Across Arctic America/Introduction

Introduction

It is early morning on the summit of East Cape, the steep headland that forms the eastern extremity of Siberia.

The first snow has already settled on the heights, giving one's thoughts the first cool touch of autumn. The air is keen and clear; not a breeze ruffles the waters of Bering Strait, where the pack ice glides slowly northward with the current.

The landscape has a calm grandeur all its own; far away in the sun-haze of the horizon rises Great Diomede Island, here forming the boundary between America and Asia.

From where I stand, I look from one continent to another; for beyond Great Diomede lies, like a bank of blue fog, another island, the Little Diomede, which belongs to Alaska.

All before me lies bathed in the strong light of sun and sea, forming a dazzling contrast to the land behind me. Here lies the flat, marshy tundra, apparently a land of dead monotony, but in reality a plain-realm, with the life of the plain in game and sounds; a lowland which, unbroken by any range of hills, extends through a world of rivers and lakes to places with a distant ring, to the Lena Delta, and, farther, farther on, beyond Cape Chelyushkin, to regions that lie not far from my own land.

At the foot of the hill I have just ascended I see a crowd of Tchukchi women on foot, dressed in skins of curious cut; they have on their backs bags made of reindeer skin which they are filling with berries and herbs. They fit, as an item of detail, so picturesquely into the great expanse that I continue to gaze at them until they are lost to sight among the green slopes of the valley.

On a narrow spit of land, with pack ice to the one side and the smooth waters of the lagoon on the other, lies the village or township of Wahlen. It is only now beginning to wake; and one by one the cooking-fires are lighted in the dome-shaped tents of walrus hide.

Not far from the coast town, clearly silhouetted on the skyline, a flock of tame reindeer move slowly along the crest of a hill, nibbling the moss as they go, while herdsmen, uttering quaint far-sounding cries, surround them and drive them down to the new feeding grounds.

To all these people, this is an ordinary day, a part of their everyday life; to me, an adventure in which I hardly dare believe. For this landscape and these people mean, to me, that I am in Siberia, west of the last Eskimo tribe, and that the Expedition has now been carried to its close.

The height on which I stand, and the pure air which surrounds me, give me a wide outlook, and I see our sledge tracks in the white snow out over the edge of the earth's circumference, through the uttermost lands of men to the North. I see, as in a mirage, the thousand little native villages which gave substance to the journey. And I am filled with a great joy; we have met the great adventure which always awaits him who knows how to grasp it, and that adventure was made up of all our manifold experiences among the most remarkable people in the world!

Slowly we have worked our way forward by unbeaten tracks, and everywhere we have increased our knowledge.

How long have those sledge journeys been?—counting our road straight ahead together with the side excursions up inland and out over frozen seas, now hunting game,

In my joy in having been permitted to take this long sledge journey, my thoughts turn involuntarily to a contrasting enterprise ending also in Alaska, where last Spring, people were awaiting the visit of daring aviators from the other side of the globe. And from my heart I bless the fate that allowed me to be born at a time when Arctic exploration by dog sledge was not yet a thing of the past. In this sudden retrospect, kindled by the great backward view from East Cape, indeed, I bless the whole journey, forgetting hardship and chance misfortune by the way, in the exultation I feel in the successful conclusion of a high adventure!

A calmer and more deliberate mental review of that long journey brings almost as much regret as pleasure. For I find that to tell of my observations on the trip, in a book of proper length, compels me to omit more than I can include; and, often, things of great interest.

Particularly painful is it to leave out a statement of the accomplishments of my associates on the Expedition. At the beginning I was merely the leader of a whole group, which included some Danish scientists of note. During the first year, we worked together out of a base on the eastern coast of Canada, going out in small parties to various stations, and returning from time to time to collate our material. Our work had mainly to do with ethnography; my associates were concerned also with archeology, geology, botany and cartography. They did notable work in mapping territory known before only in a vague way. We did much excavating in ruins of former Eskimo cultures. The work of my colleagues in this field, especially, contributed much to knowledge of the past. Full reports of their findings have been published in books, monographs, and papers under their own names before learned societies. This allusion here must stand as the chief acknowledgment, in the present book, of their work. They enter hereafter only in passing.

For, here, I am constrained by limitations of subject to confine myself to a portion of the material I gathered personally, both while I was with them, and later, when I set out on my visit alone to all the tribes of Arctic North America.

