Across Arctic America/Chapter 7

Chapter VII

With No Editors to Spoil

We very soon realized that the culture of these Caribou Eskimos was of inland origin. It was the most primitive we had encountered during the whole of the expedition, and all the facts tended to show that we were here well on the way to a solution of one of our most important problems.

Their religion, for instance, was of a pronounced inland type, differing essentially from that of the coast peoples, and in respect of tabu especially unlike that of the sea and shore. The ceremonies attending birth and death in particular were far simpler than those in use among the coast Eskimos. Plainly, the people who first found their way to the sea had seen in it, and in the mode of life which it involved, new and mysterious elements which had given rise to their complicated mythology and ceremonial.

The fact that the sea was new to them was further confirmed by the entire absence of any implements, whether among those in use or others now obsolete, such as would be used by dwellers on the coast.

Nevertheless, we soon found that they had many traditions in common with the Greenland Eskimos; indeed, a number of their folk-tales and legends are altogether identical with Greenland stories.

Out of fifty-two stories which I wrote down among the Padlermiut at Hikoligjuaq, no fewer than thirty were identical with ones I had already heard in Greenland, and this despite the fact that for thousands of years past, no intercourse had taken place between the two groups of people.

An unquestionable connection exists between the Greenlanders and their Canadian kinsfolk in the matter of story and legend. These stories moreover show that the poor Eskimo can at times find room for thought of things beyond the mere material needs of the day; many of them show a forceful simplicity, a touch of epic strength, and a poetic sense, which command our admiration.

Here are several of the shorter ones:

The Owl that Wooed a Snow Bunting

There was once a little snow bunting; it sat on a tuft and wept because its husband was dead. Then came a big fat Owl and sang:

The little bird answered:

Told by Kivkarjuk, of Hikoligjuaq.

(Known throughout the whole of Greenland.)

How the White Men and the Indians Came

There was once a maiden who refused all men who wished to marry her. At last her father was so annoyed at this that he rowed off with her and his dog to an island out in the lake of Haningajoq, not far from Hikoligjuaq, and left her there with the dog. Then the dog took her to wife, and she gave birth to many whelps. And her father brought meat to the island, that they might not die of hunger. One day when they were grown up, their mother said to them: "Next time your grandfather comes out to the island, swim out to meet him, and upset his kayak."

The dogs did so and the girl's father was drowned. Thus she took vengeance upon her father for having married her to a dog. But now that he was dead, there was no one to bring the dogs meat, so the girl cut the soles out of her kamiks, and placed them in the water, and worked magic over them. Then she set some of the dogs on one sole, and said: "Go out into the world and become skilful in all manner of work!"

And the dogs drifted out away from the island and when they had gone a little way, the sole turned into a ship, and they sailed away to the white men's country and became white men. And from them, it is said, all white men are descended.

But the rest of the dogs were set on the other sole, and as it floated away, the girl said: "Take vengeance for all the wrong your grandfather did to me, and show yourselves henceforward thirsty for blood as often as you meet one of the Inuit."

And the dogs sailed away to a strange land, and went ashore there and became the Itqigdlit. From these are descended all those Indians whom our forefathers dreaded, for they slew the Inuit wherever they could find them. And this they continued to do until their brothers, the white men from the island of Anarnigtoq, took land in their country and taught them gentler ways.

Told by Igjugarjuk.

(This story is known in Greenland.)

The Raven and the Loon

In the olden days, all birds were white. And then one day the raven and the loon fell to drawing patterns on each others feathers. The raven began, and when it had finished, the loon was so displeased with the pattern that it spat all over the raven and made it black all over. And since that day all ravens have been black. But the raven was so angry that it fell upon the loon and beat it so about the legs that it could hardly walk. And that is why the loon is such an awkward creature on land.

(There is a Greenland version of this.)

Thunder and Lightning

In the olden days, nobody ever stole anything. But then one day when a great song festival was being held, two children were left alone in a house. Here they found a caribou skin with the hair off, and a firestone, and desired to have these things for their own. But hardly had they taken them when a great fear came upon them.

"What shall we do," cried one, "to get away from people?"

"Let us turn ourselves into caribou," answered the other."

"No; for then they will catch us; let us turn into wolves."

"No; for then they will kill us. Let us turn into foxes."

And so they went on, naming all the animals there were, but always fearing that men should kill them. Then at last one said: Let us be thunder and lightning. For then men could not reach them. And so it came about; they went up into the sky and became thunder and lightning. And now when we hear the thunder it is one of them rattling the dry skin, and when we see the lightning it is the other one striking sparks from the stone.

Told by Arnarqik, of Nahigtartorvik, Kazan River.

(Also known in Greenland.)

