Greenland by the Polar Sea/Appendix 2

GEOLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS

By LAUGE KOCH

THE districts through which the expedition travelled were, from a geological point of view, practically unknown; but as numerous fossils had been found in Ellesmere Land, which was not far distant, there was reason to expect interesting work for the geologist in North-West Greenland.

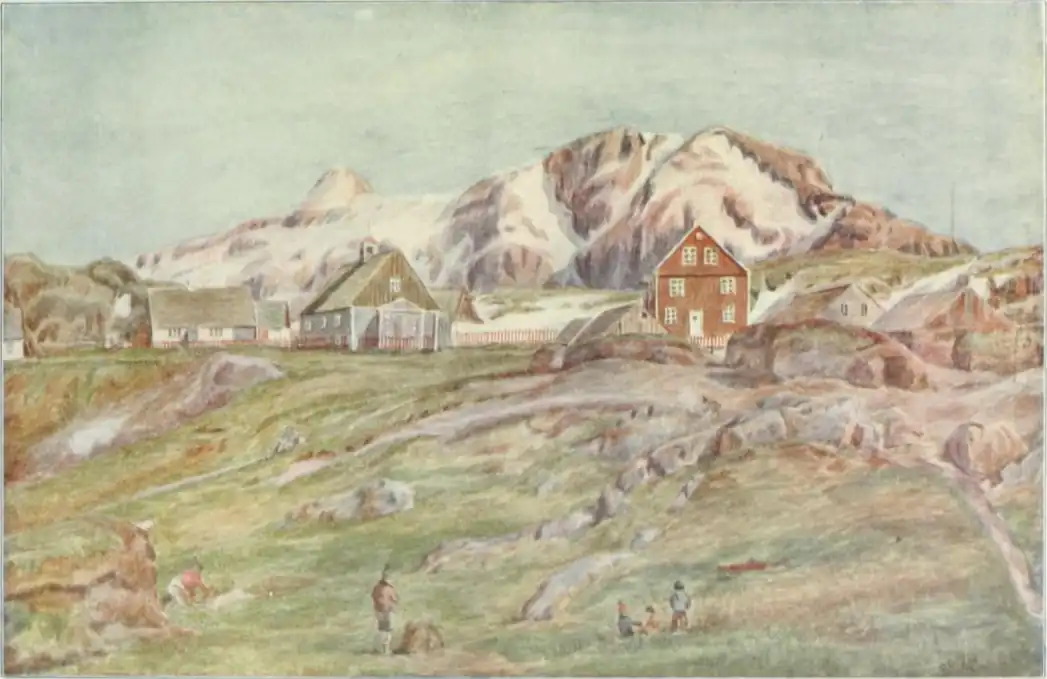

Almost everywhere in Greenland one finds that the coast—similarly to the Norwegian and Swedish "Skjærgaard"[1]—consists of gneiss. This was also the case in the southern part of the districts we surveyed right up to Cape York. The regions to the south of Cape York in Melville Bay clearly illustrate what, for instance, Norway must have looked like in the Ice Period; only the outmost skerries and islets are free, whilst the entire coast is covered by enormous glaciers, the crevassed surface of which is only occasionally broken by steep mountain-tops which push through the ice as nunataks. To the north of Cape York the land is less glaciated. The edge of the inland-ice lies some distance into the country, and only through the larger valleys do glaciers push down to the coast. Thereby the whole landscape changes in character, and this change is further emphasized by the fact that the coast consists of quite other kinds of rock. The gneiss which was found south of Cape York is observed also in several places right up to Humboldt's Glacier, but as a rule it is in this neighbourhood covered by sand and limestone, which form plateaux with steep cliffs out towards the coast.

Even at a distance these coastal mountains give to the landscape a peculiar beauty. One sees at once that they must have been deposited in the ocean, for they are very regularly stratified. The single strata vary in colours, some are almost white, others are yellowish-grey, pink or brown, and through all these strata one sees in many places black veins of diabase. The diabase once burst through the layers as glowing lava, or forced its way between them, and now lies as a protective cover above the lower layers. This fact is plainly visible at Thule, where the upper stratum of the so-called "Camp Mountain consists of a diabasic cover, which has protected the underlying sand and limestone.

