Across Arctic America/Chapter 8

Chapter VIII

Between Two Winters

Igjugarjuk had for some time past been talking of making a trip down to Baker Lake, and was now getting ready for the journey. Then one day a canoe came up from the south, in charge of a young man, Equmeq, by name. It was decided that Birket-Smith and Bangsted, with the greater part of our ethnographical collections, should start with this party for Baker Lake, Igjugarjuk taking the rest, and Miteq and I going by sledge—a plan which caused much head-shaking among the natives, who regarded sledging as dangerous or impossible at this season.

Certainly, our journey turned out worse than we had expected. The ground was soft and wet, and very uneven, at the best, added to which we came every now and then to swollen streams, often so deep that we had to follow them some distance up to find a practicable crossing among the ice of the lakes. The constant detours, again, took up so much time that we had little left for hunting, and had to reduce our rations and those of the dogs accordingly. Igjugarjuk and the lake party had simply to follow the river and we were supposed to come up with them every evening. Actually we often failed to make their camp in time, but Igjugarjuk always waited faithfully till we did come up, and gave us directions for the next day's route. On one occasion we came within a hair's breadth of losing the canoe with its precious load. We had just got in to camp, on the bank of a stream flowing into the main river, and found that our companions had laid out some newly slain carcases on the other side. Crossing in the canoe, we suddenly perceived the dogs making straight for the meat, and in hurrying to save it, we omitted to pull the canoe far enough up shore; when we turned, it was floating rapidly away down to the main channel. Guns, ammunition, cameras, diaries, and everything of value was on board; in addition to which, the canoe itself was our only practicable means of transport.

The feverish chase that followed was beyond description. Igjugarjuk,—who, by the way, could not swim—joined me in a mad obstacle race in and out of water, each of us with one end of a line fastened round the body. There were masses of loose ice in the fairway, and I managed to swim from floe to floe, hauling up Igjugarjuk to each before making for the next. So we went on, clambering and struggling desperately in pursuit. Fortunately, the canoe itself was checked in its progress by these same masses of ice; nevertheless, we dared not relax our efforts. Our hands were torn and bleeding from the sharp ice crystals; and when at last we reached the canoe itself and dragged it into safety, we were so exhausted that we sank down helplessly beside it. Another few yards and it would have been carried into the main river, to certain destruction—and ourselves with it.

I noted a curious thing in connection with this little adventure, as showing the effect of intense effort and strain on the sense of time. Both Igjugarjuk and I agreed that the struggle could only have lasted some few minutes. But when our friends came up and got us back to camp and boiling hot tea, we found that the actual chase, from the time the canoe broke loose to its recapture had taken us two and a half hours.

On the 3rd of July we reached the settlement of Nahigtartorvik. I was anxious to push on, and made a detour to avoid the settlement. Unfortunately, however, our way was barred by a stream so deep and wide that there was no crossing it without the canoe, and we had therefore to camp and wait for the others. When they came up, Igjugarjuk reported that the country ahead of us was destitute of game, and there was famine lower down the Kazan River, where several families had died of starvation already. Moreover, the river was now in a dangerous state owing to masses of ice coming down from above. Birket-Smith and Bangsted with their party had gone by a few days before, and had difficulty in getting through; it would be worse for Igjugarjuk with only a couple of lads, his wife and two small children. It was therefore agreed that he should go on with me for two days more, after which I could manage by myself. First of all, however, we must call at the settlement and obtain food for myself and the dogs.

Pukerdluk, the headman of this particular village received us most hospitably. The caribou hunting had been very successful, and they were well off for meat. They gave us an excellent meal, and we had no difficulty in making arrangements for further progress. Pukerdluk himself was to go on with Igjugarjuk the next day, and a young man named Kijoqut—a remarkably handsome young fellow by the way—was to accompany us down to Baker Lake.

Next day, after a hearty farewell to Igjugarjuk, and not least, to his wife, who had looked after us like a mother, we set off overland to the spot where we were to meet the canoe. The same evening we drove up into the native camp on the Kazan River at the point where we were to cross. Contrary to the usual procedure, no one came out to meet us, and there was no answer to the vociferous barking of our dogs.

On entering the tent, we found the explanation and a sorry one indeed it was. Half a score of human figures lay about in various attitudes, all in such a stage of exhaustion that they could not walk. We at once made some tea, and when they had had as much as they could drink, they livened up a little. It was an extraordinary instance of Eskimo limitations thus to find men at the point of death in a starvation camp within a few miles of plenty.

