Across Arctic America/Chapter 9

Chapter IX

Faith Out of Fear

By the middle of January, I had the ethnographical collections in shape so that I could leave Danish Island for good. But we still needed a few items. I wanted a few more skin dresses to round out the collection, and I wished to make a final study of the spiritual beliefs of the Eskimos of the region. Accordingly, I set off for the hunting camp at the mouth of Lyon Inlet, to visit my old friend Aua.

Aua's hunting camp lay midway out in Lyon Inlet; I reached it late one afternoon, just as the setting sun was gilding the domes of the snow huts.

It was known that I was on the way, and above each hut waved a little white flag—a sign that the inmates had relinquished their old heathen faith and become Christians. As I drove up, men, women and children trooped out and formed up in line outside Aua's hut, and as soon as I had reined in my team, the whole party began singing a hymn. The tune was so unlike what they were accustomed to in their own pagan chants that they bungled it a little, but there was no mistaking the earnestness and pious feeling which inspired it. There was something very touching in such a greeting; these poor folk had plainly found in the new faith a refuge that meant a great deal in their lives.

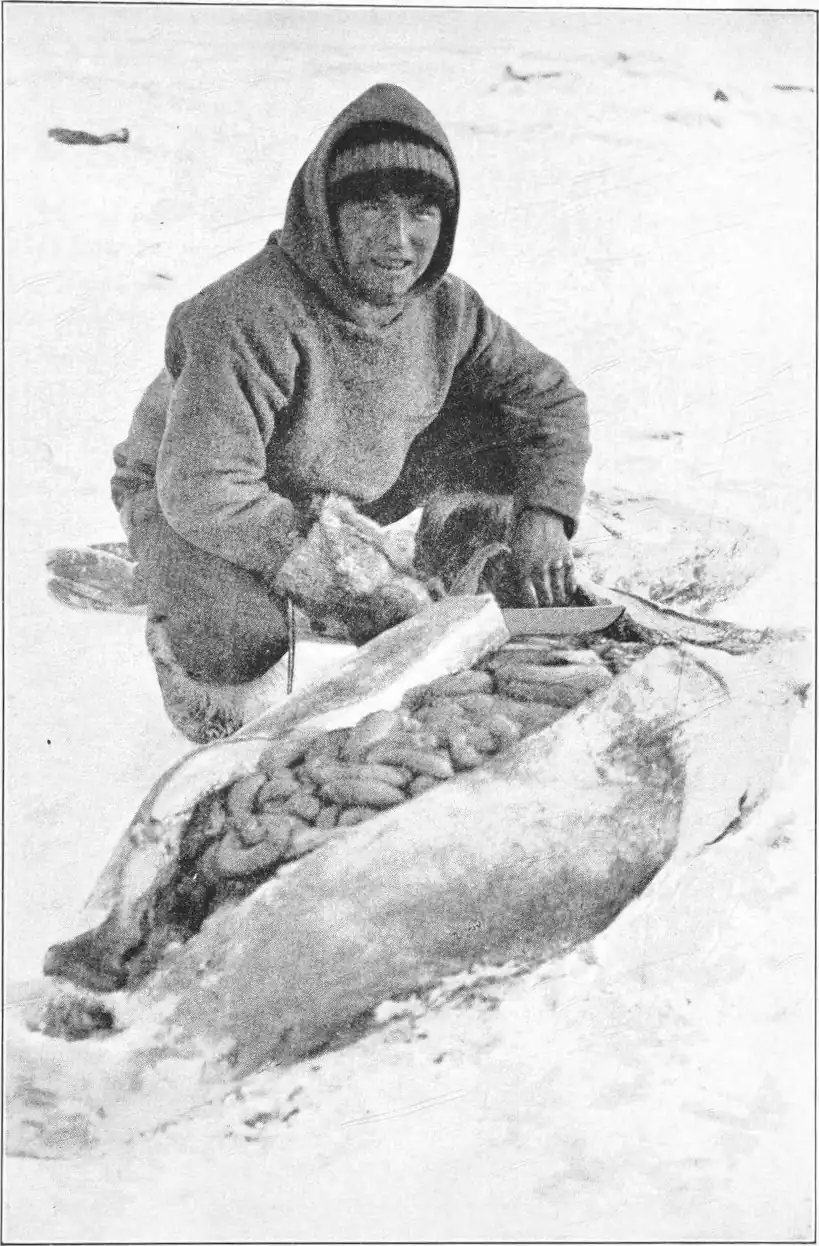

When it was over, they stepped forward one by one and shook hands. And here I could not but recall my first meeting with these same people a year ago, at Cape Elizabeth. Then, they had come leaping and capering round me in an outburst of unrestrained natural feeling; now, all was ceremonial and solemn to an almost painful degree. It was not long, however, before this wore off, and the old easy merriment showed forth again. The carcase of a seal was brought out and thrown to the dogs, and while they were busy with it, I was regaled with the latest news. Then my sledge was hoisted up onto a stand built of blocks of snow, and I myself invited indoors to thaw. Aua's wife, Orulo, good friendly soul, had a fine big bowl of steaming hot tea for me, and when this had driven out some of the cold I could settle down at ease among my old friends.

It was the most difficult time of the year just now; the stores of meat accumulated during summer had been used up, and it was a question of procuring fresh supplies for men and dogs, from day to day. Seal were hunted now either at the breathing holes or in the open water beyond the edge of the ice. The weather was rough and stormy, snow falling every day, and the thermometer rarely above minus 50°C. The days were short, and in order to make the most of them, the hunters set off before daylight and returned after dark. All meat brought in was cut up and distributed at once throughout the camp, and as there was generally no more than would suffice for one day, the arrival of the next instalment was looked forward to with anxiety literally equal to that with which hungry folk look forward to a meal.

The men had little rest these days. It is a weary business to be out for ten hours at a stretch, first searching about to find the blowhole of a seal, and having found it, to stand motionless in the driving snow waiting for the seal to come up to breathe. A seal has always a number of blowholes open at once, and it might often be hours before it appeared at the one actually under observation. No wonder then, that the hunters were stiff and sore by the time they returned. Throwing off all but their innermost clothing, they threw