Across Arctic America/Chapter 25

Chapter XXV

Uncle Sam's Nephews

I had now to bid farewell to some of my faithful dogs. It was impossible to take them all the way back with me, and I was anxious to leave them somewhere where they would be well cared for. I therefore handed over the majority to Ugpersaun, the trader at Icy Cape, keeping only four in case we might have need of them later on.

I had been warned that it would be impossible to travel along the coast of Alaska at this season, and was prepared for the worst. Sledging was dangerous, as the ice was already adrift in many places; we therefore decided to sail through the lagoons. Part of the way we were towed by the dogs, where the coastline admitted of this; the animals trotted along on shore, with the boat at the end of a long towline out in the water; often at such a pace as to send up a fountain of spray from the bows. At times we ran aground in the shallows, and had to turn out and wade about looking for some passable channel. After three days of this we reached Point Lay, where there was an Eskimo village.

The natives here were too well off for words. My host, Torina, had a store of coffee, tea, sugar, flour, tobacco, petroleum almost enough for a year, with a

On reaching the Pitmigiaq River we found some Eskimos with a rotten old skin boat who undertook to get us through to Point Hope. That boat was a marvel. The skins were so rotten that they were past patching; we stuffed the holes with scraps of reindeer skins and woollen comforters that trailed their ends in the water after us. And in this crazy coffin ship we rounded the dreaded Cape Lisburne.

On the 16th of July we entered the great lagoon at Point Hope, and here encountered the local missionary, Mr. Wm. A. Thomas, out in his motor boat with his wife and son. They took us in tow, and a few hours later we were in their comfortable home, hospitably invited to stay as long as we pleased.