It was my privilege, as one born in Greenland, and speaking the Eskimo language as my native tongue, to know these people in an intimate way. My life's course led inevitably toward Arctic exploration, for my father, a missionary among the Eskimos, married one who was proud of some portion of Eskimo blood. From the very nature of things, I was endowed with attributes for Polar work which outlanders have to acquire through painful experience. My playmates were native Greenlanders; from the earliest boyhood I played and worked with the hunters, so that even the hardships of the most strenuous sledge-trips became pleasant routine for me.

I was eight years old when I drove my own team of dogs, and at ten I had a rifle of my own. No wonder, therefore, that the expeditions of later years were like happy continuations of the experiences of my childhood and youth.

Later, when I became aware of the interest which the culture and history of the Eskimo hold for science, I was able to spend eighteen years in Greenland again, laying down the foundation, by the long study of one tribe, for a more comprehensive study of all the tribes.

In 1902, I began my active ethnographical and geographical work with the Eskimos, which has continued pretty steadily since. In 1910 I established, in collaboration with M. Ib Nyeboe, a station for trading and for study in North Greenland, and to it I gave the name of "Thule," because it was the most northerly post in the world,—literally, the Ultima Thule. This became the base of my subsequent expeditions, four major efforts in ten years, and all called "Thule Expeditions."

By 1920 I had completed my program of work in Greenland, and the time had come to attack the great primary problem of the origin of the Eskimo race. The latter enterprise took definite shape in the summer of 1921, in the organization of an expedition which went from Greenland all the way to the Pacific. At the beginning we worked from a headquarters on Danish Island, west of Baffinland, excavating among the ruins of a former Eskimo civilization, and studying the primitive inland Eskimo of what are known as the Barren Grounds.

Later, with two Eskimo companions, I travelled by dog sledge clear across the continent to the Bering Sea. I visited all the tribes on the way, living on the country, and sharing the life of the people. What I observed on that trip constitutes my story.

The Eskimo is the hero of this book. His history, his present culture, his daily hardships, and his spiritual life constitute the theme and the narrative. Only in form of telling, and as a means of binding together the various incidents is it even a record of my long trip by dog sledge. Whatever is merely personal in my adventures must be cut out, along with the record of the scientific achievements of my associates.

Even the Eskimo will suffer some omissions,—for it is obvious that only a portion of the story can be told, when the selection has to be made from thirty note-books, and 20,000 items of illustrative material.

Yet I think it due my companions, before so summarily disposing of them, to point out that the first year of joint effort with them helped greatly to shape my own work and to spur me to enthusiasm sufficient to carry over the long pull alone. In enumerating the rest of the party, I am in one sense naming co-authors.

With me, then, were Peter Freuchen, cartographer and naturalist; Therkel Mathiassen, archeologist and cartographer; Kaj Birket-Smith, ethnographer and geographer; Helge Bangsted, scientific assistant; Jacob Olsen, assistant and interpreter; and Peder Pedersen, Captain of the Expedition's motor schooner, Sea-King.

The official title of the Expedition was: "The Fifth Thule Expedition,—Danish Ethnographical Expedition to Arctic North America, 1921-24."

It was honored by the patronage of King Christian X. of Denmark, and advised by a committee consisting of M. Ib Nyeboe, chairman, and Chr. Erichssen, Col. J. P. Koch, Professors O. B. Boeggild, Ad Jensen, C. H. Ostenfeld, of Copenhagen University, and Th. Thomsen, Inspector of the National Museum at Copenhagen.

Hardly less important to the comfort and success of the Expedition than the work of these scientists was the contribution of our Eskimo assistants from Greenland, and those we added locally from time to time. We brought with us Iggianguaq and his wife, Anarulunguaq; Arqioq and his wife Anaranguaq; Nasaitordluarsuk, hereinafter known as "Bosun," together with his wife, Aqatsaq; and finally, a young man, known as Miteq,—a cousin of Anarulunguaq.

Anarulunguaq is the first Eskimo woman to travel widely, and along with Miteq, the only one to visit all the tribes of her kinsmen. She has received a medal from the King of Denmark for her fine work. After the first year, I struck out with one team of dogs and these two Eskimos for the trip across to Nome. Considering the rigors they endured, I don't know which is the more remarkable, that I came through the three and a half years with the same team of dogs, or with the same Eskimos. Surely, however, it is no mere sentimental gesture to point out that they had a bigger share in the outcome of the trip than I have space to show.

