Across Arctic America/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V

A People Beyond the Touch

Our way lay through a flat, wild, desolate country, with little to guide the stranger. Although it was the latter part of May, the snow still covered such landmarks as there were, even the rivers were indistinguishable from the plains. All was white save the southern slopes of the hills where the sun had thawed a few bare patches of earth. Hour after hour we travelled on, never seeming to get any farther, and with an uncomfortable feeling all the time that we might be going wrong; as if the sense of direction were at fault. But as a matter of fact, it mattered little which direction we took, for from the day we left the coast we had realized that no information could be gleaned even from one settlement as to the position of another, since the various parties were always on the move, taking up their quarters here or there according to the movements of the game.

On the 18th of May we camped on the top of a ridge of hills, looking out over a wide landscape which, while still under snow, resembles in many ways the inland ice of Greenland, save that moraine takes the place of ice. Isolated masses of rock rising up here and there amid the innumerable lakes and streams, remind one of the Greenland nunataks: mountain tops thrust up above the submerging flood of ice. There are ridges and ranges of hills here, too, as in Greenland, at intervals on the way, until one reaches farther into the interior, when all is merged into one vast level plain.

Standing outside the tent one feels the country like a desert. There is not a sign of life; all game seems to be extinct at this season of the year. No white man ever comes here; unless some crime or other calls for the presence of the ubiquitous Mounted Police. Only a few days back we had heard about Sergeant Douglas' last excursion in quest of a local murderer. He had been up in the coldest season, when the prevalent north-west winds give a degree of cold that few places in the world can surpass. Everywhere he had met with starving natives, moving vainly from place to place in search of food. The caribou had disappeared, the salmon had left the rivers and lakes, and all their hunting failed to yield the barest means of livelihood. The police patrol itself had found the greatest difficulty in getting through to the coast, the dogs being ready to drop with weakness and fatigue; and Douglas himself was known as a clever and experienced traveller.

Toward evening the desolate landscape was tinged with beauty. Light and shade stood out sharply contrasted; but as the sun went down, and all melted and merged into white billows of snow, one was again reminded of the inland ice. Following Chesterfield Inlet, and afterwards Baker Lake, we had not this impression of a vast expanse, but here, with nothing but land to see on every side, we began to realize that these are indeed the Barren Grounds.

Geologically speaking, these are the ruins of what was once a mountainous country, the mountains having been gradually worn away in the course of millions of years. The disintegrating force of alternating heat and cold, action of water, and the rest, have done their work. In the glacial period, a great ice-cap, the Keewatin Glacier, covered all the land. The ice has rounded off all projecting summits, worn away all softer parts, and strewn boulders, great and small, over the whole, until we have now a tract of primitive rock, buried beneath a thick layer of moraine deposit; clay sand and gravel, with only a solitary peak, or its worn remains, jutting up here and there.

On the 19th of May, we passed the first settlement of the Harvaqtormiut, the People of the Eddies. We have decided, however, to use the general term, Caribou Eskimos, for all these inland tribes, the caribou being the principal factor in their life.

