Greenland by the Polar Sea/Chapter 1

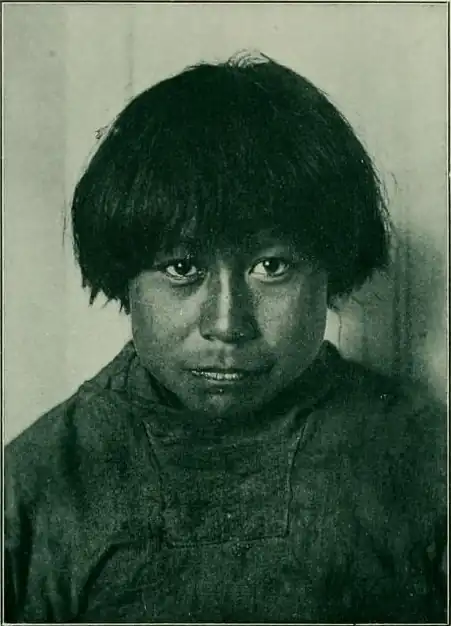

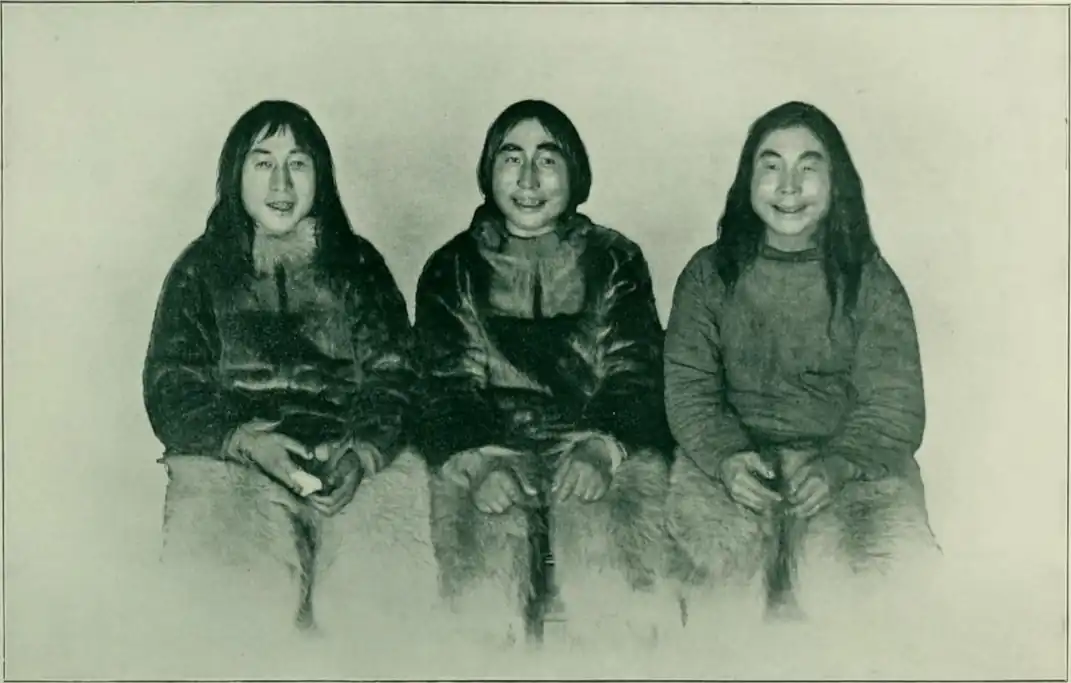

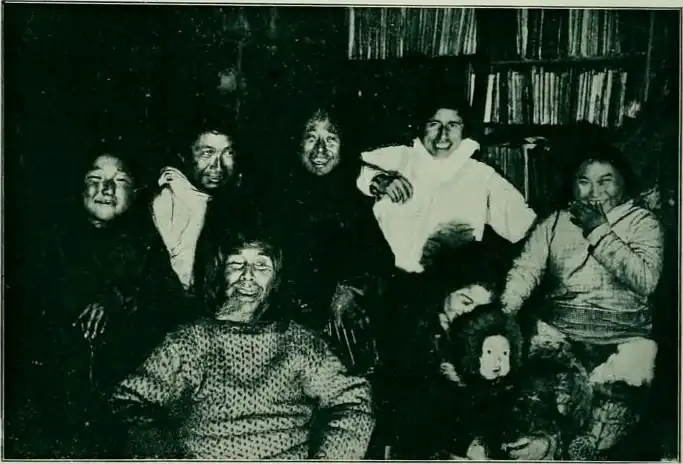

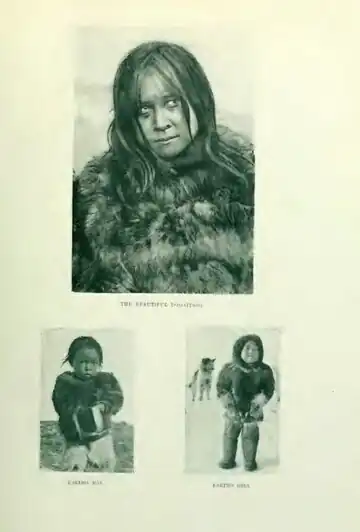

NORTH of everyone on our earth live the Polar Eskimos, whose simple and ingenious ways of hunting have made of their harsh and barren country one of those oases in the world where live genuinely happy people.

