Across Arctic America/Chapter 26

Chapter XXVI

Cliff-Dwellers of the Arctic

Nome lies on a moist grassy plain with a fine range of fertile hills in the background, making an imposing picture to those coming from the wastes of ice and snow. My two Greenlanders gazed wide-eyed at the spectacle, impressed by the white men's power of forming great settlements far from their own country.

Thirty years ago, the population consisted of a few Eskimo families, winning a bare existence from the sea. Then, in 1900, gold was found, and as if by magic a town sprang up, with room for ten thousand souls. The haste with which it was constructed shows even now in the lack of regard for beauty or comfort. Gold was the one idea. It is said that in Nome, there is gold underfoot wherever you tread; and during the last twenty years, the district has produced over eighty million dollars. Methods at first were of the most primitive sort; men dug with spades in the sand wherever they could get at it, or stood in lines along the shore trying to wash out gold dust from the sand. Mighty machines have superseded all this, and men now prefer the certainty of a high wage regularly paid to the chance of a fortune that may never come.

The season at Nome is but short; in the first half of June the ice disappears and navigation begins; by the end of October, or early in November, the last vessel has left for the south. The summer population now is about 2000; in winter barely 900, chiefly whites; of the permanent residents hardly more than a hundred are Eskimos. The town is a sort of capital for North-west Alaska, a centre for equipment of trading expeditions, and the constant stream of people passing through in summer provides a means of existence for stores, agencies and trades of various kinds.

My companions were naturally interested in the sights of the place; the streets with their curious wood paving, and the shops with all manner of wares they had never seen before. Anarulunguaq in particular could hardly believe it was all real. After a first look round, we went into a restaurant to get something to eat. To my astonishment, we were turned out! I had forgotten that we were now in regions where people are judged by their outward appearance, and had not given a thought to our old, worn clothes. We took the hint, however, and at once set about to procure the garments of respectability; took rooms at an hotel, and arranged our mode of life on modern lines.