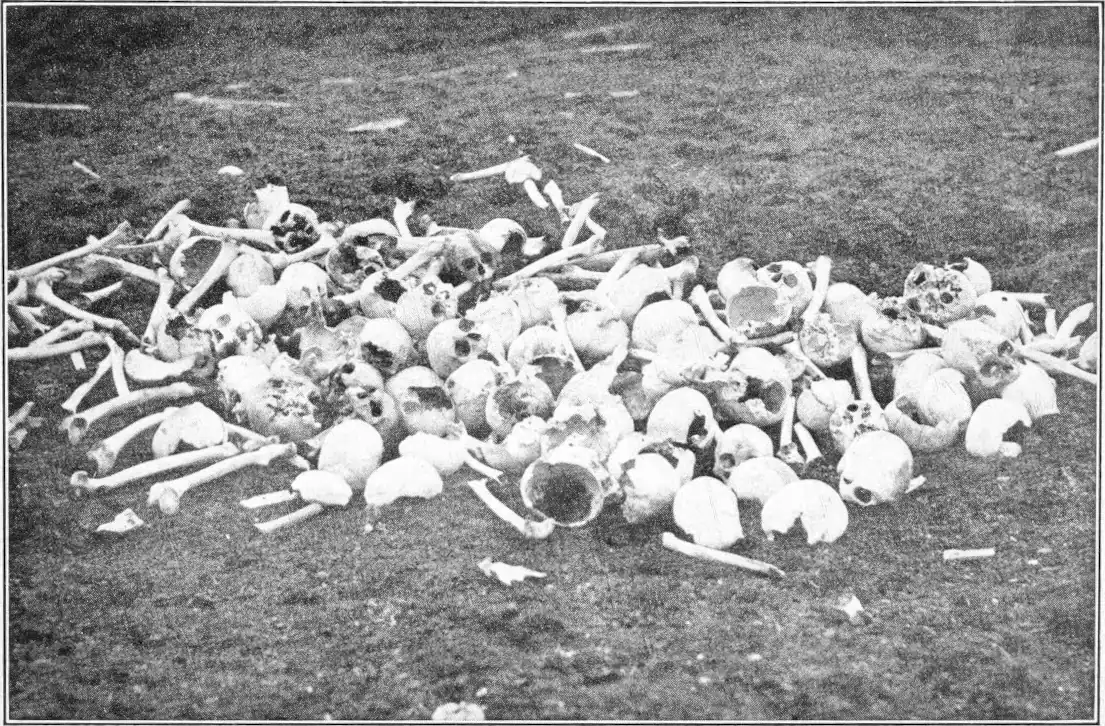

Point Hope, or Tikeraq, "the pointing finger," is one of the most interesting Eskimo settlements on the whole coast of Alaska, and has doubtless the largest collection of ruins. The old village, now deserted, consists of 122 very large houses, but as the sea is constantly washing away parts of the land and carrying off more houses, it is impossible to say what may have been the original number. Probably, the village here and its immediate neighborhood had at one time something like 2000 souls, or as many as are now to be found throughout the whole of the North-west Passage between the Magnetic Pole and Herschel Island. Human bones are scattered about everywhere, and Mr. Thomas informed me that he had himself during his short term of residence seen to the interment of 4000 skulls!

The whaling here is still excellent, and there was abundance of everything, with no fear for the coming winter. I arranged with a couple of storytellers to work with me, and thanks to the kindness of my host, Mr. Thomas, was able to spend my time to the best advantage. Qalajaoq, a notable authority on local affairs, gave me the following account of the origin of the place:

"In long forgotten times, there were no lowlands here at the foot of the mountains, and men lived on the summit of the great mount Irrisugssuk, south east of Kotzebue Sound; that was the only land which rose from the sea; and on its top may still be found the skeletons of whales, from those first men's hunting. And that was in the time when men still walked on their hands, head downwards; so long ago it was.

"But then one day the Raven—he who created heaven and earth—rowed out to sea in his kayak far out to sea, and there he saw something dark moving and squelching on the surface of the water. He rowed out and harpooned it; blood flowed from the wound he had made. The raven thought it must be a whale, but then saw that it was a huge dead mass without beginning or end. Slowly the life ebbed from it, and he fastened his towline to it and towed it in to the foot of the hills south of Uivfaq. Here he made it fast, and on the following day, when he went down to look at it, he saw it was stiff; it had turned into land. And there among the old ruins of houses may still be seen a strange hole in the ground; that is the spot where the raven harpooned Tikitaq. And that is how this land came."

The Tikerarmiut were once a mighty people, and there is a legend of a great battle fought by them on land and sea against the Nunatarmiut, somewhere near Cape Seppings; the Tikerarmiut were badly defeated, and never regained their former power. Then in 1887 came the establishment of the whaling station at Point Hope. The chief of that period, Arangaussaq, endeavored to oppose the progress of the white men, but without avail, and on his death the natives made peace with the whites, who thence forward assumed the mastery.

Point Hope is most interesting as a centre and repository of the ancient Eskimo culture, with much that is not found elsewhere. I gained some considerable knowledge of their more particular mysteries from Qalajaoq. A notable feature is the use of masks and figures in their festivals, which is carried to an extraordinary degree.

The angakoq, after a visit to the spirit world, endeavors to give a record of what he has seen by carving masks to represent the different faces he has seen, the spirits also being present. He further calls in the aid of others, who carve according to his instructions, producing a great number of remarkably fantastic masks. Special songs and dances are composed, and used in conjunction with the masks at the great feasts, which are held at different seasons in honor of the different animals forming the staple of food.

Greatest of all is the Great Thanksgiving Festival to the souls of dead whales. This is held in the qagsse, which serves ordinarily as a place of assembly for all the men of the place, but on special occasions as a temple or banqueting hall. The upper part of the interior at the back is painted to represent a starlit sky, much trouble being taken to procure colored stones to serve for pigments. A carved wooden image of a bird hangs from the roof, its wings being made to move and beat four drums placed round it. On the floor is a spinning top stuck about with feathers; close by is a doll, or rather the upper half of one, and on a frame some distance from the floor is a model skin boat, complete with crew and requisites for whaling.