The first historical information we possess about their country dates from the year 1616, when Baffin discovered it. He, however, did not see any people, and it was only in 1818. that John Ross came into touch with Eskimo people of whom one had never heard before.

A memory still remains amongst the tribe of a woman named Maage (Gull), who prophesied that a big boat with tall poles would come into view from the ocean. And sure enough, one summer's day, just as the winter-ice broke and steep Cape York lay separated from the sea merely by a narrow strip of ice, the ship arrived and lay to by the edge of the ice. It was a marvel of ingenuity—a whole island of wood which moved along the sea on wings, and in its depths had many houses and rooms full of noisy people. Little boats hung along the rail, and these, filled with men, were lowered on the water, and as they surrounded the ship it looked as if the monster gave birth to living young.

This visit at first caused great anxiety and fear among the Eskimos, but later much joy. They did not believe that the white men were real human beings, but looked upon them as spirits of the air who had come down to the Inuits. The ship remained only for a short time, then turned towards the sea with the sun shining on its white wings and disappeared into the horizon.

Ross's visit to the simple and unprepared Eskimos certainly caused a stir, and I will therefore supplement the above phantastic narrative with something of that which is related in the Record of the Expedition.

It is told that the ship was lying alongside the edge of the ice when suddenly, to the surprise of everybody on board, on the ice were discovered beings in human likeness, dressed in pelts and with long, black hair flowing from their heads. With strange gestures they ran by the side of their dog-sledges. They were quite close to the ship when the big white sails were manoeuvred; and the result of this was a sudden about-turn and a scampering towards land in apparent fright.

A couple of days elapsed, during which every possible effort was made from the ship for getting into communication with the Eskimos, but without success. In his despair Ross at last had a huge standard erected by an ice-mountain between the coast and the ship; from this he hung a flag, whereon the sun and moon were painted above a hand which held out a heather plant. Furthermore, a bag of gifts hung from the staff.

This clever trick was, unfortunately, not well received. If the Eskimos had been frightened before, they were now terror-stricken with this mystic staff and its fluttering flag, which they obviously considered to be some dangerous ruse of war. Out of curiosity they circled round it for awhile, but having scanned for a sufficiently long period the strange signs and the friendly outstretched hand, they disappeared hurriedly towards land.

When this attempt miscarried a white flag was hoisted on the mainmast of the ship, and at the same time Sachæus was sent out on the ice with a small white flag in his hand. But the Eskimos did not appear to have any understanding of the peaceful purport of these manoeuvres, and the probability is that these sagacious experiments, which would merely have frightened and confounded the Eskimos still more, would have continued if Sachæus had not shown himself a master of the situation and asked Ross for permission to go to the kinsmen of his tribe, alone and unarmed. By this means communication was at last established.

The great meeting between the Polar Eskimos and the South-Greenlander took place by a broad fissure in the ice, so that they stood right opposite each other, with a natural obstacle between them for safety's sake.

Sachæus explained, not without trouble, that a peaceful people had come to them, and the Eskimos were just on the point of consenting to follow him on board, when Ross, who of course was eager to meet these strange men, suddenly appeared on the ice in his officer's full dress uniform, as given in the illustration of this scene in the Record of the Expedition. This phantastic apparition of a man nearly frightened the Eskimos away again; but as the friendship with Sachæus had already begun, and as he explained to the marvelling natives that this peculiar dress was merely an outward sign of the fact that the big man was lord of all white peoples, they let themselves be calmed down and followed him on board.

It is highly praiseworthy of the Eskimos that they, in spite of all the inexplicable things they saw, allowed themselves to be coaxed on board and, in the Chief's cabin with Sachæus as interpreter, to give wise and dignified answers to the many questions that were put to them. Imagine the impression they must have received when, presumably to amuse them, a grunting Scotch pig was let loose on deck—these men who were only used to wild animals! Or when they were treated to a conjurer's performance, and allowed to look at themselves in a concave mirror!

It is interesting to note that Ross sums up his impressions of them by stating that they all speak lovingly of each other and their families, and on the whole seem to live happily, without knowledge of disease and war.

Already as a child I had in Greenland heard much about the Polar Eskimos, but it was mostly vague tales of savage cannibals, terrible hunters who lived with the North Wind himself, right at the "end of the world," where it was always night and where no summer melted the ice of the seas.

"I must go to those people," I decided as a twelve-year-old boy, and this decision, which later on I never succeeded in slinking away from, has, through repeatedly staying among them, led, so to say, to my reception into the tribe as one of their own, as a friend and fellow-hunter.

No hunter exists up there with whom I have not hunted, and there is hardly a child whose name I do not know; but then, the tribe consists of no more than about 250 individuals.

These men, who have no fixed abode but live, as does their prey, ever on the move, are born Arctic explorers. From childhood they are hardened by an unmerciful cold, and their means of livelihood exposes them almost daily to severe physical strain and sudden dangers which sharpen their presence of mind and make their contempt of death a matter of course, the consequence being that they are unsurpassed as companions on Arctic Expeditions.

