Across Arctic America/Chapter 3

Chapter III

A Wizard and His Household

I returned to headquarters on Danish Island full of excitement over the promise of my first reconnoitring expedition. Contact with these shore tribes convinced me that farther back, in the "Barren Grounds" of the American Continent I should find people still more interesting, and that our expedition would be able not only to bear to the world the first intimate picture of the life of a little known people, but also to produce evidence of the origin and migrations of all the Eskimo Tribes.

The key to these mysteries would be found in hitherto unexplored ruins of former civilizations on the shores adjacent to the Barren Grounds, and in the present-day customs of isolated aborigines who were themselves strangers alike to the white man and to the Greenland Eskimos I knew so well.

The "Barren Grounds," as they have long been called, are great tracts of bare, untimbered land between Hudson Bay and the Arctic Coast. Though forming part of the great continent of America, they are among the most isolated and inaccessible portions of the globe. It is for this reason that the most primitive and uncivilized tribes are still to be found there. Despite the zeal with which hunters and traders ever seek to penetrate into unknown regions, the natural obstacles here have hitherto proved an effective barrier, and the territory is known only in the barest outline. On the north, there are the ramifications of the Arctic Ocean, permanently filled with ice, to bar the way. On the south, and to some extent also on the west, lie great trackless forests, where travelling is slow and difficult, the only practicable route being along the little known rivers. Only from Hudson Bay has the east coast of the Barren Grounds been accessible for modern forms of transport. And even here the waters are so hampered with ice that they are reckoned to be navigable for only two or three months a year. These natural obstacles, however, which have kept others away, were all to our advantage, because they have kept the tribes of Eskimos I intended to visit uncontaminated by white civilization, imprisoned within their swampy tundras, unaltered in all their primitive character.

We were now able to plan our first year's work in these regions. Near our headquarters we found a few old cairns and rough stone shelters built by the Eskimos of earlier days for the purpose of hunting caribou with bow and arrow. We were convinced that the excavation of these ruins would be well worth while. The natives we had now met explained that these ruins originated with a mysterious race of "giants," called Tunit.

We divided up our work as follows: Mathiassen, with Kaj Birket-Smith was first to visit Captain Cleveland, to acquire preliminary information, and then Birket-Smith would travel on south, to investigate the problem of the early relations between the Indians and the Eskimos. Mathiassen's first assignment was to go with Peter Freuchen to the north, to map shores of Baffinland, and study people on whom no reliable information existed. Then, on his return, he was to excavate among the ruins we had found.

I was to study the inland Eskimos, with special reference to the spiritual side of their culture. The Eskimo members of the party were divided among the several sub-expeditions as needed, and two of them would remain on guard at the headquarters camp.

We had a pretty good supply of pemmican, both for ourselves and for the dogs, as well as canned goods, which would form the basis of our provisions. We had to supplement it, however, with fresh meat. We were told that Cape Elizabeth, toward the north, was a good spot for walrus at this time of year, and I therefore went off with Miteq and two of the local natives to try our luck. We set out on the 11th of January. Despite some difficulty, owing to snow, which drifted thickly at times, we had some exciting caribou hunting on the ice during the first two days. The thermometer stood at about minus 50 C. (63 F.) and every time we picked up our guns with the naked hand the cold steel took the skin off.

We purchased some stores of meat at Lyon Inlet, and devoted a few days to fetching these, after which we set out again to the Northward to find the village. None of us knew exactly where it was, as the natives had not yet moved down to the coast, but were encamped some way inland where they had been engaged on their autumn caribou hunting.

The 27th of January was fine, but cold; it was bright starlight towards the close of the journey, but we had had a long and tiring day, and wished for nothing better than to find shelter without having to build it ourselves.

Suddenly out of the darkness ahead shot a long sledge with the wildest team I have ever seen. Fifteen white dogs racing down at full speed, with six men on the sledge. They came down on us at such a pace that we felt the wind of them as they drew alongside. A little man with a large beard, completely covered with ice, leapt out and came towards me, holding out his hand white man's fashion. Then halting, he pointed inland to some snow huts. His keen eyes were alight with vitality as he uttered the ringing greeting: "Qujangnamik" (thanks to the coming guests).