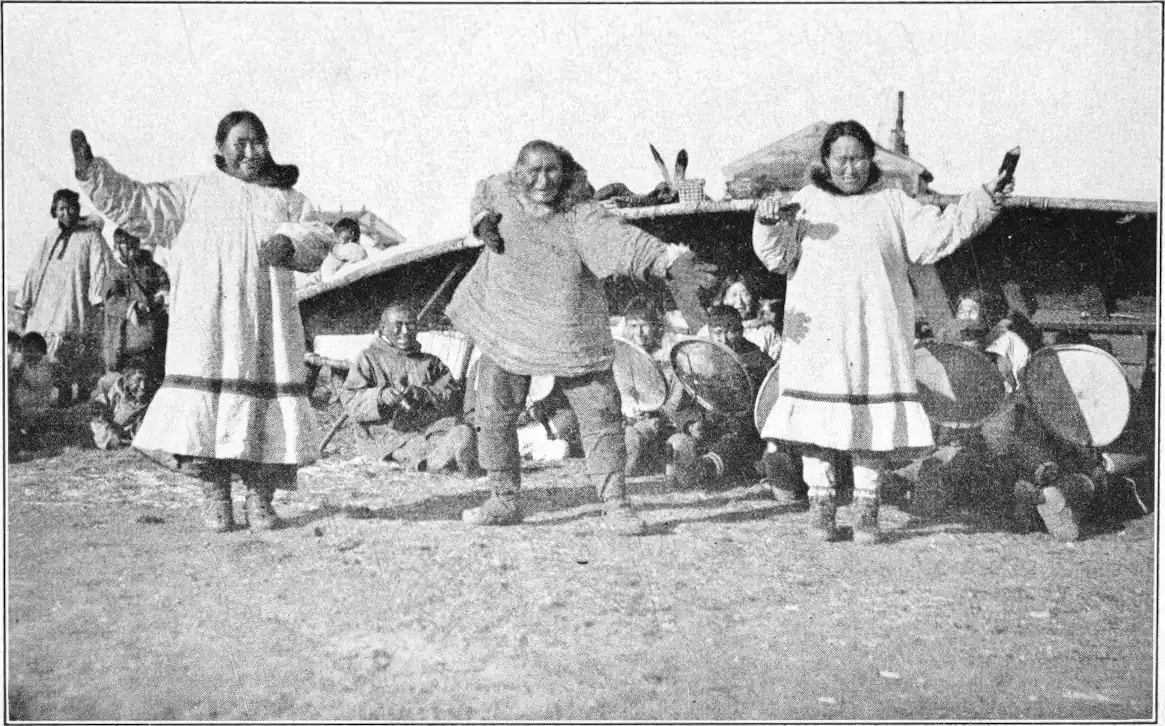

I had reached Nome at a fortunate time for my work. Here were assembled Eskimos from all parts of Alaska; the entire population of King Island, the so-called Ukiuvangmiut, the inland Eskimos from Seward Peninsula, the Qavjasamiut, the Kingingmiut from Cape Prince of Wales, the Ungalardlermiut from Norton Sound and the mouth of the Yukon, the Siorarmiut from St. Lawrence Island, and finally, natives from Nunivak Island. They had come in for the tourist season. Some lived in gold-diggers' cabins, but most of them in tents, and great camps had sprung up at either end of the town, where the Eskimos worked away making "curios," quaint carvings in walrus tusk, a form of industry which might bring in three to four hundred dollars in the course of one summer, enough to purchase necessaries for the winter with which to return home. The streets were full of Eskimos trotting about on business; they rarely, if ever, offered their wares direct for sale in the streets, but sold them to shopkeepers who retailed them. All were cleanly and decently dressed, kindly and respectful when spoken to, without the least sign of having become demoralized by life in town.

It was a festive time from first to last at Nome; an ugly little town, but a town that quickly won one's heart. It is the threshold of Alaska out towards the great adventure of the north, and the people one meets are inspired with the same love as we ourselves for that Nature which calls and enthralls. No wonder that one finds friends here. I shall always remember with especial gratitude the members of the "Lomen dynasty," who, with the splendid old Judge and his wife at their head, threw open their charming home to all the members of the Expedition, white man and Eskimo alike.

I calculated that I could afford to spend a month here, even allowing for a visit to East Cape, as the vessel which was to take us down to Seattle would not leave until the end of October. I had thus an excellent opportunity of studying the various Alaskan types without having to travel in search of them, since they were all assembled here. I have here selected two of the most distinctive, namely, the King Islanders of Bering Strait, and the natives of Nunivak Island, south of the Yukon delta.

The native myth regarding the origin of King Island is as follows:

A man from the neighborhood of Igdlo came rowing down the river in his kayak. Near Teller he sighted a giant fish, which he harpooned with a bird dart. The great fish splashed about so violently that the river overflowed its banks, forming the sheet of water now known as Imarsuk. It then swam on again, and the man pursuing harpooned it once again, when the creature in its further struggles gave rise to a new inundation, forming the bay at Port Clarence. It then swam far out to sea, the hunter followed, and at last killed it. He then cut a hole through the snout, in order to fasten a towline, but a great storm came on, and he was obliged to leave it. And there it stayed, and turned to stone, and became the island of Ukiuvak (King Island). There is a hole at one end of the island, cut right through the rock; and that is the hole which the man cut in the fish's snout.

