Across Arctic America/Chapter 24

Chapter XXIV

The Gift of Song and Dance

The north and north-west corner of Alaska, comprising all that vast plain to the north of the Endicott Mountains, is watered by great rivers, which have played a great part as channels of communication during the period before the arrival of the white men. Three rivers rising close together gave rise to the many villages in the interior, and served as waterways through the country, in which all the Eskimos formed one community, with winter quarters close together. The three rivers are the Noatak, flowing into Kotzebue Sound, the Utorqaq, debouching into great lagoons between Icy Cape and Point Lay, and finally, Colville River, with its great delta meeting the Arctic Ocean near Cape Halkett.

The Eskimos call the Colville River Kugpik, or the Great River, but the dwellers on its banks are called Kangianermiut, after one of its tributary streams. It is quite near the source of the Utorqaq, only separated by a range of hills, the Qimeq, the distance between them being so slight that skin boats can easily be carried from one river to the other.

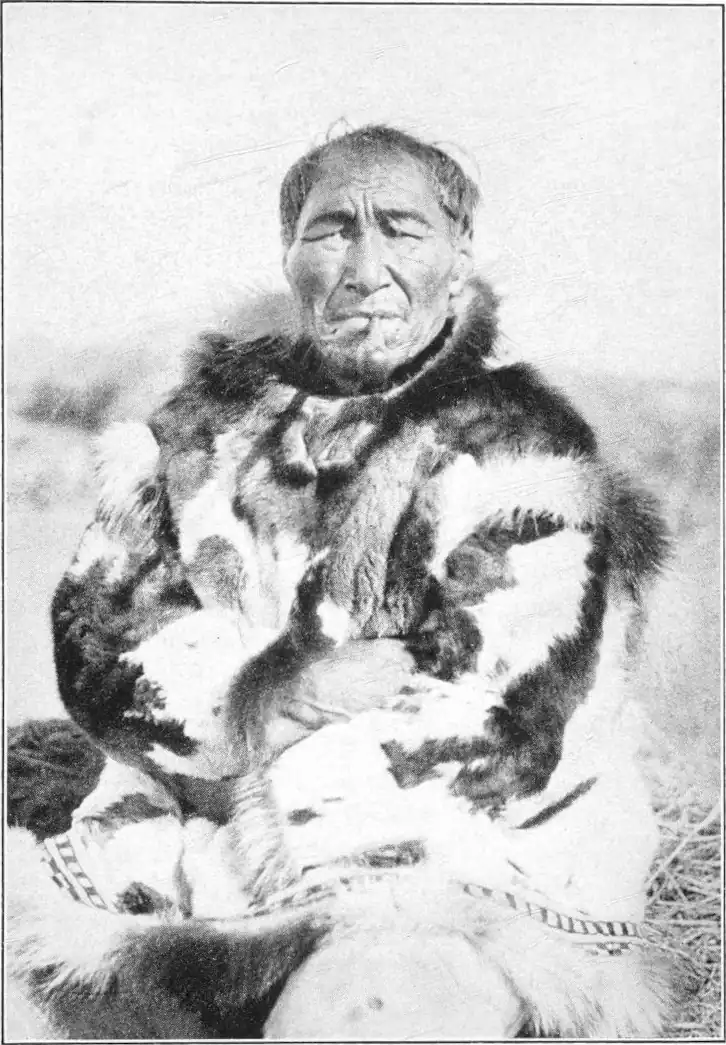

The Kangianermiut sailed down the Colville River in the spring, when the channel was clear of ice; often fifty boats at a time, or something like 500 souls. Little wonder that the Indians feared them! The journey up river took longer, and the boats had to be towed by men and dogs together over the many reaches where the current was too strong for paddling. A great camp was formed in the delta, and in the course of the summer, salmon were caught in great numbers for winter use, the implements used being nets made of caribou sinew. Caribou hunting was also carried on at the same time for present needs. The object of the visit, however, was to procure blubber from the natives round Point Barrow, who came out here to trade. Encounters with the Indians were not infrequent, and every man who had slain an Indian was tattooed at the corners of the mouth as a mark of distinction.