themselves down on the bench in the warmth of the hut, while the women busied themselves cutting up the carcases into juicy red fillets edged with rich yellowish blubber. Then, when the pots began to boil, came the reward of the day's toil, in the shape of a steaming cup of thick blood-soup. The next course was meat, speared up from the cauldron on long bone skewers, and dumped down upon a wooden tray enriched with the juices of many a former meal. A sense of warmth and comfort spread and grew, the little triumphs or disappointments of the day were recounted with good humor; material wants were satisfied for the time being, and peace and plenty reigned.

These evenings, when we lay stretched at ease after a hearty meal, and the most taciturn had thawed into some degree of geniality, were the times I most looked forward to for converse with my hosts.

In the collecting of folk lore, one is altogether

In addition to Aua himself, there were three other wizards in the camp, differing considerably in type and character. I endeavored throughout as far as possible to get them to take part in the conversation, in order to obtain as varied a general view as possible. One of them was a young man named Anarqaoq. He was not particularly skilful as a hunter, and had been more or less of a vagabond all his life. He had come originally from one of the Netsilik tribes in the neighborhood of King William's Land, where his first introduction to the practice of magic had taken place. He was a man of a very nervous temperament, easily influenced, and his speciality, as one might say, consisted mainly in the remarkable visions which came to him as soon as he was out alone caribou hunting in the interior. His imagination peopled the whole of nature with fantastic spirit creatures that came to him either while he slept, or even when fully awake and engaged on his normal occupations. In some way he could not explain, these spirits gave him an enhanced power of penetrating into the realms of mystery; and though his own accounts of such experiences often appeared naïve to say the least, they sufficed to impress his fellows with a sense of his importance as one familiar with the unknown powers. I gave him a pencil and paper one day and asked him to draw some of these "visions." After some hesitation he complied. And I could not but feel that he was himself convinced of their reality; he did not simply sit down and draw the things at once, but would remain for some time manifestly under the influence of strong emotion, trembling often to such a degree that he could hardly draw at all.

It is difficult indeed for the ordinary civilized mentality to appreciate the complexity of the native mind in its relations with the supernatural; a "wizard" may resort to the most transparent trickwork and yet be thoroughly in earnest. Anarqaoq himself, afforded an instance of this. One evening a child came in crying, but unable to say what was the matter—a not uncommon happening with children as everyone knows. Our wizard, however, grasped and utilized the opportunity. He dashed out into the darkness and returned some time later covered with blood and with great rents in his clothing, having fought and defeated the "evil Spirits" that were seeking to harm the child. No one suspected that he had snatched up a lump of half frozen seal's blood from the kitchen, and with this, and a few self-inflicted wounds upon his garments, supplied the needful evidence to impress his fellow villagers with the truth of his story.