The proceedings open with the singing of a hymn; then a man springs forward and commences to dance; this, however, is merely the signal for mechanical marvels to begin. The bird flaps its wings and beats its drums with a steady rhythmic beat. The top is set spinning, throwing out the feathers in all directions as it goes; the crew of the boat get to work with their paddles; the doll without legs nods and bows in all directions; and most wonderful of

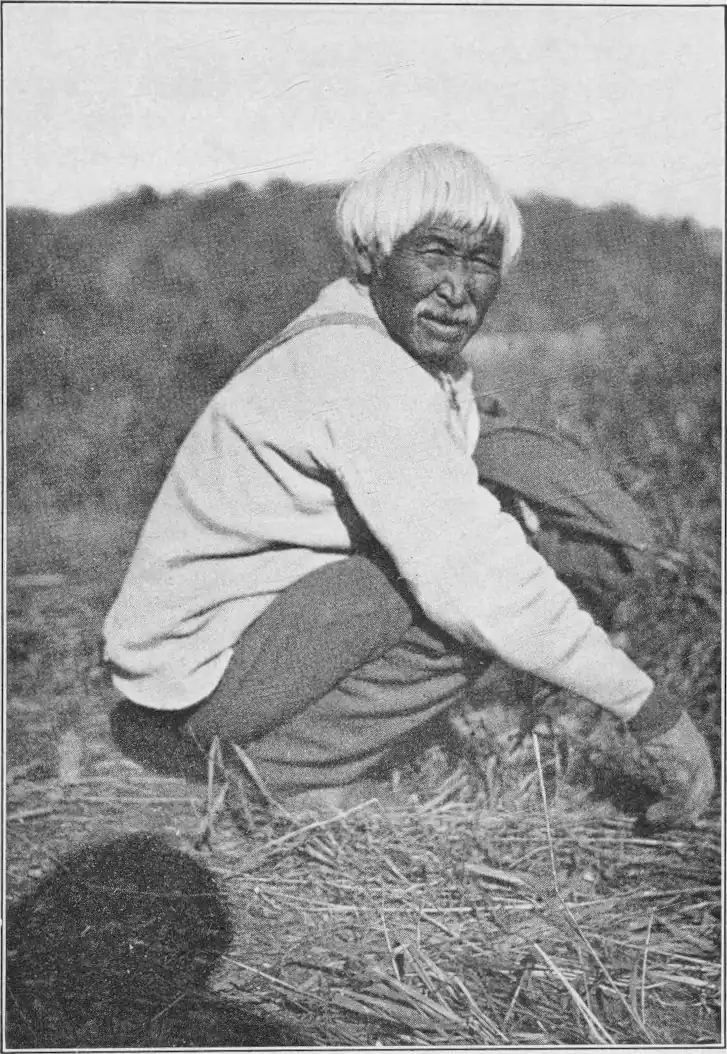

On the 31st of July, having collected a great store of folklore, and finding the weather more favorable, I decided to push on. We travelled now in a little dinghy with motor attached, keeping close in to shore and visiting natives here and there. We met Elektuna, the first of the Eskimos to own tame reindeer; he has now a herd of 800 head, tended by himself and two sons. On the 3rd of August we came to a camp of young people from Noataq River, with a herd of 3000 reindeer, of which 1000 were the property of a single man. These people were cleanly, intelligent, well to do, and contented, retaining many of their sound Eskimo qualities, but speaking English fluently, and living as traders, in direct communication with Seattle.

At last, on the 7th of August, we crossed Kotzebue Sound; the water was shallow, and perfectly fresh, as three rivers, the Noatak, Kuvak and Silivik, flow out into the sea just here. We had to make a wide sweep round, following different channels, and landed late in the evening among gold-diggers, traders and Eskimo salmon fishers.

Kotzebue was an outstanding point on our long journey; for here it was that I could get into touch once more with the outer world, after three years of exile; here at last I should find a telegraph station—the most northerly in America. Naturally then, my first errand on landing was to send a message home announcing the successful completion of our long sledge trip. We had pitched our camp among the Eskimo tents, and the telegraph station lay in the opposite end of the town. And my mind was very busy as I strode down to the office, mentally writing out my message on the way.