The Owl and the Marmot

There was once an owl who went out hunting, and seeing a marmot outside its house, it flew towards it and sitting down in front of the entrance, sang:

"I have barred the way of a land beast to its home. Come and fetch it, and bring two sledges."

But the marmot answered: "O mighty owl, spread your legs a little wider apart, and show me that powerful chest."

And the owl hearing this was proud of its broad chest, and spread its legs wider apart.

Then the marmot cried: "Wider, wider still."

And the owl feeling even prouder than before spread its legs a little wider still, and stretched its chest as far as it could.

But then the marmot slipped between its legs and and ran off into its hole.

Told by Kivkarjuk.

I was told that there should be a larger settlement on the southern shore of Hikoligjuaq, and I determined to cross and pay a visit to the natives there. On the day before our departure, a grand song festival was arranged, to be held in Igjugarjuk's tent. In the afternoon the guests arrived, as many as the tent would hold. The singer stood in the middle with closed eyes, accompanying his song with a swaying movement of the hips, while the women, seated in a group on the bench, joined in the chorus every now and then, their voices contrasting pleasantly with the deeper tones of the men.

Here are the words of some of the songs:

Igjugarjuk's Song

Avane's Song

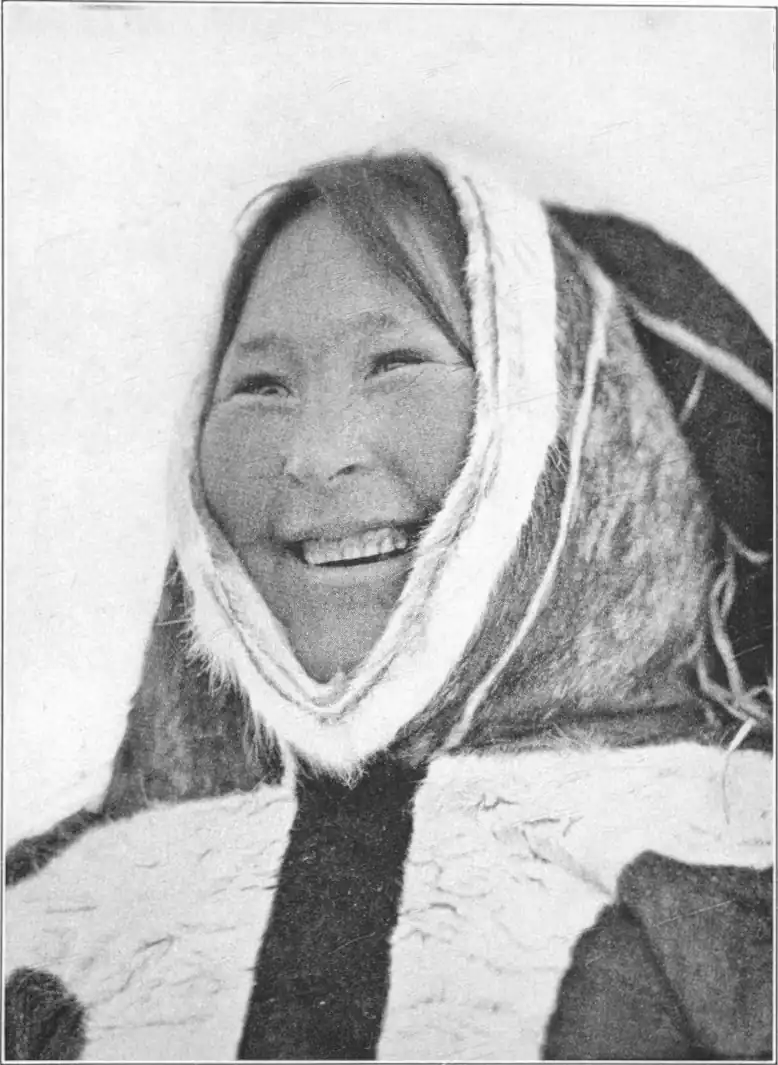

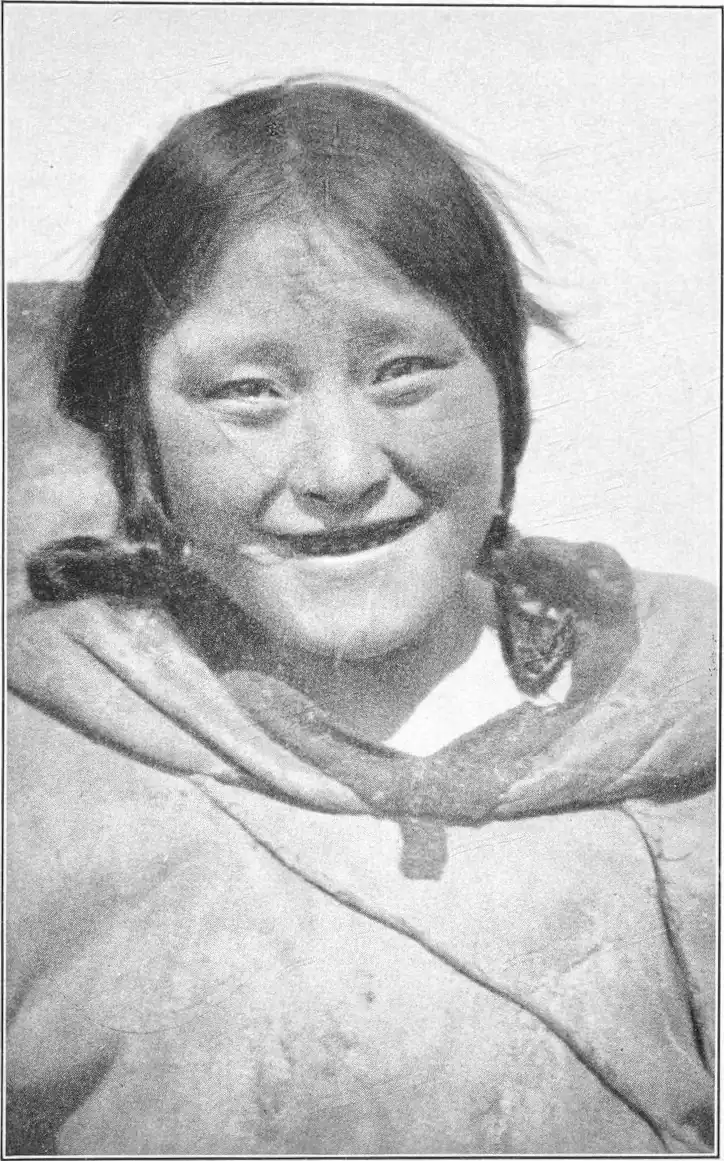

Women do not as a rule sing their own songs. No woman is expected to sing unless expressly invited by an angakoq. As a rule, they sing songs made by the men. Should it happen, however, that a woman feels a spirit impelling her to sing, she may step forth from the chorus and follow her own inspiration. Among the women here, only two were thus favored by the spirits; one was Igjugarjuk's first wife, Kivkarjuk, now dethroned, and the other Akjartoq, the mother of Kinalik.

Kivkarjuk's Song

Akjartoq's Song

I give here Utahania's impeachment of one Kanaijuaq who had quarrelled with his wife and attempted to desert her, leaving her to her fate out in the wilds; the woman, however, had proved not only able to stand up for herself in a rough-and-tumble, but left her husband of her own accord and went to shift for herself, taking her son with her.