Another wizard was Unaleq, also a Netsilik. I chose out these two in particular for occasional interrogation because the Igdlulik, to which tribe Aua himself belonged, regarded the Netsilik as their inferiors, and Aua was thus impelled to be more communicative himself.

Unaleq was, I think, the most trustful and optimistic soul I have ever met. Actually one of the poorest and most unskilful hunters for some distance round, he was nevertheless convinced that his "helping spirits" had endowed him with supernatural powers enabling him to assist his fellows. I got him to draw these spirits for me, as Anarqaoq had done, though again, not without considerable difficulty, despite the tempting nature of the prize offered—a knife bigger and brighter and sharper than he had ever owned in his life. When he had finished, I assured him that he would be successful in his hunting on the following day, as I had dreamt I saw him catching a seal. Whether due to laziness or lack of skill, he had caught not a single seal all that winter. But on the following day he did. The confidence with which my dream inspired him had, perhaps, encouraged him to effort beyond his usual capacity; at any rate, he brought home a seal.

And finally, there was Aua's brother, Ivaluartjuk, whose contribution to our stock of legends and myths was of the greatest value. We met him for the first time at Repulse Bay. He was a duly qualified wizard, but rarely practised his art, his speciality being folk tales, of which over fifty were written down from his dictation. Space forbids the inclusion of further stories at length, but there is one important point in this connection which must be noted, to wit, the similarity, or indeed, identity of many of the Canadian Eskimo folk tales with those already known from the Eskimos of Greenland. A few instances have been noted in the foregoing; and the further evidence afforded by this later material places the question of kinship beyond all doubt. The following are a few of the themes in the stories told by Ivaluartjuk having counterparts or very close variants in different parts of Greenland:

The coming of men: at the very beginning of the world, women went out and found children sprawling among the bushes. Later, they grew to be many throughout the world.

Day and night. In earliest times, all was dark; the fox wished it to be dark that it might steal from the dwellings of men. But the raven could not see to find food in the dark, and wished for light. And there was light.

The raven that married a goose, and was drowned when the birds flew over the sea.

The fatherless boy who was ill-used by his fellows, till a spirit (the moon) took pity on him and made him a strong man, when he returned and took vengeance.

Igimarajugjuk, who ate his wives.

