Greenland by the Polar Sea/Appendix 1

APPENDICES

FLORA AND FAUNA ON THE NORTH COAST OF GREENLAND

BASED ON DR. WULFF'S NOTES

By C. H. OSTENFELD

PAGE after page of Thorild Wulff's diaries testify to the fact that his thoughts occupied themselves greatly with the problem: How is it possible for plants and animals to live and reproduce themselves under such harsh conditions of life as the high Arctic regions offer, and what peculiarities are they which enable them to do so?

The problem is not a new one. On the contrary, it has forced itself upon every Arctic explorer who keenly observes the natural characteristics of the regions through which he travels. In the course of time numerous contributions have appeared with regard to this problem, but many aspects are still unsolved. Neither do Wulff's notes present a final and exhaustive reply, but they contain several new observations and conclusions, thus forming new stones to be added to the many-roomed building of our knowledge.

In the Arctic countries, as everywhere else upon earth, the flora forms the foundation for the fauna. Where no plant exists, no animal life is possible, for all creation of organic matter is due to plants. The animals, on the other hand, are merely consumers. If they are herbivorous they consume directly vegetable matter, and if they are carnivorous they consume the flesh of herbivorous animals. In both cases we find as the last instance the plants as the bearers of life.

When we consider the flora and fauna of the north coast of Greenland, it would therefore seem natural that we should commence by an examination of the flora, investigating the conditions of life with which they must contend. The climatic conditions are anything but favourable, and only the hardiest plants with the most modest requirements can exist in these regions; therefore the number of plant varieties is only small—about sixty flowering plants—and they all bear a certain common stamp.

In order to thrive a plant requires: Nourishment from the soil, a certain amount of heat and moisture, and light. The first condition is fulfilled almost everywhere in the Arctic regions, so poor in plant life, by the presence of nutritive salts. The soil produced by disintegration (frost, etc.) is as a rule more than sufficient for this purpose, as the plants do not grow so closely that they have to fight with each other for the nourishment in the ground. This claim of life we may thus put aside, but it is worth noticing that vegetation is richer where the ground consists of certain kinds of rock—for instance. limestone, than of others—for instance, ground rock. This, however, is no peculiarity confined to the Arctic regions.

The second condition of life—heat—is in the Arctic regions present to such a small degree that it becomes of definite significance to the luxuriance of plant growth. We will therefore examine this point more closely, deciding from the outset that plants cannot grow at temperatures below freezing-point. On the other hand, Arctic plants can put up with being frozen stiff without detrimental effects. Their growth stops, but as soon as they thaw they recommence their growth. Thus Wulff observed (on the 4th of May) a tuftsaxifrage with fully developed flowers on inch-long stalks; it was quite frozen, the temperature of the air being minus 11° C., but all tissues seemed capable of life, and when spring returned it would, without doubt, directly continue its development.

On the north coast of Greenland the temperature is above freezing-point only during a short period of the year. At noon on the 30th of May the first positive temperature of the air was observed (plus 0 8° C.), and by the end of August the continual frost again sets in. There is thus only a period of at most three months within which the plants have to grow, flower, and fruit, and store nourishment for next year. And how many hours, or even days, within this short time must be subtracted because snow and cold stop the growth! In the middle of June Wulff wrote in his diary (17th of June): The vegetation is yet in its winter repose. The soil is frozen; the plants which I brought from our previous camp cannot yet be pressed, as the clumps of moss and pieces of soil attached to them are frozen rigid." He is of the opinion that, on the whole, vegetation revives only by the summer solstice, and writes very aptly: The explosive' development of the Arctic vegetation takes place in a kind of staccato—rapidly during the warm, light hours, and ceases entirely during the many long, cold, windy days of sleet."

One would think it impossible for plants to manage with so little warmth, but it is sufficient for the most frugal among them. It is a help to them that the soil and the plants themselves are warmed more quickly and to a higher degree than the surrounding air. It is a well-known phenomenon that a dark surface subjected to the rays of the sun becomes warmer than the air; and in Arctic regions this fact is undoubtedly of great importance for the growth of the plants.