This was Aua, the angakoq.

Observing that my dogs were tired after their day's run, he invited me to change over to his sledge, and quietly, but with authority, told off one of the young men in his party to attend to mine. Aua's dogs gave tongue violently, eager to be off again and get home to their meal; and soon we were racing away towards the village. A brief dash at breakneck speed, and we arrived at the verge of a big lake, where snow huts with gut windows sent out a warm glow of welcome.

The women came out to greet us, and Aua's wife, Orulo, led me into the house. It was, indeed, a group of houses, cleverly built together, a real piece of architecture in snow, such as I had never yet seen. Five huts, boldly arched, joined in a long passage with numerous storehouses built out separately, minor passages uniting one chamber with another, so that one could go all over the place without exposure to the weather. The various huts thus united served to house sixteen people in all. Orulo took me from one to another, introducing the occupants. They had been living here for some time now, and the heat had thawed the inner surface of the walls, forming icicles that hung down gleaming in the soft light of the blubber lamp. It looked more like a cave of stalactites than an ordinary snow hut, and would have looked chilly but for the masses of thick, heavy caribou skin spread about.

Through these winding passages, all lit with tiny blubber lamps, we went from room to room, shaking hands with one after another of the whole large family. There was Aua's eldest son Nataq, with his wife, and the youngest son Ijarak who lived with his fifteen-year-old sweetheart; there was Aua's aged sister Natseq with her son, son-in-law and a flock of children; and finally, out in the farthest end of the main passage, the genial Kuvdlo with his wife and a newborn infant.

It was the first time I had visited so large a household, and I was much impressed by the patriarchal aspect of the whole. Aua was unquestioned master in his own house, ordering the comings and goings and doings of all, but he and his wife addressed each

Hot tea, in unlimited quantity, was welcome after our long hours in the cold, and this being followed by a large, fat freshly cooked hare, it was not long before appetite gave way to ease, and we settled ourselves comfortably among the soft and pleasant smelling caribou skins.

We explained that we had come down to hunt walrus, and the news was greeted with acclamation by our host and his party. They had been thinking of doing the same themselves, and it was now suggested that the whole village should move down to some snowdrifts on the lowlying land at Cape Elizabeth. They had been hunting inland all the summer, and there were numerous good meat depots established in the neighborhood. There was oil enough to warm up the houses for a while, but the last bag of blubber had already been opened. We decided therefore to go hunting on the ice. It was necessary first of all, however, to spend one day in fetching in stores of caribou meat from the depots, as there was no saying how long it might be before we procured any other.