I was not a little disappointed then to learn that the telegraph, newly installed, was not in working order at the moment; the operator, whom I had looked to electrify with my news, listened stolidly, and suggested at last that I might try to get through from The Boxer, a vessel lying some ten miles to the south. This meant waiting till next day with a sleepless night between, and this too failed. I had perforce to return to the office in Kotzebue again, and it was two days—the longest on the whole expedition—before the operator succeeded in getting through to Nome. The same evening I had the reply from Copenhagen. All was well at home, and my comrades had got through successfully.

The good news affected me to such an extent that for the first time in months I put aside all thought of work, and treated myself to an unlimited rest. I slept for twenty-four hours, to the great astonishment of those about me. Thus refreshed, I could look about for the best means of utilizing our stay here until the mailboat from Nome could take us on.

Kotzebue (Qeqertarsuk) was the biggest town we had visited as yet, with a school, postoffice, the aforementioned telegraph station, and five or six big shops. Then there were gold diggers of various nationalities; and a camp of about a thousand Eskimos.

In the white traders' quarter, I came upon an enterprising young native, Peter Sheldon, who owned a small motor boat, a neat and swift little craft with cabin and skylights; the very thing for a trip up the river and a glance at the country round. I arranged with him to go up the Kuvak as far as Noorvik, of which I had heard a great deal already.

Noorvik is a remarkable place, a township built to order, for the Bureau of Education. It had been found difficult to work with the numerous scattered little Eskimo villages with a few children in each, and arrangements were therefore made to shift them up inland where they could be taught together, and at the same time removed from the danger of demoralizing influences on the coast. The result was a model town of 300 inhabitants.

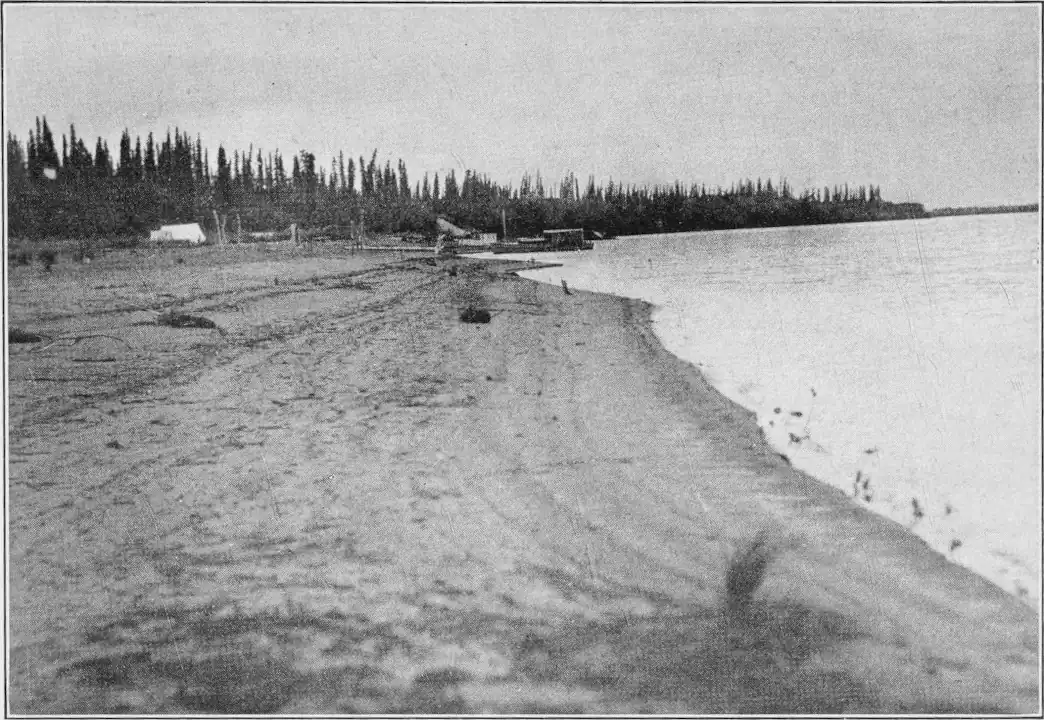

At six in the morning we sailed across Hotham Inlet and entered the Kuvak. It was wonderful weather. The sun had come out after a long spell of rain and mist; and we, who had been blockaded by ice throughout the summer, revelled in the sight of this new country, unlike any Eskimo territory we had ever seen. Here were wooded hills, fringing the fertile delta, rich grass land and soft warm breezes laden with the scent of trees and flowers.