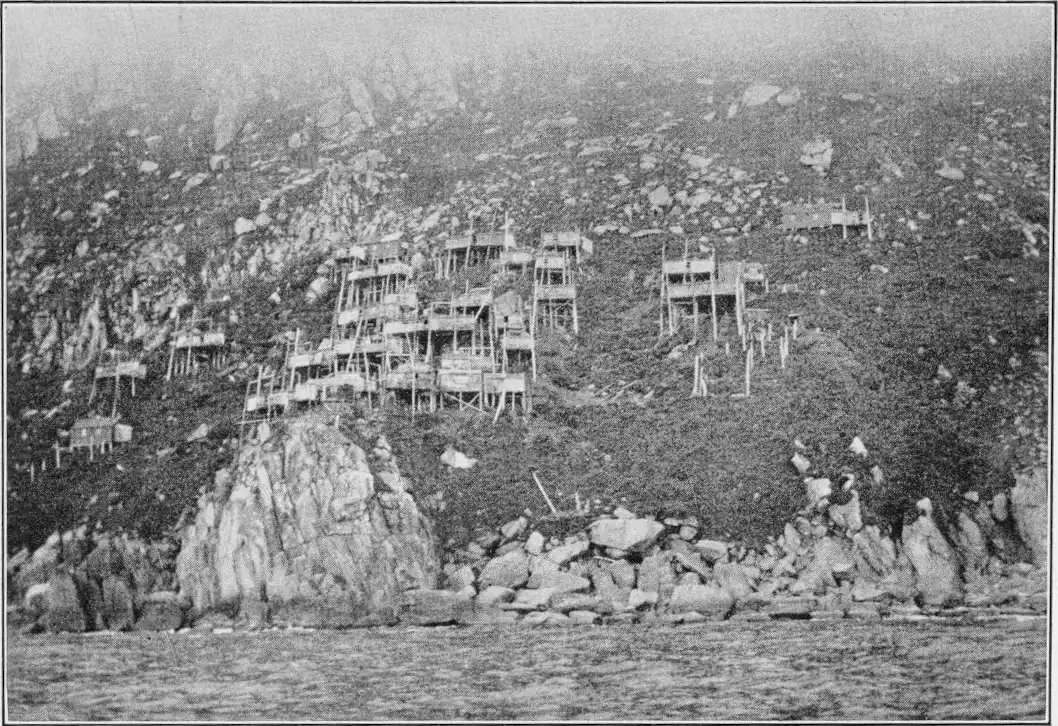

The Qavjasamiut lived in the interior, some way inland from Teller. In one of their villages there was a girl who, being scolded by her mother, ran away, and leaping on to an ice floe, was carried out to sea, and landed on King Island. She was the first human being to land there, and kept herself alive by magic; afterwards, others came over from the mainland, and a great village was formed. But the island was steep, and there were no valleys where houses could be built in the ordinary way; they had therefore to be set up on wooden supports on the steep rocky slopes. It was very cold here, with a constant wind, and the houses were built with three walls all round; first of driftwood, then a covering of hay, and over all a thick outer layer of walrus hides.

Thus the native account of King Island, its origin and colonization.

It is beyond question the most inhospitable island I have ever seen; some 3–4 km. long by 2–3 across, with steep rocky sides all round. In calm weather it is generally wrapped in fog; and when clear, harried by fierce winds, with a heavy swell that makes landing difficult among the broken rocks and churning waters at the foot of the cliffs. For a great part of the winter the place is cut off from the mainland altogether. When I visited the island, it was deserted for the time being, the entire population having gone in to Nome. We managed to land, in a small boat; and certainly it was worth a visit. It was like climbing up a bird cliff. The houses stood on piles leaning over the precipice; here and there, in the more exposed parts, the buildings were "moored" to the rock itself with ropes of plaited walrus hide. Ropes were fastened also from points on the shore up to the houses, as an aid to the ascent. Here and there one saw flat spaces under the houses themselves, where the rock had been levelled to make a playground for the children.

Notice

All property on this Island belongs to the Eskimo. Do not take or disturb anything. Failure to comply will result in arrest and prosecution.

Avlaqana,

Chief, King Island.

The King Islanders are zealous Catholics, and generally visit the Catholic Mission station at Nome during the summer. They are not only regular church-goers, but send their children to school as far as they are able, while the little ones themselves are keenly interested in their lessons. Unfortunately, there is not a single spot on the island where a school could be built. The Board of Education therefore proposed, some years back, to shift the entire population to St. Lawrence Island, where there is level ground and fertile soil; and as an inducement, each family was offered a two-years' supply of provisions, with special facilities for acquiring tame reindeer. They were invited to hold a meeting, presided over by their chief, and were given time to consider the matter. It took them very little time, however, to decide; not a single family would leave the naked rock they called their home; to them, it was the finest spot in the world.

These King Islanders are for the most part tall and well built according to Eskimo standards; they are, moreover, particularly neat and orderly with their gear. Their skin boats, kayaks, harpoons, and implements generally are the most handsomely worked in Alaska, and they have nearly always a full store of meat in reserve for the winter. Close to the village is a cave thirty metres deep, where meat will keep frozen all through the summer; it is entered through a narrow passage, and great torches have to be carried, as it is perfectly dark inside. Joints and carcases are marked with their owner's mark, the one store-chamber serving for all.

Their names for the different months of the year give an idea as to their manner of life.

October is the month of thin ice. Winter is approaching, and those who have been over to the mainland hurry back to set their house in order. The weather is unreliable, and it is dangerous to venture far out to sea. There is little hunting of seal or walrus, but fishing is carried on, mostly for small cod.

November is the hill-climbing month. The houses are built on the south side of the island, where there is now open water and very rough seas. The prevalent north wind, however, drives the ice in on the north shore; seal and walrus assemble there, and the villagers "climb the hill" to descend and go hunting on the opposite side. The yield, however, is but poor at this season.

December is the dance month. Weather stormy, and days too short for much to be done in the way of hunting; there is, however, generally a plentiful supply of meat in reserve, and the dark stormy days are passed in feasting.