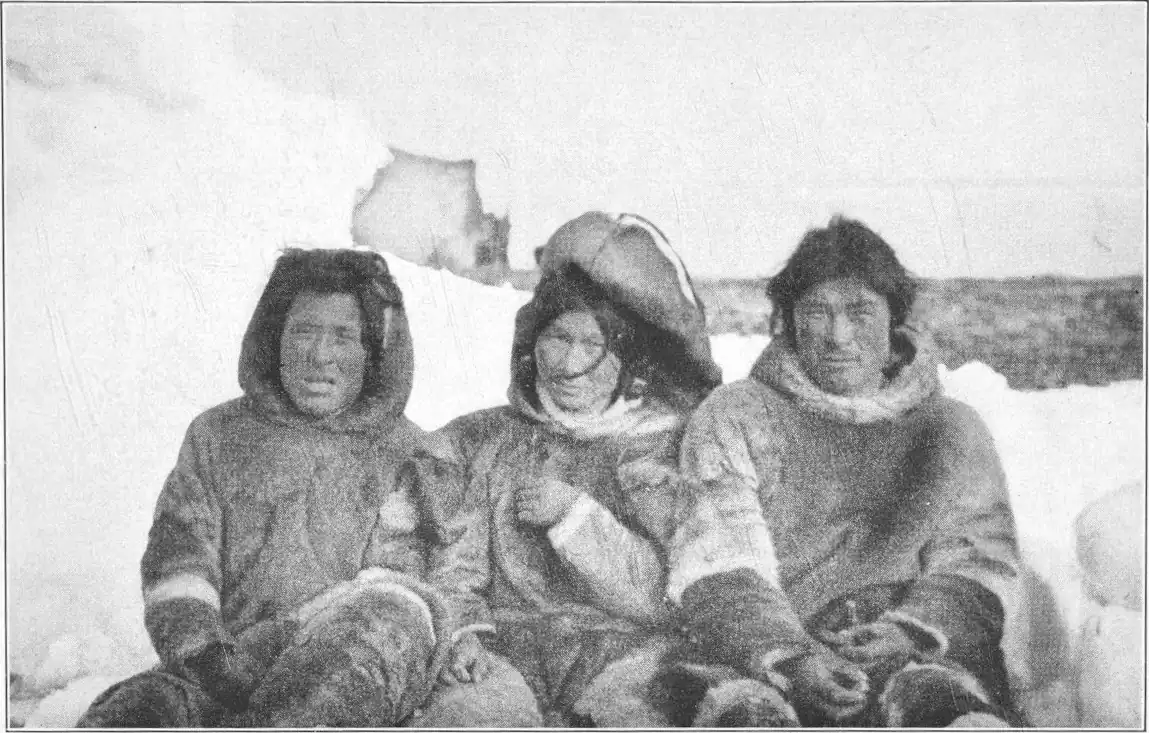

We had made excellent going up to now, the snow firm as a dancing floor under the night's frost. Being, however, four men to one sledge, and that with a heavy load, I preferred to go ahead on ski. We had just topped a rise when to our surprise we discovered a village down by the shore of a tiny lake, with people running in and out of their snow huts in confusion; alarmed, it would seem at our appearance on the scene. When we reached the huts, all the women and children had disappeared, and only two men remained outside, seated on a block of snow, back to back, ready to receive us. Evidently, they were not sure we came as friends. Our whole equipment, with the Greenland sledges and dogs, would be strange to them; they might take us perhaps for a party of the Kitdlinermiut from the shores of the Arctic, or Indians from somewhere up country. Both these they regarded as enemies, the Indians especially, as we learned later on, being looked upon with dread. For centuries past, the Eskimos and the Indians had been at feud, and the atrocities on both sides were not yet forgotten.

While at Baker Lake, I had met a man from the shores of the Arctic, who informed me that there was a special form of greeting used when encountering any of the inland Eskimo. The natives from the coast often went all the way down from the region of the North-west Passage to the timber belt, in quest of wood. And it was their custom on meeting the inland folk, to say at once: Ilorrainik tikitunga, which means: "I come from the right side" i.e., from the proper, friendly, quarter.

I shouted the conventional greeting accordingly, at the top of my voice; and hardly were the words out of my mouth when the two men sprang up with loud cries and came running towards us, while the remainder of the party came tumbling out from their huts.

We now learned that the place was called Tugdliuvartaliik, the Lake of Many Loons. They had had a very severe winter, and numbers of men and dogs alike had died of hunger in various parts. They

Despite the fact that we were but a few days journey from the trading station at Baker Lake, we found that some of the women and children here had never seen white men before. Our cameras were regarded with the greatest astonishment, and a peep through the finder seemed a marvel beyond words. The people here were anxious to trade, and brought along their stores of fox skins, asking in return, however, our most indispensable pots and pans. When we declined to barter these, and explained that we did not care for fox skins, but would rather have old clothes, hunting implements and other curios of ethnographical interest, it was plain to see that we had fallen in their estimation.

We halted for a few hours, made some tea and some pancakes, and on this simple menu stood treat to the whole village. While the impromptu banquet was in progress, in came the two sledges which had been sent out reconnoitring. Long before they reached us we could hear the men shouting: "The caribou are coming; the caribou are coming"; and in a moment the entire assembly was in a turmoil of extravagant rejoicing. Here was the end of winter; the caribou were come, and with them summer and its abundance. And one can imagine what this means to people who have struggled through a whole long winter in the merciless cold of their snow huts, with barely food enough to keep them alive.

On leaving Baker Lake, we had laid our course over land in a curve to the south-east of the Kazan River, having learned that it was inadvisable to follow the lower reaches of the river itself. Now, however, we had to move down to the river in order to get into touch with the natives. One of the young men who had just come in offered to go with us to the next village as a guide, and with his aid, we soon reached the river, which was fairly broad at this point. We crossed over to the spot where the village had been, but found the place deserted; the party had gone off after the caribou. We then sent our guide back at once, and went farther up country, in the hope that we might again manage unaided to get into touch with people here.