Hotham Inlet (Imarsuk) is a big sheet of water, looking bigger than it is from the fact that the low shores are invisible until one is close upon them. Here, as throughout the whole bay, the water is so shallow that navigation is only possible by following the channels of the rivers. In rough weather, the crossing is impossible, as the water simply boils over the shallows, and parts are left high and dry.

In the course of the morning, we reached the Kuvak Delta, a big plain cut through by numerous channels, forming a maze which it would be impossible to negotiate with safety were it not for the marks set up at intervals along the fairway. The landscape seems altogether tropical to us, after the desolation of the Arctic coast. Bushes, low trees and tall grass run right out into the water, and ducks, geese and other waterfowl rise noisily as we near them. At noon we land at a little "road house" or travellers' shelter, open to any who happen to pass. It is designed more especially for winter use, and comprises, in addition to the house itself, a kennel with room for 15 dogs, a store of hay and a stack of firewood. We got a fire going in the stove, and had a meal ready in a twinkling. This disposed of, we went off up river once more. The vegetation grows richer and taller as we advance, and a couple of hours after leaving the road house we have fir trees on either side. Only a few at first, looking like forgotten Christmas trees, solitary strangers among the native birch and willow, but they soon

We reached there late that evening, and found the place well worth a visit. Three schoolmasters, an inspector, a doctor and two nurses attend to the various departments, and all are earnestly interested in the work. Everything is arranged on the most modern lines. There is a fine hospital with an operating theatre excellently equipped, and 40 beds, the whole in a two-storied building. Medical attendance and medicines are free, but patients admitted to hospital pay 75 cents per day if they can afford it. I found natives of all ages here; convalescents were admitted to the doctors' rooms and were given books, magazines and illustrated papers, besides being entertained with gramophone concerts. They seemed to be having a thoroughly good time altogether.

The Eskimos live in neat wooden houses, with electric light installed; for this, a charge of a dollar per month per house is made, the proceeds serving to pay the wages of the engineer in charge of the power station. The Eskimos have themselves defrayed the cost of the generator, the remainder being provided by the state. The place being in good timber country, a sawmill has been set up and the natives can have any quantity cut on payment in kind, a sixth of the load being the usual cost. The doctor's wife, who is herself a nurse, acts as a kind of sanitary inspector and looks after hygienic conditions in the homes. Last winter, a flag with the Stars and Stripes was offered as a prize to the housewife who kept her home in finest order. Visits of inspection were made at all hours throughout the winter in the different homes, but the lady inspector found them invariably so thoroughly washed and scoured and clean and neat that no white woman could have done better. At the end of the term, the question as to who should have the flag became a problem indeed, for all seemed equally to have deserved it. And the ingenious solution ultimately arrived at was, that it should go to the one who had most children and yet had kept her house as clean as the rest.

The white men seem to be thoroughly well in contact with the natives all round. The Inspector often goes out felling timber with them, and lives in camp among them. His wife helps the girls with their needlework, in addition to her missionary work. The doctor takes an active part in the affairs of the community apart from his own special task.

Much could be said for and against such an arrangement. Theoretically, it looks excellent, as an experiment in systematic popular education. But it is always risky to interfere overmuch in the private life of grown men and women. The Eskimos appear content with their life here so far, though they do not greatly like the automatic "lights out" at 9

We spent a day at Noorvik, and were most hospitably entertained in all the houses we visited. On the following evening we were back in Kotzebue, once more.

On the 21st of August the mailboat from Nome, a little schooner named the Silver Wave, arrived. We went on board, and found the Captain was a Norwegian, John Hegness. After a stormy voyage, we reached Nome on the 31st of August.