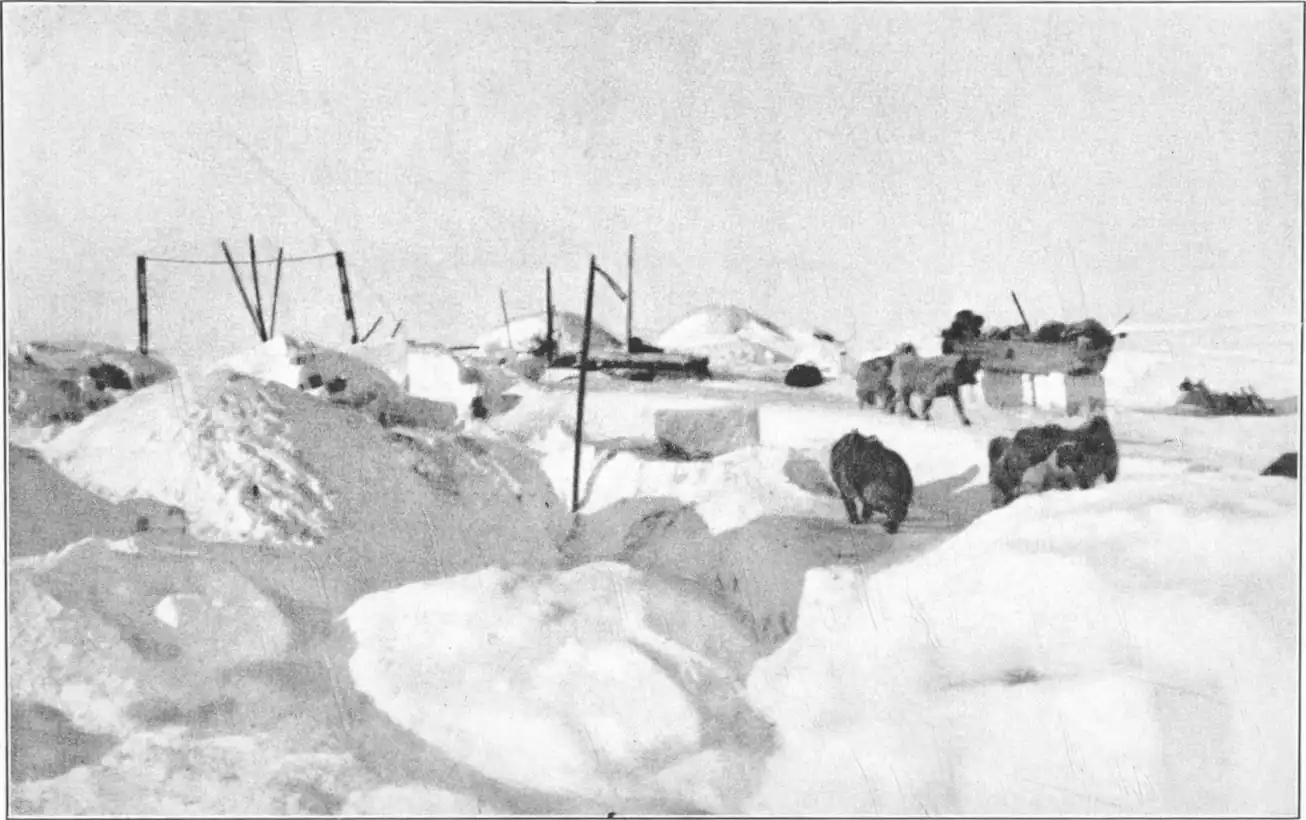

On the day of the final move, all were up betimes and busily at work. Pots and dishes and kitchen utensils generally were trundled out through the passages, with great bales of caribou skins, some new and untouched, others more or less prepared, and huge unwieldly bundles of clothing, men's, women's and children's. The things had not seemed to take up much room within doors, where everything had its place and use, but the whole collection stacked outside in the open air looked as cumbrous and chaotic, as unmistakably "moving" as the worldly goods of any city and surburban family waiting on the pavement for the furniture van.

Just at the last moment, when the sledges were loaded up to the full, and the teams ready to start, I had the good fortune to witness a characteristic little ceremony; the initiation of an infant setting out on its first journey into the world.

An opening appeared somewhere at the back of Kuvdlo's house, and through it came crawling Mrs. Kuvdlo with the little new-born infant in her arms. She planted herself in front of the hut and stood waiting until Aua appeared. Aua, of course, was the spiritual shepherd of the flock. He stepped forward towards the child, bared its head, and placing his lips close to its face, uttered the following heathen equivalent of a morning prayer:

It was the child's first journey, and the morning hymn was a magic formula to bring it luck through life.

The winter ice extends some miles out from the shore, to all intents and purposes as firm as land. Then comes the water, with pack ice drifting this way and that according to wind and current. When the wind is blowing off shore, holes appear in the ice just at the edge, and the walrus follow these, diving down to the bottom to feed.

Aua and I had settled ourselves, like the others, in comparative shelter behind a hummock of ice, with a good view all round. The vigil was by no means monotonous; there was something going on all the time, calling up memories of past hunting. The pack ice was in constant movement, surging and straining and groaning at every check. Now and then a gap would appear, and the naked water sent up a freezing mist like blue smoke, through which we could just discern the black shapes of the walrus rising to breathe. We could hear their long, slow gasp—and then down they went to their feeding grounds below.

