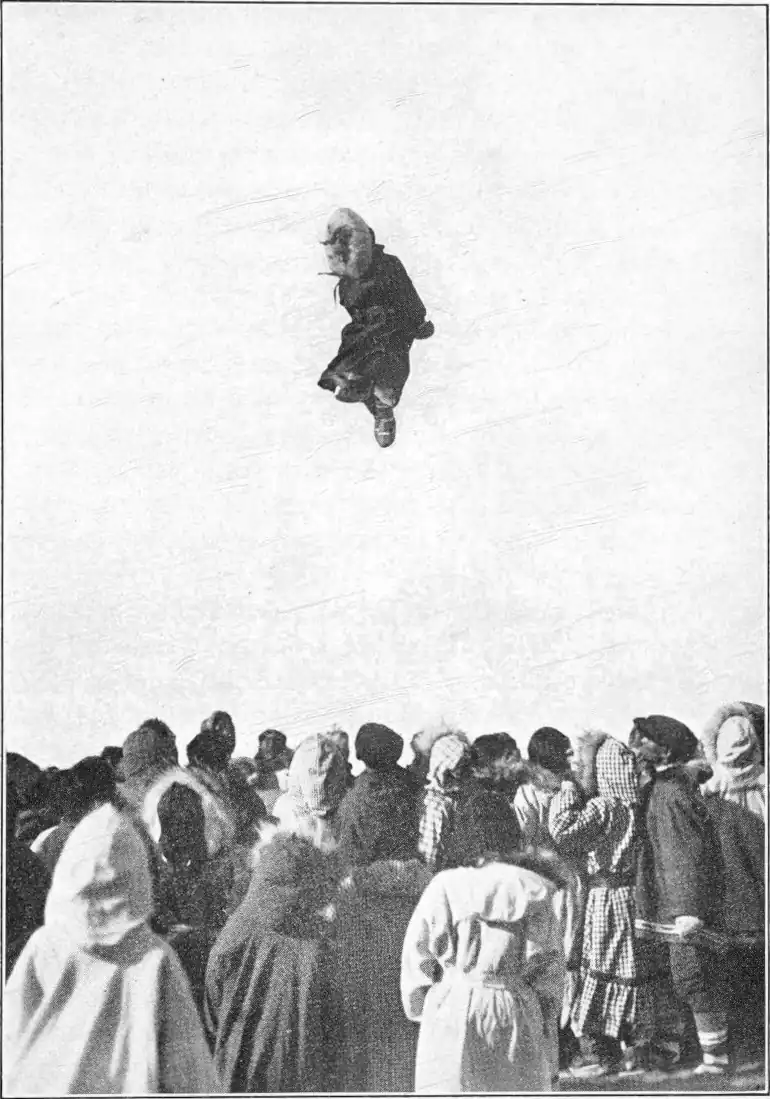

Certain parts of the whale meat—the tail, dorsal fin and the skin from the jaws—are set aside as delicacies for the feast. There are games, including a glorified form of tossing in a blanket, two walrus hides sewn together being held out by as many hands as can find a hold, and the victim then shot up into the air, endeavoring to come down upright and feet foremost. Roars of laughter greet those who fail; and not infrequently broken bones may result. When this has gone on for some hours, the feasting begins, and lasts for the rest of that day and the night, with intervals of singing and dancing. Ten performers with drums sit in a row, with a chorus of male and female voices gathered round; the dancers, generally two women and one man, came in by turns. I was rather disappointed in the songs, which were little more than refrains as an accompaniment to the dance, with no text to speak of; certainly nothing to compare with the lyrics I had found among the North-west Passage Eskimos.

On the following morning we set off for the mainland, to the village where I proposed to stay for the present. Besides the old men and women I had specially wished to see, there were some young reindeer herdsmen, rounding up a herd of some 800 head. The season's calves had to be branded, which is done by marking the ears with the owner's particular sign.