Across Arctic America/Chapter 6

Chapter VI

Nomad's Life in the Barren Grounds

After our first introduction here, I allowed a few days to pass without pressing my actual errand, spending the time in hunting and bartering a little for ethnographical material. I realized that it would take some time to gain the complete confidence of the natives here.

We lived in our own tent. Among the natives of the coast we had always preferred as far as possible to live in the houses of the natives as we found them, which gave us a better chance of making friends and being regarded as members of the family. In the present instance, however, we kept to our own quarters, not only because we had more time, but also because our hosts here were—to put it mildly—so uncleanly in their habits that it would have been difficult to accommodate ourselves to such conditions.

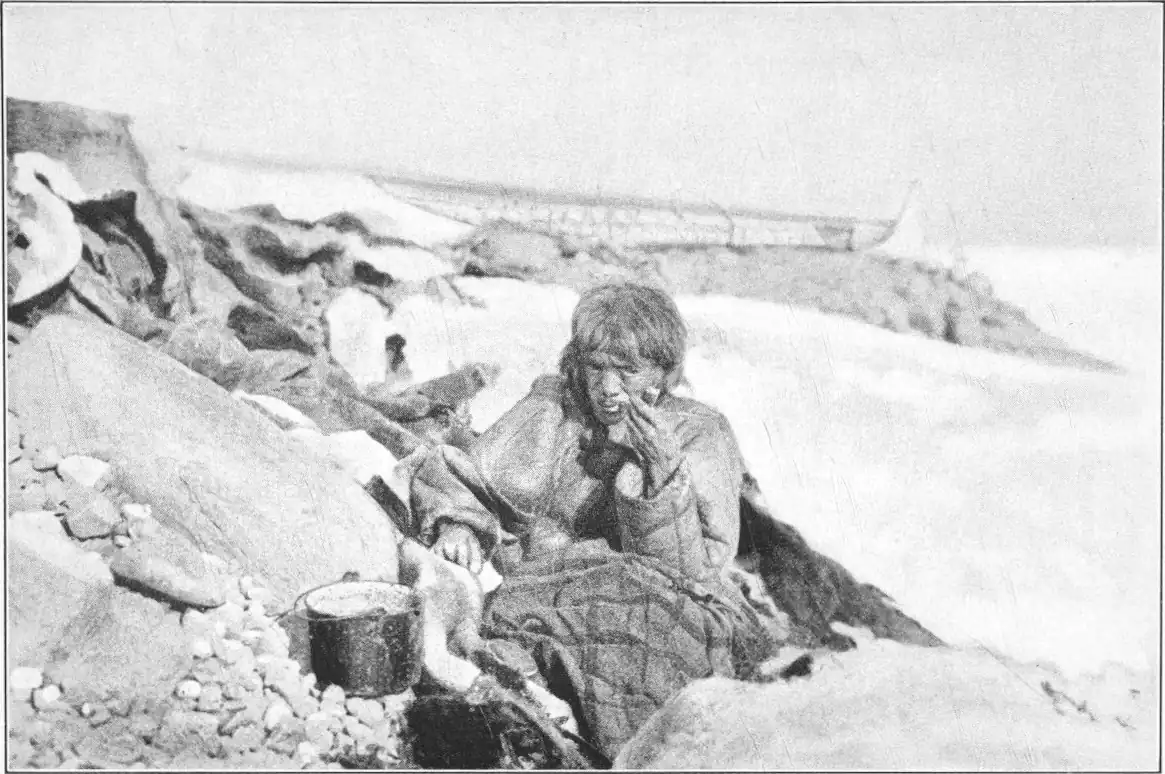

The men were leading a life of idleness just at present, but the women were busy; we were indeed astonished at the amount of work which fell to their share. It was the women who went out gathering fuel, often from a considerable distance, which meant heavy toiling through the swampy soil; they had also to skin and cut up all the caribou brought in, and attend to the fires and the cooking. Their hard life had set its mark upon them; it was not always age, but often simply toil, that had wrinkled their faces; their eyes were often red and rheumy from the smoke of the fires, their hands coarse and filthy, with long, coarse nails. Their womanly charm had been sacrificed on the altar of domestic utility; none the less, they were always happy and contented, with a ready laugh in return for any jest or kindly word.