January is the turning month, when the sun turns on its journey and begins to rise again. Light returns, the Strait is filled with ice and hunting commences on the north side of the island.

February is young-seal month. The seal are now heavy with young and are caught at the breathing holes and patches of open water. Sometimes the ice is firm enough for the islanders to cross to the mainland.

March is preparation month. Larger spaces of open water appear, the ice breaks adrift and kayaks and implements are made ready for use.

April is the month of getting out kayaks again. Winter hunting has now ceased altogether, the ice scatters, and the walrus begin to make their appearance. Seal and ribbon seal are harpooned from the kayak. This is the commencement of the spring season.

May is the month of flowing streams. The ground is now clear of snow and the earth "comes alive." Hunting in kayaks is continued among the drifting ice.

June is the month of light nights; game is abundant, and hunting is carried on by night and day.

July is the month of sleeping walrus, when the animals gather in great numbers on the ice and sleep in the sun, being then easily harpooned. During this and the following month most of the winter's store of meat is procured.

August is the month of fledglings. Seabirds are now caught in great numbers; many of the islanders, however, prefer to go farther afield, catching marmots for fur or gathering berries.

September is skin-forming month,—i.e., when the velvet begins to form on the antlers of the reindeer. In earlier times, the islanders went over at this season to the mainland, hunting caribou; now, however, they buy skins of tame reindeer from the owners of herds, and sell carvings and curios made during winter to the tourists at Nome.

The King Islanders are remarkably adapted to the harsh conditions under which they live, on a barren rock in the middle of the Bering Strait. They are hardy and always in training, frugal and industrious, obstinate and independent in character, and holding fast, despite their conversion to the Roman Catholic faith, to many of their ancient festivals, stories and songs. In their isolated position, with the monotony of winter on their little island, they naturally seek such diversion as can be found. Occasionally, in summer, several villages will hold great song festivals just as in the old days; and the King Islanders are famous for their dancing. There are a couple of dance houses in their village which appear to be of very ancient date. They are altogether overgrown with grass, which is so astonishingly luxuriant that it has almost filled up the chasm in which these two buildings are stuck like fantastic birds' nests. I clambered up into one of them and wormed my way through the six metres of entrance tunnel built of stones and earth; the place was hung about with tambourines and weird, staring masks—more like a temple of the spirits than a dance house. Unfortunately, there was no one on the island at the time of my visit, and I had to be content with making the acquaintance of the islanders in the picture-drome at Nome, where I found them wondering at the coldly impersonal manner in which white men go to their "festivals."

The Eskimos from the south and west of the Yukon spoke a dialect differing so considerably from the others that I found it, contrary to all previous experience, impossible to discuss difficult questions such as matters of faith and ceremonial, without the aid of an interpreter. I was fortunate in finding an excellent helper in the person of one Paul Ivanoff, a half-bred Eskimo, from St. Michael, who had also lived several years on Nunivak Island. I understood his speech without the slightest difficulty, while he also spoke the southern dialect, which is more or less the same throughout the whole range of country down to Kuskokwim and Bristol Bay.

One might expect to find the Eskimos more civilized farther to the south; this however is not the case. The Nunivak Islanders occupy a poor and barren country with clay soil, round the deltas of the great rivers; there is nothing here to attract the white man. No gold, no furs to speak of; the natives live mainly on seal and fish. Navigation is difficult along the coast here, owing to frequent storms, shallow water and lack of harbors, so that the people here have remained practically cut off from the development of the rest of Alaska. Only recently has the Bureau of Education begun to set up schools in this region, but in most places the natives are still heathen, cannot read, or even speak English. They were thus peculiarly interesting from my point of view, and I was able to procure a great deal of information as to their customs and ceremonies, in which a marked Indian influence is apparent. A notable feature in this respect is their use of masks, in which the spirit element is developed to a degree far exceeding that noted under Point Hope. There is still a belief in the very slight distinction between the animals and man, and the power of animals to take human form; hence many of the masks represent seal, or birds, or beasts of prey, with human faces. Each type is credited with some particular power, and serves to assist the angakoq in his invocation of helping spirits which here as elsewhere are the mediators between life and the supernatural.

Despite the miserable country and climate in which they live, the natives here have by no means lost their capacity for festival entertainments; on the contrary, we find here some of the prettiest ceremonies in use. When a child is born, the parents give a great feast to all those from some distance round, and old men and women are given gifts by the mother, according to her wealth and position. Every husband is expected to lay in a store of costly furs, garments and finely worked weapons and implements, to be given away at the birth feast; the birth of a child is considered so great a blessing that a man may well give away all he possesses.