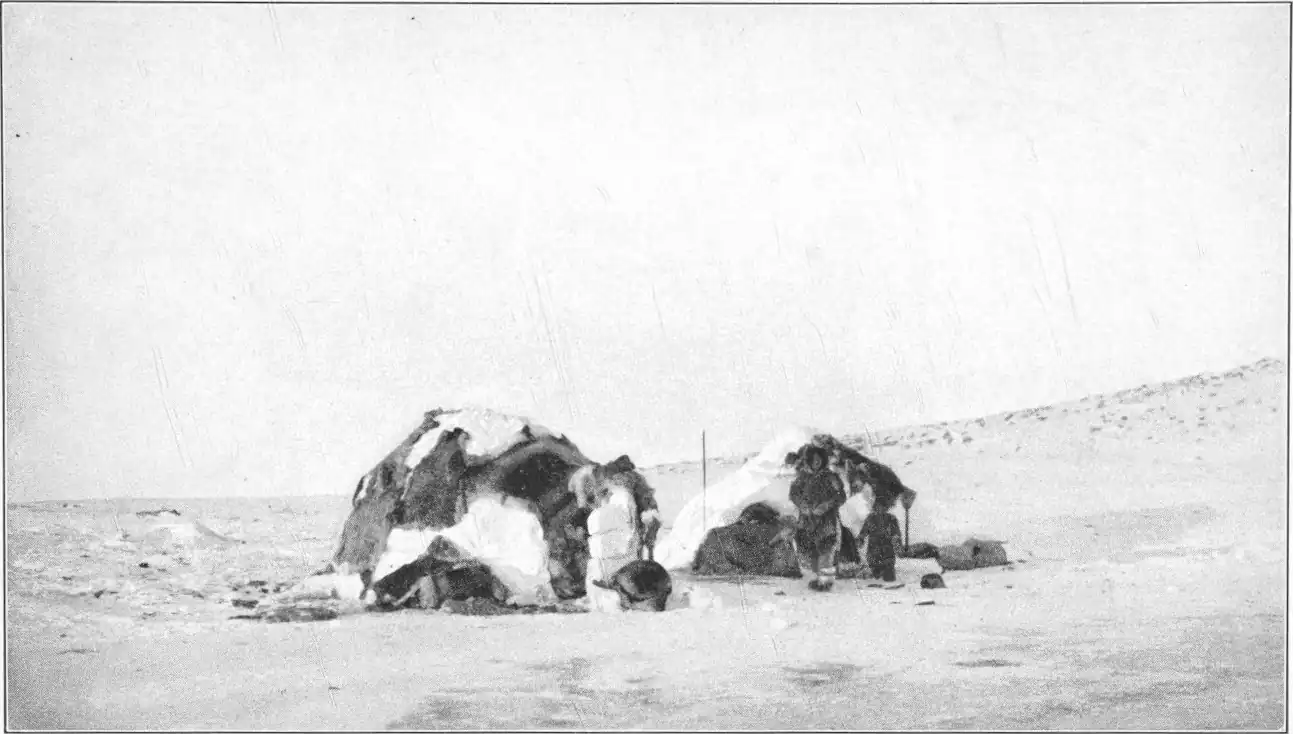

SNOW HUTSThese are built with the first snows of autumn. Skins of newly killed caribou are hung out to dry.The soul that lived in the bodies of all beasts.

Sun and moon—brother and sister who loved each other, till the sister, ashamed, fled away by night, the brother in pursuit. Both carried torches, but the one went out, hence the faint glow of the moon compared with the sun.

The man disturbed in his hunting by children at play; he shuts them up in a mountain where they starve to death.[1]

There are, of course, numerous themes common to the folklore of many different countries and races, so that the subject itself does not always count for much. But in the case of these stories we often find, not only close resemblance in points of detail, but precisely identical words in the dialogue.

Aua of course, as a wizard himself, was an authority not only on folklore and customs generally, but more especially on all matters connected with the supernatural, as well as the complicated rites and observances coming under the head of tabu. His account of the origin of his own profession is worth noting. Briefly, it was as follows:

In very early times there were no wizards, and people generally were ignorant of many things pertaining to their welfare. Then it came about that there was great famine at Igdlulik, and many died of starvation. One day, many being assembled in one house, a man there present declared that he would go down to the Mother of the Sea. None of those present knew what he meant by that. But he insisted, and begged to be allowed to hide behind the skins, as he was about to undertake something for the good of all. They allowed him to do so, and presently, pulling the skins aside, they saw that he was already almost gone, only the soles of his feet remaining above ground. It is not known what inspired him to do this thing, but some say he was visited by spirits that came to him out in the great solitude. And he went down to the Mother of the Sea, and brought back her good will and the grant of game for the hunters, so that thenceforward there was no longer dearth, but great abundance of food, and all were happy once more. Since then, the angakoqs, have learned much more about hidden things, and aided their fellows in many ways. They have too their own sacred speech, which is not to be used for common things.

A young man wishing to become an angakoq must first hand over some of his possessions to his instructor. At Igdlulik it was customary to give a tent pole, wood being scarce in these regions. A gull's wing was attached to the pole, as a sign that the novice wished to learn to fly. He had further to confess any breach of tabu which he might have committed, and then, retiring behind a curtain with his instructor submitted to the extraction of the "soul" from his eyes, heart and vitals, which would then be brought by magic means into contact with those beings destined to become his helping spirits, to the end that he might later meet. them without fear. The ultimate initiation always took place far from all human dwelling; only in the great solitude was it possible to approach the spirits. Furthermore, it was essential that the novice should start young; some, indeed, were entered to the profession before they were born. Aua himself was one of these, his mother declaring that her coming child was one that should be different from his fellows. His birth was attended by various remarkable features, special rites were observed, and strict discipline imposed on him during childhood and early youth; "nevertheless, though all was thus prepared for me, I tried in vain to become an angakoq by the ordinary methods of instruction." Famous wizards were approached and propitiated with gifts, but all in vain. At last, without knowing how, he perceived that a change had come over him, a great glow as of intense light pervaded all his being (this is a recurrent feature in the process) and a feeling of inexpressible joy came over him, and he burst into song.

"But now," he went on, "I am a Christian, and so I have sent away all my helping spirits; sent them up to my sister in Baffin Land."