One omission likely to be welcomed, at least by the reader, is the almost total excision of theories about the origins of the Eskimos. This being one of the chief assignments of our research, I think it a mark of strict literary discipline to have succeeded in keeping it so nearly completely out of the story,—at least in the manner approved by scientists. As an outlet to suppressed dogmatizing, therefore, I am going to make a compact little statement, at this point, of some of our conclusions, and hereafter allow the facts to point to their own conclusions.

The Eskimos are widely scattered from Greenland to Siberia, along the Arctic Circle, about one-third of the way around the globe. They total in all no more than 33,000 souls, which represents, perhaps, the outside number of persons who can gain their livelihood by hunting in a country so forbidding. They have a wide range in following the seasonal movement of game, but in so vast a territory the different tribes are scattered and isolated from each other. Good evidence leads us to believe that a period of at least 1500 years has elapsed since the various tribes broke off from one original stock.

In so prolonged a separation, it would be natural for the language and traditions of the various tribes to have lost all homogeneity. Yet the remarkable thing I found was that my Greenland dialect served to get me into complete understanding with all the tribes. Two great divisions appeared in the customs,—a land culture and a coastal culture. The most primitive Eskimos, a nomadic tribe who lived in the interior and hunted caribou, had almost no knowledge of the sea, and their customs and tabus were limited accordingly. Nothing in their traditions or implements indicated that they had ever been. acquainted with marine pursuits. But the folklore of the sea-people, in addition to being unique in its references to ocean life, was in many other respects identical with that of the tribes that had never been down to sea. The conclusion was inevitable that originally all the Eskimos were land hunters, and that a portion of them later turned to hunting sea-mammals. The latter people retained all their old vocabulary and myths, and added thereto a nomenclature and a folklore growing out of their experience on the water.

As for what happened before that, in the remote past, the theory I came to accept was that long, long ago, the Eskimos and the Indians were of common root. But different conditions developed different customs, to such a degree that now there seems to be no resemblance between the Indians and the Eskimos. But the likenesses are there, not obvious to the wayfarer, but sufficiently plain to the microscopic eye of the scientist.

The aboriginal Eskimos developed a special culture around the big rivers and lakes of the northernmost part of Canada. From here, they moved down to the coast, either because they were driven by hostile tribes or because they had to follow the caribou in their migrations. They developed the first phases of a coastal culture at the Arctic Coast of Canada, most probably between Coronation Gulf and the Magnetic North Pole.

From here they wandered over to Labrador, Baffinland, and Greenland, to the east, and westward, reached Alaska and the Bering Sea. Around the Bering, with its abundance of sea-animals, they had their Golden Age, as a coastal people.

From here a new migration took place, for what reason we cannot know, but this time from the West to the East, and here we find the explanation for all the ruins of permanent winter houses we discovered along the Arctic Coast between Greenland and Alaska. The present Eskimos do not construct such houses, which were built in rather recent times by people known as the Tunit. The Greenlanders, however, do, and they are undoubtedly the original Tunit.

During all these years of migration, some tribes kept to their old places in the interior, which explains why we were able to find aboriginal Eskimos in the Barren Grounds. These facts, together, explain why the spiritual culture exhibited a certain continuity between all the tribes.

The foregoing was the theory advanced by Prof. H. P. Steensby, of the University of Copenhagen, and all of our researches lent support to it.

There is another general theory with regard to the Eskimos which has but slight relation to the question of American origins, for it goes back to much more ancient times,—not less than 25,000 years ago. This theory traces the Eskimo back to a time when our own ancestors of the Glacial Period lived under similar arctic conditions, and, presumably, resembled the Eskimo of today. All remains of the material culture of the Glacial, or Stone Age are exactly comparable with that of the Arctic dwellers, and the theory assumes that a similar spiritual resemblance can be inferred. This grows naturally out of the discovery that the Eskimos, intimately studied, are much more spiritual-minded, much more intelligent, much more likeable than the average man has been led to expect. They prove to be human beings just like ourselves,—so like, indeed, that we cannot avoid drawing them into the fold, and saying, "These people belong to our race!"