The Barren Grounds were now so thick with game that it was hard to make any progress by sledge with dogs used to hunting. Herds of caribou came trotting by, great and small, one after another, numbering from fifteen or twenty-five to fifty, sometimes over two hundred head.

Although it was late in June, we again had winter for a spell. The snow had frozen hard again, caking over everything, and we could make better going now. We followed the winding river through the low-lying country, where the stream itself repeatedly spread out to great width. Here and there the water had begun to eat its way up through the ice, and we had to be very careful in the neighborhood of these eddies. Towards evening we came upon a deserted snow hut, a sure sign that there were people not very far away. But where? There was a confusion of sledge tracks to choose from, but most of them pointed in a direction opposite to that we were inclined to take.

We had left the river now and had reached a lake of such extent that it could hardly be any but Hikoligjuaq itself where the Padlermiut were supposed to have their summer camp. We had followed the eastern bank of the river, as advised, and now at last a man appeared on the summit of a hill, watching us intently. We stopped and waved to him; he answered by stretching out both arms, a sign which said he is a friend. We drove forward accordingly, and soon arrived at his camp.

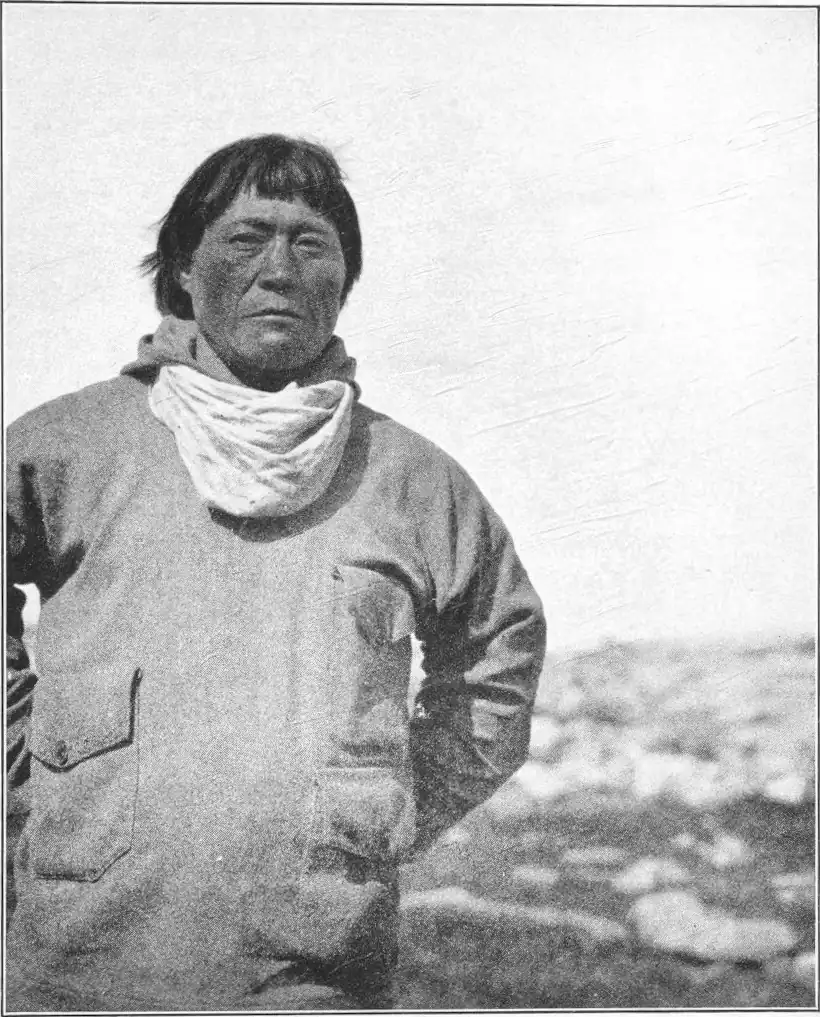

Here at last we found we had reached our goal. We were among the Padlermiut, the Willow-Folk—the head tribe of the Caribou Eskimos.