Occasionally, the spirits themselves lay hold of a man and of their own accord invest him with supernatural powers; this is generally reckoned as a painful process, attended by terrifying phenomena.

It is the business of an angakoq to heal the sick, to protect the souls of his fellows against the machinations of hostile wizards, to intercede with the Mother of the Sea when seal are scarce, and to see that traditional customs are properly observed. Infantile diseases, for instance, are generally reckoned as due to some breach of tabu on the part of the mother; famine may likewise be sent as a punishment for similar neglect, and the angakoq has then to find and persuade the culprit to confession.

Such manifestations as I had an opportunity of witnessing myself were, I must confess, disappointing to the critical observer. Acquainted as he would be with his neighbors' life and doings, it was not difficult for the angakoq to hit upon something done or left undone by one or another. The trance-like state into which he cast himself was not impressive in itself, and as for the spirits supposed to be present, one can only say they did not make their presence felt. The wizard stood in the middle of the hut with his eyes closed, talking in a strained, unnatural voice; the rushing of mighty wings, which in the old stories accompanies such spiritual visitations, was conspicuous by its absence.

I had frequently brought the conversation round to the subject of tabu with a view to ascertaining the purpose of these highly complicated and apparently meaningless observances; this thing insisted on, and that strictly forbidden. But here lay the difficulty. Everyone knew, and all were unanimously agreed, as to what must be done or avoided in any given situation, but as to the why and the wherefore, none could advance any explanation whatever. They seemed, indeed, to regard it as unreasonable on my part to demand, not only a statement, but a justification, of their religious rites and ceremonies. Aua was as usual the one I mainly questioned, and one evening, when I had been endeavoring to extract some more positive information on this head, he suddenly rose to his feet and invited me to step outside.

It was twilight, the brief day was almost at an end, but the moon was up, and one could see the storm-riven clouds racing over the sky; every now and then a gust of snow came whirling down. Aua pointed out over the ice, where the snow swept this way and that in whirling clouds. "Look," he said impressively, "snow and storm; ill weather for hunting. And yet we must hunt for our daily food; why? Why must there be storms to hinder us when we are seeking meat for ourselves and those we love?"

Why?

Two of the hunters were just coming in after a hard day's watching on the ice; they walked wearily, stopping or stooping every now and then in the wind and the snow. Neither had made any catch that day; their watching had been in vain.

Why?

I could only shake my head. Aua led me again, this time to the house of Kuvdlo, next to our own. The lamp burned with the tiniest glow, giving out no heat at all; a couple of children cowered shivering in a corner, huddled together under a skin rug. And Aua renewed his merciless interrogation: "Why should all be chill and comfortless in this little home? Kuvdlo has been out hunting since early morning; if he had caught a seal, as he surely deserved, for his pains, the lamp would be burning bright and warm, his wife would be sitting smiling beside it, without fear of scarcity for the morrow; the children would be playing merrily in the warmth and light, glad to be alive. Why should it not be so?"

Why?

Again I could make no answer. And Aua took me to a little hut apart, where his aged sister, Natseq, who was ill, lay all alone. She looked thin and worn, and too weak even to brighten up at our coming. For days past she had suffered from a painful cough that seemed to come from deep down in the lungs; it was evident she had not long to live.

And for the third time Aua looked me in the face and said: "Why should it be so? Why should we human beings suffer pain and sickness? All fear it, all would avoid it if they could. Here is this old sister of mine, she has done no wrong that we can see, but lived her many years and given birth to good strong children, yet now she must suffer pain at the ending of her days?"

Why? Why?

After this striking object lesson, we returned to the hut, and renewed our interrupted conversation with the others.

"You see," observed Aua, "even you cannot answer when we ask you why life is as it is. And so it must be. Our customs all come from life and are directed towards life; we cannot explain, we do not believe in this or that; but the answer lies in what I have just shown you.

"We fear!

"We fear the elements with which we have to fight in their fury to wrest out food from land and sea.

"We fear cold and famine in our snow huts.

"We fear the sickness that is daily to be seen amongst us. Not death, but the suffering.

"We fear the souls of the dead, of human and animal alike.

"And therefore our fathers, taught by their fathers before them, guarded themselves about with all these old rules and customs, which are built upon the experience and knowledge of generations. We know not how nor why, but we obey them that we may be suffered to live in peace. And for all our angakoqs and their knowledge of hidden things, we yet know so little that we fear everything else. We fear the things we see about us, and the things we know from the stories and myths of our forefathers. Therefore we hold by our customs and observe all the rules of tabu."