Similarly to other Arctic explorers, Wulff has repeatedly measured the temperature on various types of ground in order to obtain statistics to illustrate this point. A few of his results will be given here to demonstrate the various differences:

May 19th, 2 p.m.—A hill sloping towards the sun. Calm, clear sunshine (McMillan Valley).

Temperature of the air in the shade minus 11.8° C.

The thermometer with its ball of mercury:

- On a light-brown, sunny cliff of sandstone: minus 1° C.

- On a sunny clump of saxifrage: plus 28° C.

- In cespitous moss: plus 9.2° C.

June 20th, 4 p.m.—A slope to the west. Calm, clear sunshine (Chip Inlet).

Temperature of the air in the shade plus 5° C.

The thermometer with its ball of mercury:

- On a sunny, flowering tuft of saxifrage: plus 21'1° C.

- 2 cms. down in dry, sandy soil: plus 14'2° C.

- 6 cms. down in moist, sandy soil: plus 12'5° C.

- 12 cms. down in moist, sandy soil: plus 7'3° C.

July 15th, 1 a.m.—A slope 100 metres above sea-level. Plentiful vegetation. Calm, clear sunshine (Summer Valley).

Temperature of the air in the shade plus 12° C.

The thermometer with its ball of mercury:

- On a sunny cluster of poppies: plus 24'4° C.

- 3 cms. down in a vigorous green clump of silene: plus 24'3° C.

- 10 cms. down in the same clump (near its bottom): plus 11'8° C.

- 1 cm. down in moist soil: plus 18'5° C.

- 13 cms. down in moist soil: plus 14'8° C.

These examples show quite plainly that the plants, fortunately for them, get considerably more heat than one might expect, judging from the temperature of the air alone. But one must not overestimate the significance of these figures, as they hold good only when the air is calm. The wind naturally cools considerably the surface of the soil and the vegetation, so that on a windy day there will be no appreciable difference between the temperatures of the air and the soil. Further, sun is necessary, so that again on dull days conditions will be different. Thus the limitations must not be underestimated, though it is of importance to note that a sunny slope, well sheltered, always exhibits the most vigorous and the earliest development of vegetation.

In Arctic regions, where snow and ice abound, one would expect there to be always sufficient moisture for the plants; but this is not the case under all circumstances. The ability of the plants to absorb water is relative to the degree of warmth. Below zero the roots of the plants naturally are unable to absorb water; but also at low positive temperatures the absorption of water takes place very slowly. Thus a disproportion between absorption and evaporation from the parts above ground might easily arise when the latter are exposed to strong sunshine. In this comparison one must remember that the soil in the high Arctic countries is permanently frozen at a certain depth; the summer heat is able to thaw merely the upper layers. To satisfy their need of water the plants are thus restricted to the absorption of moisture from this layer, and from the water liberated by the melting of the snow. There may, of course, be cases where this is insufficient, or where, at any rate, water can merely be absorbed to so slight a degree that only certain varieties of plants can manage. Because of the evaporation due to very dry air and strong sunshine, the soil, which first is laid bare when the snow evaporates, often becomes very dry, as the frozen subsoil only to a slight degree permits the water to rise to the surface. Wulff's diary contained many notes about this; for instance, on the 9th of June he wrote: "The snow is melting rapidly, but the water evaporates quickly, so that it does not moisten the soil at all except round the patches of snow"; and not until the 15th of June did he notice that the melting took place to such a degree that the water could run along the ground. He therefore thought it probable that, under conditions like these, the plant roots must be able to absorb the water which presumably rises from the frozen subsoil because of the capillary action between the particles of the dry upper layers. Not until the 10th of July does he write in his diary: Mild, quiet rain falls for several hours, the first proper rain this year." Thus there is a period—the springtime of vegetation in these latitudes—during which the plants may be exposed to thirst, a fact which one might refuse to believe if one thought merely of the omnipresent enormous masses of snow and ice. Later on there will be more than sufficient water; the snow melts so that the soil becomes slushy, and snow and rain fall in abundance; then the plants have some difficulty in not getting drowned.