If one examines these layers more closely, one finds at once that they must have been deposited in shallow water. In several places the lowest layers of sandstone are seen right above the gneiss. They then form a conglomerate with greater and smaller fragments of the underlying gneiss. These blocks are, as a rule, beautifully rolled and polished, like pebbles. Thus the lower layers are pure beach formations; but also the superincumbent sandstone is deposited in shallow water, for many of the strata are beautifully furrowed. by the beat of the waves, as we see it nowadays on a good bathing beach.

Being deposited on it, these layers of sandstone are, of course, younger than the gneiss. No fossils have been found in them, and it is therefore difficult to decide their age; one may, however, state with certainty that they are older than almost the whole—probably dating from the very earliest part of the Silurian Period.

If one travels northward past the mighty Humboldt's Glacier to Washington. Land, the landscape again changes entirely in character. Here also the cliffs are steep and stratified, but they stand like a vertical wall along the entire coast, and only at a good distance from the coast can one see the inland-ice in the background above the mountains.

These districts which, looked upon as a landscape, are so monotonous, prove on closer examination to be among the most interesting in all North Greenland.

Wherever one lands under the steep mountains one finds stones full of fossils. These fossiliferous strata are found not only on Washington Land, but they also form a broad belt of plateaux right up to Peary Land. It therefore seems natural in considering these formations to take them as a whole. This chain of plateaux mountains, which have a height of upwards of 1,500 metres, forms the border of the inland-ice to the north. Only occasional narrow valleys cut in between the plateaux, and through these long, almost horizontal, glaciers stretch down until they reach the sea.

Examining the fossils more closely, one will soon discover that the rocks may be divided in several strata, every stratum having its characteristic fossils. One will further find that these strata alternate in a definite succession everywhere in the north-west of Greenland.

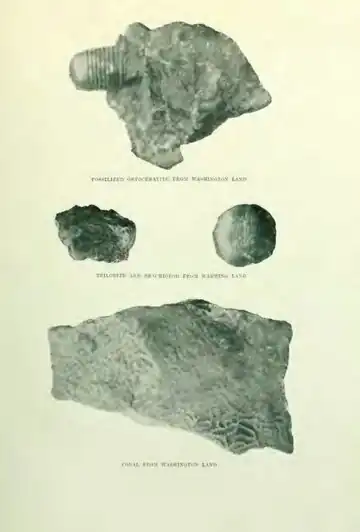

The oldest layers are found in the southern part of Washington Land and in a narrow belt on Warming Land right in against the inland-ice. The barren plain which we called the Midgard-Snake consists of these types of rock. In this place the layers are superincumbent on sandstone with diabase. They are of dark brown limestone with sparse remains of large octopus; the so-called orthoceratites, consisting of long tubes divided into compartments, sometimes straight and sometimes spiral-formed. One sees the same animal forms in flagstones and stair-stones.

On the dark brown limestone lies a mighty series of grey and reddish lime. It is mainly these layers which form the great barrier against the northern push of the inland-ice. At a distance the mountains look extraordinarily monumental; as a rule they have almost vertical walls which, especially when the sun is shining on them, take on a beautiful rust-red colour. Their tops are flat, and in many places they are covered by a level ice-cap. Very peculiar are the deep cloughs and canyons winding their way between the plateaux. Whether these cloughs are formed by glaciers during the Ice Period is rather doubtful; it would seem more probable that they were present, at any rate partly, before the Ice Period. One of these canyons, the Devil's Cleft, we passed on our way towards the inland-ice, where we found excellent opportunity to examine closely the red limestone through which the clough has cut its way down.

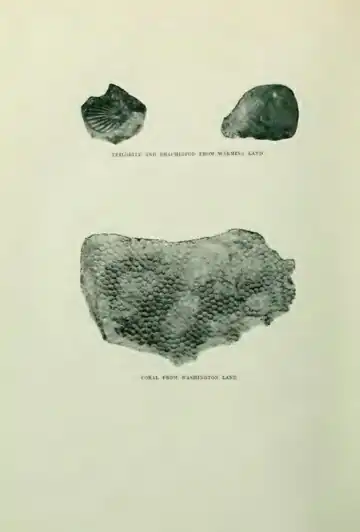

One may walk for a long time without discovering fossils, and we may say that these strata are, on the whole, poor in animal remains; but suddenly one comes across a layer so rich in fossils that they literally make up the entire layer. They consist almost solely of large thick-shelled brachiopods. We found such a layer in the Devil's Cleft; at one time this must have been a place situated at the bottom of the ocean where animal life has been as rich as on an oyster-bed. Now the limestone is absolutely barren, no plant can find nourishment in its cracks, no sign of animal life was to be discovered, and one finds oneself wondering why the inland-ice, which from both sides sends its glaciers right to the edge, does not fling down its masses of ice, filling up the clough.