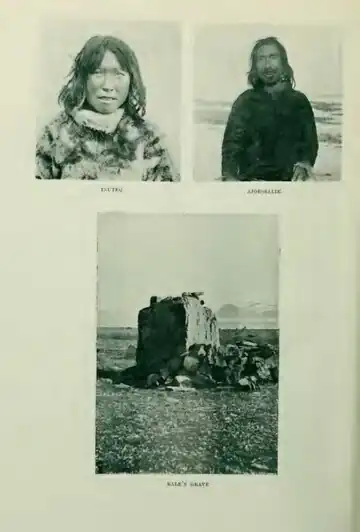

Kane, Hayes, Hall, Nares, Peary, the Crockerlands Expedition, and, last, but not least, I myself recognized this, and through these expeditions, comprising all those which during the last seventy-five years have explored and charted the northernmost parts of our earth, the Eskimos have in different ways done their share, which must not be undervalued.

In this record, however, I will dwell especially on Peary, because his Arctic travels represent a chapter of the history of the Polar Eskimos.

The Eskimos owe not a little to Peary, but, on the other hand, without their help Peary's name might have been less famous than it is now; for they followed him on all his expeditions, left home and country and kind and put their whole existence at stake in realizing the phantastic travelling schemes of a foreign man.

The way in which the Eskimos risk their lives, when once they have promised a man their assistance, for the solution of problems, wherein they themselves often see merely manifestations of the many queer ideas of the strange white men, shows plainly their absolute contempt of death, and what an abundance of courage they possess.

They are not of the type which, like dogs, put their tails between their legs and run off when they meet dangers and the eternal hopelessness of pressure-ice.

The Eskimos are a roaming people, always longing for a change and a surprise-a people which likes moving about in search of fresh hunting-grounds, fresh possibilities, and "hidden things."

They are born with the explorer's inclinations and thirst for knowledge; and they possess all those qualities which go to make an explorer in those latitudes.

When an Eskimo family moves on to new ground, in a surprisingly short time it knows the surroundings for miles around—paths, short-cuts, plains, mountains, all the natural features which a hunter must know so that he may track down his prey. They study the inland-ice and find places of easy ascent and sledge routes to other coasts and new chances. Soon the sea has no secrets regarding the movements and favourite haunts of its animals.

On the whole, the hunter likes to leave the old ways for the stimulating excitement which accompanies seeking and hunting under strange conditions. And he also knows how to value this quality and this inclination in others.

I shall never forget the happy sensation created among the hunters of the tribe when, in the spring of 1907, I drove up to them with Osarqaq and declared that I was on my way to Ellesmere Land. I had never seen a musk-ox, and now I had a longing to taste musk-ox meat. You see, according to their opinion there must always be a sensible reality behind one's actions. Oh, how well they understood me! They knew that it was "two suns" since I left my country and my family, and that I was still on the road with the same goal constantly in view. They respected that. I felt happy and touched when an old necromancer, Masaitsiaq, greeted me with a call to the effect that it was good that in my own country I had not forgotten the hunting circle of my old comrades; and then he declared that all the young hunters of the tribe would vie with each other in showing me the country which I had never seen before and the animals which I had never slain before. And everything happened according to his promise. Two of the best men in the tribe immediately declared that they would come. No considerations here, and no preparations; an Eskimo is always equipped for a long voyage. On the following morning we set out on the 1,250 miles long sledge journey, and hunted together for several months and shared the strangest experiences. And we travelled together as comrades, as equals; they would take no payment for the long time they were with me, away from their families; no, this was merely an episode in their lives, and they would certainly not be my paid servants.

In the same way they took part in Peary's voyages, so long as he travelled on land. It is therefore interesting to note the position they took up when the Polar voyage itself commenced. During the first expeditions they agreed with pleasure to go north, because they thought that the voyage might result in meeting with new people, in the discovery of new hunting-grounds, or, at any rate, of land fit for habitation. But later on, when they were told that they risked their lives for a geographical point only, a point somewhere in the desert of pressure-ice where neither men, nor game, nor land existed, then the toil seemed to them so utterly aimless that their participation now required entirely fresh motives. Partly there was the respect for Peary—I have often been told that "he asked with so strong a will to gain his wish, that it was impossible to say no"; partly, also, there was the wish to possess guns, wood, and knives which were the payment for participation. But their personal interest to reach the goal, their private ambition to arrive there, no longer existed. For twenty years Peary had seen among the Polar Eskimos the base of his expedition, and during this short period these people had jumped from the stone age to the present time in their technical civilization.

When Peary came there for the first time the tribe was in all essentials untouched. Guns were hardly known, the chief weapons on land being the bow, and on sea the harpoon. Long before Peary finished his last expedition all the hunters possessed the most modern of the breech-loading guns of our time. The old knives, which consisted of little splinters of meteoric stone, laboriously hafted in bits of reindeer skin or narwhal tusk, were replaced by the finest steel; and their sledges, which once were pieces of whalebone cunningly tied together to form runners, were now of the best ash or oak.

Long before Peary appeared a lively bartering with the Scotch whalers certainly took place; but a thing like a gun was a great rarity. Commercial intercourse with the whalers seems on the whole to have been very casual, and one may therefore say that it is Peary who has given the tribe its present effective equipment for winning a livelihood. Previous to the introduction of modern weapons it was obvious that the Polar Eskimos were subjected to the moods of the varying years. Their own simple and primitive weapons were beautiful and serviceable inventions; but the handling of them was an art, and when the condition of weather and ice, or even the movements of the animals, were unfavourable, it happened not rarely that they had to face bad winters through which they could only manage to exist with great difficulty. So far as their livelihood was concerned, Peary developed in them the white man's brain, which of course signified great progress in their material existence.