Hilitoq, the head of the party, whom we had met before, and his two young sons, were not quite so far gone as the rest, and we persuaded them to come out hunting with us the same night. After some hours search, we came upon a herd of fourteen caribou; we shot three, and sent one back to Hilitoq's people at the camp.

It is difficult for a Greenlander to understand how these natives here can give up and lie down to die in a country so rich in game. But it is not laziness. I fancy the wretched footwear they use in summer has a great deal to do with it. They have not the thick stout sealskin or walrus hide, but only light caribou skin, pleasant enough in winter on the cold dry snow, but miserably inadequate in the swampy tundra during summer, and with no sort of wear in it over rocky ground; a couple of days will wear through perfectly new soles.

Late that night we reached the river Kunuag. After a difficult crossing, we took leave of our companions, who with their kayaks on their heads hurried back to their own people. We built a great fire, and roasted steaks of freshly killed meat on flat stones. All was clear ahead now, down to Baker Lake; the weather was fine, and as sleep is not so essential in summer, we were soon on our way once more.

It was slow going over the swampy tundra, that squelched underfoot at every step. By six the next morning we reached a group of three tents, and were surprised to find the inmates here also on the verge of starvation. We had the better part of two caribou carcases with us, and seeing no reason to carry a heavier load than needed, we invited the village to a feast. The fine fresh meat was disposed of with remarkable celerity, and I had once more an opportunity of witnessing the feats of which an Eskimo is capable in this direction. Hunger however, had by no means impaired the spirits of these

We were past astonishment when a gramophone was produced, and kept going for the rest of the afternoon. The natives declared, in sober earnest, that jazz tunes were no less comforting to an empty stomach than soothing to a full one.