When these layers were formed there must have been variable conditions at the bottom of the sea. The orthoceratites did not live here whilst the red limestone was deposited, and only in occasional places did favourable conditions for animal life exist; but this animal life was then very rich, though it soon died out again and was covered by a stratum void of fossils.

The upper layers of this limestone, however, point to somewhat different conditions. Between the brachiopods occasional corals are found, becoming increasingly numerous upwards at the same time as the large, thick-shelled brachiopods become rarer; ultimately one sees no more of them, the rock becomes bluish-grey, and the corals dominate.

The succeeding layers are remarkable for their great wealth of animal life. They are especially easy to find in Washington Land. Now one stands on almost a coral reef, now the many-armed crinoidea put their stamp on the stones, and in between the branches of the corals lie remains of innumerable other organisms. The crustacea are represented by trilobites, by octopus, by orthoceratites; further, there are brachiopods, mussels, snails, bryozoa, and fungi. The corals are present in many varieties; some are cup-formed, others are sausage-shaped or ball-shaped, others, again, are flat or look like a plate.

But the period of the corals also comes to an end. The bluish-grey layers with the beautiful branches of coral suddenly stop, and are succeeded by black strata of schist, in which at the first glance no animal remains can be seen; these layers look very much like slate-stone. But if one examines them closely one will find some peculiar shapes which look as if they had been traced on the slate with varnish. Now they are small, saw-toothed sticks, now they are rolled up and have long radiate beams on the outer side; they are the so-called graptolites, an animal group long ago extinct, which does not appear to have any near kindred amongst now existing animal forms.

The black schists are very thin; towards the top they become richer in lime and at the same time the trilobites again appear; but they are chiefly of forms different to those in the coral limestone, and the same holds good for the brachiopods and the orthoceratites. They are mainly small, but of many varieties, and it is as if animal life for the last time flares up before it disappears. If one follows the succession of layers upwards, the slaty limestone rather abruptly becomes mixed with sand, and then merges into pure coarse sandstone without fossils.

This sandstone crumbles easily, wherefore landscapes consisting of this stone appear in the shape of low plains with rounded forms. A whole series of low districts are therefore to be found to the north of the large fossiliferous plateaux right from Hall Basin and almost to Peary Land.

With this the North Greenlandic series is finished. All the fossiliferous strata belong to the Silurian Period. The coarse sandstone shows that the sea again becomes shallow, and one gets the explanation of this if one turns towards the north, where the plains are bordered by an enormous mountain chain.

All the layers deposited in the sea, right from the red sandstone, the dark brown and the reddish-grey limestone, to the coral lime, the black schist, the slaty limestone, and finally the sandstone, appeared as almost horizontal strata, which sloped only faintly towards the north-west. No violent catastrophes of nature have, in the course of time, altered their original stratification; they lie to this day as they were formed on the bottom of the ocean in olden times. Therefore the landscapes in these regions are very monotonous. The colour and the height of the rocks may vary, but the steep coastal mountains, which at their tops form flat plateaux, are a feature repeated again and again in these regions.

If one turns one's eyes to the north, towards the mountain chain, one sees even at a distance that the landscape is quite a different one. The plateaux are succeeded by a wild Alpine country. The flat glaciers, which in appearance resemble the inland-ice, have disappeared, and the country is almost free of ice; only occasionally is a quite small glacier hidden away in some narrow valley.

A glance at the map shows that all the north coast of Greenland is formed by this mountain chain. It runs, however, not at all as a continuous ridge along the coast. In reality there are many ridges between which valleys and fjords cut in; further, the mountains are penetrated again and again by fjords and sounds, so that now only the remains are left of a once much more enormous mountain chain. Especially in the fjords, which cut across the line of mountains, there is a good opportunity to examine what the inside of a mountain chain like this looks like. The inland-ice, which during the Ice Period sent its glaciers out through these fjords, has polished the coastal mountains, which now stand without vegetation as long profiles in which one can see exceedingly clearly how the strata lie.

