Across Arctic America/Chapter 4

Chapter IV

Finger-Tips of Civilization

Our route lay southward, to the country of the inland Eskimos of the Barren Grounds, with Chesterfield, the "Capital" of Hudson Bay, as our first objective.

A last farewell, and off we went, the dogs giving tongue gaily as they raced away. We followed the old familiar high road down to Repulse Bay. We were anxious to make the most of each day's run while the dogs were still fresh, and intended therefore to make but a short stay at Captain Cleveland's. Actually, however, matters turned out otherwise. A blizzard from the north-west whirled us down to his place, and kept on for three days in a flurry of snow that made it impossible to see an arm's length ahead.

At last, when the storm had thrashed itself out, we made ready to push on. Our loads weighed something like 500 kilos per sledge, and ran heavily. We had reckoned, at starting, to make do with the iron runners, as generally used in Greenland, but the first day's journey showed that they dragged in the snow to such a degree that the pace was of the slowest, and would soon spoil the temper of the dogs. We had therefore, while at Cleveland's, had recourse to ice-shoeing, a great improvement on the naked iron, and a triumph of Eskimo invention. The process is complicated, and should be described in detail.

As long as the snow is moist, and the air not too cold, iron or steel runners make quite good going. But as soon as the thermometer falls below 20° C, they begin to stick, and the colder it gets, the worse it is. The cold makes the snow dry and powdery, until it is like driving through sand, the runners screeching and whining with the friction, so that even light loads are troublesome to move. The Eskimos of earlier days of course knew nothing of iron runners, but made shift with a patchwork of walrus tooth, whalebone or horn, cut and smoothed to fit, and lashed under the sledge. These runners acted then exactly as does the iron.

It had, of course, been observed that ice ran easiest over snow, and obviously it would be an advantage to give the runners a coating of ice. But this was not so easy to begin with. Ice would not hold on iron or steel, bone or wood. Ultimately, someone hit on the idea of coating the runners first of all with a paste made from peat softened in water, and laying a thin coat of ice on after. This method at once proved eminently successful, and has remained unsurpassed for rapid running with heavy loads, despite. numerous experiments made with other materials by various expeditions. It has, however, the disadvantage of being a lengthy and difficult process in its application.

The first requisite is to find the peat; or failing this, lichen or moss. The mass should in any case be entirely free from sand or grit. It has then to be thawed, crumbled in the hands, mixed with tepid water and kneaded to a thick paste which is spread on the runners in the form of a ski, broadest in front just where the runners curve upward. Even in very severe cold it requires a day to freeze thoroughly on, and not until then can the coating of ice be applied. This is done by smearing it with water, using a brush or a piece of hide. The water must be lukewarm, as the sudden cooling gives a harder and more durable form of ice. With this shoeing, even a heavily laden sledge will take quite considerable obstacles, as long as the movements are kept fairly smooth, avoiding any sudden drop that might crack the coating of ice. Should this occur, it is a troublesome business to repair it. In the course of a long day's journey, the ice gets worn through, and has to be renewed once or twice; it is therefore necessary to carry water, in order to save the loss of time occasioned by first melting snow or ice.

With a good ice shoeing and reasonably level ground, even heavy loads will run as smoothly as in a slide, without fatiguing the teams.

It was hopeless, of course, to go out in the blizzard hunting for peat, so we had recourse to another means in this case. Mr. Cleveland had plenty of flour at the store; we purchased some of this, and worked it up with water into a dough which proved excellent for the purpose. And lest any should consider it a sinful waste of foodstuffs in a region ill provided with the same, I may reassure my readers

We were rather late in starting, and got no farther that day than a camp of snow huts on the western side of Repulse Bay. Here we were kindly received by an old couple who had settled down on the spot with their children and nearest of kin. On entering their hut, we found, to our astonishment, rosaries hung above the blubber lamps and crucifixes stuck into the snow walls. Our host, divining the question in our minds, explained at once that he had met a Roman Catholic missionary far to the south some. time before, and had been converted with all his family. He had formerly been an angakoq himself; and it was plain to see that he was an honest man, earnestly believing in his powers and those he had invoked. But, he informed us, from the moment he first listened to the words of the stranger priest, his helping spirits seemed to have deserted him; doubt entered into his mind, he felt himself alone and forsaken, helpless in face of the tasks which had called forth his strength in earlier days. At last he was baptized, and since then, his mind had been at rest. All his nearer relatives had followed his example, and all now seemed anxious to make us understand that they were different from the ordinary heathen we had met. The others of their tribe had given them the name of Majulasut, which means, they who crawl upward, as indicating that they had already relinquished their foothold upon earth, and sought only to find release from the existence to which they were born.