But the Eskimos did not forget to repay Peary what they thought they owed him; on his last two voyages to the North Pole about seventy to eighty Eskimos—men, women, and children—with several hundreds of dogs, accompanied him on the Roosevelt to the northern point of Grant Land. In other words, this included all the best young men in the tribe. And can anyone think of a more serious and extensive contribution to scientific exploration than this wholesale sacrifice of the supremest?

But Peary himself possessed qualities which made it possible for him to come to such an arrangement with his helpers. His great personal endurance, his repeatedly tested fearlessness, his capacity to manage year after year in such a way that he escaped well from it all—all this won the unstinted admiration of the Eskimos. They thought it good fun to risk something with a man like Peary—the great Peary of the strong will, the mighty lord of inexhaustible wealth, Piulerssuaq, who himself will surely some day be the hero of one of their tribal myths.

During my meetings with the Polar Eskimos I have often had occasion to hear them speak of him; and they have always been full of appreciation and proud to have been with him, even if one often feels that their respect for the man was greater than their love. I will recount a little incident which was told me by Odaq, who accompanied Peary on all his Polar travels.

It was in 1906, the year in which Peary reached 87° 14' and set a temporary record farthest north. Six Eskimos accompanied him, and these had for several days remonstrated with him that they would have to turn now if they should not die from starvation on the return journey; but Peary maintained obstinately that they must endure for a while longer. They had met with many mishaps. Open water had delayed them, and terrible blizzards in biting cold had hindered all progress; but as soon as there was a lull in the storm Peary got out of the snow-hut and made his way northward, always northward, into the ill-famed pressure-ice, fighting his way, clearing a path for the sledges and the worn-out dogs which followed, driven by the Eskimos. And Peary continued his slow walk against the storm with the sledges snailing behind him. Then came an evening after such a day when a longing for land, for wife and children and the delicious game far down southward seized the young hunters so strongly that they could see only death and destruction in all their desperate push northwards. They had not spoken much about it; but Odaq thought they looked so strangely at each other; and it struck him that none of them dared to mention land any more. He could bear it no longer, and went into the snow-hut where Peary lay sleeping. "I have come to speak to you for my comrades' sake," he said, "for further progress now would mean death for all of us, and I know that you will not turn. Send my comrades back; with the aid of the compass they will be able to find land, and I will go on with you so that you may not die alone."

And Odaq continued:

"Then Peary looked at me with such strange sadness, and it seemed to me that for the first time in all the days I had travelled with him his stern eyes looked kind; and he gave me a slap on the shoulder to signify that he understood me, and answered: 'I am glad, Odaq, for what you have said; but it is not necessary. To-morrow we will turn. You see, Odaq, neither have I any desire to die now, for another time I shall reach the goal which I must now give up.'"

This little incident seems to me to characterize equally well Peary and the young bear-hunter, who was not afraid to sacrifice his life for his master's kingly aspirations.

Otherwise the tales one hears are not entirely of a serious nature, and nothing has been more entertaining to me during the many days of bad weather, both in winter and summer, than sitting listening to the Eskimos' tales of privation and danger, tales which now, when gone through in memory, always end in sheer fun.

"Oh, well, that was when we were forced to eat our dogs raw, far from land, right out on the ice, while our enormous stores of meat were rotting at home in our camps." Little finishing remarks like these contain all their wanton self-mockery; for to an Eskimo it will always seem monstrously funny that one can let oneself be coaxed into leaving land, and go out into the cold pressure-ice of the Polar Sea, just for the sake of hewing one's ways through it, with death hovering above one in the enormous, white, lifeless desert.

It is very significant of the open-air spirit of the Eskimos, and of the mind of the hunter and his obstinate ambition, that a man who could look upon his suffering through a toilsome voyage as something sensational, would immediately be made a laughing-stock among his countrymen. When one has decided on the hazards of a journey, one must take everything that occurs like a man—that is, with a broad grin. I have even heard old Eskimos tell of situations wherein they were in danger of death, in such a manner that the audience knotted themselves with laughter.

It may be that in this matter we highly civilized, cultured beings meet a quality in the so-called primitive natives—whom otherwise we honour with all our gracious superiority—a mysterious and humorous contempt of death which almost makes the ideas danger and death merge into one. For instance, consider the way in which some families, which during Peary's last expedition but one had remained behind near the big lakes at the back of Fort Conger, managed to make their way home all the distance down to the Cape York district. The men, some with a team of two, some of three, dogs, without provision for the journey, brought their wives and children the hundred miles' long journey southward, first across the Kennedy channel to the land, continually hunting for food like beasts of prey as they travelled. Some of the women had newborn babes in the bags on their back, others were in an advanced stage of pregnancy, whilst others, again, gave birth to their children as they travelled the toilsome, dangerous way, advancing foot by foot, pushing and pulling the sledges along down to their homes. And they arrived quite unmoved by the fight for existence, bubbling with merriment as never before, everyone from the oldest down to the youngest babe strutting with health.

Anyone looking at the map will understand the magnificence of this deed. The hunters' sagacity and the constitution of the Eskimo race achieved in this undertaking one of their most glorious triumphs; it is a leaf out of the history of Polar travelling which ought to be known by everyone, even by those to whom the North Pole is only a name.