If the Arctic plants are thus subjected to pronounced extremes with regard. to moisture, the peculiarities do not become less when we consider their relation to the light. To thrive, every green plant requires light, as light is one of the essential conditions for the formation of organic matter from the carbonic acid of the air. In the Far North the winter is a dark period when the plants sleep under their cover of snow, but, as a compensation, during summer there is light both day and night. As far as the light is concerned, the plants are thus able to work and build through the whole of the twenty-four hours, so that the short duration of summer is to some degree counterbalanced. This has been demonstrated by experiments; they really are capable of exploiting this advantage which they have over their kindred of more southern regions, where the darkness interrupts their work.

Summing up these considerations, one may say that high Arctic plants have a much shorter time of vegetation—merely two or three of the twelve months of the year—but that, on the other hand, during this period they have to work incessantly under difficult and harsh conditions.

We shall now see what the plants that are to be found in these regions look like, and how they are adapted to their conditions.

The most prominent feature of the high Arctic plants is the fact that they are low and keep close to the ground. They are mostly herbaceous, though some are low shrubs. Shrubs as we know them, not to mention trees, do not exist so far north.

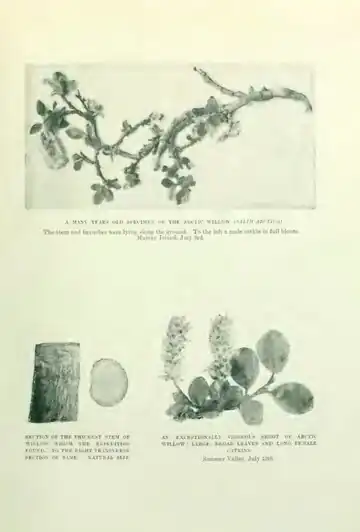

The largest plant is the Arctic willow. Old specimens of this may, even on the north coast of Greenland, have a stem rather thicker than a finger and more than a metre long; but it lies along the ground, forming by its profuse branching a network through which the leaves and catkins of the year peep out. Similarly to other varieties of willow, it sheds its leaves in the autumn. Another dwarf bush characterizing the high Arctic regions is the Arctic heather, whose tiny evergreen leaves, packed closely together, form four rows along the branches, thereby giving them a square shape; it has beautiful, white, bell-shaped flowers, much resembling the lily of the valley. The whole of the bush is rich in fragrant resinous matter, which makes it excellent fuel.

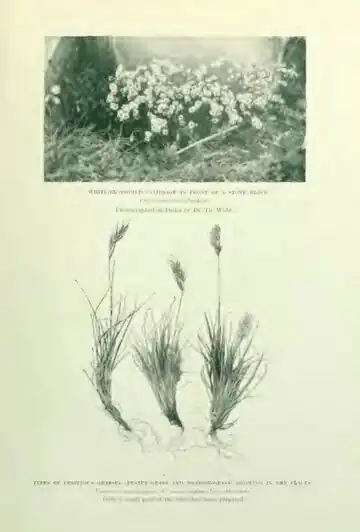

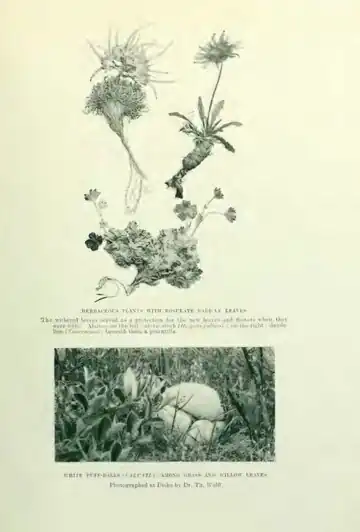

Two very common dwarf bushes are the red saxifrage and the white mountain anemone; both have rather thick leaves which, as a rule, wither in the course of the winter, but remain on the plant as a protection for the young leaves and buds.