Kanaijuaq retorted with a song accusing Utahania of improper behavior at home; his hard words however, seemed to make no difference to their friendship. Far more serious was the effect of malicious words in the case of Utahania's foster-son who was once upbraided by his foster-father as follows:

"I wish you were dead! You are not worth the food you eat." And the young man took the words so deeply to heart that he declared he would never eat again. To make his sufferings as brief as possible, he lay down the same night stark naked on the bare snow, and was frozen to death.

Halfway through the festival it was announced that Kinalik, the woman angakoq, would invoke her helping spirits and clear the way of all dangers ahead. Sila was to be called in to aid one who could not help himself. All the singing now ceased, and Kinalik stood forth alone with her eyes tightly closed. She uttered no incantation, but stood trembling all over, and her face twitched from time to time as if in pain. This was her way of "looking inward," and penetrating the veil of the future; the great thing was to concentrate all one's force intently on the one idea, of calling forth good for those about to set out on their journey.

Igjugarjuk, who never let slip an opportunity of exalting his own tribe at the expense of the "salt water Eskimo," informed me at this juncture that their angakoqs never danced about doing tricks, nor did they have recourse to particular forms of speech; the one essential was truth and earnestness—all the rest was mere trickwork designed to impress the vulgar.

When Kinalik had reached the utmost limit of her concentration, I was requested to go outside the tent and stand on a spot where there were no footmarks, remaining there until I was called in. Here, on the untrodden snow, I was to present myself before Sila, standing silent and humble, and desiring sky and air and all the forces of nature to look upon me and show me goodwill.

It was a peculiar form of worship or devotion, which I now encountered for the first time; it was the first time, also, that I had seen Sila represented as a benign power.

After I had stood thus for a time, I was called in again. Kinalik had now resumed her natural expression, and was beaming all over. She assured me that the Great Spirit had heard her prayer, and that all dangers should be removed from our path; also, that we should have success in our hunting whenever we needed meat.