Aua's explanation was reasonable enough from his point of view. There was no more to be said.

But I will endeavor now to give a brief summary of the leading principles in the system of tabu, with its ordinances and prohibitions.

It is to begin with very largely a matter of propitiatory rites and ceremonies attending the treatment of the animals killed; preparing food, skins, etc. Here, there is a fundamental distinction between land game and the products of the sea. The fauna of each has its own distinct origin, and it is believed that any contact between the two is offensive to both, involving punishment of the person responsible. The caribou of the land have their "mother," as the seal and walrus together have theirs, and the two must never be confused.

Then it is a matter of faith that all living creatures have souls; and the souls of animals slain for food or other useful purpose by man are affected by the manner in which their bodies are treated after death; even, indeed, by the manner of their killing. There are a host of little apparently trivial things that must be done or must on no account be done, in connection with hunting, cooking, making clothes and the like; and they are regarded so much as a matter of course that it is difficult, when living among the natives and observing them, to pick out this or that little matter and get at the purpose underlying it. The whole system is further complicated by "name" principle running through daily life and observances in a similar way. A person's name is always derived from that of someone deceased, and carries with it the namesake's qualities; one becomes, indeed, a member of the great community of all who have borne the same name back to the ultimate distant past. Each living human being is thus attended by a host of namesake-spirits, who aid and protect him as long as he is faithful to rule and rite, but become inimical on any transgression.

The soul of the caribou detests everything pertaining to the creatures of the sea; in caribou hunting, therefore, all implements and material associated, with hunting at sea must be left behind. On the other hand, footwear which has been used for caribou hunting must on no account be used when hunting seal or walrus. Caribou are moreover, peculiarly sensitive in regard to "contamination" by women; when slain, they must be skinned in such a fashion that certain parts of the carcase are protected against direct contact with a woman's hands. Women at certain periods, and in certain conditions, are forbidden to touch either the meat or the skin. Dogs must not gnaw the bones of caribou during the hunting season. A piece of the meat and a piece of the tallow must be placed under a stone near the spot where the animal was killed; this is an offering to the soul in the hope that it may attract other caribou to the hunter.

Walrus hunting has its own special rules, which again are to some extent distinct from those which apply to seal. Salmon, curiously enough, are reckoned as "land meat" and may not be eaten on the same day as seal or walrus meat.

Tabu at Igdlulik was particularly strict, as it was here, according to tradition, that the Mother of the Sea met with her fate, and she is thus nearer and more easily offended than elsewhere. It was said that she hated the caribou because they were not of her own creation; hence the rule that whale, seal and walrus meat must never be eaten on the same day as caribou; must not even be found in the same hut at the same time.

Some of the sea-beasts are of the "dangerous" order, and have to be propitiated after death; thus whale, ribbon seal and bear. No work may be done in the huts for so many hours after the killing; parts of the carcase must be hung up together with certain implements. Ordinary seal are easier to manage, but here again there are complicated rules as to refraining from this and that until it has been skinned. Certain articles must not be touched, women must not comb their hair. Sinews of the seal must never be used for sewing, on pain of premature death.

Birth and death have their own peculiar rites and observances. Various means are employed to facilitate birth, mainly of the magic order, such as the wearing of certain amulets, or dressing the hair in a certain way. No assistance may on any account be rendered to the woman at the actual birth; she is placed beforehand in a separate tent or hut, and there left until the child is born. She is then moved to another house where she lives by herself for two months; others may visit her, but she must not enter any other house. For a whole year after she is not allowed to eat raw meat, or the meat of any animal save those killed in certain ways. There are endless observances designed to secure good luck or useful accomplishments for the child when it grows up.

Death involves first of all the attendance of the nearest relatives for a period of three days if the deceased be a man, four days if a woman; during this time the soul is supposed to remain in the body, which must not be left alone. No work must be done, nor any hunting save in extreme need, during these first days of mourning. No one is allowed to wash, comb hair or cut nails. Curious methods are employed for purification of the hut or tent, and certain magic formulæ are used. The body is never buried or enclosed in a cairn, but simply laid out on the earth at the chosen spot, with a few loose stones placed at head, shoulders and feet. In winter, a small snow shelter may be built above the corpse. Models in miniature of implements used by the dead, suitable for man or woman as the case may be, are fashioned and placed beside the corpse for use "on the other side."