All these people loved their inland life and the merry journeys up and down the river in parties. In summer they lived in tents of caribou skin, built to a special pattern, on a wooden framework of some twenty branches interwoven so as to form a kind of beehive dwelling, easy to heat. A tent of this kind is called Qalorvik. Winter houses were built on the same principle, but with a stronger framework, and covered, first with peat or moss, and then with earth stamped down to form a hard crust. The inside was then lined with a thick layer of branches to prevent the earth from crumbling down. The whole was then built over with snow blocks, resembling an ordinary snow hut; indeed, it was probably modelled on this. Large stones set in the middle of the floor formed a fireplace, and a hole was left in the roof above to let out the smoke.

Thus, roughly, was the round of life among the dwellers on the great rivers. Generally speaking, they lived at peace among themselves, and also with the coast folk with whom they traded. But with those living farther off, they were constantly at war, and constant watchfulness was necessary, as their enemies might at any time swoop down upon any party that could be taken unawares. The men always lay down with their weapons ready to hand.

After the primitive methods in use among the Caribou Eskimos of the Barren Grounds, it was interesting to see the degree of skill and ingenuity which these people had developed in their methods of hunting, apart from the spiritual culture. I noted no fewer than twenty such methods of capturing or killing various kinds of game, and took down, from the lips of my informant, Sagdluaq, details of the most important.

As regards their religious ideas, I found here, despite the difference in conditions of life as compared with the eastern tribes, the same fundamental principles as I have already noted. Their spiritual culture, like their material, was on a higher level, but based on the same ideas of tabu, of spells and charms and propitiation of evil spirits, with the angakoq as mediators between them and the supernatural powers. It has hitherto been generally believed that incipient totemism existed in these regions, and the marks found on implements have been adduced as evidence of this. Were this the case, it would mean a breach of continuity between the eastern and the western tribes. I therefore devoted particular attention to the study of this question, and came to the conclusion that the marks found on harpoons, knives, and implements generally, which had formerly been regarded as totem marks, were purely personal, a means whereby the owner could readily identify his property, as we might use initials or a crest.

Here also we find the dominant principle of rites and prohibitions in connection with the different animals hunted; skins of caribou must not be worked on near the sea, nor those of the seal within sight of the river; certain work must only be done at certain seasons, and the like. Particular rules obtained in regard to caribou caught in traps; such animals must never be cut up with iron knives, but only with flint or slate; and the meat had to be cooked in special pots.

Wolf and wolverine are more or less of a luxury, inasmuch as their flesh is not eaten, and they are only sought for as providing a finer sort of fur for trimmings. The hunter who aspires to the pursuit of these must not cut his hair, or drink hot soup, for a whole winter, and no hammer of any sort must be used in his house. On returning home with the skin of a wolf, intricate ceremonies have to be observed, in which the neighbors also take part.

The hunter must first walk round his own house, following the sun. For a male wolf, he strikes his heel four times against the wall of the house, five times for a female, indicating the four and five days' tabu for male and female respectively. At the same time, the women inside the house must bow their heads and turn their faces away from the entrance, while a man runs out and informs all the men in the other houses of the kill. Then all go out with their knives, in the hope that the soul of the wolf, supposed to be still present in the skin, might "like" their knives and let itself be caught by them next time. The hunter then carries the skin to the drying frame and hangs it up; a young man runs up with a piece of caribou skin which he hands to the hunter. The latter then strips, and standing naked in the snow, rubs himself all over with a piece of caribou skin, after which a fire is lit, and he further cleanses his body by standing in the smoke. His knives, bows and arrows are hung up beside the wolf's skin and all present cry aloud: "Now it sleeps with us"—"it" being the soul of the wolf.

The hunter then enters his own hut and sits down beside his wife, all the women still sitting with heads bowed and faces averted. The hut is then decorated with all the most valuable possessions: knives and axes, often of flint or jade, are hung up, bead ornaments, tools, anything a wolf might be supposed to like, or that the family specially value. Then all the men of the village come in, and the hunter tells stories, not to amuse his guests, but to entertain the soul of the wolf. It is strictly forbidden to laugh or even smile; the wolf might then become suspicious and take it for gritting of teeth. Two stories must always be told, as one "cannot stand alone." Then the visitors leave, and all can retire to rest.