It was in the year 1907. At that time I came from Ellesmere Land with two Eskimos, when outside Cape Inglefield we ran across sledge tracks which we did not for a moment doubt were due to the rearguard of Peary's great army of offence against the North Pole. Their probable fate had been the subject of discussion among the tribe throughout the winter. We were confronted by two tracks—one from a team of four dogs, the other from a team of two. And it was obvious that the dogs must have been quite exhausted, for none of the travellers had been able to ride on the sledges. We saw the tracks of two men and two women; and, between these, the tiny imprints of children's feet—children of at most five or six years of age. The tracks came from Humboldt's Glacier and pointed downward to Etah.

"Look, the little ones have walked that long, long way," said one of the Eskimos when he saw the children's tracks.

"Our women bear strong children!" cried the other one, examining the tracks as he ran.

We decided to turn at once and make for the camp at Anoritoq, as there was a possibility of others being on the way and in the vicinity. It was impossible to tell what these people might have suffered and in what condition they might be. In great excitement we reached our destination. No one was there. Then we drove back again and on to Etah, and there at last we found them: two families, Odaq with his wife, a little son of five years, and a baby-in-arms; Agpalinguaq with his wife, a small daughter, and an almost new-born babe.

These Arctic travellers all looked like people who are returning from a little pleasure trip, well fed and smilingly healthy. The women and the little ones had just finished a walking tour of a hundred miles, the mothers with their smallest children on their backs, and all of them had for more than a month been a prey to the cold and the sweeping blizzards out on the ice. And if a blast is to be found anywhere in Greenland you will find it by Humboldt's Glacier—a blast with a bite in it. Another eight families were still on the way; two sledges had dropped a little behind the others, delayed because the women that accompanied them gave birth to their children whilst travelling. They told us in this manner, quietly and as a matter of fact, without any attempt to be sensational.

But never in my life as an Arctic traveller have I felt smaller than when faced by these child-bearing women, who with babes at their breasts undertook journeys which might have cost many a white man his life.

The harsh conditions of nature which force the Eskimos into an unending fight for existence, quickly teach him to take hold of life with a practical grip—i.e., in order to live I must first of all have food! And as he finds himself in the happy position that his form of livelihood—hunting—is also his supreme passion, one is justified in saying that he leads a happy life, content with the portion that fate has allotted to him. He is born with the qualities necessary for the winning of his livelihood, and the skill in handling the tools, which later on makes a master of him, he acquires through play while he grows up. On the day when he can measure his strength with that of the men, he takes a wife and enters the ranks of the hunters.

The sledge and the kayak now become the main factors on which his subsistence depends. But whereas the sledge is used for all kinds of hunting during the ten months of the year, the severity of the climate makes the use of the kayak possible only during a very short period; for the summer only lasts from the end of July until the first days of September.

As a rower of the kayak the Polar Eskimo cannot compete with his kinsman from South Greenland. His kayak is large and clumsy, and cannot stand a rough sea, for in its equipment it lacks both the half-jacket and the whole-jacket which covers the manhole; it is therefore unable to set out in all kinds of weather without danger of foundering.

The ocean is, however, generally full of ice-floes which calm the waves, and there is not very often a chance of rowing in a high sea.

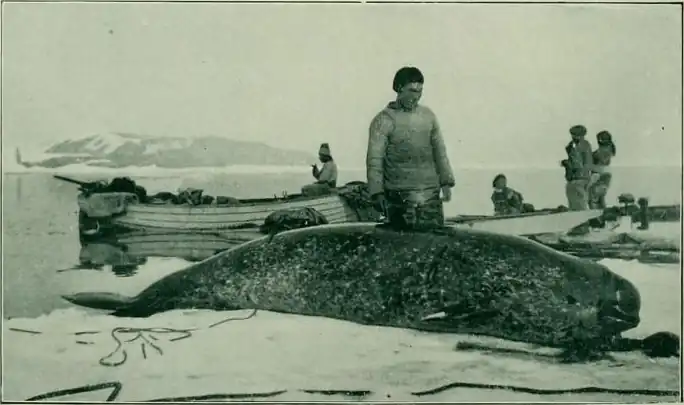

The chief weapon of the kayak is the harpoon with its line and bladder. What the craft lacks in seaworthiness is compensated for by the astounding skill with which the Polar Eskimo gets near to his prey, so that with ease and without the aid of a throwing-stick he harpoons his prey at quite close range.

The animals hunted from a kayak are walrus, narwhal, white-whale, bearded-seal (Phoca barbata), and ordinary fjord-seal.

Besides hunting on the sea, there is also extensive bird-hunting. The whole coast, from Cape Melville up to Etah, is with very rare intervals the breeding-ground of millions of Sea-kings, which herd together in such great numbers that they are easily caught in ketches from hiding-places between the stones.

The Sea-kings are small birds of the auk family, about the size of a starling; they generally live on mountains which go right out into the sea, and here they gather like an enormous floating raft, diving and tumbling after having made those little trips which provide them with food. Their breeding-places lie on the even slope of the mountains, where they make all stone-heaps alive. They sit in close flocks, covering the stones, and their tuneful chirping and merry whistling merge into one mighty tone which makes the whole landscape resound. And when all these flocks do occasionally lift and shoot up into the air, they sweep over land and sea like a tempest.

This little bird plays an important part in the household economy of the Eskimos, as everybody with a little energy can collect here a winter-store which will last all through the Polar night; and the soft little skins can be made into underclothing which, worn next to the skin, is warm and comfortable.

Besides the Sea-kings mountains there are three big auk-mountains—two by Parker Snow Bay and one by Saunders Island. Great flocks of auks, gulls, black guillemots, and fulmars hover round the shelves of the steep fells, and the meaty auk particularly is caught here by the hundreds in ketchers and put away for the dark period (October 1 to February 1).