One sees at once that the mountain chain has arisen by the layers, which were once horizontal, being pushed up into enormous folds by pressure from the sides. In the southern part of the mountain chain one can see how the coarse sandstone, which on the plains lies horizontally, gradually assumes a more wavelike surface, finally merging into the great folds of the central section of the mountain chain. Upon closer examination one will probably also find the fossiliferous layers pressed up, as these must be assumed to stretch out beneath the sandstone under the surface of the sea. These pressed and folded strata have been subjected to such an enormous pressure that they are to a greater or smaller degree transformed and difficult to recognize, especially as nearly all the fossils presumably have been crushed during the folding.

In some places the layers bend and wind so strongly that they resemble the entrails of an animal; in other places a mountain may consist of one single or a couple of huge folds. The peculiar fact is then observed that that which was once a valley is now a mountain-top, and a place where long ago a mountain towered up has now turned into a valley. The explanation is very simple. When a stratum is pushed upward, in this case when it forms a mountain-top, the upper layers of the top will, as it were, be torn apart, and thereby lose a great deal of their power of resistance. The opposite takes place when a layer, originally horizontal, is pushed down, forming a valley. In the hollow the layers will be pressed together, thereby adding to their power of resistance, so that the bottom of the valley will become hard. When a newly formed mountain chain like this begins to disintegrate, the tops will quickly crumble, first becoming level, then turning into valleys, whilst the original valleys, with their bottoms consisting of hard rock, will remain as mountaintops. When from a high mountain one stands looking across nearly 2,000 metres high cliffs, which were originally the bottoms of large valleys, and in imagination attempts to reconstruct the original mountain-tops which have now disappeared, one understands what enormous periods of time must have elapsed before this transformation was finished. However, it is only very old mountain chains which look like these.

When one considers these conditions it is easier to understand why the mountain chain is penetrated both lengthwise and crosswise by fjords and sounds. In reality all the islands along Greenland's north coast are fragments of a folded chain which was once far mightier.

It would be in vain to attempt to fix in years the age of this mountain chain; there is no means whereby one could measure the time which has elapsed since then. But it is not difficult to decide the relative age of the folding. The statements we have already made will have made it clear that the mountain chain must be younger than the coarse sandstone, which to the south had a horizontal position, and consequently must have been deposited before the folding commenced. The sandstone, which was superincumbent on the slaty limestone and the black schist with the graptolites, must therefore be younger than these strata, and this gives us a point on which to fix. From other regions of the earth we know that the graptolites found in the slaty limestone lived in the very earliest part of the Silurian Period. Consequently the coarse sandstone must belong to the Devonian Period, and the folding must therefore be younger than the beginning of this. From a previous expedition it is known that, to the north of the folding, horizontal strata from the Devonian Period are to be found, and above them strata from the Carboniferous Period. The mountain chain must thus have arisen during the first half of the Devonian Period.

During an Arctic sledge journey, when each day brings a crowd of new impressions, there is seldom an opportunity to sit down and look at matters as a whole. One examines the landscape at a distance through field-glasses and makes a guess at what kind of rock went to the building of the districts through which one passes, and when one stops it is the fossils and the rocks which are examined closely through a magnifying-glass. One therefore returns from such a journey with a mass of details which are only gradually brought together so that the larger contours appear.

However large and beautiful the view from one of the highest tops of the folded chain may be, one is merely looking at a slight section of the whole chain, and one must therefore in imagination attempt to make a connected picture of the entire folding in order to find out whether other regions have also been subjected to this enormous catastrophe of nature.

If one follows the westward direction of the mountain chain, one finds that its continuation is a large mountain chain in Grinnell Land known from earlier times, the so-called "Albert and Victoria" mountains. Down towards Ellesmere Land the foldings gradually disappear. If this section of the folding is included, the Greenlandic mountain chain has a length of approximately 1,000 kilometres in other words, it is as long as the Caucasus.