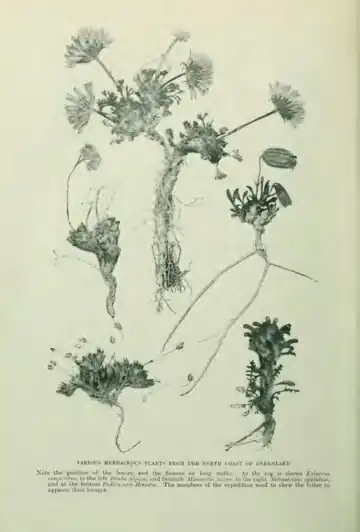

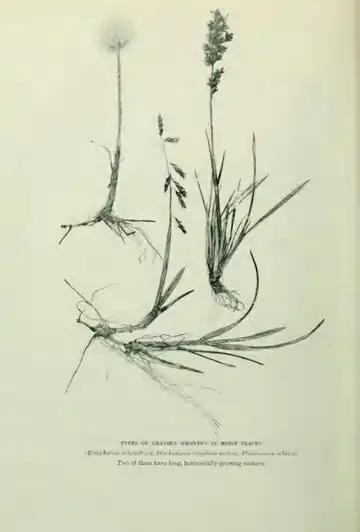

Many of the herbaceous plants form small, close clumps where the shoots fight for room; every shoot has a few fresh green leaves towards the top, whilst the rest is hidden in a thick bed of withered leaves. The flowers shoot up above the surface of the clump. This cespitous formation may be observed in the tuft-saxifrage, in the tuft-silene (where the clumps may be so strongly arched that they almost assume a half-ball shape), in the little white or yellow draba, and in many others, as, for instance, several varieties of grasses.

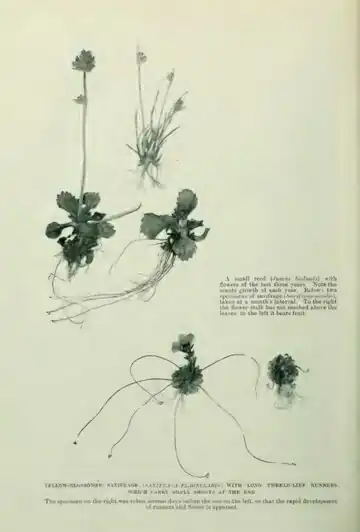

Other herbaceous plants may have leaves clustering close to the ground, and flowers freely raised on shorter or longer stalks, but the shoots are not so close as in the cespitous plants proper. To these belong, for instance, the beautiful yellow or white mountain poppy and several varieties of saxifrage and potentilla.

In moist soil, in swamps and similar places, grow cotton grass, a few varieties of other grasses, and some other plants; for instance, the yellow crowfoot. In these varieties the shoots are spread out and stand singly, as do plants in swamps and fens in this country.

All these plants are perennial; annual varieties do not exist so far north. It is not possible for a flower to sprout, grow, flower, and fruit during the short summer; the work has to be distributed over several years, as one single year would merely give time for a slight production of organic matter. Every shoot forms merely a small piece of stalk and a few leaves, so that several years will elapse before the plant is strong enough to develop flower and fruit.

From the plants of our own country we know that a considerable period generally elapses between flowering and the ripening of the fruit, and as a rule the flowering takes place some time after the leaves have commenced their development in the spring. An Arctic plant has not all this time at its disposal, having to flower and fruit during a period of vegetation of two to three months. In most Arctic plants the flowering therefore takes place immediately after the development has commenced in the "spring." The red saxifrage is the first vernal flower of the high north. Wulff saw it flowering already on the 12th of June, this being a time when vegetation in many other places had not awakened from its winter rest. But after that things developed rapidly. About two or three weeks after the vegetation as a whole had begun to move, most of the varieties were already in full flower (July 7th to 14th), and by the beginning of August (2nd) the red saxifrage, mountain anemone, and others, were already in an advanced stage of fruition." The summer was nearly over, and when the expedition after the march across the inland-ice once more came down on ice-free land on the 24th of August, it found the vegetation in its full autumnal garb, with ripe seeds and yellow and russet leaves.