We had both experienced it all many a time before; and the familiar sights and sounds loosened our tongues in recollection.

"Men and the beasts are much alike," said Aua sagely. "And so it was our fathers believed that men could be animals for a time, then men again." So he told the story of a bear he had once observed, hunting walrus like a human being, creeping up and taking cover, till it got within range, when it flung a huge block of ice that struck its victim senseless.

Then suddenly Aua himself gave a start—he had been keeping a good look out all the time—and pointed to where Miteq was standing with his harpoon raised. Just ahead of him was a tiny gap in the ice, the merest puddle, with barely room for the broad back of a walrus that now appeared. Miteq waited till the head came up, and then, before the creature had time to breathe, drove his harpoon deep into the blubber of its flank. There was a gurgle of salt water, a fountain of spray flung out over the ice, and the walrus disappeared. But Miteq had already thrust his ice-axe through the loop at the end of his harpoon line, and the walrus was held.

We hurried up and helped to haul it in, despatched it, and set about the work of cutting up. This was completed before dark, and when we drove in that night to the new snow palace at Itibleriang, I was proud to feel that one of my own party had given these professionals a lead on their own ground.

There was great rejoicing at our arrival; a full-grown walrus means meat and blubber for many days, and this was the first day we had been out. There was no longer any need to stint the blubber for the lamps, and there was food in plenty for ourselves and the dogs.

A well-stocked larder sets one's mind at rest, and one feels more at liberty to consider higher things. Also, our surroundings generally were comfortable enough. The new snow hut was not quite as large as the former, and lacked the fantastic icicle adornment within; but it was easier to make it warm and cosy. The main portion, the residence of Aua and his wife, was large enough to sleep twenty with ease. Opening out of this, through a lofty portal, was a kind of entrance hall, where you brush off the snow before coming in to the warmth of the inner apartment. On the opposite side again was a large, light annex, accommodating two families. As long as there was blubber enough, seven or eight lamps were kept burning, and the place was so warm that one could go about half naked and enjoy it.

Which shows what can be made out of a snowdrift when you know how to go about it.

Aua gave me leave to ask questions, and promised to answer them. And I questioned him accordingly, chiefly upon matters of religion, having already perceived that the religious ideas of these people must be in the main identical with those of the Greenland Eskimo.

A prominent character in the Greenland mythology is the Mistress of the Sea, who lives on the floor of the ocean. I asked Aua to tell me all he could about her. Nothing loath, he settled himself to the task, and with eloquent gestures and a voice that rose and fell in accord with the tenor of his theme, he told the story of the goddess of meat from the sea.

Briefly, it is as follows: There was once a girl who refused all offers of marriage, until at last she was enticed away by a petrel disguised as a handsome young man. After living with him for some time, she was rescued by her father, but the petrel, setting out in pursuit, raised a violent storm, and the father, in terror, threw the girl overboard to lighten the boat. She clung to the side, and he chopped off, first the tips of her fingers, then the other joints, and finally the wrists. And the joints turned into seal and walrus as they fell into the sea. But the girl sank to the bottom, and lives there now, and rules over all the creatures of the sea. She is called Takanaluk Arnaluk; and it is her father who is charged with the punishment of those who have sinned on earth, and are not yet allowed to enter the land of the dead.

I enquired then as to this land of the dead, and the general arrangements for their after-life. This falls mainly into two parts.

When a human being dies, the soul leaves the earth, and goes to one or the other of two distinct regions. Some souls go up into heaven and become Uvdlormiut, the People of Day. Their country lies over towards the dawn. Others again go down under the sea, where there is a narrow belt of land with water on either side. These are called Qimiujarmiut, the People of the Narrow Land. But in either place they are happy and at ease, and there is always plenty to eat.

Those who pass to the Land of Day are people who have been drowned, or murdered. It is said that the Land of Day is the land of glad and happy souls. It is a great country, with many caribou, and the people there live only for pleasure. They play bali most of the time, playing at football with the skull of a walrus, and laughing and singing as they play. It is this game of the souls playing at ball that we can see in the sky as the northern lights.