If the direction of the mountain chain is followed eastward we find as its continuation a submarine ridge across to Spitzbergen, and in continuation of this ridge there is on Spitzbergen a large folded chain, of the very same age as the one in Greenland. The mountain chain on Spitzbergen, however, is merely a part of a large system of folds which via Bear Island runs down to the north of Norway, and thence forms the whole of the Scandinavian mountain chain which continues through Scotland. This mountain chain, which is called the Caledonian Folding, has up to the present been known only east of the Atlantic Ocean, from Scotland to Spitzbergen. The most important geological discovery of the Expedition is that it succeeded in pointing out the Greenlandic section of the Caledonian Folding to the west of the Atlantic Ocean.

As already mentioned, the North Greenlandic series of strata ended in coarse sandstone, which during the Devonian Period was then folded up into the mountain chain. What subsequently happened is not known with certainty. Great stretches of North Greenland, and first and foremost the mountain chain, have during part of the Mesozoic Period been raised above the sea-level, and during this period the mountain chain became constantly lower; but no fossiliferous strata have been preserved, so one must fall back on hypotheses regarding the conditions. During the Tertiary Period there must certainly have been land with semitropical forests here, for remains of such are to be found on Grant Land, which lies right opposite.

Then the Ice Period came. It spread its ice masses across practically the whole of North Greenland. At any rate it brought blocks containing Silurian fossils up to some of the highest summits of the mountain chain. The inland-ice has now, especially to the west, receded about 100 kilometres, and although this stretch of time since the Ice Period is so short, in comparison to the periods already mentioned, many changes have nevertheless taken place in the North Greenlandic landscape since the Ice Period. During a certain period North Greenland was lying at least 210 metres lower than now, and large sections of the plains which now consist of the coarse sandstone were then lying under the surface of the ocean. At that time there were many more fjords and sounds on the north coast. We may state with certainty that subsequently the climate was not colder than it is now, as the glaciers have not shot out across the old sea margins which one comes across more than 200 metres inland. Right up to a height of 135 metres one finds shells of mussels from that time, all of them forms which at present exist in the same neighbourhood.

This description of the development of the North Greenlandic landscape would be incomplete if one did not finally mention the youngest and one of the most powerful of the series of strata—i.e., the inland-ice.

It is well known that almost the whole of North and Middle Europe during the Ice Period was covered by a connected mass of ice, which, like a shield, arched its back from Scandinavia out across the surrounding countries. This was also the case with the whole of Canada and the northern part of the United States. In Greenland the ice has remained, one is yet in the midst of the Ice Period, and a journey from the south of Greenland towards the north is like experiencing anew the coming of the Ice Period.

If the journey is commenced at Godthaab or Holstenborg there is still 100 kilometres from the coast to the inland-ice, and even from the highest coastal mountains one cannot as a rule see it. Wild, riven mountains form the landscape, and occasionally the sun is reflected in the shiny surface of a glacier, or shines on the snowdrift, which is so big that it does not melt in the short summer.

Such a snowdrift may be the beginning of an Ice Period. If a succession of years come with much precipitation or cold summers the snowdrift will grow bigger. The snow will be pressed into ice, the whole thing begins slowly to slip and float down a mountain-side, and there one has a glacier.

If one travels northward one comes to neighbourhoods which are nearer to the state of the Ice Period than are the districts in South Greenland. First one will see Disko Island, which, with its large lava plateaux carrying on their heights a flat glacier cap, reminds one very much of the inner regions of Iceland. To the north lies the peninsula Nûgssuaq, where in many places one might well believe oneself removed to the Alps, as innumerable long, narrow valley-glaciers shoot down from a height of nearly 2,000 metres towards some large plains in the interior of the peninsula. Finally there is the Bay of Umanaq, which is a slice of Spitzbergen magnified and beautified.

The journey from Godthaab to this point has already been a long one—as far as from Copenhagen to Switzerland—and a large edition of all Europe's glacier-world has passed in review before the traveller; and still they were all merely local glaciers independent of the inland-ice, which we have not yet. seen. First in the most northerly of the Danish districts, Upernivik, one gets from the outer coast the right impression of it.

Once it was all merely a snowdrift which did not melt during a cold summer; then it was a small glacier which lay hidden in a valley—a glacier which grew, spread out, and filled the valley, merged into other glaciers, reached the ocean, and put great icebergs into the water. And the glacier increased constantly; the low land was quite hidden, as were also the low mountains. The ice grew up round the highest summits of the mountains, the Ice Period had set in, all land had disappeared, and the perfectly even surface of the ice did not show a trace of the mountains and the valleys which it covered.

