Greenland by the Polar Sea/Appendix 3

THE ROUTES OF ESKIMO WANDERINGS INTO GREENLAND

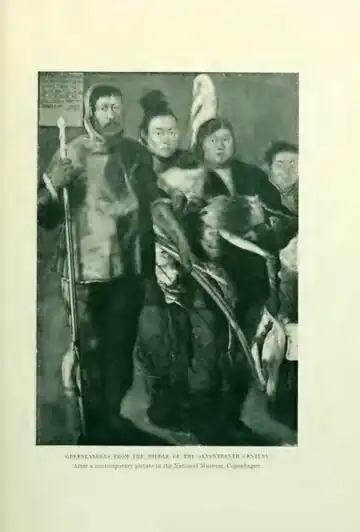

THE beginning of the history of the Eskimos, more than that of any other people in the world, is hidden in darkness; so far no explorer has been able to tell with certainty whence they came, and the tribes themselves veil their origin in obscure myths which give only sparse information. The only thing we do know is that, when these 40,000 people stepped into the light of history, they were spread over half of the world's Arctic periphery towards the harsh, ice-filled oceans whose coasts no one else could inhabit. On this mighty stretch of coast of more than 10,000 kilometres, where they bridged points as far apart as the East of Greenland and Alaska, the Aleutic Isles and Siberia, they have understood, as no other hunting people, the art of self-preservation, and in the midst of a merciless fight for existence they have created a culture which compels the greatest admiration of all white men.

Now, where had this people its first home?

William Thalbitzer has, by a study of the oldest myths, come to the conclusion that various circumstances point to districts towards the Far West. Thalbitzer writes in his book, "Greenlandic Myths of the Past of the Eskimo," p. 80:

"So far away from their goal, a thousand years ago or more, the wandering commenced which led to the coasts of Greenland. At that time the chief camp of the nation was by Behring Strait. There we find the original forms of the language and the culture which, later on, the wanderers towards the east continued and adapted on the coasts of David Strait. They probably arrived here in the tenth century of our reckoning, perhaps somewhat sooner, perhaps somewhat later, spreading themselves during successive centuries on one side down towards Newfoundland, to the southern border of Labrador, and on the other side across Smith Sound along the west coast of Greenland to Cape Farewell, and north of Greenland a goodly distance down along the eastern coast. The Stone Age people which the Icelandic Vikings met in the Middle Ages, and to whom they had to yield in the end, the same people which the English discoverers of the sixteenth century found again in larger numbers both on Baffin Land and in Greenland, was not a very old population on these coasts; their forebears had lived not many generations ago in the lands of the evening sun, far towards the west, by the mouths of the great rivers on both sides of the Rocky Mountains."

Another authority, Professor Steensby, is of the opinion that once they were a North American inland people with the culture of the fisherman and the hunter, whose origin must be looked for by the great lakes and rivers which have the Rocky Mountains to the west and Hudson Bay to the east. Pursued by inimical Indian tribes, they have slowly withdrawn towards the Arctic coasts, and here they accommodated themselves to an existence which, at the outset, permitted an adaptation of their experiences from lakes and rivers to the sea-hunting which subsequently through the centuries developed them into a people whose purely technical culture and ability to support themselves within their own territories is unique among men.

Since they arrived at the sea the Eskimos, according to Steensby's theories, have spread both towards the west and the east, so that, as we have already mentioned, we find their western border on the Aleutic Isles and East Cape in Siberia, whilst to the east we meet them on the east coast of Greenland. In the survey which we will here give to illustrate the ethnographical results of the expedition, we will, however, consider merely their wanderings towards the east.

Now, what was the reason for all these wanderings?

Why have the Eskimos never been able to gather in larger colonies, similarly to other people, and seek aid in the fight for existence in the security attendant on great numbers herding together? Where a whole people is concerned it is not a sufficient explanation to point to the native restlessness of the hunter, which forces him to examine the coasts of the lands and work his way towards unknown hunting-grounds. When the Eskimos spread out so widely across the world it was simply because their means of existence, and the number of animals to be caught, demanded that they must fly away from each other. It took a large stretch of ground to provide the single individual with the necessaries of life; the fewer the hunters the better were the chances, so they migrated eastward and westward along the coasts in little flocks, as long as they were not stopped by purely geographical conditions.