Finally, in certain districts, the eider-duck gives its welcome contribution to the household stores of summer and autumn.

The great abundance of Sea-kings mentioned above is also put to good account in other ways, as these birds attract many blue foxes which find their food on the breeding-ground, not merely in summer but during a great part of the winter as well; for the wise fox thinks not only of to-day: he also collects his store for the winter, especially during the egg-laying season and before the young are able to fly. During visits to the mountains it is not unusual to see a fox coming along very carefully with eggs in his mouth, and by following him one may discover quite considerable depots covered with moss and turf.

These foxes were previously caught in native traps, of which several different types existed; but now they are caught in American steel traps.

After this survey of the chances which the summer offers, I will give a corresponding summary of the winter's hunting.

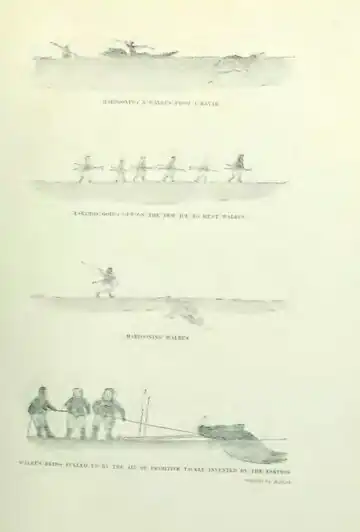

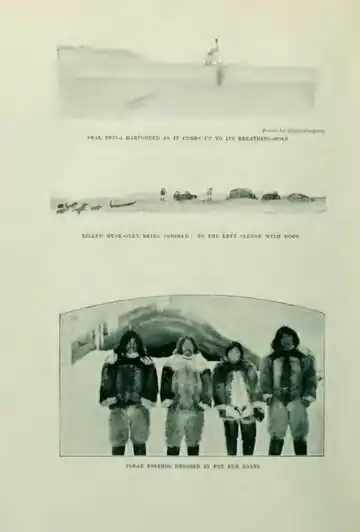

Already by the end of September the ice lies on fjord and bay, and in October hunting on the ice begins. If the ice lies shiny and uncovered by snow for a period, a rich hunt of seals takes place. The hunter ties a piece of bear-skin under his feet and moves along the ice quite noiselessly, occasionally stopping to listen, for in his approach to the seals he depends solely upon his sense of sound. When the seals come up to breathe through the holes in the ice, they blow so loudly that they can be heard a considerable distance. The hunter now moves towards the sound, taking great care to move only when the seal breathes. When it ceases he also stops, as otherwise it would hear him. The seal as a rule remains by its breathing-hole for some time in order to store as much air as possible in its lungs before diving into the deeps again, and thus, by taking advantage of the seal's respiration, the hunter is enabled to get right up to the hole. He then harpoons it with the greatest skill through an orifice which is so small that it barely allows the harpoon to pass through. It is obvious that the aim must be a sure one. But the senses of the Eskimo are so keen that even at night he is able to spot his prey and kill it by moonlight.

This way of catching the fjord-seal and the bearded-seal yields not only a rich catch in a short time, but is also considered the most amusing of all branches of hunting-sport.

In several places walrus is caught on the new ice, and in this case it does not matter whether snow has fallen, as these big animals are not so sensitive as the seals.

In November the ice between Saunders and Westenholme islands is so thin as to allow the walrus to shove its skull through it when, during its meal of mussels, it wants to breathe. The Eskimos then sneak towards it while it breathes, and no sooner is it harpooned than the line with lightning speed is fixed in the ice; the walrus is now tethered, and being therefore forced to return to the same breathing-hole every time it draws a breath, it is killed with lances.

In the autumn the walrus is fat and meaty, and the yield of the catch therefore goes much farther than that of the little seals. And this has its importance in a household where practically every means of finding a livelihood must be abandoned for the better part of the winter, and where must be fed not only the people, but also the sledge-dogs, of which a single man may possess over a score.

The type of hunting which the Eskimo values above all others, however, is the bear-hunt. I put once the following question to an elderly man:

Tell me what you consider the greatest happiness of your life."

And he replied:

"To run across fresh bear-tracks and be ahead of all other sledges."

Scarcely has the sun and the light returned when all men, who possess meat enough to leave their wives and children alone at home, go out bear-hunting, often for months, defying cold and all sorts of weather, welcoming snowdrifts as their camps. The southern borders of these bear-hunts stretch right down to Cape Holm, while northward Humboldt's Glacier is often passed. Finally, many of them cross over Smith Sound from Anoritoq to Pim Island, and follow the coast of Ellesmere Land almost as far down as Jones Sound. One has seen on these bear-hunts old men with white hair, men who during their life of hunting good and bad have experienced everything nature could offer them, hunters who have long ago forgotten the tally of their deeds; and young men, half-grown lads—all of them go crazy with the hunting-fever as soon as there is a chance of challenging the white king of the Polar waste. And for one single harpoon duel all the resultless and evil toil which preceded this supreme moment is forgotten.

The track of a bear, and far in the distance a small yellow blot on the whiteness; and then the good bear-dogs which fly across the ice like a tempest, out-distancing all the rest! This is one of the culminating points in life which every young Polar Eskimo dreams about.