But the ceremonial is not yet done with. On the following morning, the soul of the wolf has to be sent on its way. The hunter falls on one knee by the fire place, with a white stone hammer in his hand, and sings a magic song, and then howls: "Uhu!" four times for a male, five times for a female wolf, and raps four or five times on the floor of the hut. He then runs out and clambers up on to the roof, listening at the window, while another man takes his post by the fireplace and cries out, "How many?" The hunter outside answers "Four" or "Five" according to the sex of the wolf, and the man within howls accordingly. This ceremony has to be repeated in all the other houses. Then all the men walk up to the place where the skin is hung up, and the same formality is gone through once more, all crying at last:

"Leave us now as a good soul, as a strong soul!"

And now, but not before, a great banquet is held

No hunter may kill more than five wolves and five foxes in one season; as soon as this number is reached, all his traps have to be taken in. Neglect of this precaution involves either loss of the animals already caught, or the risk of being bitten to death.

This cult of the beast-soul, or the continuation of life after death, reappears in numerous myths designed to instruct the inexperienced. A point repeatedly emphasized is the slight difference between human and animal life, and we find constant reference to the times when beasts could turn into men and men often lived as beasts. I give one of these myths as told me by Sagdluaq, of Colville River.

How Song and Dance and the Holy Gift of Festival First Came to Mankind

"There were once a man and a woman who lived near the sea. The man was a great hunter, sometimes hunting game far inland, and sometimes seal in his kayak.

"Then a son was born to these two lonely ones, and when the boy grew up, his father made for him a little bow for shooting birds, and in time he grew to be very skilful with this. Then his father taught him to hunt caribou, and the son grew to be as great a hunter as his father. And so they divided the hunting between them, the son hunting caribou in the hills while his father went out to sea hunting seal in his kayak.

"But one day the son did not come back from his hunting. In vain they waited for his return; in vain they searched for him after; no trace could be found. Their son had strangely disappeared.

"Then they had another son. And he grew up, and became strong and skilful like his brother, but he too disappeared one day in the same mysterious manner.

"The man and the woman then lived alone, knowing nothing of any others, and mourning greatly the loss of their two sons. Then a third son was born to them; and he grew up like his brothers, fond of all manly sports, and even from childhood eager to go out hunting. He was given his brothers' weapons, first the little bird bow, then the great strong bows for reindeer, and it was not long before he grew as skilful as his father. And between them they brought home much meat, the father from the sea, and the son from the land, and had to build many store frames for all the game they killed.

"One day the son was hunting inland as was his wont, when he caught sight of a mighty eagle, a great young eagle circling in the air above him. He soon drew forth his arrows, but the eagle came down and settled on the ground close to him, thrust back its hood and appeared as a human being. And the eagle spoke to the hunter and said:

"'It is I who killed your two brothers. And I will kill you too unless you promise me that song festivals shall be held on your return. Will you or will you not?'"

"'I will do as you say, but I do not understand it. What is song? and what is festival?'

"'Will you or will you not?'

"'I am willing enough, but I do not understand.'

"'Then come with me, and my mother shall teach you. Your two brothers would not learn, they despised the gifts of song and festival, and therefore I killed them. Now you shall go with me, and as soon as you have learned to join words together in a song, and learned to sing it, and learned to dance for joy, then you shall be free to return to your home.'

"So they went up over the high mountains. The eagle was now no longer a bird, but a young and powerful man in a wonderful dress of eagle skin. Far and far they went, through many valleys and passes far into the mountains, till they came to a house high up on the top of a mighty cliff, from where they could see out over the plain where men were wont to hunt the caribou. And as they neared the house there was a strange beating sound, like mighty hammers, that rang in the hunter's ears.

"'Can you hear anything?' asked the eagle.

"'Yes, a deafening sound as of hammering.'

"'That is my mother's heart you hear beating!'

"Then they came to the house, and the eagle said:

"'Wait here; I must tell my mother you are coming.' And he went in.

"In a moment he came out again and took the hunter into the house with him. It was built like an ordinary human dwelling, and within sat the eagle's mother, aged, weak and sad. But her son spoke aloud and said:

"'This young man has promised to hold a song festival when he comes home; but he does not know how to put words together and make songs, nor how to sing a song, nor how to beat a drum and dance for joy. O Mother, human beings have no festivals, and here is this young man come to learn!'

"At these words the eagle's old mother was glad and wakened more to life. And she thanked him and said: 'But first you must build a big house where all the people can gather together.'