It is generally stated and insisted upon that the Eskimos on their wanderings towards Greenland have followed the tracks of the musk-ox and reindeer. I wish to emphasize that it may be taken for granted that, after the Eskimos discovered the ocean and its great sources of riches, they were only interested in the coasts where the movements of the aquatic animals gave rise to conditions preferable to those offered by the fish of the lakes and the game of the land. For this reason they have for many generations concentrated on inventions which facilitated the catching of food from the sea. The land game often gave an opportunity for great hunting expeditions which resulted in considerable amounts of supplementary provisions, but they were always looked upon as a subsidiary means of existence. If on their way the Eskimos happened to come across large herds of musk-ox and reindeer, these might occasionally be the deciding factor for the wintering camps, but otherwise the sea route, and the advantages or the difficulties which it offered, must have been the sole determinant for their journeys. In the following we will show more clearly what is the cause of the seals being so closely bound up with the Eskimos' life.

The high Arctic coasts demand to a greater degree than any other regions a highly developed winter culture. Cold and darkness must be overcome through long and pinched months when there is often no possibility of hunting, and for this period food must be put aside during the more favourable times with the food—seal meat—follows blubber, which makes the huts as warm as summer for women and children. Cold houses are regarded as being more dreadful than anything else.

To begin with the food, it is necessary to point out at once the way in which the Eskimo differentiates between the flesh of land animals and the flesh of seal or whale. The flesh of musk-ox and reindeer is considered not durable, especially when it must be shared with the dogs. Further, as the only article of food it is not always sufficiently rich in fat for this cold climate, where the consumption of much fat means bodily heat. For this reason it has always been looked upon as a supplementary food, which should preferably be eaten together with stronger and fatter meats.

The second factor in Eskimo life, and one which is no less important, is the artificial heat required in order that one may live and thrive; for it must not be forgotten that the Eskimos spend half their life indoors with everything indispensable collected round the train-oil lamp. This lamp is the sun of the family, and the only light during the period of Polar darkness. With its mild warmth it makes even the smallest hut cosy, and over its flickering flame are cooked all the meals, round which the Eskimos gather as for a feast. Clothes and kamiks, which protect them against the cold, are dried by it, and on the whole it makes it definitely possible for women and children to hibernate comfortably through the harshest part of winter.

It is, of course, possible to obtain fat from reindeer and musk-ox both for light and warmth in a hut. But it is far from being the same heat, and it also causes much more trouble. In addition to this, the lamps of a house demand such a large supply of fat, as they, according to custom, must burn both night and day, that an extremely great number of animals would have to be killed before one would be in a position to meet the winter calmly. And it is only during the autumn and the early part of winter that the animals are fat. Even after the most fortunate hunting excursions it is difficult to obtain sufficient fat to supply both men and lamps.

All these purely practical view-points, which play such an important part in their daily life, have been given to me by old Eskimos who have themselves taken part in folk wanderings, and they seem to demonstrate that an Eskimo, when once he is used to the flesh of aquatic animals and blubber, reluctantly substitutes anything else for it. This alone satiates his appetite and enables him to convert a stone hut into a patch of summer amidst the Polar frost. And one must remember that the Eskimos are people who appreciate a good time, and that the cause of their journeys is chiefly a desire to come to a place where conditions are better than those which they enjoy at the moment.

When we assume the correctness of Professor Steensby's theory, that the Eskimo culture as we know it has arisen round Coronation Bay, we can follow a line of wandering towards the east which runs southward from Baffin Land, and then via Labrador's coast goes almost right down to Newfoundland. Everywhere on these stretches the catch of marine animals has been decisive for all travelling dispositions. Another direction of migration goes north to Lancaster Sound and North Devon, where, by Jones Sound, it divides into two routes, some of the Eskimos going eastward and some of them westward round Ellesmere Land. By constant and successful hunting of seal and bear, the former have comparatively quickly reached Pim Island, and the subsequent crossing to Greenland is obvious—for to the north lie trackless districts with pressure-ice, whilst at this point, where Smith's Sound is at its narrowest, one may cross on easy ice to a large and promising land.

This route was used by Baffinlanders who immigrated into Etah in 1862 under the great Qidtlaq. The same route southward was taken when the tribe, after six years' sojourn in Greenland, attempted to return. Somewhat later, the Polar Eskimos undertook a wandering along this route, and wintered for a couple of years on Coburg Island by the mouth of Jones Sound.