The greater among the angakoqs, or wizards, often go up on a visit to the People of Day, just for pleasure. Such are called Pavungnartut, which means, those who rise up to heaven. The wizard preparing to set out on such a journey is placed at the back of the bench in his hut, with a curtain of skin to hide him. from view. His hands must be tied behind his back, and his head lashed fast to his knees; he wears breeches, but nothing more, the upper part of his body being bare. When he is thus tied up, the men who have tied him take fire from the lamp on the point of a knife and pass it over his head, drawing rings in the air, and saying at the same time: "Niorruarniartoq aifale" (Let him who is going on a visit now be carried away).

Then all the lamps are extinquished, and all those present close their eyes. So they sit for a long while in deep silence. But after a time strange sounds are heard about the place; throbbing and whispering sounds; and then suddenly comes the voice of the wizard himself crying loudly:

"Halala—halalale halala—halalale!"

And those present then must answer "ale—ale—ale." Then there is a rushing sound, and all know that an opening has been made, like the blowhole of a seal, through which the soul of the wizard can fly up into heaven, aided by all the stars that once were men.

Often the wizard will remain away for some time, and in that case, the guests will entertain themselves meanwhile by singing old songs, but keeping their eyes closed all the time. It is said that there is great rejoicing in the Land of Day when a wizard comes on a visit. The people there come rushing out of their houses all at once; but the houses have no doors for going in or out, the souls just pass through the walls where they please, or through the roof, coming out without making even a hole. And though they can be seen, yet they are as if made of nothing. They hurry towards the newcomer, glad to greet him and make him welcome, thinking that it is the soul of a dead man that comes, and one of themselves. But when he says "Putdlaliuvunga" (I am still a creature of flesh and blood) they turn sorrowfully away.

He stays there awhile, and then returns to earth, where his fellows are awaiting him, and tells of all he has seen.

The souls that pass to the Narrow Land are those of people who died of sickness in house or tent. They are not allowed to go straight up into the land of souls, because they have not been purified by violent death; they must first go down to Takanalukarnaluk under the sea, and do penance for their sins. When all their penance is completed, then they go either to the Land of Day or stay in the Narrow Land, and live there as happily as those who are without sin.

The Narrow Land is not like the Land of Day; it is a coast land, with all manner of sea creatures in abundance, and there is much hunting, and all delight in it.

I enquired whether the wizards did not make other excursions into the supernatural, for some special purpose. Aua informed me that this was the case, and kindly gave me further details.

Should the hunting fail at any season, causing a dearth of meat, then it is the business of the Angakoq to seek out the Mistress of the Sea and persuade her to release some of the creatures she is holding back. The preparations for such a journey are exactly the same as in the case of a visit to the Land of Day, already described. The wizard sits, if in winter, on the bare snow, in summer, on the bare earth. He remains in meditation for a while, and then invokes his helping spirits, crying again and again:

"Tagfa arqutinilerpoq—tagfa neruvtulerpoq!" (The way is made ready for me; the way is opening before me.)

Whereupon all those present answer in chorus: "Taimalilerdle" (let it be so).

Then, when the helping spirits have arrived, the earth opens beneath the wizard where he sits; often, however, only to close again; and he may have to strive long with hidden forces before he can finally cry that the way is open. When this is announced, those present cry together: Let the way be open, let there be way for him! Then comes a voice close under the ground: "halala—he—he—he" and again farther off under the passage, and again still farther and ever farther away until at last it is no longer heard; and then all know that the wizard is on his way to the Mistress of the Sea.

Meantime, those in the house sing spirit songs in chorus to pass the time. It may happen that the clothes which the wizard has taken off come to life of themselves, and fly about over the heads of the singers, who must keep their eyes closed all the time. And one can hear the sighing and breathing of souls long dead. All the lamps have been put out, and the sighing and breathing of the departed souls is as the voice of spirits moving deep in the sea; like the breathing of sea-beasts far below.