It suited our purpose well enough that the men were idle, as we had thus more opportunities of gathering the information we sought. In regard to all matters of everyday life they were willing enough to tell us all they knew. The thing which most of all impressed us was their entire independence of the sea. True, they had had some dealings with the natives of the coast districts, a few having made journeys for purposes of trade, but many of the men here had never even seen the sea. And this also accounted for the fact that all sea meat was strictly tabu. Old men were of opinion that their forefathers had always lived inland, their sole means of livelihood being based on caribou, salmon, and birds. Nor was there anything in their material culture to suggest any previous acquaintance with the sea. During the past generation, however, intercourse with neighboring tribes had been somewhat more general, and there had lately been some emigration from the southern end of Hikoligjuag down over the great lakes to the coast at Eskimo Point. The country here was now inhabited by natives from the inland districts. Nevertheless, the natives with whom we

Each hunter had a modern rifle, and there was no difficulty in catching foxes enough to pay for the ammunition required. But they did not seem to realize that the use of firearms was in itself largely responsible for the frequent periods of famine. In the olden days, it is true, hunting was more confined to certain definite seasons; but the ingenious methods and implements of capture gave so rich a yield as to cover also the dead seasons when no game was to be had, as long as the hunting had been fairly good and sufficient meat stored for the winter.

The first essential was to find a site for the village directly on the route followed by the caribou in their migrations, and as these routes differed for spring and autumn, the natives led a somewhat nomadic existence. They always returned, however, to the same spots, as extensive preparations were needed. Hundreds of stone cairns had to be erected covering a range of several kilometres, and the ground had to be chosen so that the caribou could be driven in exactly the direction required. Hunting in the open with bow and arrow gave but a poor return; it was necessary to work up within close range of the animals, which might be a matter of days. And one could never reckon on bringing down more than a couple of head, even where the herds were numerous.

The caribou were shy, and the bow was only effective at short range. This difficulty was met by the following arrangement:

Oblong boulders were set up, or stone cairns built, in two lines, forming an avenue. On top of each stone, or heap of stones, was set a lump of peat or tuft of grass, to look like a head. The avenue was very broad at one end, and so placed that the caribou in flight, coming over a hill, would find themselves between the two lines of figures. Behind were women and children acting as beaters, waving garments and shouting like wolves. The animals seeing themselves, as it appeared, pursued by their enemies from the rear and hemmed in by a line on either side, had no choice but to go straight ahead. As they did so, the space between the lines narrowed in, like an old-fashioned duck decoy, and at the farther end, shelters were built where the hunters lay in wait. The caribou had now to pass within close range of the shelters, and the hunters were able to take toll of them on the way.

The same system of stone figures was employed on the lakes and rivers, at spots where the caribou were accustomed to take to the water. In this case, however, the hunters would lie in wait on the shore, ready to put out in their kayaks. Caribou do not swim very fast, and it was then an easy matter to overtake them and kill them with the spears which were specially fashioned for this form of hunting. Given a broad crossing place and numerous herds, great numbers could be slain in this manner, till the water was choked with the bodies. Some were also taken in winter, in regions where they were to be found at that season, by a system of pitfalls.

Compared with the caribou, all other forms of game were but of minor importance. Fish were caught by spearing or with hook and line; birds, hares, lemmings and marmot taken in snares. The feathered game was mostly hunted in the autumn, when the birds are moulting and cannot rise easily. They are then pursued on the water in kayaks, and killed with small harpoons.

Unfortunately, the kayak is now being superseded altogether by the gun, and it will not be long before kayaks are a thing of the past. The gun has immediate advantages, but it is doubtful whether it pays better in the long run. Naturally, it is tempting to employ a weapon which does away with the need for elaborate preparation of dummies and shelters, and there is little difficulty on thinning out the herds with a long-range rifle. But it should be borne in mind that arrow and spear did their work silently, and without scaring the rest, so that the caribou continued for centuries to follow the same routes from the forests to the Barren Grounds and back again. Now, since the introduction of firearms, a change seems to have taken place in this respect; the animals tend more and more to avoid the native villages, and famine has frequently resulted. In some districts, during the last few years, the inhabitants have been completely exterminated by starvation.