We started early the next morning, there was a broad spit of land to cross at Beach Point, and we were eager to see how our ice shoeing took it. The pace was good enough; but we had hardly begun to congratulate ourselves on this before we discovered that what we had gained for the dogs we had lost for ourselves. Travelling overland in Greenland is quite good fun for the most part, and little obstacles need not be taken too seriously; the iron runners will take no harm from an occasional stone or point of rock. Here, however, we have to leap off at the first sight of any such hindrance ahead, and guide the sledge carefully to avoid damage to the fragile covering of ice. Save for this, however, the general result is admirable. The sledges glide as if their heavy loads were feather light, and we can keep at a sharp trot all day, despite the hilly going. It is a pleasure to see how little exertion is required on the part of the dogs; the sledges run almost by themselves, with just a momentary pull every now and again.

We halted that night on the edge of a lake, and built a snow hut for shelter.

It was a cheerless country we were driving through. Everything one saw was like everything else; today's journey was just yesterday's over again; no mountains, only small hills, lakes and level plain.

Next afternoon, to our great surprise, we met a fellow traveller on the road. A sledge appeared in the distance, coming straight towards us, and shortly after we had the pleasure of a first encounter with the famous Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Both sledges halted as we came together, and a tall, fair young man came forward and introduced himself as Constable Packett, of the Mounted Police Headquarters at Chesterfield Inlet, on his way out to inspect our station.

It was strange to us to meet with police in these regions; and we were at once impressed by the energy with which Canada seeks to maintain law and order in the northern lands. The mounted police, a service popular throughout the country, has here to relinquish its splendid horses and travel by dog sledge, making regular visits of inspection over a wide extent of territory. Originally, the headquarters here was at Cape Fullerton, a couple of days' journey northeast of Chesterfield; the whaling vessels used to winter there, and the somewhat mixed society of the whaler's camp required a good deal of looking after. The whaling has now ceased, but the Mounted Police remains as a permanent institution in the Canadian Arctic, representing the Government of the country and its laws, in regard to white men and Eskimos alike.

I explained to Constable Packett that he would find Bosun's wife and some of our Eskimos at the station; and recognizing that I could not go back with him myself without giving up the journey I had planned, he very kindly agreed to make do with a report, which I promised to hand in at Chesterfield, instead of requiring my personal attendance. He himself, however, would have to go on to our headquarters, in accordance with his instructions.

I confess to being somewhat impressed by the Canadian Mounted Police as undaunted travellers. Our friend here, for instance, was out for a little run of some two thousand kilometres. He reckoned to be two and a half months on the way, and during the whole of that time, he would have no shelter but a snow hut, save for the few days at Captain Cleveland's and our station. We bade him a hearty farewell, and were soon out of sight.

At noon on the 3rd of April we came up with the icebound vessel Fort Chesterfield at Berthie Harbor, a little to the north of Wager Bay. Despite all good resolutions as to not breaking the journey while it was light enough to see, we found it impossible to pass by these cheery seamen's door without a halt. Captain Berthie himself was away, investigating the possibilities of some new harbor works. I had met him before, and spent some days with him on the road. Berthie had all the good qualities of the French Canadian, and in addition, was thoroughly familiar with all forms of travel in the Arctic, and speaks Eskimo fluently. His crew, consisting exclusively of young men from Newfoundland, were full of praise for their captain; and entertained us in his absence with cheerful hospitality. A little village of immigrant Netsilik natives had sprung up about the vessel, and I took the opportunity of paying them a visit. The oldest inhabitant was an aged veteran from the region of the North Pole, named Manilaq. He had been a great fighter in his day, but was now reduced to resting on his laurels. He lived in a big snow hut with his children and grandchildren, who still regarded him with great respect, treating him indeed, as if he were their chief. He was an excellent story-teller, and always sure of a large audience. Unfortunately, I had not time myself to draw upon his stock of folk lore and personal recollections. It was essential to my plans that we should get as far on into the Barren Grounds as possible while the winter lasted. I hoped, however, to have an opportunity of meeting the old fellow later. As it turned out, this was not to be. A little while after we had left, he committed suicide, in the presence of his family, preferring to move to the eternal hunting grounds rather than live on growing feebler under the burden of days.