Thus the plants have a busy time, and they are only enabled to carry out their programme by considering carefully the hours, and by being prepared to set to as soon as spring comes. If one were to examine an Arctic plant immediately before it goes to its winter rest, one would be surprised to see how big are the buds of next year. If the outer protecting husks of such a bud are removed, one will find inside these both leaves and flowers already far developed. They remain in this state throughout the winter, their living tissues, as already mentioned, being able to resist very strong cold; and as soon as spring beckons they burst out. By this the speedy flowering is made possible, and this, again, gives sufficient time for the ripening of the fruit just at the time when the temperature is at its highest.

The plants which flower earlier are those which become uncovered soonest when the snow in the spring begins to evaporate, and those which have been uncovered by snow through the winter. These are the most hardy varieties. The more delicate—if one may use the word "delicate" in connection with the hardy vegetation of the high North—are covered with snow during winter, and only emerge from its protective cover when the melting of the snow commences in earnest. For the snow plays an important part in plant life, as it prevents too sudden changes in temperature, and also protects them against a too vigorous drying-up by the wind. Many varieties were only discovered by Wulff during the month of July, as they had been hidden by the snow until then. In his diaries he repeatedly expresses his surprise at finding that first one and then another of the varieties are missing; but later on the error is corrected: "It is here after all, but it was covered by the snow."

As already mentioned, all the various species are perennial, this being in accordance with the short period of vegetation. Yet another fact must be mentioned in this connection: several Arctic plants do not get time for a yearly ripening of their fruit. This may be due to an unusually early arrival of autumn, with frost, or to a late spring, so that the plants become bare of snow very late. Under these circumstances annual plants would soon have to give up; but the perennial plants, on the other hand, can wait for a favourable There are Arctic plants which only occasionally reach the state of fruition, being limited during other years to a mere state of vegetation.

The Arctic flowers have often been praised for their size and their clear colours, and considering their hard conditions of life one cannot help wondering that so much beauty can be developed; but nevertheless they are very modest in comparison with the flowers of our homely plants. It is the desolate surroundings which make the Arctic flowers so conspicuous.

The pollination of the flowers and the subsequent fertilization is, of course, the prelude to fructification. Pollination takes place either by the aid of the wind, the pollen being carried along through the air, when it is a matter of chance whether or no it will alight on a flower, or by the aid of the insects; thus it is also in high Arctic countries. In the short summer, flies, humblebees and multi-coloured butterflies flit from flower to flower in search of honey and pollen, and these simultaneously undertake the pollination. The more open flowers, like the poppy and the anemone, attract the flies, whilst the butterflies lower their long probosces into the nectary of the silene, the red saxifrage, and the Arctic stock or night-smelling rocket, a rare plant found in several places on the north coast of Greenland. This latter possesses a strong odour, a very uncommon quality among Arctic plants. White or yellow are the most frequent colours of flowers, but red in various shades is also to be found; blue, on the contrary, is very rare in the Arctic regions, and no flower found on the north coast of Greenland is of this colour.

So far we have only considered the flowering plants; but besides these a considerable number of mosses and lichens exist. The lichens grow especially on the naked rock, which in many places they adorn with their vivid white, yellow, and reddish colours, whilst the mosses mostly grow on the soil among the flowering plants.

Also a few fungi are to be found on the north coast. Wulff mentions small yellowish-brown toadstools and white puff-balls. The latter are edible; he mentions a really good dish made from the product of the land: musk-ox soup with brent-goose bones and a couple of handfuls of chopped puff-balls.

I shall not go deeply into the matter of the way in which the various plants combine into a plant society. I will merely mention that vegetation is not evenly distributed. For the most part the soil is almost bare, with single or scattered plants; but in the more fertile places—for instance, where the excrements of the animals have fertilized the soil—the plants occasionally form an entirely connected cover; but these spots are not extensive. In the bogs one also occasionally meets with a rather dense growth of plants, mostly mosses and grass.

A distribution of plants peculiar to high Arctic regions is the so-called "chequer-ground." When the snow melts, the loose, flat ground will in several places turn to a porridge of sodden sand and clay. When this porridge freezes or is dried up, cracks will, according to physical laws, be formed in it, so that it becomes, as it were, divided up into a lot of many-sided little spaces framed in the network of the cracks. This structure may keep its form for years, and in this case the cracks will become deeper. When the plants invade this ground they generally settle in the cracks, the seeds being blown there by the wind, the plants finding there the necessary shelter. In this way the network of the cracks becomes covered with plants, whilst the "chequers" themselves remain bare. This chequer-ground is, according to Wulff's diaries, very common on the north coast of Greenland.