From May until the middle of July is the period during which the seals crawl up on the ice to sun themselves and laze about in spring drowsiness. Then the Eskimos creep up close and harpoon them before they can pull themselves sufficiently together to wake up and slide down under the ice through the breathing-holes. If, however, it so happens that the sleep is light and the animal wakes up, every hunter knows to such perfection the art of imitating the sounds and movements of the seal that the animal imagines it sees a comrade lying there, happy in the warmth, and brushing its coat on the snow. The Eskimo continues his tricky advance, and the alarmed seal soon. lies down again, to continue the sleep from which it will never awake.

Previously only harpoon and line were employed in this work, but now the rifle, and the stalking-sail which has been imported from the South of Greenland, are used. This stalking-sail consists of a cloth of white skirting, large enough to cover a creeping man; it is fixed to a small sledge which the man, lying on his stomach, can push in front of him together with the gun until he is within shooting distance.

The Utut-hunting, as they call the method described above, gives the foundation for the very important winter-stores, which during the dark period free them from cares.

Of the land game, the reindeer was of great importance before the time of the Peary Expeditions, not only because of their meat, but also for the sake of their skins. These were used both for coats and for bedding. Unfortunately the surrounding land is not extensive, and the Eskimos had not for long been possessors of American magazine-guns when the whole stock was exterminated. At present one very rarely sees a reindeer.

Hares, on the contrary, are plentiful in some districts. The flesh is considered a tit-bit, and the skins are indispensable as stocking-skins. They are easily hunted both with gun and snare.

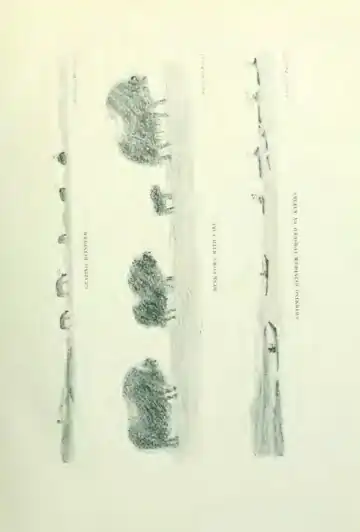

An animal which does not exist inside the Polar Eskimo's own territory, but which, nevertheless, within the latter years has played an important part, is the musk-ox. Everywhere along the stretches from Humboldt's Glacier down to the quite narrow strips of land among the mountains of Cape York, one finds their bones, but no person now living can give any information about the time when the last musk-ox here was slain.

As long as there were sufficient reindeer the skin of the musk-ox was rejected for bedding, being awkward to use and difficult to keep clean because of the long hairs; even now bearskins are preferred, and are looked upon as the finest, most durable, and most convenient. Unfortunately, everybody is not a great bear-hunter, so that the musk-ox is on the point of being considered entirely acceptable.

Every year in April and May great hunting expeditions for musk-ox are arranged, preferably through Ellesmere Land to Heiberg Land. These expeditions often last for a couple of months, as the Eskimos camp on the killing-grounds in order to dry the skins. As there is an average of a score of hunters each season, it would scarcely be too high to estimate that about three hundred musk-oxen yearly must bite the dust. It is deplorable that the Eskimo's lack of sense for limitation threatens this big game with extinction; but the danger is not an immediate one, as certain flocks in these regions number upwards of two hundred animals, which make a big mountain look quite alive—an impressive sight never to be forgotten by one who has seen it.

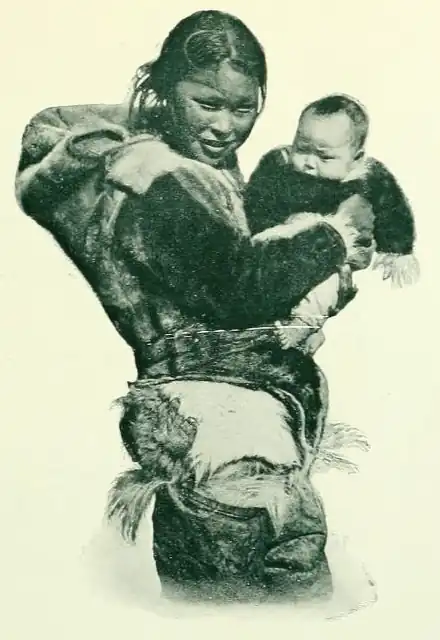

The Polar Eskimo begins and ends his life travelling. Already as a new-born babe he follows in the bag on his mother's back; nobody considers the time of the year, and oft-times the whimpering child is transported across wild glaciers in darkness and cold, ending the toilsome day in a cold, newly erected hut of snow. No wonder that he, or she, frequently becomes crooked with rheumatism at an early age and has to give up. This rheumatism is a legacy of all those days spent in snowdrifts during sudden blizzards, and serves as a reminder of the many times when he was taken unawares by storms during the hunting of reindeer and birds, and for weeks had to put up with a damp and clammy cave in the mountain.