Similar feasts are held for the dead, with a view to preparing the way for them and making them happy in the world beyond. The ceremonies here last a week, with various rites each day, and costly gifts to all present. As a rule several families combine in a festival for their respective dead, but even then the proceedings may be so expensive that several years of saving may be required to defray the cost of a feast worthy of the standing of the deceased.

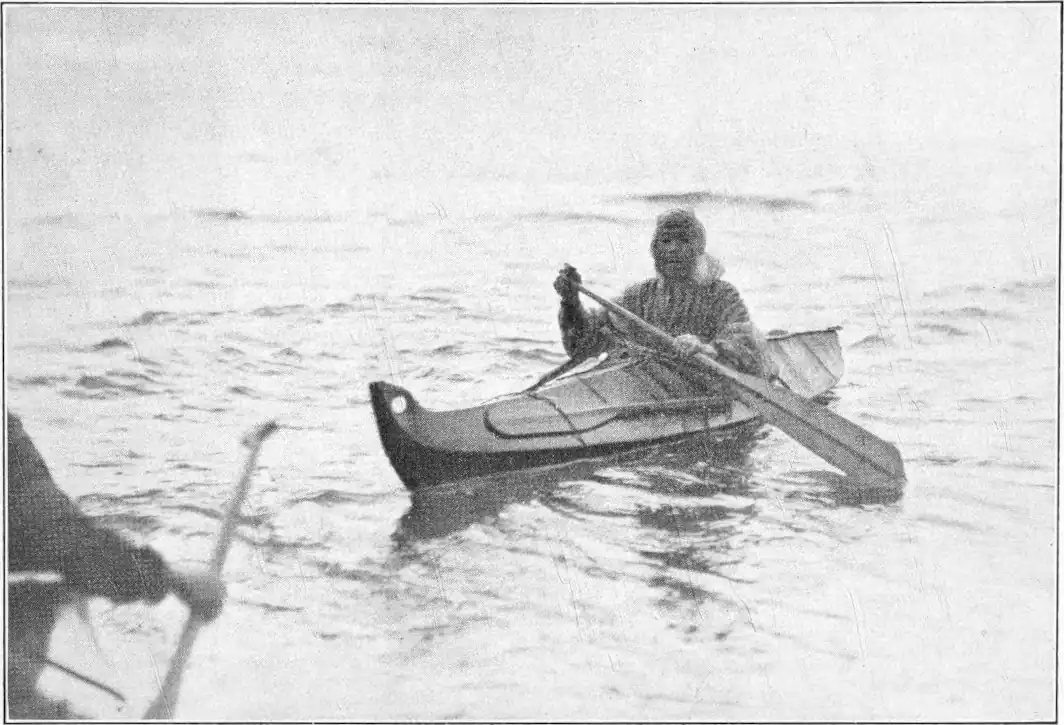

The frail kayak to which the hunter trusts himself on the sea is built with great ceremony, special rites being designed to ensure safety and good hunting. The kayak is generally renewed each year, as it is considered unpropitious to enter on a new hunting season with old gear of any sort. During the time when a man is engaged on the building of a kayak he does not enter the women's house, but remains isolated in the dance house, which is also the men's workshop. Work must be done fasting, no food being taken until the evening, when the day's work is done. All has to be done slowly and carefully, with the observance of various forms of tabu. When it is finished, the kayak is consecrated on the first fine day when the sea is calm. The whole family will appear in new clothes, man, wife and boys—girls are considered unclean. The kayak is set on the ground with all the new implements decoratively arranged in place. The ceremony takes place at dawn; the man walks in front holding a lighted lamp, and all step round the kayak, the idea being that the flame scares away all evil spirits. The man then utters these words:

"May we never neglect an opportunity of work, of procuring food."

Then he goes out hunting, and the day he brings home his first seal, with the new kayak, his wife loads up a little sledge with good food, fish, game and seal meat, and drives from house to house, giving gifts to all widows and fatherless children.

Thus gratitude should be shown for the blessing of daily food.

Every autumn a great festival is held in honor of the ribbon seal, which is an important factor in their life. The strange ceremonies here in use reveal the fundamental elements of that religious belief which we find among the Eskimos far to the east, in connection with preparation for winter work and the making of new clothes for the coming year, where strict rules of tabu must be observed.