For they do, certainly, react to the suffering, the sacrifices, the hardships and the mysteries of evil which they face, much as we do. Their philosophy, even when untouched by any influences of civilization, has many curiously modern slants, including such ideas as auto-suggestion, spirit seances, and cataleptcy. Their poetry has many resemblances to ours, their religion and folklore often resemble, even in phrasing, as well as in content, our earlier religious literature.

Some archeologists have made bold to assert that the Eskimos are surviving remnants of the Stone Age we know, and are, therefore, our contemporary ancestors. We don't have to go so far to claim kinship with them, however, for we recognize them as brothers.

I believe that the following pages will bear out this statement. Even so, I do not dare to feel that the whole story of the Eskimo, or his whole appeal to our sympathies will be found here.

The Expedition started from Copenhagen on the 17th of June, 1921, and proceeded via Greenland, in order to pick up additional members of the party, and arctic equipment. The vessel employed was one built especially for the trip,—the schooner Sea-King, of something over 100 tons.

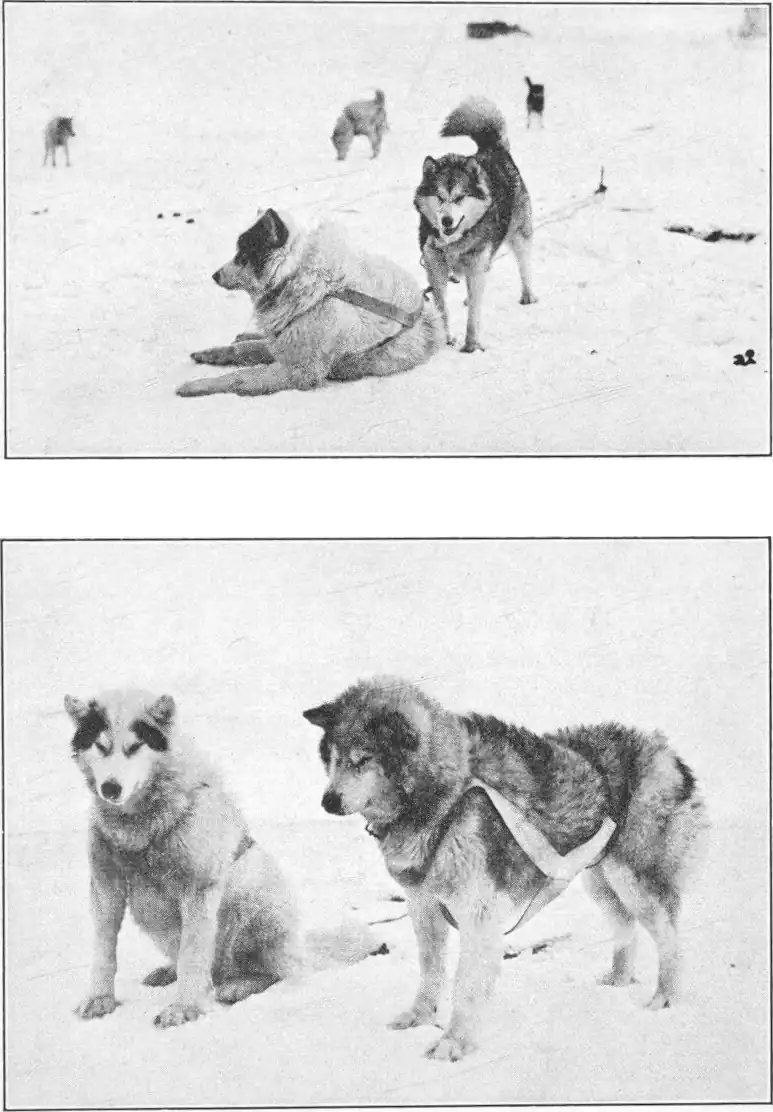

Since the scientific members of the Expedition would be so occupied with their tasks that they would hardly have time for hunting, and procuring food for the dogs, this important task was to be entrusted to the Greenlanders from Thule, who are at once skilful travellers and notable hunters.