Persons tired of life and wishing to hang themselves—a recognized form of suicide—are required to do so while alone in the house, and by certain methods; it is also a rule that the suicide shall leave the lamp burning in order that his body may be at once observed as soon as anyone enters the hut.

A woman who has lost a near relative is regarded as unclean for a year after; she may not work on caribou skin, or speak of any animal used for food except in the peculiar terms employed for magic incantations. A man who has lost his wife may not drive or strike his own dogs for a year after.

When any breach of these irksome regulations has been committed, the only means of making reparation and warding off the evil consequences that would otherwise ensue, is for the delinquent to confess at once to his fellows. There is, however, a natural unwillingness to do so; and furthermore, the complexity of the whole code renders it very easy for one to offend unwittingly. Even where every reasonable care is taken, there is constant danger of incurring the enmity of spirits and supernatural powers; and it becomes the task of the angakoq, then to intervene.

All these observances however, are mainly negative; designed to avoid actual disaster; they do not make for any positive advantage beyond the ordinary level of security. He who would achieve anything further must have recourse to amulets and charms, or spells.

Amulets consists mainly of certain portions of the body of certain animals, which are sewn into the clothing. The Igdlulik natives, unlike those of Netsilik, use very few amulets, but their idea as to the purpose and effect is the same. The virtue lies in the soul of the creature represented, though it is only certain parts of its body which can convey the power. A woman with a newly born infant for instance, will use a raven's claw as a fastening for the strap of her amaut (the bag in which the child is slung on her back); this is supposed to give strength and success in hunting to the child later on.

The mystic power of an amulet is not invariably at the service of the person wearing it; the actual object for instance, may be given away to another, but its inherent activity will not operate on his behalf unless he has given something in return. It is a regular thing for a young hunter to obtain a harpoon head from some aged veteran no longer able to hunt for himself; the "luck" of the former owner then passes with the chattel to its new possessor. Clothes may be lucky in themselves. One lad at Igdlulik whose father was always unlucky at caribou hunting, was given the sleeve linings of a particularly successful hunter, and these were fitted successively to every tunic he wore, and brought him luck. There are amulets for various qualities, such as making the wearer a good walker, preserving him from danger on thin ice, keeping him warm in the coldest weather, giving extra stability to his kayak, and so on.

Then there are "magic words" for use in various emergencies. The efficacy of these is impaired as

Aua himself had, as a young man, learnt certain charms of this sort from an old woman named Qeqertuanaq, in whose family they had been handed down from generation to generation dating back to "the very first people on earth." And by way of payment Aua had undertaken to feed and clothe her for the rest of her life. They had always to be uttered in her name, or they would be of no avail.

Here is one of them, designed to lighten heavy loads. The speaker stands by the fore end of his sledge, looking ahead and says:

I speak with the mouth of Qeqertuanaq, and say:

I will walk with leg muscles strong as the sinews on the shin of a little caribou calf.

I will walk with leg muscles strong as the sinews on the shin of a little hare.

I will take care not to walk toward the dark.

I will walk toward the day.

(This may be said also when setting out on a journey on foot.)

A charm for curing sickness among neighbors may be uttered by one who is well. The speaker gets up early in the morning before anyone else is astir, takes the inner upper garment of a child, and drawing down his own hood over his head, thrusts his arms into the sleeves of the child's garment as if to put it on. Then these words are uttered:

I arise from my couch with the grey gull's morning song.

I arise from my couch with the grey gull's morning song.

I will take care not to look toward the dark,

I turn my glance toward the day.

Words to a sick child:

Little child! Your mother's breasts are full of milk.

Go to her and suck, go to her and drink. Go up into the mountain. From the mountain's top shalt thou find health; from the mountain's top shalt thou win life.

A charm to stop bleeding:

This is blood from the little sparrow's mother. Dry it up! This is blood that flowed from a piece of wood. Dry it up.

A charm for calling game to the hunter:

Beast of the sea! Come and place yourself before me in the dear early morning!

Beast of the plain! Come and place yourself before me in the dear early morning!

These charms, quaint or meaningless as they may seem, are used by the Eskimos in all sincerity and pious faith, as prayers humbly addressed to the mighty powers of Nature.

- ↑ A representative collection of these Greenland stories is given in Eskimo Folk Tales, by Knud Rasmussen and W. Worster, London, Gyldendal.