One of the songs is a standing item on these occasions; it is only to be sung by the elders of the tribe, and the text runs thus:

Great wizards find a passage opening of itself for their journey down under the earth to the sea, and meet with no obstacles on the way. On reaching the house of Takanalukarnaluk, they find a wall has been built in front of the entrance; this shows that she is hostile towards men for the time being. The wizard must then break down the wall and level it to the earth. The house itself is like an ordinary human dwelling, but without a roof, being open at the top so that the woman seated by her lamp can keep an eye on the dwellings of men. The only other difficulty which the wizard has to encounter is a big dog which lies stretched across the passage, barring the way. It shows its teeth and growls, impatient at being disturbed at its meal—for it will often be found gnawing the bones of a still living human being. The wizard must show no sign of fear or hesitation, but thrust the dog aside and hurry into the house. Here he meets the guardian of the souls in purgatory, who endeavors to seize him and place him with the rest, but on stating that he is still alive: "I am flesh and blood," he is allowed to pass. The Mother of the Sea is then discovered seated with her back to the lamp and to the animals gathered round it—this being a sign of anger—her hair falls loose and dishevelled over her face. The wizard must at once take her by the shoulder and turn her face the other way, at the same time, stroking her hair and smoothing it out. He then says:

"Those above can no longer help the seal up out of the sea."

To which she replies: "It is your own sins and ill doing that bar the way."

The wizard then exerts all his powers of persuasion, and when at last her anger is appeased, she takes the animals one by one and drops them on the floor. And now a violent commotion arises, and the animals disappear out into the sea; this is a sign of rich hunting and plenty to come.

As soon as the wizard returns to earth, all those in the house are called upon to confess any breach of tabu which they may have committed.

All cry out in chorus, each eager to confess his fault lest it should be the cause of famine and disaster to all. And in this way "much is made known which had otherwise been hidden; many secrets are told." But when the sinners come forward weeping and confess, then all is well, for in confession lies forgiveness. All rejoice that disaster has been averted, and a plentiful supply of food assured; "there is even something like a feeling of gratitude towards the "sinners" added Aua naïvely.

I enquired whether all wizards were able to accomplish such an errand, and was informed that only the greatest of them could do so. One of the greatest angakoqs Aua had known was a woman. And he told us the story of Uvavnuk, the woman who was filled with magic power all in a moment. A ball of fire came down from the sky and struck her senseless; but when she came to herself again, the spirit of light was within her. And all her power was used to help her fellows. When she sang, all those present were loosed from their burden of sin and wrong; evil and deceit vanished as a speck of dust blown from the hand.

And this was her song:

All had listened so intently to Aua's stories of the supernatural that none noticed the women had neglected their duty, and the lamps were almost out. It was indeed an impressive scene; men and women sat in silence, hushed and overwhelmed by the glimpses of a spirit world revealed by one of its priests.

By the 14th of February, our whole party was assembled at Itibleriang. The Baffin Land party were to stay on for a few days more, walrus hunting; the rest of us, who were going south, split up into detachments; Miteq and Anarulunguaq went with me. Birket-Smith and Bangsted were also with us most of the way.

On a fine sunny morning then—February 16—we waved goodbye to our comrades and set off homewards. This is the first time since leaving Denmark that we have been separated for any long or indefinite period, and there is much important work to be done in the eight months which must elapse before we meet again.

After three cold days on the road, and warm nights in comfortable snow huts, we reached home in a gale of wind that is no discredit to this windy region. So dense was the whirling snow that the whole of the last day's journey was accomplished with bent. backs and bowed heads; we had literally to creep along, following the well-worn sledge track with our noses almost to the ground. It was the only way we could be sure of crossing Gore Bay from Qajugfit without missing the little island that was our goal. When at last we got in, our faces were completely coated with ice, all save two small gaps round the eyes that just enabled us to see. Oddly enough, however, we had no feeling of cold; possibly the exertion, with our heavy skin garments, had kept us warm, or perhaps the Eskimos are right in declaring that "heat comes out of the earth" in a blizzard.