Another difficulty which the Caribou Eskimos have to reckon with is the fact that the moving of the caribou in summer and autumn comes just at those seasons when travelling is most difficult. The great stretches of tundra are a pathless waste, and the rivers are available only as their course lies, often tending in the wrong direction for pursuit of the caribou. It is not until late in the autumn, when the rivers and lakes are frozen over, and the country is covered with snow, that they are able to cover any distance; but under these conditions, they are splendid travellers, skilful and untiring. In the days before the trading stations were established at Baker Lake and Eskimo Point, they would go south as far as Fort Churchill, and west to the region of Schultz Lake and Aberdeen Lake. Here they had their meeting place at the famous Akilineq, a ridge of hills south of the great lakes in the neighborhood of the Thelon River. Here they procured timber for sledges, kayaks and tent poles, from Lake Tivsalik, where great tree trunks, brought down by the river from far up country, were washed ashore. One can imagine the patience required in those old days for any kind of wood work, when the only tools available were odd scraps of iron. Now, of course, the saw is generally in use; and sawn timber cut to standard sizes can be obtained at the trading stations.

Akilineq was the meeting place for the natives from Baker Lake and Kazan River, who encountered here the tribes from regions so far distant as the North-west Passage, likewise coming up in search of timber. There was naturally a good deal of trading between the different tribes thus brought into contact. The inland folk traded white men's goods

There were also forests by the shores of these lakes, but as the trees were regarded as living beings, they were rarely visited. There was a widely current tradition, of ancient date, that the tree-folk would not suffer any human being among them for more than ten nights.

It says much for the skill and endurance of the Eskimos as travellers that these long journeys were made with very small teams, rarely more than two, and never more than five dogs, owing to the difficulty of procuring food for the animals. Both men and women, however, were hardy walkers, and would cheerfully harness themselves to the sledge and haul as well as any dog. Despite their small teams, these natives here use, curiously enough the longest sledges known to exist anywhere; ten metres in length by only 43 centimetres across are by no means unusual measurements. Thanks to the ice shoeing, however, they were easy to haul, and their length made for steadiness and buoyancy in soft loose snow.

We were anxious to ascertain whether any stone houses existed up inland, such as we had found all along the coast; our informants here, however, were positive that none such had ever been seen. Houses of this type would also be inconsistent with their mode of life, which involved a constant moving from place to place at certain seasons of the year.