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

When we consider how scanty is the vegetation, it is really surprising that animal life on the north coast of Greenland is so rich, and especially that so many large animals are to be found. Much has been told of these animals in Knud Rasmussen's narrative, as they were of vital importance to the expedition.

If we keep to the land animals and consider especially the larger of them—i.e., mammals and birds—it would seem natural to divide them into herbivorous and carnivorous animals.

Among the herbivorous the musk-ox is the foremost. The expedition depended chiefly upon this animal for its food, and it was mainly due to the fact that musk-ox was found only occasionally on the north coast, and in a considerable number only in one place (in one fjord), that men and dogs suffered so much from hunger. Why the musk-ox preferred this one place we do not know. The vegetation was no more vigorous in the musk-ox fjord than in other places; but in the whole district it was so sparse that probably the limit of what a musk-ox can be content with had been reached. This is indicated by the fact that the expedition did not meet with any calves.

Wulff examined several stomachs of musk-oxen, and always found them filled with twigs of willow and, to a less degree, with leaves of anemone and other plants.

Two herbivorous mammals which were very numerous were the Arctic hare and the little Arctic lemming. The former of these played an important part as food for the expedition; the latter is so small—its size is between that of a mouse and a rat—that it has no significance as food for men and dogs. The fully grown Arctic hare is white all the year round, with merely a slight dark shade on the head; but the young which were observed in the beginning of July were greyish-brown. The hare was common everywhere, and lived on various plants; according to the observations made by the Danmark Expedition on the east coast of Greenland, it was especially fond of the roots of the Arctic willow, which it dug up with its forepaws and snout.

The little greyish-brown lemming is a very timid and nervous animal, which chiefly keeps to its subterranean den, where it hibernates during the winter. In some places, especially where vegetation was vigorous, it existed in great numbers, though it was not often seen, because of its timidity. It would occasionally set out on a long journey; thus, for instance, it was met with a few times out on the fjord-ice. Wulff relates a very funny experience on the 23rd of June: "Several kilometres out on the fjord-ice I met a small lemming, quickly trotting along across the immense white field of snow. As I did not feel disposed to go far out of my way for the sake of the little mite, I whistled, with the result that the lemming stopped at once. Every time it recommenced its rolling along, like a fluffy little ball of wool, I whistled and made it stop. When I came stamping up to it on my large snowshoes, the Lilliputian sat up on its hind legs, spat at me, and showed its teeth. The little wanderer ended its days by a slight knock across the snout."

Of the birds, the ptarmigan is most common. The expedition met with it wherever it went. In the beginning it was white, but, as summer advanced, first the ptarmigan hen and later on the cock became speckled with brown. It subsisted on parts of plants; Wulff found, for instance, many buds of the red saxifrage in its crop. Evidently the ptarmigan here in the north live in couples—not in polygamy, as they do further south—and from approximately the middle of June nests with eggs were found. Young were seen in the latter part of July.

The other herbivorous birds which the expedition saw on the north coast of Greenland were migratory. First the snow-bunting appeared; as early as the 24th of April it was heard twittering when the expedition was on its way to the north coast (N. Lat. 81°). The others came later on. The swimmers were: The brent-goose, the king-eider, and the long-tailed duck; of these only the brent-goose was common; it was seen for the first time on the 11th of June—that is, during the first days of spring.

As a link between the swimming birds and the carnivorous animals we may put down the waders, which live on small animals in the pools, and are also truly grateful for the half-rotted and floating parts of plants amongst which the little animals are found. Of these the most common were the sandpipers and the turnstones. The sandpipers arrived first, being seen as early as the 30th of May, whilst the turnstone was not observed until the 10th of June. About the 1st of July the first eggs of these birds were found, and on the 20th their young were seen.