Thus the Ice Period arose, and the journey from Upernivik to Melville Bay represents the last chapters of this history. The land in front of the ice becomes increasingly narrow; every valley is filled with ice. Large glaciers shoot out between and across islands and skerries; near the Devil's Thumb the coast consists as much of ice as of land, and north of this point only occasional small islands or nunataks push up. For miles the coast is one continuous wall of ice.

If one travels by sledge one may find that the ocean-ice by Cape York is broken; one must then travel for about 100 kilometres across the inland-ice before one reaches Thule.

Only the man who has travelled for weeks day after day along the inland-ice without seeing land can rightly appreciate the nature of the Ice Period. The first thing which impresses one is the enormous dimensions with which one must reckon. The landscapes, which with their big fjords and huge mountains seemed so large from the sea, now lie far beneath the spectator as narrow rims of land, quickly disappearing to give room for a perfectly even snow-plain. A journey across this from north to south would be as long as from Copenhagen to the Sahara, and during this journey the landscape would not alter for a single instant. Nowhere would one see land; infinite as the sea lies this snow-field, and life is represented neither by animal nor plant. Even the Sahara has its oases between which men and animals move about; but here is nothing but snow—this is the region on earth most inimical to life.

In the central parts of Greenland it never rains, as the temperature there is permanently below minus 20° C., but it is not yet quite clear in which seasons the snow falls here. All information points to the probability that a tract exists there where wind is rare; the snow is very loose. But such an enormous surface of snow will, of course, lower the temperature of the air. It thus becomes heavier; it sinks and presses from the centre across the ice in all directions. Consequently, at the edge of the inland-ice, there is nearly always a wind from Central Greenland.

The edge of the inland-ice varies very much. If the ice covers an uneven Alpine landscape one will find in the border zone hills and valleys, with streams and lakes on the surface of the ice. Occasionally a mountain-ridge or a valley may be followed for many kilometres into the inland-ice. In such places, where the underlying ground is uneven, or where the ice is in strong motion, the ill-famed crevasses arise; these, then, are only met with near the edge of the inland-ice.

If the land in front of and beneath the ice is flat, the surface will, as a rule, be even and free of crevasses. This is the case in the most northerly parts of Greenland.

It has already been mentioned that the inland-ice consists of glaciers which have merged into each other; nearly all of them shoot out towards the sea, where they form icebergs when greater or bigger blocks are thrown off and float away. The lower layers of such a glacier are often mixed with soil and stones, which it has ploughed up into itself on its way across the underlying ground. It is well known that all the soil of Denmark has been carried down from Scandinavia by the inland-ice—a pretty example of the quantities which the inland-ice is able to carry with it.

When a glacier reaches the sea, greater or larger icebergs will, as already mentioned, be set free and float away. In several places of Southern Greenland this may take place unhampered, as the sea in front of the glacier is never covered by ice. But in Northern Greenland the fjords and parts of the ocean are covered every winter, and this prevents the icebergs from floating away from the glacier. Certain particularly strong and large glaciers, as, for instance, the ice stream of Jakobshavn, are, however, all through the winter capable of bursting the ice cover; but these are exceptions, and as a rule there are towards the spring in North Greenland a closely packed mass of ice blocks collected in front of the glacier; these float away when the ocean-ice in front of them melts. The further north one goes the longer the ocean-ice remains lying, and the broader is, consequently, the belt of icebergs in front of the glacier.

In the fjord north of Thule the ocean-ice lies from October to July, and the great Moltke Glacier by the head of Wolstenholme Fjord has, in the spring, a belt of closely packed ice in front of it, which may be a couple of kilometres broad. When the ocean-ice drifts away in the beginning of July, the glacier-ice is so firmly packed together that it remains lying, and not until the early part of August does the ice split with a mighty roar, and the whole fjord is covered with pieces of ice.

On the north coast of Greenland the ocean-ice does not drift out from the fjords; thus the icebergs are also unable to float away, wherefore, as a rule, one meets with them here. The belt of icebergs in front of the glacier remains lying over the summer; it becomes constantly more firmly pressed together; at the top it melts to the same degree as does the glacier mass behind it, and finally it is no longer a collection of loose pieces of ice, but one huge block, which increasingly broadens and is connected with the glacier behind; in other words, it has become the foremost floating part of the glacier, and in this way arises the so-called floating inland-ice, which, in the Northern Hemisphere, is only known in the northern extremity of Greenland.