The time passed rapidly now, and our sole object was to get on as far as possible. We took short cuts wherever we could, though travelling overland was always an anxious business, unaccustomed as we were at first to the use of this delicate ice-shoeing. Thus we cut across the flat country from Berthie Harbor due west down to Wager Inlet; the mouth of the great fjord here is never frozen over, owing to the strength of the current. From here we came up on land again, and at last, on the 10th of April, reached Roe's Welcome, at a bay called Iterdlak. We could now follow the coast right down to Chesterfield, and though the country itself was very monotonous, there was plenty to interest us here. Every time we rounded a headland we came upon the ruins of some old settlement, which were eagerly investigated. They were not the work of the present population, but of some earlier inhabitants, evidently of a high degree of culture and well up in stone architecture. The ruins consisted of fallen house walls, store-chambers, and tent rings-all of stone-with frameworks for kayaks and umiaks, such as one finds in Greenland, where the boats are set up to keep the skins from being eaten by the dogs. There was evidence of abundant hunting by sea, in the form of numerous bones scattered about wherever the ground lay free from snow. Meat cellars were also frequently found, and to judge from their size, there should have been no lack of food. Every little headland was fenced in by stone cairns placed so close together that they looked from a distance like human beings assembled to bid us welcome. They were set out along definite lines across the ground, and had once been decked with fluttering rags of skin on top, serving to scare the caribou when driven down to the coast, where the hunters lay in wait in their kayaks, ready to spear them as soon as they took to the water.

All these ruins were the work of the "Tunit"; and from all that we could see, this highly developed coastal race with their kayaks and umiaks, must have been identical with the Eskimos that came into Greenland from these regions a thousand years ago. Both Miteq and Arnaruluk felt thoroughly at home in these surroundings. Much of what they had met with among the living natives of the present day was strange to them, but these relics of the dead from a bygone age were such as they knew from their own everyday life at home.

We followed the coast southward, keeping close in to shore, as the ice here was good and level. On the 16th of April we passed Cape Fullerton, where some empty buildings still remain from the great days of the whaling camps. It was late in the afternoon, and the sun shone warmly over the spit of land, as if in welcome. It was tempting; here we could find shelter in a real house if we wished; but we had heard that there were natives at Depot Island, and our eagerness to meet them outweighed considerations of mere creature comfort. We drove on, therefore, until the twilight forced us to camp on the site of a famous ruin, known as Inugssivik. It had evidently been a big village at one time, and the huge stones that had been placed in position showed that the folk who lived there were not afraid of hard work. Our guide, Inujaq, informed us that in the olden days, there was always war between these people here and the tribes from Repulse Bay; hostilities had continued throughout a number of years, until the villagers here had been entirely exterminated.

Next morning, as soon as it was fully light, we perceived a small hillock far to the south amid the ice. This was Depot Island, which juts up out of the great white expanse like the head of a seal come up to breathe. It was some distance away, but we hoped to reach it before dark. We have given the dogs an easy time lately, and it would do them no harm to let them know we were in a hurry. A good driver should have the power of communicating his feelings to his team, so that the animals feel his own eagerness to get forward in case of need. And it was not long before our dogs realized that the old steady jogtrot would not do today; something more was needed. And accordingly, they were soon at full gallop; the sledges, lightened of all the dog-feed we had used up since leaving Repulse Bay, flew over the ice at such a pace that the occasional jerks at the traces threw them sideways on, and us nearly off. A little after noon we reached the island, having covered the distance at an average speed of ten kilometres an hour.