The first immigrants to Greenland reached the land by Cape Inglefield, and thence they spread out both north and south. The parties which chose the routes to the south soon found excellent hunting-ground in Melville Bay, and further ahead in other parts of Greenland; whilst those who went to the north from Cape Inglefield gradually settled down in large colonies along Inglefield Land and Peabody Bay. Excellent conditions were found everywhere here, whilst the excursions which the hunters undertook to the north comparatively soon proved that there was no possibility of expansion northward through the narrow channels, where the ice was a chaos of pressure-ridges, and where the seals consequently were found only in small numbers. The land itself was covered by glaciers and had no ground for game, and at the same time the geological formations, limestone and sandstone, provided uncommonly poor material for the building of houses.

Thus for many generations the Eskimos presumably flocked together in this neighbourhood, comparatively small, but fit for habitation, and this explains why we found such an unusually large number of winter-houses on the stretch between Cape Inglefield to Humboldt's Glacier. As gradually they began to suffer from the consequences of over-population, they decided to follow those which constantly passed southward towards the much more promising coasts where seals and whales abounded.

The Polar Eskimos have a distant recollection of a time when all countries were inhabited. People increased until they did not appreciate each other and found that neighbours were a nuisance. Although one must be very careful in making history from the old myths, it is nevertheless probable that the account of the great blood bath round Marshall Bay alludes to a period when the district here was subjected to a blood-letting which overtook the people because they were too numerous.

We now return to the tribes which went along the west coast of Ellesmere Land, and which are of especial interest to us when we discuss a route of migration north of Greenland. For a while they must have felt comfortable in the peculiar and ice-free tracts in Ellesmere Land, Grinnell Land, Grant Land, and Heiberg Land, where existed and still exists great profusion of game. But the sealing possible in the narrow sounds, where the ice often did not break at all, was far from satisfactory, and the longing for the sea therefore led to a speedy departure. Some of the Eskimos went into the land through Bay Fjord, and found a convenient crossing over Ellesmere Land down. to Flagler Fjord, from which the passage to Greenland takes merely a couple of days. Others penetrated to Lake Hazen through Greely Fjord, and the abundance of salmon in the lake and the large flocks of musk-ox and hares have for a while made them give up the thought of pushing further ahead. At that time not a few winter-houses were built; these were found in this neighbourhood by Greely's Expedition. The way from Lake Hazen down to the sea by Lady Franklin Bay and Hall Basin is very easy to find, as great cloughs and rivers run down from the lake. In bays and creeks in the near vicinity of the coast there is rather good hunting of bearded seal, famous for its thick layer of blubber and its strong skin. The hunters by Lake Hazen have probably, as did the Eskimos who lived here during Peary's expeditions, gone down to the sea to hunt every spring; thus we find them as neighbours to Greenland. Before we had a thorough knowledge of Greenland's north coast, it seemed convenient to let these people continue from the tent-rings by Thank God Harbour further north along the coast, and thus arose the idea of the invasion of the east coast via the north of the country. In the following we will refute this opinion, and show that such could not have been the case. For the Grantlanders, stopped by natural conditions, have either gone southward on the ocean to Inglefield Land, which could easily be reached in the course of a couple of months in the spring, even if we allow for a family removal; or they have gone behind the lands down to the route which their kindred found across Ellesmere Land.

When we went to the great fjords on the north coast on the second Thule Expedition it was natural that we should harbour great ethnographical expectations with regard to these tracts, as the possibility of a previous habitation and a folk-wandering connected with it could only be decided by an examination of these regions. The majority of explorers presupposed an earlier habitation. Nearly all theories inclined to the view that the migration into Greenland has taken place not merely from Ellesmere Land via Cape Inglefield, both southward and northward, but also that a wandering has taken place north of Greenland to the east coast, and that this invasion has received its main contingent from those who came down to the coasts by the route Greely Fjord to Lake Hazen.

Without special knowledge of Greenland's north coast, it seemed natural to draw these conclusions, because Eskimo tent-rings had been found as high up on the east coast as the north side of Independence Fjord, both by the Danmark Expedition and by the first Thule Expedition. Winter-houses on the east side were found as far up as Sophus Müller Point, and now the problem was to find the connection with these by winter-houses or at least by traces of a wandering along the north coast.

It will be remembered from the travelling description that, although we followed the coast, everywhere hugging the land, and even occasionally went right up on the ice-foot, we did not succeed in finding the faintest trace of a previous habitation, this despite the fact that we and our four Greenlanders incessantly had our attention directed to this problem. Even in Sherard Osborne Fjord and Victoria Fjord nothing was found, however often we traversed on our hunting excursions, both on the upward and the downward journey, all the land which was accessible. Even a place like the Whirlpool in I. P. Koch Fjord, a natural sealing centre, had never been visited until we discovered it.