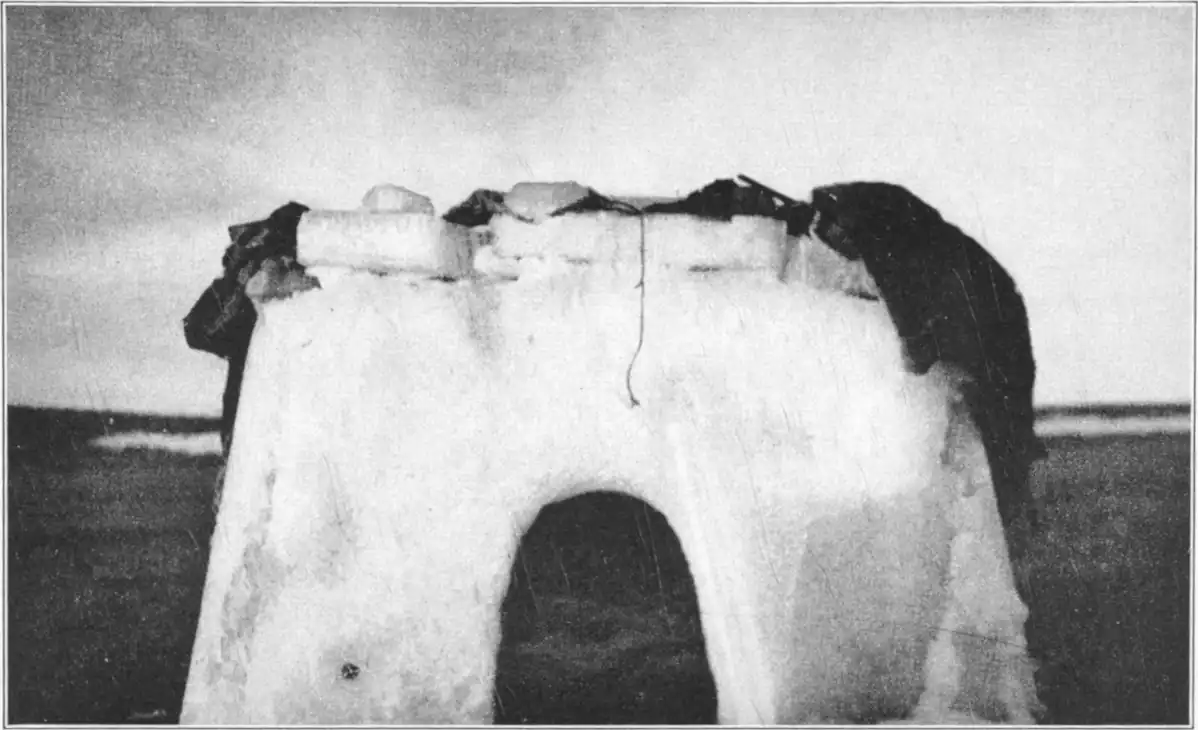

The only form of winter dwelling known to the inland Eskimo is the snow hut; but having no oil or blubber, they are unable to heat them, though the thermometer in the cold season may often fall below minus 50°. During the long, dark evenings, their only light is a sort of primitive tallow dip, made of moss and caribou fat. So hardy, however, are these people that they declare they never feel cold indoors, however severe the weather may be; and their houses are also protected against the blizzards by being simply smothered in snow, till they are hardly distinguishable from the drift in which they are built.

Just outside the living room proper, and connected with it by a passage is the so-called iga, or kitchen, built straight up with steep walls, to prevent the snow from melting. Here the food is cooked, when any fuel is available; this, however, is by no means an everyday occurrence when the whole country lies deep in snow. For days in succession they may have to make do with frozen meat, and not even a mouthful of hot soup to help it down.

Water supply is ensured by building the snow hut close to the shore of a lake, and a hole is kept open in the ice all through the winter, a small snow hut being built above the opening to keep it from freezing. Like all other Eskimos living exclusively on meat, these inland folk drink enormous quantities of water.

The only serious difficulty they have to contend with is that they have no means of getting their footwear dried after a long day's hunting. If they have skins enough, the wet things are thrown away and replaced by new ones; failing this, the old wet things have to be dried at night by laying them next to the body.

In May, the snow huts begin to melt, and tents are then called into requisition, often of great size and magnificence, made on the Indian pattern, with smoke hole at the top, and of caribou skin throughout. In front of the house-wife's seat is the fireplace, and all meals are cooked here, inside the tent, the weather as a rule being very windy. One might imagine that the moving into tents meant a period of comfort and ease; this, however, is by no means the case. The cooking indoors precludes the use of a curtain at the entrance, and one has thus either to sit in a roaring draught, or in a smother of smoke from the fireplace. Often we had to jump up half stifled and hurry outside to breathe, though the rest of the inmates appeared to find no discomfort from the atmosphere.

This, roughly, is the ordinary everyday life of the inland Eskimos, probably the hardiest people in the world. Their country is such as to offer but a bare existence under the hardest possible conditions, and yet they think it the best that could be found. What most impressed us was the constant change from one to another extreme; either they are on the verge of starvation, or wallowing in a luxury of abundance which renders them oblivious of hard times past, and heedless of those that await them in the next winter's dark.

Igjugarjuk, who had so vehemently asserted that he was no magician, and knew nothing of the past history of his people, soon changed over when he found that he could trust me, and realized that I was earnestly interested in such matters. And in the end, I learned from him a great deal about aspects of Eskimo culture which were quite new to me.

I found it impossible to get a clear and coherent account of their religious beliefs; as soon as one began to ask about matters outside the sphere of tangible reality, the views expressed were so contradictory that one could make nothing of them together. Nothing definite was known, nor did it seem to matter that the wise men of the tribe held different views one from another; the one thing certain was, that all study of such matters was attended with the greatest difficulty, and much remained beyond our knowledge. The general view of life after death is best shown in the following story, which was told to me by Kivkarjuk:

"Heaven is a great country with many holes in. These holes we call the stars. Many people live there, and whenever they upset anything, it falls down through the stars in the form of rain or snow. Up in the land of heaven live the souls of dead men and beasts, under the Lord of Heaven, Tapasum Inua.

"The souls of men and beasts are brought down to earth by the moon. This is done when the moon is not to be seen in the sky; it is then on its way to earth, bringing souls. After death, we do not always remain as we were during life; the souls of men, for instance, may turn into all kinds of animals. Pinga looks after the souls of animals, and does not like to see too many of them killed. Nothing is lost; and blood and entrails must be covered up after a caribou has been killed.

"So we see that life is endless; only we do not know in what form we shall reappear after death."