The surface of the ocean-ice in front of the glacier is in the course of the summer subjected to exactly the same degree of melting as the floating inland-ice, which, because of this very melting, has become increasingly thinner towards the point. The result is that the outermost part of the glacier-ice and the ocean-ice assume an extraordinary similarity; they merge into each other, and in certain fjords—for instance, Victoria Fjord-there is on the whole no definite line of demarcation between the ocean-ice and the glacier-ice as they merge evenly into each other.

To understand this question one must examine the conditions of summer here in the most northerly regions of the world, bounded to the south by the entire inland-ice and to the north by the permanent ice cover of the Polar Sea. In the following we will attempt to describe the climate of North Greenland and its relation to the inland-ice.

The whole of South Greenland receives sunlight by noontime of the shortest day of the year. The rays of the sun do not, however, reach to Holstenborg on that day; only on the following day does it show above the horizon, and for every succeeding day it sends its rays further northward, putting an end to the dark period. In the course of January the sun reaches the whole of Danish Greenland, with the exception of Upernivik; in the course of February it reaches the Cape York district, and not until March does it shine on the mountains of Peary Land, after a dark period of nearly four months. During the latter half of the dark period, in January and February, and also in March, the temperature has been down to about minus 40° C. the whole time. In the beginning of April the midnight sun commences, but the orbit of the sun is so flat in these latitudes during this month that its power is only slight. The air is warmed up to about minus. 23° C., but by the 1st of May the land still lies in its winter state. In the middle of May the first sign of spring is apparent, as snow-flakes lying on stones which turn towards the sun evaporate, and occasionally even a drop of water may be observed. A puff of wind, and it is forthwith once more turned into ice; but a moment after it reappears, and the patch of snow on the stone has become slightly smaller. In the beginning this melting and evaporation take place to a very small extent, but by the middle of May the development becomes more rapid. By noon the sun shines brilliantly on the mountains, which are still entirely covered with snow; during the afternoon a fog is formed round the highest summits, spreading more and more; in the evening it has become thick, and a fine layer of snow crystals falls on ice and land. This is part of the snow which evaporated at noon. The next day the sun again gains in strength; on the mountain-side, where its rays fall almost vertically, it makes light work of the loose snow crystals which have fallen during the night; they evaporate rapidly, and the evaporation of the firmer snow masses then continues.

The sun, however, has hardly any power on the horizontal ocean-ice; its position is so low that the rays fall obliquely, wherefore the snow crystals which fell during the night remain lying and do not evaporate. So in the. month of May one may see snow-bare patches on land becoming increasingly larger, at the same time as sledge tracks on the ocean-ice slowly but surely are snowed under. In this way quite considerable quantities of snow are transferred from the land to the ocean-ice. Naturally, during this period fogs are very frequent; during our journey we had only five quite clear days out of the four weeks about the 1st of June.

The whole of this development has taken place under a temperature of between minus 10° C. and zero. Simultaneously as the temperature becomes positive, about the middle of June, the fog ceases, as the snow is no longer transformed into steam, but begins to flow down the mountain-sides as water. The first running water was observed on the 15th of June, and with that the spring thaw on land had set in in earnest.

But the ocean-ice still remains in its winter state, covered by a thick layer of loose snow. During the first days of thaw this snow falls together, becoming firm and hard, and by Midsummer Day one may still find firm winter going for the sledges on the sea.

The air becomes increasingly warmer and about the 1st of July the thawing of the ocean-ice commences. It takes place with surprising rapidity. In the morning the snow is still rather firm, in the evening it is soft, and on the next day there is slush in all hollows; a few days later all the snow has melted, forming pools and lakes on top of the ice. The thaw on the ocean-ice is over in about a week, so that there is only a slight degree of melting in the course of a summer. The water in the lakes on the ice is, of course, 0° C., and the low sun is only able to melt the snow where it shines directly on it. As we all know, a certain amount of heat is used up by the melting process, so that the air immediately above the ice becomes cooler; this cooling is occasionally so great that a thin layer of ice is formed on the lakes. It is obvious that it cannot be any melting on a large scale which takes place during July and the first half of August on the ocean-ice. In the latter half of August the melting stops, the lakes are again covered with ice, and already by the middle of September they are frozen to the bottom.