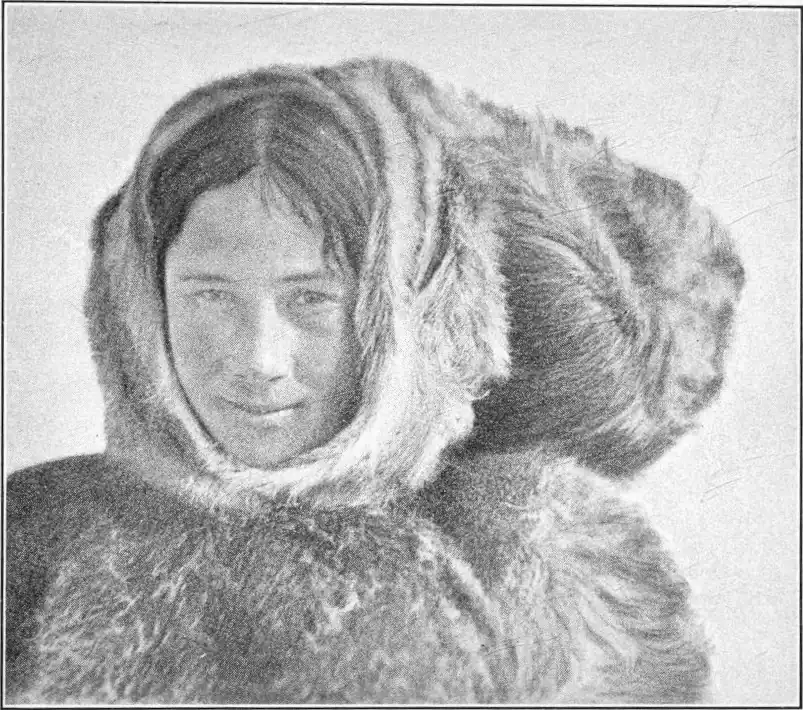

It was not long before we came upon fresh sledge tracks, and following them down to the coast, drove across a little headland without sighting any human being. Then suddenly we almost fell down a steep incline, and dashed full into a cluster of snow huts half buried in loose snow. Wooden frames stood up here and there, with skins and inner garments hung out to dry or bleach; two fat dogs came out and started barking—here evidently was the place we had been seeking. Miteq ran up to the window and shouted down to those within: "Here we are; here we are at last," a piece of mischievous fun that brought out the inmates at once. There was a confusion of cries and shouting, as of women in a flutter, a sound of rapid steps along the passage way, and out among us tumbled—a black girl. A little negro lady as black as one could wish to see.

This was perhaps the most surprising encounter we have experienced up to date. I noticed also, that the sight was almost too much for Miteq, who started back and stood with wide eyes fixed in wonder on the unexpected figure. Here we were come all the way from Greenland to seek out other peoples of the farthest northern lands; and all of a sudden we found ourselves face to face with a child of the tropic South; a creature of the sun leaping up out of the snow!

The girl herself was no less astonished at our appearance. She retreated hastily into the hut, and we stood there waiting in eager anticipation until steps once more were heard within, and the girl reappeared, this time in company with three older women of normal Eskimo type.

It is often almost a pity to have mysteries explained; the whole thing seems so natural once you know how it came about, that there is nothing marvellous or thrilling about it afterward. The oldest of the women came up to us at once and asked who we were. When we had introduced ourselves as lucidly as possible, she explained that her husband and those of the other two women were out hunting, but should be back in the course of the day. She named her companions one by one, and when it came to the dark young lady's turn, informed us that this was her daughter by a stranger, a man who had come to them from a land where it was always summer. A remarkable man, she explained, one who never went out hunting himself, but devoted his life to the task of preparing rare feasts and luscious dishes for his fellows. He had come to their country on a great ship, and had spent the winter in their huts.

It was all simple enough after this. The girl's father had been a negro cook on one of the American whalers.

The dwelling place consisted of three large roomy huts, built together. The party here had spent the summer and autumn inland, caribou hunting, and had moved out in the course of the winter for the walrus hunting on the edge of the ice. They had done very well, it appeared, at any rate, there was an abundance of food of all kinds. A series of store-chambers had been built side by side with the living rooms, so that by shifting a block of snow, one gained access to the larder, the different kinds of meat being stored in separate compartments; seal meat, caribou meat and salmon, with piles of walrus meat in a shed at one side of the passage. We were at once invited to take as much meat as we liked for our dogs, and while we were feeding them, three pots were set on to boil, that we might have our choice of meats when it came to our turn.