The easiest way to learn, of course, was to inquire of an angakoq, and in the course of my long conversations with Igjugarjuk I learned many interesting things. His theories, however, were so simple and straightforward that they sound strikingly modern; his whole view of life may be summed up in his own words as follows: "All true wisdom is only to be learned far from the dwellings of men, out in the great solitudes; and is only to be attained through suffering. Privation and suffering are the only things that can open the mind of man to those things which are hidden from others."

A man does not become an angakoq because he wishes it himself, but because certain mysterious powers in the universe convey to him the impression that he has been chosen, and this takes place as a revelation in a dream.

This mysterious force which plays so great a part in men's fate, is called Sila, and is very difficult to define, or even to translate. The word has three meanings: the universe; the weather, and finally, a mixture of common sense, intelligence and wisdom. In the religious sense, Sila is used to denote a power which can be invoked and applied by mankind; a power personified in Silap Inua, the Lord of Power, or literally, the one possessing power. Often also, the term Pinga is used, this being a spirit in the form of a woman, which is understood to dwell somewhere in space, and only manifests itself when specially needed. There is no definite idea as to her being the creator of mankind, or the origin of animals used for food; all fear her, however, as a stern mistress of the household, keeping watch on all the doings of men, especially as regards their dealings with the animals killed.

She is omnipresent, interfering as occasion may require. One of her principal commandments appears to be that daily food should be treated with respect, care being taken that nothing is wasted. There are certain ceremonies, for instance, to be observed on the killing of a caribou, as mentioned in the story just quoted.

All the rules of tabu are connected with Sila, and designed to maintain a balance of amicable relations with this power. The obligations imposed by Sila are not particularly burdensome, and perhaps for that very reason trespass is severely punished; as for instance by bad weather, dearth of game, sickness, and the like; in a word, all that is most to be feared.

The angakoq serves as interpreter between Sila and mankind. Sila's leading qualities are those of healing in sickness or guarding against the illwill of others. When a sick person desires to be cured, he must give away all his possessions, and is then carried out and laid on the earth far from any dwelling; for whoever would invoke the Great Spirit must have no possessions save his breath.

Igjugarjuk himself, when a young man, was constantly visited by dreams which he could not understand. Strange unknown beings came and spoke to him, and when he awoke, he saw all the visions of his dream so distinctly that he could tell his fellows all about them. Soon it became evident to