It was a tiny camp, consisting for the moment of but three tents. Igjugarjuk, the head of the party, unlike the majority of his fellows, greeted us with fearless cordiality, and his jovial smile won our hearts at the outset. I knew a good deal about him, already, from his neighbors on the Kazan River, and had heard the story of how he procured his first wife. It was, to say the least, somewhat drastic, even by Eskimo standards. He had been refused permission to marry her, and therefore went out one day with his brother and lay in wait at the entrance to the lady's hut, and from there shot down her father, mother, brothers and sisters—seven or eight persons in all, until only his chosen herself was left.

I was somewhat surprised then, to find a man of his temper and antecedents introducing himself immediately on our arrival as the accredited representative of law and order. He handed me a document with the seal of the Canadian Government, dated from his camp in April, 1921, when the police had visited there in search of a criminal. Briefly, it set forth that the bearer, one Ed-joa-juk (Igjugarjuk) of She-ko-lig-jou-ak, was by the undersigned, Albert E. Reames, His Majesty's Justice of the Peace in and for the North-west Territory, hereby appointed Special Constable in and for the said territory for the purpose of bringing to justice one Quaugvak, of the Padlermiut, the said Quaugvak being accused of two murders . . .

I read through the document with due solemnity, and handed him in return a bit of old newspaper from a parcel. He took it with great dignity, and studied it with the same attention I had given to his. And from that moment we were friends, with perfect confidence in each other.

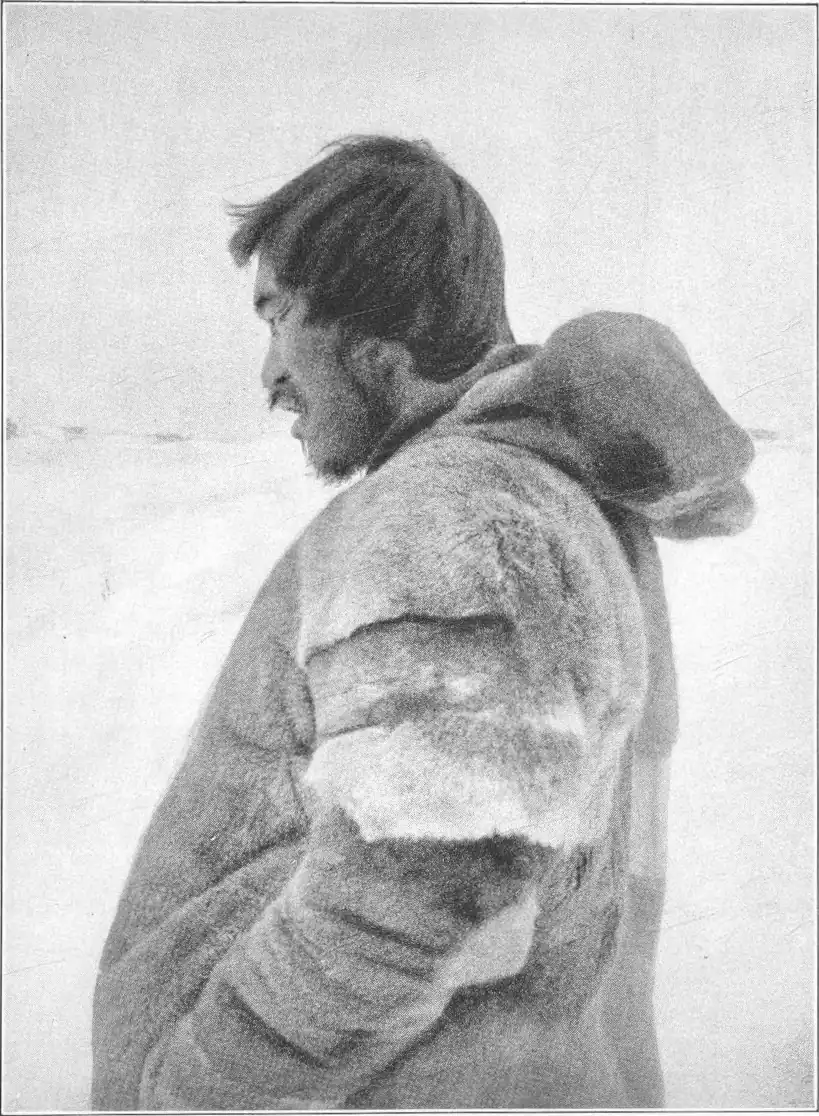

As a matter of fact, Igjujarjuk was no humbug; and when I run over in my mind the many different characters I met with on that long journey from Greenland to Siberia, he takes a prominent place. He was clever, independent, intelligent, and a man of great authority among his fellows.