"So the two young men built a Qagsse bigger and finer than any ordinary house. And then the old eagle mother taught them to make drums, and to set words together making songs, and then to beat time and sing together, and last of all to dance. And when the young hunter had learned all that was needful, the eagle took him back to the place where they had first met, and from there he went back alone to his own place. And coming home, he told his father and mother all that had passed, and how he had promised the eagles that festivals should be held among men.

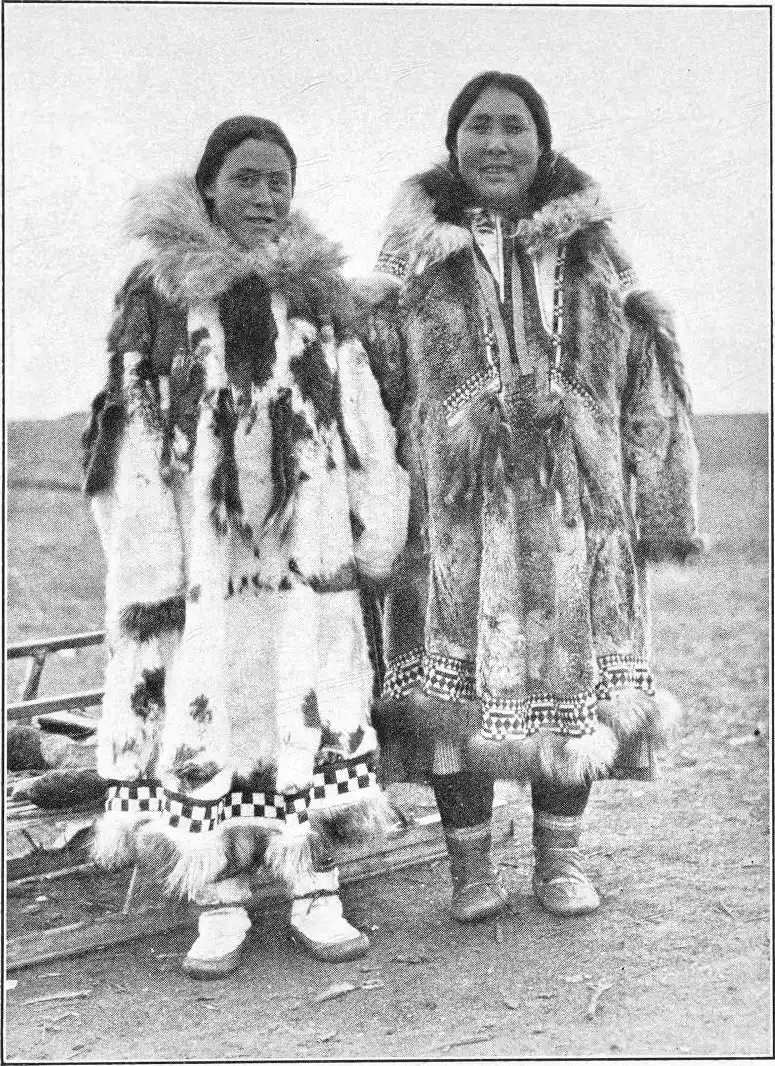

"Then father and son together built a great qagsse for the festival, and gathered great stores of meat, and made drums and made songs ready for the feast; and when all was ready, the young man went out over great far ways seeking for others to join in the feast, for they lived alone and knew of no others near. And the young man met others coming two and two, some in dresses made of wolfskin, others in fox skins, or skins of wolverine; all in different dresses. And he asked them all to the festival.

"And then the feasting began, first with great dishes of meat, and when all had eaten, gifts were given them of other things. Then came the singing and dancing, and the guests learned all the songs and could soon take part in the singing themselves. So they sang and danced all night, and the old man beat the drum, that sounded like great hammers; like the heart of the old eagle mother beating. But when it was over, and the guests went away, it was seen that those guests in the skins of different beasts were beasts themselves, in human form. For the old eagle had sent them; and so great is the power of festival that even animals can turn into human beings.

"And some time after this, the young man was out hunting, and again met the young eagle, who took him as before to the house where his mother lived. And lo, the old and weakly mother eagle was grown young again; for when men hold festival, all the old eagles regain their youth; and therefore the eagle is the sacred bird of song and dance and festival."