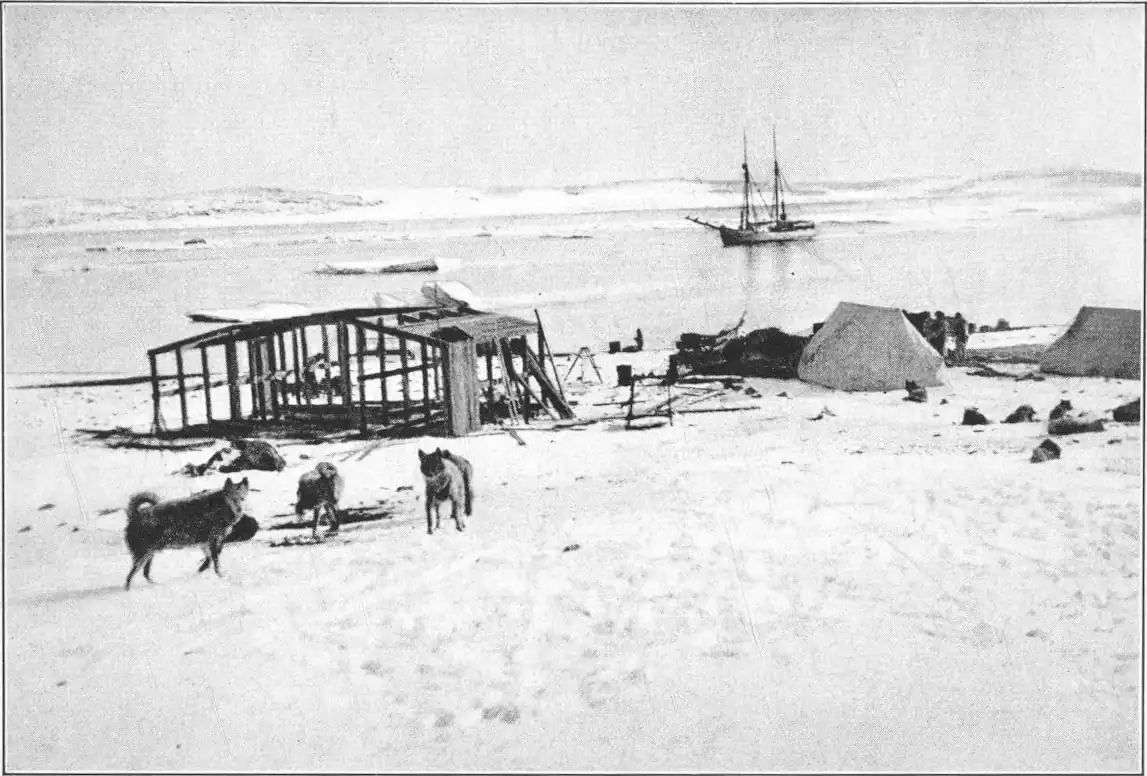

After a favorable passage across the dreaded and ice-filled Melville Bay, we arrived at Thule on the 3rd of August, and engaged our native assistants. Leaving Greenland through Fox Channel in mid-September, forcing a passage through heavy ice around to the north of Southampton Island, we found a harbor on a little, unknown and uninhabited island. A whole month was spent in building a house for our winter quarters,—we called it the "Blow-hole," by reason of the prevalent winds—and in sledge trips in various directions with a view to ascertaining our position. Our observations gave this as 65° 54' N, 85° 50' W, but the old maps were so inadequate that we could not at first mark the locality on any existing chart.

The place was afterward called Danish Island. Here in a smiling valley opening seaward upon a shelving beach, and landward, sheltered by a great crescent of guardian hills, we erected what was to be our home for months to come.

Scarcely were we ashore when we found fresh bear tracks in the sand immediately below the location we had chosen for our home. On our first brief reconnaissance to the top of a neighboring hill, we encountered a hare so amazingly tame that we were tempted actually to essay his capture with our bare hands. Soon afterward we spied a lonely caribou who at once was all curiosity and came running toward us to investigate these strange visitors. The confidence of the game showed well enough how little disturbed the region had been. Never before had I encountered from animals such a friendly greeting.

From the top of the hills we had a fine view of a neighboring fjord, and out in the open water were seen glistening dark backs of walrus curving along the surface as they fed. Such was our first impression of this new country, truly a land hospitable in its promise of game.

By October, the ground was covered with snow, and a narrow channel behind the house frozen over. The first thing now was to get into touch with the nearest natives as soon as possible; but as the mouth of Gore Bay was open water we were unable to travel far, and by the end of October all we had found was a few old cairns and rough stone shelters built by the Eskimo of earlier days for the purpose of caribou hunting with bow and arrow. The first meeting with the Eskimos of the new world was yet before us.