He invited us at once into one of his tents; and we

To my great relief, the famine we had expected to encounter was already a thing of the past. In front of the tents lay a pile of dead caribou, so many indeed that it was difficult to count them. A month before, the people here had been on the verge of starvation, but now all was changed. Igjugarjuk at once gave orders for an extravagant banquet in our honor, and two large caribou were put on to boil in huge zinc cauldrons.

I had expected to find these people living in quite a primitive state, and in this respect, was disappointed beyond measure. What we did find was the worst kind of tinpot store and canned provision culture; a product of trading expeditions to the distant Hudson's Bay Company's Stations. And when a powerful gramophone struck up, and Caruso's mighty voice rang out from Igjugarjuk's tent, I felt that we had missed our market, as far as the study of these people was concerned. We were about a hundred years too late. Save for their appearance, which was of pronounced Eskimo type, they were more like Indians than Eskimos. Their tents were of the pointed Indian pattern, made of caribou skins with a smoke hole at the top, and in each, on the left hand side, burned the Uvkak, or tent fire. All the women wore colored shawls over their skin dresses, just as the Indian women do; and to my astonishment I found that they wore watches, hung round their necks. These ornaments, however, were divided up among the party, some wearing the case, others going shares in the works.

The only unadulterated Eskimo element we had to work on was the language; and to the satisfaction of both parties, we found that our Greenland tongue was understood immediately, though there was naturally some difference in pronunciation and idiom. Igjugarjuk, who was not beyond flattering a guest, declared that I was the first white man he had ever seen who was also an Eskimo.

The banquet took some time to prepare, and while it was being got ready, we went out to feed our dogs. This gave rise to astonishment not unmixed with horror among our hosts. We had still some of the walrus meat we had brought up from the coast, and this we now brought out. But no such meat had ever been seen on Lake Yathkied, and strange meat was strictly tabu. Here was a difficulty. Igjugarjuk, however, whose travels had made him somewhat a man of the world, met the situation with tact. The young men of his party, he declared, must on no account touch the strange meat, but there would be no harm in our cutting it up ourselves, and feeding our own team with it, as long as we used our own knives.

This little episode showed that our friends were not so hopelessly civilized after all. And when one of the young men, named Pingoaq, came up and asked me whether seal had horns like the caribou, I forgot my disappointment altogether. True, tango melodies were now welling forth from the gramophone, and the meat for our dinner was seething in genuine imported ironmongery; yet these people were plainly different in manners and habit of mind from the ordinary type of Eskimo to whom seal and walrus are the main factor in everyday life. And though I was aware that white men had visited these regions before, I knew also that no one had yet made a thorough study of the people here.

My meditations were interrupted by a shout informing the whole camp that dinner was ready. I have sat down to many a barbaric feast among Eskimos in my time, but I have never seen anything to equal this. Only the elders used knives, the younger members of the party simply tore the meat from the bones in the same voracious fashion which we may imagine to have been the custom of our earliest ancestors. Besides the two caribou, a number of heads had been cooked, and one was served out to each member of our party. The heads were an extra, and we were allowed to keep them till after, to eat in our own tent, on condition that none of the leavings should under any circumstances be touched by women or dogs. The muzzle especially was regarded as sacred meat, which must not be defiled.

Then came dessert; but this was literally more than we could swallow. It consisted of the larvæ of the caribou fly, great fat maggoty things served up raw just as they had been picked out from the skin of the beasts when shot. They lay squirming on a platter like a tin of huge gentles, and gave a nasty little crunch under the teeth, like crushing a black-beetle.

Igjugarjuk, ever watchful, noted my embarrassment and observed kindly: "No one will be offended if you do not understand our food; we all have our different customs." But he added a trifle maliciously: "After all, you have just been eating caribou meat; and what are these but a sort of little eggs nourished on the juices of that meat?"

That same afternoon a whole party of sledges came in from an island out in the lake. It was a remarkable procession to any accustomed to the Eskimos of the coast and their swift teams. Here were six heavily laden sledges, fastened three and three, each section drawn by two dogs only, men and women aiding. The only person allowed to travel as a passenger was an old woman, a mummy-like figure, very aged, and generally looked up to among the Padlermiut on account of her knowledge of tabu and wisdom generally. The fact that she was Igjugarjuk's mother-in-law doubtless counted for something as well.