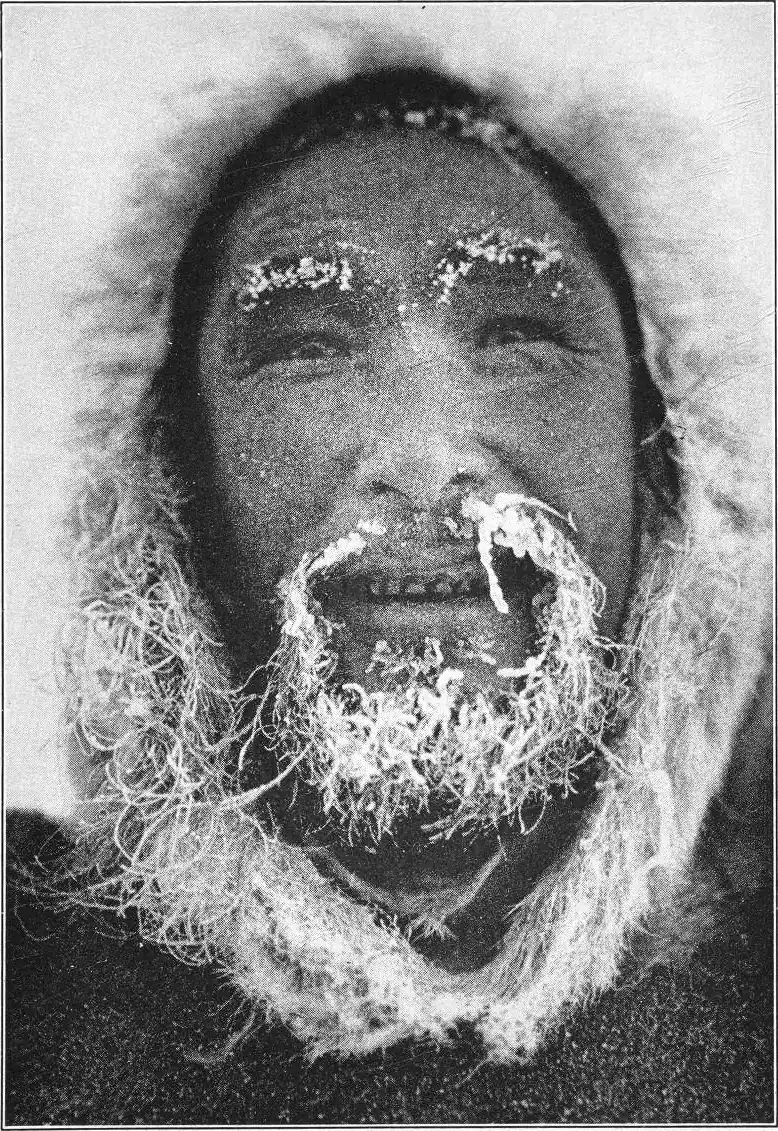

After five days had elapsed, the instructor brought him a drink of lukewarm water, and with similar exhortations, left him as before. He fasted now for fifteen days, when he was given another drink of water and a very small piece of meat, which had to last him a further ten days. At the end of this period, his instructor came for him and fetched him home. Igjugarjuk declared that the strain of those thirty days of cold and fasting was so severe that he "sometimes died a little." During all that time he thought only of the Great Spirit, and endeavored to keep his mind free from all memory of human beings and everyday things. Towards the end of the thirty days there came to him a helping spirit in the shape of a woman. She came while he was asleep, and seemed to hover in the air above him. After that he dreamed no more of her, but she became his helping spirit. For five months following this period of trial, he was kept on the strictest diet, and required to abstain from all intercourse with women. The fasting was then repeated; for such fasts at frequent intervals are the best means of attaining to knowledge of hidden things. As a matter of fact, there is no limit to the period of study; it depends on how much one is willing to suffer and anxious to learn.

Every wizard has a belt, which often plays a great part in his invocations of the spirits. I was fortunate enough to acquire one of these belts from a woman who was herself a witch doctor, named Kinalik. It consisted of an ordinary strap of hide on which were hung or strung the following items: a splinter from the stock of a gun worn in recognition of the fact that her initiation had taken place by means of visions of death; a piece of sinew thread, which had formerly been used to fasten tent poles with, and had on some occasion or other been used for a magic demonstration; a piece of ribbon from a packet of tobacco; a piece of an old cap formerly belonging to her brother the brother was now dead, and was one of her helping spirits-a piece of white caribou skin, some plaited withies, a model of a canoe, a caribou's tooth, a mitten and a scrap of sealskin. All these things possessed magnetic power, by virtue of their having been given to her by persons who wished her well. Any gift conveys strength. It need not be great or costly in itself; the intrinsic value of the object is nothing, it is the thought which goes with it that gives strength.

Kinalik was still quite a young woman, very intelligent, kind-hearted, clean and good-looking, and spoke frankly, without reserve. Igjugarjuk was her brother-in-law, and had himself been her instructor in magic. Her own initiation had been severe; she was hung up to some tent poles planted in the snow and left there for five days. It was midwinter, with intense cold and frequent blizzards, but she did not feel the cold, for the spirit protected her. When the five days were at an end, she was taken down and carried into the house, and Igjugarjuk was invited to shoot her, in order that she might attain to intimacy with the supernatural by visions of death. The gun was to be loaded with real powder, but a stone was to be used instead of the leaden bullet, in order that she might still retain connection with earth. Igjugarjuk, in the presence of the assembled villagers, fired the shot, and Kinalik fell to the ground unconscious. On the following morning, just as Igjugarjuk was about to bring her to life again, she awakened from the swoon unaided. Igjugarjuk asserted that he had shot her through the heart, and that the stone had afterwards been removed and was in the possession of her old mother.

Another of the villagers, a young man named Aggjartoq, had also been initiated into the mysteries of the occult with Igjugarjuk as his teacher; and in his case, a third form of ordeal had been employed; to wit, that of drowning. He was lashed to a long pole and carried out on to a lake, a hole was cut in the ice, and the pole with its living burden thrust down through the hole, in such a fashion that Aggjartoq actually stood on the bottom of the lake with his head under water. He was left in this position for five days and when at last they hauled him up again, his clothes showed no sign of having been in the water at all and he himself had become a great wizard, having overcome death.

These inland Eskimos are very little concerned about the idea of death; they believe that all men are born again, the soul passing on continually from one form of life to another. Good men return to earth as men, but evildoers are re-born as beasts, and in this way the earth is replenished, for no life once given can ever be lost or destroyed.