As a result of my experiences from this expedition I must insist that no Eskimo wandering can have taken place north of Greenland, and I will attempt to advance my arguments on this point.

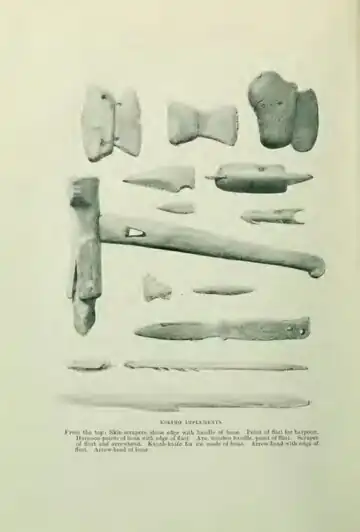

During a folk-wandering where women and children are included the wanderers would never voluntarily go into quite trackless districts. The pressure-ice from Polaris Promontory to Sherard Osborne Fjord would constitute quite a considerable obstacle for the transport of a family and household goods; and we must of necessity take into account the primitive travelling gear which was used. The sledges were made entirely from whale rib or from pieces of wood patched together; they were small and always very fragile, for the Eskimos lacked the tools for proper workmanship. On these sledges were transported, during the great camp-breakings, stone pans, lamps, and skin tents, all of which were heavy and unwieldy articles; further, a kayak, if a man. possessed one, the spare clothes of the family, and whatever else they might own of tools and things which could not be replaced in a hurry. Even if all these articles represented merely the most modest idea of what a household would reckon as its property and worldly possessions, they were nevertheless difficult to transport and demanded proper roads. Those of the children who were too small to walk were strapped like phantastic bundles of skins on top of the loads, and as, during long removals, out of consideration for the food, often only a few dogs were kept, the adults had, as a rule, to assist in the pulling and pushing of the sledges. It is easy to understand that for such a transport a reasonably good condition of the ground would be necessary.

As a rule the removals took place during the months of April and May; there was then warm sunshine, and the children, who must always be considered, suffered less from bad weather. During this season, when the seals begin to crawl up on the ice, there were also better prospects for hunting on the way if the game did not yield sufficient daily food. One must remember that no provisions could be brought, apart from a few meals, so that all food for men and dogs must be acquired on the way. During summer and autumn no travelling was undertaken in high Arctic regions like those we are now considering. In the summer no road was to be found, and in the autumn it would be unjustifiable to set out towards unknown districts with winter and darkness before one and no depots to fall back on. These depots, or meat-pits, on which life and welfare depended, must generally be collected during May, June, and July, these being the only months when one can reckon on a surplus. If one were in a locality where the summer and autumn catch were favourable, one might also reckon on August and September. With regard to conditions for travelling and hunting along the north coast during the months mentioned, it will be sufficient to refer to the preceding travelling description. The peculiar conditions of ice and snow forbid sealing to the extent which is necessary either for travellers with families, or for a stationary life in camp; and the ice-free inland tracts are not sufficiently extensive to yield game for wandering, not to mention for wintering, tribes. It must be taken for granted that the musk-ox has gone north of Greenland only in small and casual herds. As we found no winter-houses, tent-rings, fireplaces, or other traces of Eskimos, this negative result is entirely in accordance with the conditions for existence which nature offers.

This, then, disposes of the theory of a folk-wandering north of Greenland, for it would be unthinkable apart from winter stations by one of the fjords on the north coast. From the tent-rings by Hall's Grave, the most northerly known on Greenland's west coast, to the tent-rings by Independence Fjord, the most northerly known on Greenland's east coast, there is a distance of no less than 1,000 kilometres along the route which an Eskimo family would follow. From the houses in Benton Bay, the most northerly known on Greenland's west coast, to the winter-houses by Sophus Müller Point on the east. coast, there is a distance of about 1,500 kilometres along the sledge track north of Peary Land, or a distance approximately as great as from Upernivik to Frederikshaab. An Eskimo family would never traverse such a distance in one journey, but must have several intermediary stations with good hunting on the way. Further, the hunters must, in order to carry on from day to day, travel under the impression that the hunting along the route they follow will be increasingly better the further they go. Our expedition, which consisted only of selected men equipped with the very best of gear and weapons of our time, barely escaped from this coast, so poor in game, this despite the fact that we visited it in the most favourable season when hunting should be at its best.