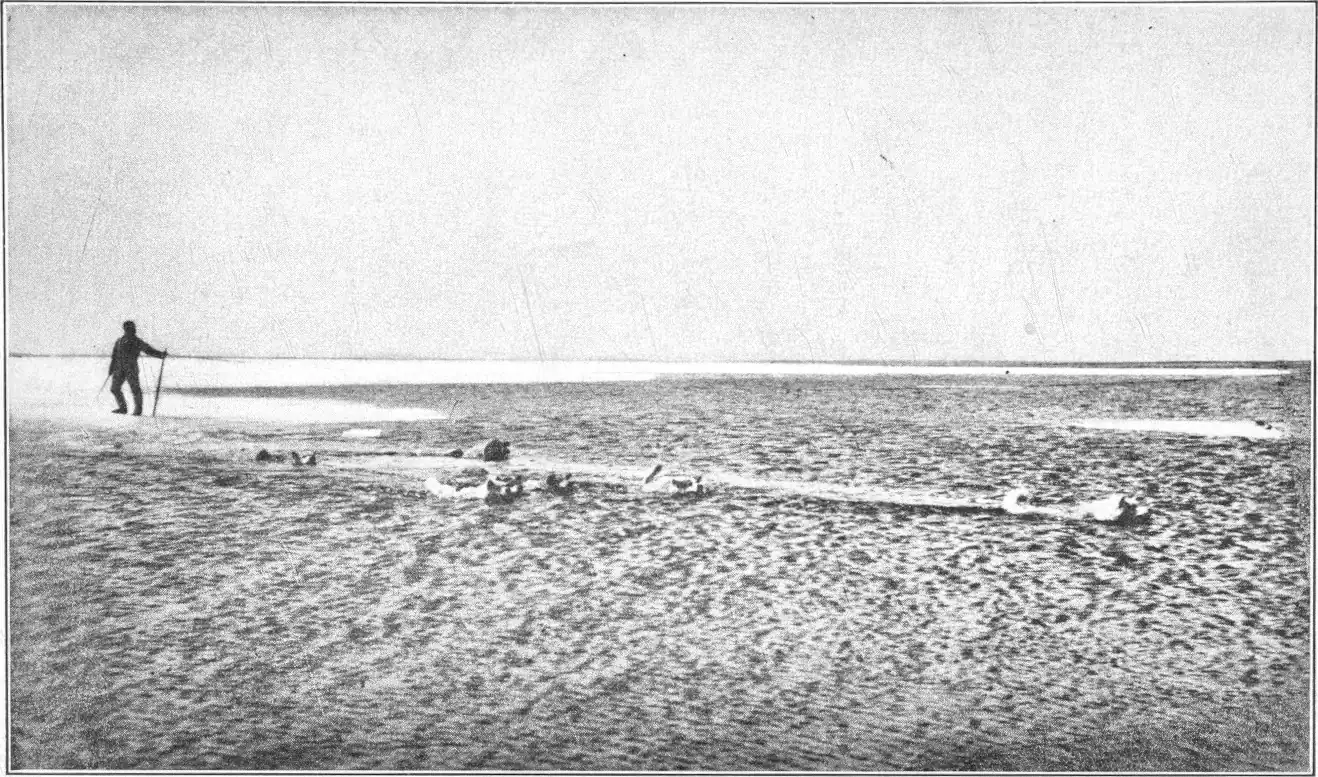

We had hoped to push on from here without further delay, but many obstacles lay between us and our return to Chesterfield,—too many to recount. The partial break-up of winter ice meant for us that progress by boat and progress by dog sledge were alternately barred. Once, native kayaks which we hired were crushed in the rocky narrows of a swollen river. Again, we had to cross a lake on a block of ice, with our dogs drawing the whole mass across by swimming in harness. And when, after days of soggy going, we finally reached Baker Lake, we could not rouse the people of the trading post out on the island, though we burned signal fires for eight hours continuously. So we finally ferried across on an ice floe, using our skis as paddles.

We found Birket-Smith and Helge Bangsted at the island, but they wished to continue their botanical studies, so we pushed on to Chesterfield without them. We met with more delays on the way down. to the Inlet,—chiefly from ice jams,—and not until July 31 did we reach our destination.

We had first visited Chesterfield in winter, and passed it in a blizzard, when everything was as arctic as could be; when one's nostrils froze in the icy blast and the blood fairly hardened in one's cheeks. Our own experience had taught us to appreciate the natives' power of adapting themselves to their surroundings. Their extraordinary clothing, of soft caribou skin from head to foot, inside and out, enabled not only the men, but also women and children, to move abroad in all manner of weather; as long as they could manage to procure food enough, the cold of winter seemed hardly to affect them at all.

Coming back now, in the summer, we found all changed to a surprising degree. The handsome dresses of caribou skin, so admirably suited to the racial type of the wearers, and to their surroundings, had given place to the cheap and vulgar products of the trading station. The men went about in jerseys and readymade slacks, their flowing locks surmounted by a cheap cloth cap, while the women had exchanged their quaint swallow-tailed furs, long boots and baggy breeches, for shapeless European dresses of machine-made stuff, in which grace and character alike were utterly obliterated.

So also with their dwellings; the wonderful snow huts, fashioned, as it were, of the cold itself as a protection from the cold, were now replaced by big white canvas tents, which made the place look more like a holiday camp than an Eskimo settlement. And one could not go near them without finding one's ears assailed by the noise of some modern mechanical contrivance, either a gramophone or a sewing machine.

I noted now for the first time how oddly these quondam inland folk—they were mainly from the neighborhood of Baker Lake—felt lost and out of their element here on the shore of the open sea. Just outside Chesterfield Inlet was a veritable highroad for the seal; and all round the adjacent Marble Island the walrus might be seen blowing and steaming at the surface of the water; yet never a man in all the settlement went out hunting either. The natives here, despite their astonishing agility and skill with kayak and spears among the turbulent waters of the rivers, were content now to let all this meat go by, while they themselves lived on tea and pancakes. The most they ever attempted in the way of hunting was to lay out a net in the bay just outside their tents and catch a few fish.

This indifference to the abundance offered them by the sea was not due to laziness however, but rather a peculiarity of their inland culture itself. They could not dispense with their caribou; and it was a principle handed down through generations that one could not mingle sea hunting with that of the land without losing the latter altogether.

After a pleasant two-weeks stay at Chesterfield, during which Birket-Smith and Bangsted rejoined us, and during which we received and sent off letters by the Hudson's Bay steamer, Nascopie, we set off on the long journey back to headquarters at Danish Island. It was already later in the summer than I wished, and plans which we had hopefully made for spending the summer in useful work together began to grow impracticable. I was anxious to see what the rest had been doing,—Mathiassen and Freuchen in their investigation of ancient culture, particularly.