The preparations for the festival begin in November and last a whole month. During this time the men must live apart from the women, remaining in the dance house, which their wives are only allowed to enter when bringing their food. The women, who are regarded as unclean in connection with all animals hunted, must take a bath every morning before carrying food to their husbands, and when so visiting them, must wear the waterproof garments used in stormy weather.

Every festival begins with new songs composed by the men, a kind of hymns invoking the spirits, men and women singing and dancing together. While the men are composing these hymns, all lamps must be put out, and all must be silent in the dance house, with nothing to disturb them. All males must be present, even the smallest boys, so long as they are old enough to talk. This is called the Qarrt

Here is one of the songs:

As soon as a song has been made it must be sung, and the women are called in to learn it with the rest. The making of songs, and dancing, must only be done in the evening; in the daytime, all are busy with other things; the women sewing, the men carving selected pieces of driftwood into various implements and utensils for the winter; large handsome vessels for water, drinking bowls and ladles, meat dishes and the like, so that each family has its own new set of requisites. When the men and women have finished their respective tasks, the angakoq is invited to call upon his helping spirits. He appears in new winter boots and creaking waterproof skins, and sits down in the middle of the floor. A line is brought out and a noose laid round his neck, four men hauling at each end of the rope, yet he utters his warnings and prophecies in a clear voice, despite the fact that he is apparently being strangled. Thus, almost hanging by the neck from the rope, he invokes the various animals, and informs the company when the winter hunting can begin.

As soon as this is over, the floor boards are moved away from the dance house, and a fire is lit in the space beneath. All vessels, marked with the owners' respective marks, must now be exposed to the heat of the fire, the men at the same time purifying themselves by a perspiration cure. The window in the roof is removed, the smoke escaping from the opening, yet so fierce is the heat that the men are dripping with sweat. Finally, they wash in cold water. This concludes the preparations for the great feast.

The feast itself lasts eight days. During the past year, the bladders of all ribbon seals caught have been carefully preserved, and these are now brought in to the dance house, hung up with bundles of herbs under the roof, where a harpoon and line are also fixed, with a small lamp lighted beneath them. Then with great solemnity the new clothes are put on, and the new utensils handed round to their respective owners. The women are called in, and feasts are held every day, ending with song and dance. At last, the seals' bladders are dropped into the sea through a hole in the ice, while the angakoqs implore the animals to be generous to men. On the eighth evening, men and women exchange gifts, and promise to try their best in the coming winter to be better in conduct and in their respective tasks.

The festival ends, as it began, in deep silence, the silence of good wishes and good resolutions.

And then the winter hunting can begin.

Here I conclude this description of the Alaskan Eskimos. . . . They number a little more than the Greenlanders, or about 14,000. The total number of the Eskimos is thus distributed approximately as follows: Greenland about 13,000, Canada about 5,000, Siberia about 1200—total thus about 34,000.

In material respects, the culture of the Alaskan Eskimos resembles more or less that of the natives of Point Barrow, Point Hope and on the great rivers up inland, as already described. There were of course adaptations to local conditions, but in the main, the old principles were followed throughout. Hunting on the ice is in these regions, as in the greater part of Greenland, relegated to a secondary place, and we naturally find it most highly developed in the neighborhood of the North-west Passage, where it remains the only form of seal hunting. The netting of seal, however, unknown farther to the east, is an important feature; even to this day nets are made from thin strips of sealskin and placed in narrow openings of the level ice near open water. But hunting at sea is the staple form, and is carried to a high degree of perfection. The Eskimo methods were doubtless developed on the shores of the Bering Sea, but whether this was due to the natives alone or aided by alien influence, cannot be determined with certainty.

The southern territorial limit of the Eskimos at present is on the east coast of Bristol Bay and at Kodiak in the Pacific, formerly, however, they extended as far as Prince of Wales' Sound and the coasts immediately to the southeast. Here lived also the northernmost tribes of the North-west Indians, the Tlingit, and the Eskimos here encountered a highly developed culture based on the same forms of hunting as their own. It is always possible that they may have learned something from their neighbors. This is certainly the case as regards some of their legends, especially the raven myths; also the cult of masks and the complicated ceremonial at their festivals. It is at any rate characteristic that these particular customs should have attained their highest development in these southern regions.

It is a consolation to every explorer that even the most comprehensive expedition never comes to an end, but by its researches opens the way for further work. It lies then with the future to investigate more closely the problems thus raised.