In the course of the afternoon, the master of the house returned. His name was Inugpasugssuk, and he belonged to the Netsilik, as did the rest of the party. It was not long before we became firm friends. This ready frankness and lack of all reserve on the part of the natives was a great asset to me in my work. Where else in the world could one come tumbling into people's houses without ceremony, merely saying that one comes from a country they do not know, and forthwith begin to question them on matters which are generally held sacred—all without the least offence?

We were now but one day's journey from Chesterfield Inlet, and as there seemed to be excellent walrus hunting in the neighborhood, I decided to stay here for a while. Inugpasugssuk was too valuable a find to be dropped all at once. I stayed eight days, in the course of which time we went all through the folklore and legends of the people, without the slightest sign of impatience on his part. After we had done a hundred of the stories, we agreed that he should go with us to Chesterfield, where it would be more convenient to write them down.

We had arrived at Depot Island nearly out of provisions, as our arrangements had been made to include re-stocking at Chesterfield, and we had not reckoned on making any stay here. As it was, however, these good folk, whom we had never seen before, provided us with food for the whole party—five men and twenty-four dogs—throughout our stay, and seemed to regard it quite as a matter of course.

We were all busily occupied meantime. Arnaruluk was making new spring jackets for us, as the hard and heavy winter furs would soon be too hot. Miteq was out walrus hunting all day with the men of the place. At last, when he had got two walrus on his own account, I decided to set out for Chesterfield. Two sledges belonging to the party here helped us to carry our loads of meat, and on the 22nd of April, a calm, warm sunny day, we started for the white men's settlement of which we had heard so much. A couple of hours' journey away, however, we were overtaken by a blizzard which came down on us so suddenly that we lost sight of the others. It was hopeless to go searching about in the dark and the driving snow; we camped, therefore, in three separate parties, none knowing where the others were, and waited for the morning.

Waking up in fine weather after camping hurriedly in a blizzard the night before is always full of surprises. One sees now, from the tangled tracks, how the sledges had been driven this way and that in the darkness and the gale, seeming to pick out the very worst spots. The last part of our journey on the previous night had led us in among a host of little reefs and islets, pressure ridges and fissures, till we brought up finally on a low point of land where a snowdrift offered the site and material for a hut.

Now, all was bathed in the morning sunlight, and the fresh April weather gave a brightness to every hummock and hill; beyond the farthest flat point to the south lay the settlement we had failed to reach. Without waiting for the other sledges, we started off, making our way slowly across the bay, which was deep under snow. Just as we were coming up on to the land again, we found ourselves driving in our own tracks of yesterday, and realized to our surprise that we had been almost in to Chesterfield the night before, but with the wind lashing our faces had turned off a little from the straight and come round in a wide curve.