We were fortunate in getting passage by motor-schooner as far as Repulse Bay, which we made in three days. Here we should, by agreement, have found Peter Freuchen encamped waiting for us with the motor boat we had built especially for summer work. The migratory ice, however, had kept him from getting out with it.

We accordingly hired a whaleboat belonging to an Eskimo from Southampton Island, who was known to the traders as "John Ell." As it turned out, we needed him for various errands during most of the winter following, so we grew to know and admire John Ell.

He was a man in many ways unlike the average type of native, having been educated to begin with on board a whaler, thus learning not only to speak English fluently, but also to manage a boat with remarkable skill, especially among the ice. He was looked up to as a leader by his fellows, and was also a man of property, having a fine team of dogs and a range of sledges designed for work at different seasons, a well-equipped whaleboat, and furthermore, a motor boat of his own. This last is uncommon among the Eskimos; John Ell had bought it for 75 fox skins. He carried on an extensive correspondence with people in the neighborhood, using the sign language invented by a missionary named Peck, which is here generally employed. And he kept a regular account of his income and expenditure throughout the year. It was the more remarkable, seeing how much he had lived and learned among white men, to find that he was a distinguished angakoq, with a faith in native magic equal to his reputation.

Winter weather on land and ice in the channel held us at Repulse Bay till September I, and then we crossed in a day as far as Hurd Channel. Here again we were held up for twelve days. We used the interval in hunting meat for our dogs, and other employments. Then we crossed at a favorable moment to Vansittart Island, and three days later got through to headquarters.

We found an empty house. Whereas we had expected a rousing welcome after our long absence, there wasn't even a letter to tell us where our other comrades were.

However, Freuchen and the Eskimos were only out at the hunting grounds, and they hadn't believed that we could get through the broken ice. We went out and found them, and our reunion was as joyous as any meeting in the Arctic is likely to be between companions long separated.

Mathiassen, with Jacob Olsen, was still at Southampton Island studying the traces of former Eskimo culture. It was not until February 18, and only after causing us anxiety for his safety, that he finally returned, and completed the final reunion of our party.

Meantime, the rest of us were held at Danish Island, or nearby, for most of the winter. Freuchen, who started out in January for Baffinland, to begin studies later to be carried out in cooperation with Mathiassen, was quickly brought back with a bad case of frostbite which made him temporarily an invalid. Birket-Smith and Bangsted were held at headquarters looking after him.

I was occupied during the winter with two main tasks,—completing my study and comparison of the various ethnographical collections, and rounding them out with materials secured on another visit to the natives around Lyon Inlet.

With regard to one item of our study, I felt that we had already secured satisfactory data; namely, the investigation of the culture of the Tunit. Therkel Mathiassen's work[1] here proved to be of greatest importance to our study of the people and their history as a whole.

There are no written sources for the early history of the Eskimo people; it is to the spade that we must turn if we would learn something of their life in ages past. We have to dig and delve among the ruins of their dwellings, in the kitchen middens of their settlements, for proof of how they lived and hunted, how they were housed and clad. It is often a laborious task, but not less interesting on that account. And it was one of the principal tasks of the Fifth Thule Expedition to investigate, by means of archæological excavations, the history and development of the Eskimo people, and their migrations into Greenland. Our work in this field has brought to light. some six or seven thousand items which afford a good

Naujan lies on the northern shore of Repulse Bay, a little to the east of the trading station. The name, which means "the place of the young seamews," is taken from a steep bird cliff on the banks of a small lake. From the lake, a valley runs down towards the shore, where it opens out into a bay, and it is in this valley, just south of the lake, that the great settlement of Naujan existed in ancient times.