Terns and gulls are carnivorous. They were not observed very frequently. The tern was seen in the middle of June, the gulls (herring-gulls and ivory-gulls) both before and after this date. Very common was the little Arctic gull with its elegant bifurcate tail and its long wings; it arrived on the 9th of June, and its young appeared just after the middle of July. It is a proper beast of prey whose food mainly consists, to judge from the contents of its stomach, of the little lemming; this agrees with the observations of the Danmark Expedition.

But the worst robber amongst the birds in these regions is the snowy owl, which was seen occasionally, and the nest of which was also found. Neither the raven nor the Icelandic falcon were observed on the north coast of Greenland; but no doubt both birds would occasionally pass these districts on their long flights.

The carnivorous mammals are generally observed singly or a few together; there is not sufficient food for them to congregate in great numbers. The members of the expedition often saw the white Polar wolf slinking about at a safe distance like an uncomfortable reminder. Also the Polar fox and the ermine are occasionally observed. The Polar bear seems to be very rare on the north coast; only at rare intervals were its tracks found, and a newly killed young seal by Dragon Point was assumed to have fallen a victim to it.

As the sea off the coast and in the fjords is permanently frozen, one cannot expect to find many marine animals. There were, however, several seals frequenting the lanes along the coast. As Knud Rasmussen has told us, they were eagerly hunted by the expedition, as a rule, unfortunately, without success, as the shot animals sank down into the fresh water; the freshness of the water is due partly to the afflux of water from land, partly to the melting ice.

Their food consisted of sea-scorpions, halibuts, Polar cod, and various animals from the bottom of the sea.

On the north coast of Greenland, contrary to other Arctic regions, bird-cliffs seemed to be entirely lacking. Consequently none of the various auks were observed, and the fulmar, which also breeds on the bird-cliffs, was seen only once; the three-toed gull was not seen at all.

Of lower animals the insects are specially noticeable. Wulff has many notes about them. Flies and gnats were most numerous, but as we have already mentioned under the fertilization of flowers, humblebees and butterflies were also found. Unfortunately, one knows very little about the wintering of these insects; some of them evidently winter as fully grown insects, others as pupa and larvæ, and others probably as eggs. It is remarkable that a fully grown insect or a larva is able to resist the long and terribly cold winter.

On the 30th of May—the first day of a positive temperature by noon—Wulff for the first time saw gnats; evidently they had hibernated through the winter, and then been revived by the warm rays of the spring sun.

Half a score of days later (9th of June) he observed big flies playing and mating on the canvas of the tent. They had probably wintered as pupa. Their eggs were subsequently found (25th of June) in great numbers on the musk-ox skins.

A large, woolly, yellowish-brown larva of a butterfly was observed by Wulff walking in the snow between the twigs of the Arctic willow as early as the 3rd of June, and again on the 9th of June. He then wrote in his diary: "Does it winter as a larva? I am sure it does, for there is nothing for it to eat; also, it is already full-grown."

A month later (13th of July) fully developed butterflies are seen on the flowers—reddish-brown mother-of-pearl butterflies. Somewhat earlier (22nd of June) the humblebees appeared.

Spiders and earth-mites also support life in these high latitudes; and we must not forget that even here the larger animals are not free of parasites: lice and intestinal worms worry the mammals, and the birds have their louse-flies.

Thus quite a series of animals exist even under the harsh and poor conditions of the Polar countries. Their organization and mode of life are each in their own way adapted to their surroundings. Birds and mammals have their animal heat and their thick cover of feathers or hairs wherewith to resist the cold; most of the birds, however, migrate to the south during the coldest period.

Most of the mammals and those of the birds which, like the ptarmigan and the snowy owl, remain in the Arctic regions, are white in winter or all the year round, evidently a protective likeness to the surrounding snow-fields.

The lower animals would appear to be adapted to the Arctic conditions to a far smaller degree; they are unable to withdraw during the unfavourable period as do the migratory birds, and they remain hibernating through the winter. Their power of resistance must be due to internal causes. movable and frozen rigid, they await their waking up to a brief aerial life in the light Arctic summer.