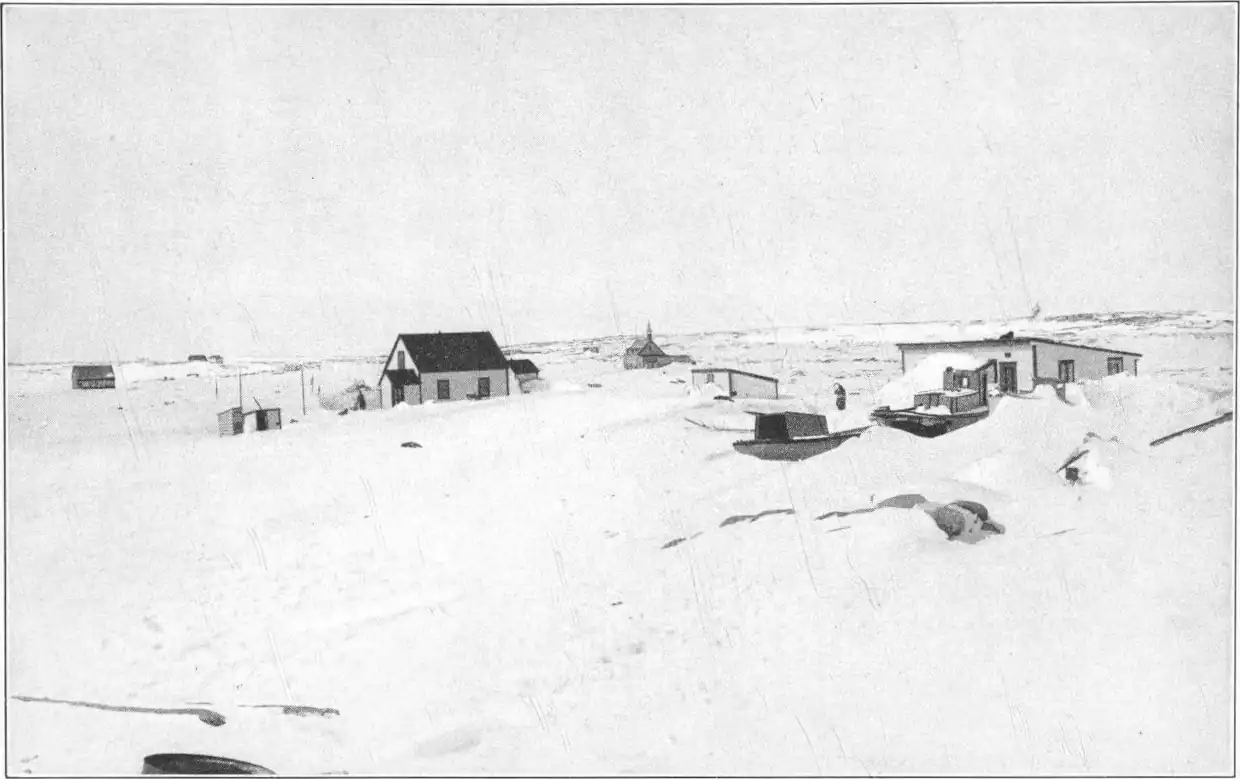

The ascent from the bay was thick with sledge

But the one thing which most of all impressed us as civilized and city-like was a wooden church on the shore of a tiny lake. It had a slender tower rising above the rest of the buildings, and just as we came out on to the lake, the deep, full tones of a bell rang out, as if to greet us. The sound of a church bell made a deep impression on our minds; it was as if we had passed a thousand years in heathen wilds, and now returned to Christendom and peace.

The bell was ringing for service; and there was something affecting in the mere sight of so many people moving, in the old accustomed way of a congregation, slowly, all towards the open doors.

We drove up to the Hudson's Bay Company's offices and were hospitably received by the Station manager, Mr. Phillips. He very kindly invited me to stay with him, but this I declined, as it was essential that I should live as much as possible among the natives in their own free and easy fashion. He then at once placed an empty house at our disposal; we moved in at once, and revelled in the unaccustomed luxury of ample room, coal fires and comfort generally. Anarulunguaq kept house for us, and we decided to live Eskimo fashion on the stores of walrus meat we had brought down with us.

At the Mounted Police barracks I found only a Corporal at home; Sergeant Douglas, who was in charge of the station was away up country investigating a dual murder committed by an Eskimo. The last reports from his patrol stated that travelling was most difficult; deep snow, shortage of food for the dogs, and starving Eskimos all round. This was poor encouragement to us, who were to follow the same route, and farther up country.

The little church whose bell had greeted us so prettily on our arrival belonged to a Roman Catholic Mission, under Father Turquetil and two younger priests, all Jesuits, highly cultured and most interesting to talk to. They opened their house to us with the greatest hospitality, and I spent many an instructive evening in their company. Father Turquetil, a learned man who spoke Eskimo and Latin with equal fluency, had lived in these parts for a generation, and was greatly looked up to by the natives. Converts were not numerous, but the church was full every Sunday.

On the 3rd of May we said goodbye and drove our separate ways.

The mild weather brought with it all the advantages we had been waiting for so long. The snow was moist underfoot, and the stout iron runners made as easy going as the troublesome ice shoeing. We had already decided to follow the narrow gut of Chesterfield Inlet right up to Baker Lake, instead of trying short cuts over hilly and unknown country.