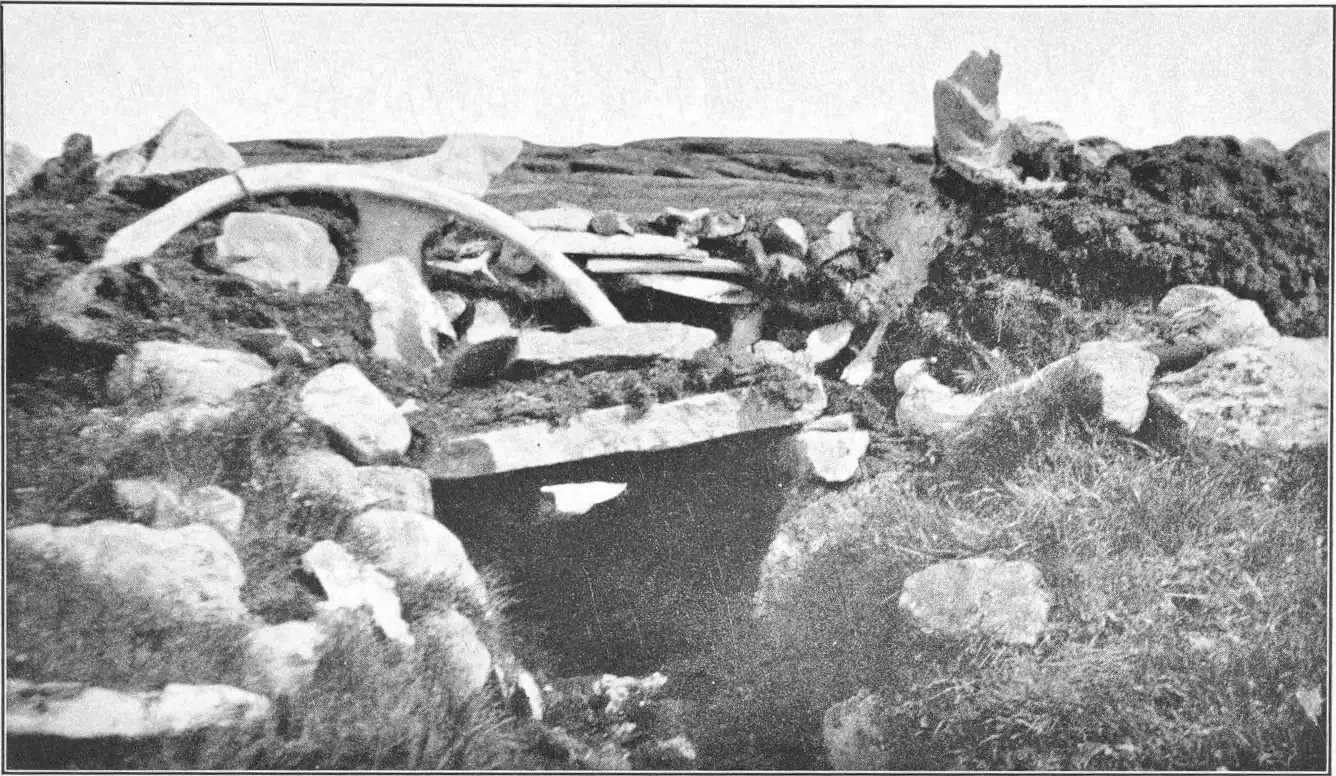

The Eskimos of the present day in these regions use only snow huts in winter; it was the more surprising therefore to come upon remains of quite a different type of house. We found at Naujan a whole little township of these houses, constructed of stone, turf, and the bones of whales. They were built so as to be partly underground and must have been far more substantial and warm, though less hygienic perhaps, than the light, cool, healthy snow huts of today. Various features placed it beyond question that at the time when these houses were built, the land must have lain some ten metres lower than it does now; and this, too, explains why the settlement was found at some distance from what is now the beach, instead of practically on it as is customary. Similarly, in confirmation of our theory, we found, on a little island near by, a pair of kayak stands—pillars of stone on which the skin kayaks are laid to be out of reach of the dogs—some 15 metres up from sea; actually, of course, they would have been built at the water's edge, to save hauling up and down.

The houses themselves had fallen to pieces long since, and the remains were scattered, weatherworn and overgrown with grass and moss to such an extent that our excavations gave but a poor idea of their original appearance. The implements and objects found among the ruins, however, gave an excellent view of the culture of the period from which they were derived. The materials comprised bone, walrus tusk and caribou antler, flint, slate and soapstone, whalebone, some wood, and occasionally metal, this last in the form of cold hammered copper (probably obtained by barter from the Eskimos of the west), with a single fragment of meteoric iron forming the point of a harpoon.

It is of course impossible to mention more than a very few of the finds here; often, too, the most insignificant objects to all outward seeming prove most important from the scientific point of view. Among our most valuable finds, for instance, were three odd broken fragments of rough earthenware vessels. These are only known to exist among the Alaskan Eskimos, and the finding of them here was of importance; few, however, would have attached any value to those three dirty scraps of pottery.