Such is the summer on the ocean-ice and along the coast; but if one goes up into the mountains on land one soon discovers that the development is quite different there. The first thing one observes is the drought which prevails; large stretches lie absolutely dried up, and one notices at once that nearly all the snow has evaporated while the temperature was yet below zero. This will be understood more easily if one takes into consideration that the downfall is only one-sixth of the downfall in Denmark. Water running along the ground, which is so common further towards the south, is almost absent here. It is only under the glaciers and the snowdrifts that one finds water, and in these places is vegetation.

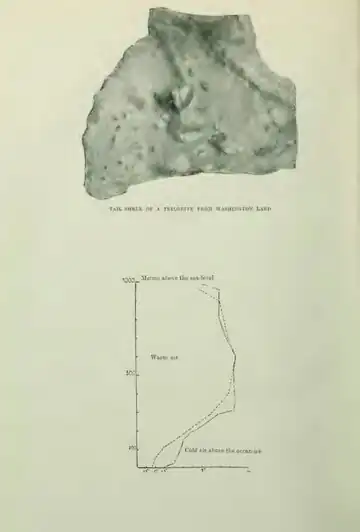

It is also quickly noticed that in July it becomes warmer as one ascends from the coast. In order to examine this peculiar condition, it was decided that Knud Rasmussen and Wulff should take the temperature on the coast every hour for twenty-four consecutive hours, whilst I was to ascend a thousand metres high mountain, examining the warm layer of air which must evidently exist. We chose a steep coastal mountain by Dragon Point which was 990 metres. I commenced the ascent on the 18th of July—that is, at the height of summer—at six o'clock in the morning, reaching the top at eight o'clock in the evening of the same day; the descent was commenced an hour later, and I was once more down by the tent at two o'clock in the morning of the 19th of July. The diagram will show the results of the readings.

One notices at once that immediately above the ocean-ice there is a layer of cold air which, in the course of the night, is further cooled down to below zero, whilst by noon it is somewhat above plus 3° C. Above this layer of air, which is 250 metres thick, lies another layer which at a height of about 1,000 metres is succeeded by a cold layer of air. The middle layer has through both day and night a temperature of nearly plus 9° C. At a height of 600 metres, then, there is during the night a temperature of 10° C., and during the day it is 6° C. warmer than on the coast. During our hunting expeditions we had rich opportunities to prove that this warmer layer of air was an everyday phenomenon in the most northerly part of Greenland during July and the beginning of August. It would take us too far here to examine the reasons for the existence of this warm layer, but it is obviously of great importance to both plants and animals, and it is surely a contributory cause of the existence of such large ice-free reaches along the north coast of Greenland.

The lower cold layer of air immediately above the ocean-ice will, of course, protect this from too great a degree of melting, and as one must assume that the under side of the ocean-ice melts, it seems reasonable to deduce that this ice every year becomes thicker upward, as the downfall of the year is partly deposited as a layer of ice on top of one already existing. In exactly the same way the floating inland-ice grows, and, as we have already mentioned, there is in Victoria Fjord no line of demarcation between ocean-ice and glacier-ice. In several other fjords there is a ridge of pressed-up ice between the two types of ice, as the glacier-ice presses forward against the immovable ocean-ice: but the surface of the ice on both sides of the ridge is perfectly even. The thickness of the ocean-ice may be put at approximately 5 metres, whilst the floating inland-ice may be 30 metres or more, especially some distance behind the edge of the glacier.

Loose pieces, consisting partly of several years of ocean-ice, partly of floating inland-ice, will occasionally drift out from the fjords through channels and lanes or, on rare occasions, when the fjord is ice-free. They may be found in the Polar basin north of Greenland, and are especially common in Robeson Channel. Nares Expedition called this formation "palæocrystic" ice, but not until now has it been known how it arose. The Eskimos call it "Sikûssaq"—i.e., ice which resembles the ocean-ice.

Only in the most northerly regions is the ocean itself covered by inland-ice, but wherever one travels in Greenland one feels this inland-ice as the great background of existence in these latitudes. Against this background life must be viewed, and that which in other and more favoured neighbourhoods may seem mean here, immediately before the Ice Period, becomes rich and remarkable.

- ↑ "Skjærgaard": the belt of rocks and islands girding the coast.—Trans.

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)