Certain writers support their defence of a folk-wandering north of Greenland by pointing out that the climatic conditions in these regions were once different, and that at that time a heat wave passed over the north of Greenland with a milder climate, which gave quite different conditions of existence than the present. If we assume that this period coincides with the post-glacial heat wave known in Scandinavia—and there are many indications of this probability—the period of the milder climate would then be some 6,000 years ago; but the Eskimo wanderings probably took place 1,000 or 1,200 years ago, so that this heat wave cannot have influenced the migrations here mentioned; when they took place conditions must have resembled those of the present time.

In addition to the obstacles on the road and the conditions of the ice, which hinder the movements of the aquatic animals, there are also other natural phenomena peculiar to the north coast which must be taken into consideration. The great fjords, St. George Fjord, Sherard Osborne Fjord, Victoria Fjord, Nordenskjöld Fjord, I. P. Koch Fjord, and the other greater and smaller incisions right up to de Long Fjord, are all filled with floating inland-ice; and through this no seal is able to work a breathing-hole.

Another circumstance which, though of less importance compared with those already mentioned, nevertheless made an impression on our Eskimo members, is the uncommonly poor material for houses which is to be found; the coast consisted mostly of loose, slaty, and easily crumbling sandstone, unsuitable for the building of stone houses. An Eskimo would scarcely settle down here voluntarily. The opinion which has occasionally been voiced to the effect that the Eskimos, during their visit to the north coast, contented themselves with only snow-huts during the winter, is improbable, and betrays a complete ignorance of natural conditions in Greenland, and of Eskimo habits. Apparently one forgets that not in all seasons of the year, not even in all places, is it possible to build snow-houses. During autumn and the first part of winter, in September, October, November, eventually also in December, one only occasionally finds snow drifted together to such a consistency that it would be possible to cut out of it blocks for building material. And during these months no hunter would let his wife and his children lie freezing in a skin tent. The season of the snow-houses only comes when the first hunting excursion begins, with the return of the light period.

The lines of the Eskimo migration from the north to the east coast were previously drawn through Peary Channel, through which one could penetrate from Nordenskjöld Fjord into Independence Fjord without leaving the coast, conveniently hunting game on both shores. As we have now succeeded in proving that instead of sea one meets here with a belt of ice of considerable breadth, this short cut also is eliminated. Remains then only the inland-ice, in as far as it can be traversed behind Peary Land's north coast from Nordenskjöld to Independence Fjord. But the conditions for an ascent are very difficult here, because of the floating inland-ice and its crevasses; and even if these were passable, a sensible man with wife and children would hardly set out on a 200 kilometres long wandering through the waste if he did not know anything beforehand about the natural conditions with which he would meet. when at last the risky journey had come to an end. If a wandering from the north-west to the north-east of Greenland has taken place, there is only the way north of Peary Land; but no conditions for existence are offered here.

To sum up, all observations inade during the expedition point to the probability that in Melville Bay we must look for the great main route which has led the Eskimos from the North American Archipelago to Greenland.

The entire migration has gone southward, and even to the east coast they have come south of Cape Farewell. It has been maintained that the collections brought home from the north of East Greenland point towards north, but even such an argument appears to me futile to discuss. For it would seem much more natural to relate the North-East Greenlanders to tribes which have been offshoots from the colony at Angmagssalik, which has no doubt always been thickly populated. Right down to the time of the colonization there were people here who went north, and many hunting traditions point to a northgoing movement. Along this coast there are no passages which can compare with the stretch between Hall Basin and Independence Fjord. As these people from the sub-Arctic climate gradually settled down under quite different conditions and quickly became acclimatized and adapted their tool-making technique to a definite or exclusive winter culture, so everything found after them will bear the high Arctic stamp, although it must not necessarily have come southward from the north, wherefrom no way is to be found. And could any body imagine a folk-wandering—and that numerically a rather large one—traversing more than 1,000 kilometres along the coast without leaving the slightest trace? The tent-rings in Independence Fjord must therefore be due to reconnoitrings from Sophus Müller Point.

In full accordance with the views here maintained, we lose the traces of a folk-wandering, both on the west and the east coast of Greenland, in and with the localities where the sealing during the hunts of spring and summer cannot form the base of an existence such as the Eskimo desires.