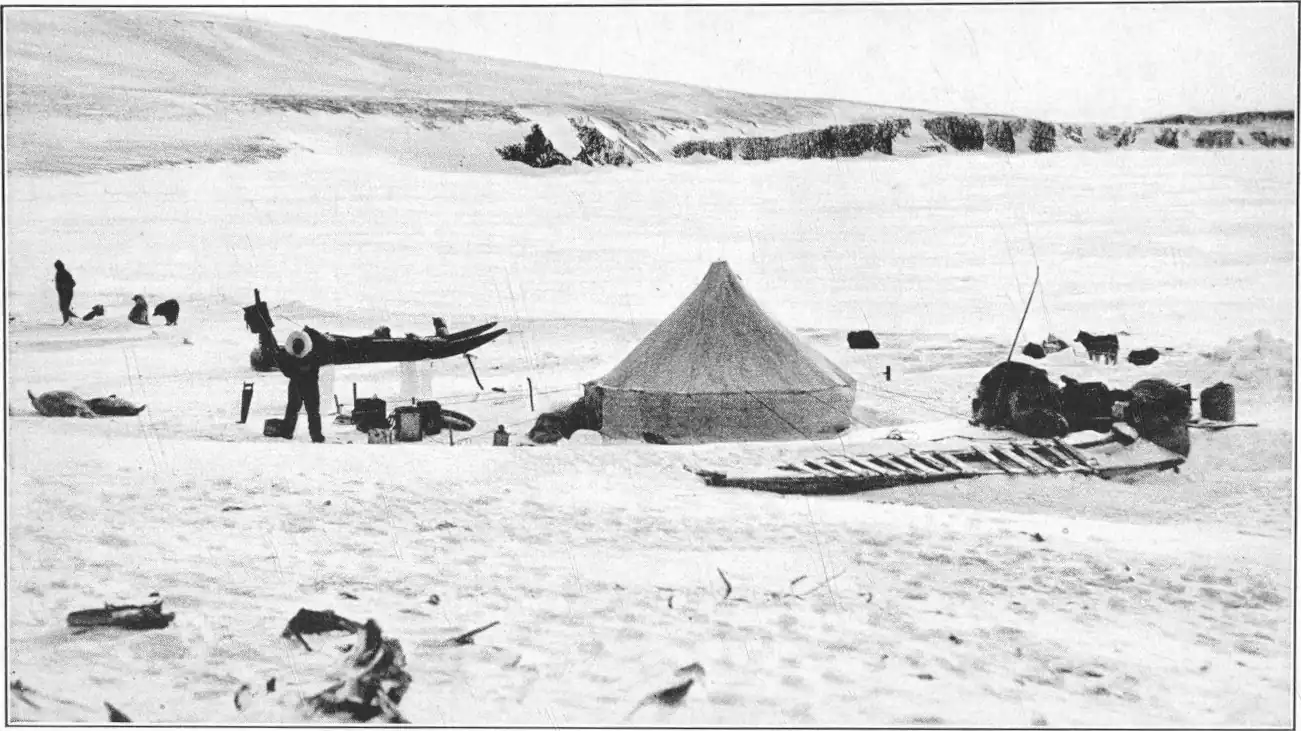

On the morning of the 4th of May we halted to camp; the weather fine and calm, temperature a little over I degree. For the first time during the whole trip we could pitch a tent and call it summer.

All about we found puddles of clean fresh water from the newly melted snow; it was pleasant to kneel and drink from these. Along the slopes, the snow had vanished already, and we could lie down on a luxurious carpet of heather and herbage, eating crowberries and whortleberries by the handful, while chattering ptarmigan tumbled about our ears like snowballs.

But we had now to make the most of the little snow that remained for travelling, and pushed on therefore with all speed, and on the 12th of May we arrived at the little island in Baker Lake where Birket-Smith had been waiting impatiently for our coming. This is the most westerly outpost of the Hudson's Bay Company, and the centre of trade for all the Barren Grounds Eskimos right out to Hikoligjuaq, the Kazan River and the region of the Back or Great Fish River.

We were at once greeted with the good news that there was excellent going on the overland route as long as one travelled by night. And, another point of equal importance to our progress; the caribou were moving up from the south. This was as encouraging as could be wished.

The principal difficulty we had to face was that of getting into touch with our fellow men at all. The only definite information we could gather on this head was, that if we followed the course of the Great Kazan River far enough up, we should meet with two inland tribes. The nearer of the two was called the Harvaqtormiut, or the people of the eddies; farther inland, near Lake Yathkied, or Hikoligjuaq, were the Padlermiut, or Willow-folk. Where the various families were now to be found, no one could say; they followed the moving caribou up in the interior.

We saw no reason to spend any time among the people in the neighborhood of Baker Lake, as these, the Qaernermiut, had for a long time past had dealings with the whalers, and much of their original character had been lost. We therefore transferred our attention without delay to the unknown interior.