This prophecy was greeted with applause and general satisfaction; it was plain to see that these good folk, in their simple, innocent fashion, gave us their blessing and had done all they could to render it effective. There was no doubting the sincerity of their goodwill.

On the following night we were racing at full speed over the wintry surface of Lake Hikoligjuaq. The firm ice was spread with a thin layer of soft, moist snow, acting as a soft carpet to the dogs' paws, and the long rest in complete idleness with plenty of fresh caribou meat had given them a degree of vitality that made it a pleasure to be out once more. We had two lads with us as guides, who had borrowed Igjugarjuk's dogs, but it was not long before they were hopelessly out-distanced, and we had to content ourselves with a guess at our direction.

Early in the morning, before the sun was fairly warm, we reached the southern shore of the lake and camped in a pleasant little valley, fastening the dogs in a thicket of young willow that stood bursting in bud to greet the spring.

In the course of the day we went out to reconnoitre. And it was not long before we came upon a solitary caribou hunter observing us from a little hill. He was just taking to flight when the two lads from the last village, who had now come up, recognized him and called him by name, when he walked up smiling to meet them. He informed us that there was a village of five tents a couple of hours' journey farther inland, and that we could reach the place without difficulty, although the ground was bare. We tried to persuade him to come back with us to the camp, but he preferred to go on ahead and tell his comrades of the strange meeting. And before we had gone far, the whole party came down and overtook us, they had been too impatient to wait for our arrival. It was hard work for the dogs to get the sledge over the numerous hills, and even the level ground was difficult going, sodden as it was with water and broken by tussocks and pools. There were plenty of willing hands, however, and we made our way, albeit slowly, with a great deal of merriment. Miteq and I had to face an endless rain of questions. These inland folk look upon the sea as something wonderful and mysterious, far beyond their ken; and when we explained that we had had to cross many seas in coming from our own land to theirs, they regarded our coming in itself as something of a marvel. And we agreed with them in their surprise at our being able to understand one another's speech.

Suddenly speech and laughter died away; the dogs pricked up their ears, and a strange silence fell upon all. There, full in our way, lay the body of a woman prone on the ground. We stood for a moment at a loss. Then the men went forward, while we held back our dogs. The figure still lay motionless. A loud wailing came from the party ahead, and Miteq and I stood vaguely horrified, not knowing what it meant. Then one of the men came back and explained that we had found the corpse of a woman who had been lost in a blizzard the winter before—and he pointed to one of those bending over her; that was her husband.

It had been a hard winter, and just when the cold was most severe, six of those in the village had died of hunger. A man named Atangagjuaq then determined to set out for a neighboring village in search of aid, and his wife, fearing lest, weak as he was, he might be unable to complete the journey, had followed after him. She herself, however, had been lost in the snow before coming up with him. They had searched for her that winter, and in the following spring, but without result; and now here she lay, discovered by the merest accident right athwart our course.

I walked forward to view the body of this woman who had lost her life in a vain attempt to help her husband. There was nothing repulsive in the sight; she just lay there, with limbs extended, and an expression of unspeakable weariness on her face. It was plain to see that she had walked on and on, struggling against the blizzard till she could go no farther, and sank exhausted, while the snow swiftly covered her, leaving no trace.

The body was left lying as it was; no one touched it. We drove on, and in an hour's time reached the Eskimo camp.

These people are quick to change from one extreme of feeling to another. We had not gone far on our way before the dead woman, to all seeming, was forgotten, and the merriment that had met with so sudden a check broke out afresh. As soon as we had put up our tent, the men got hold of our ski, and went off to try them in a good deep snowdrift that still lay in a gap. They had never seen ski before, and great shouts of laughter greeted the first attempts of those venturesome enough to try them. One of the gayest of the party was Atangagjuaq, who but a few minutes earlier had stood weeping beside the body of his wife.

By the 21st of June, we were once more on the ice of Lake Hikoligjuaq, and on the morning of the 22nd, just at sunrise, we reached the spot where the others of our party were encamped. That sunrise was, I think, the most remarkable I have ever seen. To the north, on the horizon, was a dense white mass of cloud, like a reflection from the lake itself, but with a narrow belt of delicate green below. The country round was outlined in masses of black. Then suddenly there was a glow of fire, a tongue of flame broke through the pale green below the cloud, lighting up all the sky; light, fragile veils of rosy cloud-stuff floated by overhead, and the ice below was tinged with the palest mauve. The contours of shore and hill stood out now darker than before, while flowers of fire appeared on the horizon like fairy-lamps lit one after another, gradually merging into one great conflagration. Then up came the sun itself, and all the varied colors were lost in one stark red glow reflected in our faces as we looked.

It was like driving into a burning city; and we remained spellbound until the barking of dogs and shouts of welcome from our companions brought us back to reality and busy freshness of a new day. . . .