And now as to the age of this Naujan material. We may at once assert that nothing was found which could suggest any intercourse with Europeans. There were no glass beads—which are ordinarily the first thing the Eskimos procure, and always found in their villages—and the only fragment of iron found was of meteoric origin. This at once carries us back 300 years. Beyond this, we have only the alteration in the level of the land to fall back upon. It takes a considerable period, of course, for the land to rise ten metres, but there is no definite standard by which to measure the lapse of time involved. In the north of Sweden, for instance, the land rises I metre in a hundred years; allowing the same rate of progress here, this would give us an age of 1000 years—but this is, of course, mere guesswork.

As to the people who lived here in those days, they were beyond doubt genuine Eskimos; they lived on the shore in regular winter dwellings, drove dog sledges, and hunted whale, seal and walrus, besides bear and caribou; they trapped foxes, and caught salmon. They had at any rate no lack of meat, to judge from the enormous quantities of bones, which indeed, almost smothered the remains of the houses themselves. If we ask the present inhabitants of these regions, the Aivilik, as to the folk who dwelt in these now ruined houses, they will say, it was the Tunit. These Tunit were a race of big, strong men who lived in permanent dwellings and hunted whale and walrus; the men wore bearskin breeches and the women long sealskin boots just like the Polar Eskimos of today. When the Aivilik settled on the coast, the Tunit moved away to the northward; only on the inaccessible Southampton Island did a party remain, and the Sadlermiut, who died out here in 1903, were the last descendants of the Tunit in the country. Thus the Aivilik tradition, and it agrees in all essentials with the results of our investigations.

For on comparing these Tunit of ancient Naujan with the present inhabitants, we find a great difference between them. The Naujan Eskimos lived on the shore, hunted the whale, and built their houses from the skeletons. The Aivilik live in snow huts, and spend most of the year hunting caribou up in the interior. Many of the implements and utensils in use among the Naujan folk, such as the bola, the bird dart, and earthenware vessels, are unknown among the Aivilik; the latter, on the other hand, have others unknown to the ancients, such as combs, big ladles made of musk ox horn, and toggles for dog harness. And on examining the types of implement in use among the two peoples, many distinct points of difference are found.

Where did the Naujan Eskimos come from, and what became of them?

It soon becomes apparent that they link up in two directions across the Eskimo region; with Alaska on the one hand and Greenland on the other. At Thule, in northern Greenland, a find has been made, the oldest of any extent from the whole of Greenland, which points to precisely the same type of culture as that which we found at Naujan; and we have therefore called it the Thule type. Similar finds have been made both in west and north Greenland, and the Polar Eskimos of the present day are very much like these Thule folk in many respects. The Greenland Eskimos, then, must have passed through these central regions at a time when they were still inhabited by the Thule folk.

Looking now to the westward, we find in Alaska a race of big men, who hunt the whale, live in permanent dwellings on the coast, use the bola, make earthenware, and have almost the same types of implements generally as those we found at Naujan; old finds from Alaska also exhibit even more marked resemblance to the Naujan type. The Thule folk then, must have come from Alaska, this is beyond question. They spread in a mighty wave from west to east, reaching right across to Greenland. At some time now far distant there was a more or less uniform type of culture prevailing throughout the whole of the Eskimo region; that which we now call the Thule type; then, in the central districts, an advance took place of people from the interior represented by the present-day Central Eskimo: the Aivilik, Netsilik, Copper Eskimos and Baffinlanders. These people, with their culture based on snow huts and caribou hunting, made their way down to the coast, where their mode of life was gradually adapted to some extent, so as to include the hunting of marine animals, while the ancient Thule culture disappeared from the central regions where now only the numerous ruins of stone and bone houses remain as evidence of the culture of earlier times. Thus too we have an explanation of many otherwise inexplicable similarities between the two topographical extremities of Eskimo culture; Alaska and Greenland; features found in the extreme east and in the extreme west, but lacking in the central region.

- ↑ Space forbids the inclusion here of my companions' reports in full, and I can give but the briefest indication of their main features. Both Freuchen's and Therkel Mathiassen's reports are published-or shortly to be published—in English elsewhere. The pages here following are taken from Therkel Mathiassen's own text.