By the time we had been there one day we began to feel ourselves at our ease among these strange folk. They treated us, apparently, with entire confidence, and endeavored in every way to satisfy our curiosity. In the evening, I ventured to touch on my special subject, and explained to Igjugarjuk, who was famous as an angakoq throughout the whole of the Barren Grounds, that I was most anxious to learn something of their ideas about life, their religion and their folklore. But here I was brought up short. He an

I realized that I was going too fast, and had not yet gained the confidence of my host in full.

It was well on in the forenoon before we turned out on the following morning, and Igjugarjuk at once volunteered to show me the country round.

Just behind the camp was a high range of hills, and from here one had an excellent view of the surroundings. The lake, I found, was enormous, the low-lying coasts vanishing away into the horizon; it looked more like the sea than an inland water. The Indians call it Lake Yathkied, but the Eskimo name is Hikoligjuaq, which means the great water with ice that never melts. The name is justified by the fact that the ice in the middle of the lake rarely if ever thaws away completely.

Igjugarjuk drew for me with surprising readiness a chart of the lake and its shores, noting the names of all the different settlements. A generation or so earlier, there had been some 600 people here; now there were hardly 100. The introduction of firearms has affected the movements of the caribou, and the animals have begun to avoid their old routes and crossings; and when the caribou hunting fails, it means famine to the Eskimo.

The weather was wonderful; the brutal change on change with snow, storm and rain was gone, and everything was at peace. The ice of the lake had melted close to the mouth of the river, and the heavy tumbled winter ice made way in its midst for a smooth sheet of water with a veil of warm mist above. Hosts of swimming birds had found a playground here, and laughed and chattered as new flocks alighted.

On land, one heard all around the little singing sound of melting snow; and the daylight beat so fiercely on the whiteness of the lake that one had to shade one's eyes. Spring had come to the Barren Grounds, and soon earth and flowers would rearise out of the snow.

Small herds of caribou on the move approached within easy distance; but today we were friendly observers only, and felt nothing of the hunter's quickened pulse on seeing them at close range. We had meat enough for the present.

Here again we found the stone barriers, shelters and clumsy figures built to represent a human form, with a lump of peat for a head—relics of the days when caribou hunting was carried on systematically by driving the animals down to the water, where the kayak men were ready to fall upon them with the spear.

With the introduction of firearms, this method of hunting has gone out of fashion, and there will soon be hardly a kayak left in the Barren Grounds. But not many years ago, these inland people were as bold and skilful in the management of a kayak as any of the natives on the coast.

Igjugarjuk and I walked down towards the camp. Far out on the horizon one could see the extreme fringe of the forest, but the sunlight was deceptive, and I could hardly make out for certain whether it were trees or hill. I asked Igjugarjuk, and he answered at once: "Napartut" (the ones that stand up). "Not the true forest where we fetch wood for our long sledges; that is farther still. It is our belief that the trees in a forest are living beings, only that they cannot speak; and for that reason we are loth to spend the night among them. And those who have at some time had to do so, say that at night, one can hear a whispering and groaning among the trees, in a language beyond our understanding."

All the wild creatures were greeting the spring in their mute, humble fashion. We could see hares and lemmings, ermine and marmot snuggling up in the tall grass, with never a thought of feeding, but only enjoying the light and warmth. They were dreaming of an eternal summer, and gave themselves up to the delight of the moment, forgetting all their mortal enemies. Even the wolves, forever lying in wait at other seasons, now resorted to their old den and gave themselves up to domestic bliss. In a fortnight there would be a litter of cubs to look after, and the parents then must take turns to go abroad, for the foxes are quick to scent out anything in the shape of young, even when the sun is at its hottest.

But by the open waters of the lake there was an incessant chattering among the gulls and terns and duck who cannot make out why the loon should always utter such a mournful cry in its happiest moments. There was a blessedness of life and growth here in the spring, when the long-frozen earth at last breathed warm and soft and moist, and plants could stretch their roots in the soil and their branches above. The sand by the river bank gleamed white; showing clearly the footprints of the cranes as they moved. All the birds were talking at once, heedless of what was going on around them, until a flock of wild geese came swooping down, raising a mighty commotion in the water as they alighted. And in face of these, the smaller fry were silent and abashed. But who can paint the sounds of spring? The nature lover will not attempt it, but will be content to breathe its fragrance with rejoicing.

The sun was low on the horizon, the sky and the land all around aglow with flaming color.

"A youth is dead and gone up into the sky," said Igjugarjuk. "And the Great Spirit colors earth and sky with a joyful red to receive his soul."