Against this background, it is easy to understand that nobody has paid so much attention as have these people to the convenience of clothing. The climate of their country demands it, and it is an absolute condition that the hunter must be clothed fittingly. So the task of the woman is to make and mend the man's clothes, no less than it is to get the daily food. It is not without reason that the Polar Eskimo says that a man, as hunter, is what his wife makes of him. But the wife also knows how highly her part is valued by the man, and no praise is more flattering to her than admiration of her work. As luck will have it, she also has at her disposal the animals which yield. the warmest fur from which to make her clothes. Next to the skin is worn a light and soft shirt, made out of birds' skins, the feathers turned inwards; on top of this a coat of sealskin, with the hairs turned out, is worn during spring, summer, and autumn; in winter-time this so-called Netseq is exchanged for a coat of blue fox, also with the hairs turned out; and certainly this is the lightest and warmest costume in existence. For trousers the men use bear-skins—a kind of knickerbockers that reach just below the knees. Out of beautiful white frost-bleached sealskins without hairs they make boots and line them with hare-skin. For long sledge journeys they also use long-haired boots made from the skin of the forelegs of the bear, or from the leg-skins of the reindeer. A woman's costume is not much different from a man's. The chief difference consists in the trousers being shorter than the man's and made out of foxes' skin; the boots are almost as long as the legs. The difference in coats is only marked by a variation in pattern, or by the way in which skins of different hues are put together. The fox furs are seldom brought into the house, but are kept outside in a small stone cave. Thus the somewhat delicate skins are not exposed to the frequent changes in temperature, which would rapidly ruin them. The house-dress worn in the very warm houses and tents is reduced to boots and trousers, the upper part of the body being naked—a negligée costume free of all coquetry, as up in the bunk often twenty degrees (Cent.) of warmth is registered, whilst on the floor you will find Zero or a few degrees of frost.

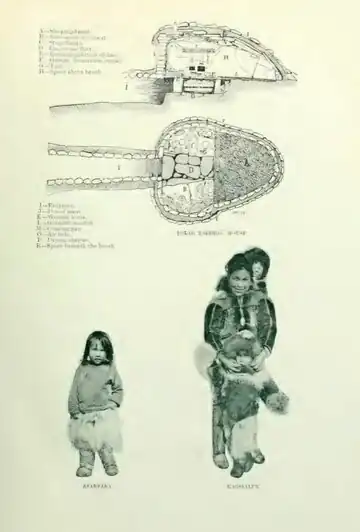

In winter the habitations consist of little houses, built of large flat stones and with domed roofs which, with great architectural cunning, are built so that the stones carry themselves without support. The houses as a rule are only planned for one family. A low and very long passage serves as entrance, and through this one creeps into the living-room itself, entering from below through a narrow opening. In spite of the primitive arrangement and the cramped space, the impression given by these huts is often one of extraordinary cosiness, the walls being covered with light-coloured sealskins. The stone sleeping-bench, which occupies the better part of the room, is always covered with a thick layer of fragrant hay, and on top of this a rug of bear-skin or reindeer. Light and warmth are supplied by two or three train-oil lamps, made out of the same kind of stone as that which forms the walls; with their long wicks of moss these lamps generate a heat fitting to the Adam's costume which is the house-dress. The bench is seldom larger than to allow four people to sit next to each other, and the roof is so low that one can rarely stand erect. Right opposite to the entrance there is a window of gut skins stitched together. In the middle of this window there is always a small, round peep-hole. In the roof there is another hole, called the "nose" of the house, through which the bad air is carried away.

Beside the permanent stone winter-house, there is also a snow-house. The big blocks of snow which constitute the material of this house are cut out of the hard drifts of snow with long knives. These snow-houses are built with great ingenuity. The inside arrangement corresponds to that of the stone houses, skins covering walls and roof. No block-house in the world can compete with a well-built snow-house as regards warmth.

The short summer is the time of the bracing life in the tents; here also we meet with the roomy stone bench which, with all its paraphernalia, makes a delicious resting-place for the night. The skin tents consist of two layers of sealskins on top of each other; they can therefore with ease resist the rain under all conditions. Here also are burning blubber lamps which give to the tent such a temperature that one can live in it until, by the end of September, winter supersedes autumn.

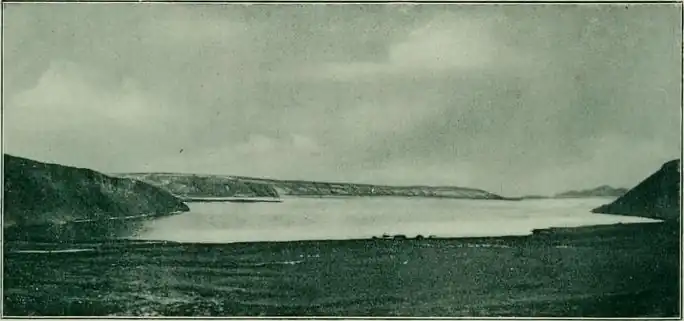

The permanent camps reach from Cape Seddon in Melville Bay right up to Humboldt's Glacier. As the tribe consists of so few individuals, there is plenty of elbow room for the hunters, and at the same time the game is given an excellent chance of renewal and breeding. For this little handful of hunters is distributed over a stretch of 800 kilometres.

The Polar Eskimos themselves classify their places of habitation according to the wind in the following districts:

- Nigerdlit Those who live nearest to the south-west wind.

- Akunarmiut: Those who live between the winds.

- Orqordlit: Those who live in the lee of the south-west wind.

- Avangnardlit Those who live next to the north wind.

By Nigeq they do not mean merely the south-west wind itself. Here is included also the mild Föhn-wind, which comes from the inland-ice with great suddenness and in an instant produces a positive temperature in the middle of the coldest winter. I will give an example:

Once, at the end of January, after a journey across Melville Bay, we drove in a party of twenty sledges along the land south of the Petowik Glacier on our way to Thule. The weather was good, and as the day's journey consequently had been a very long one, I felt somewhat tired and stretched myself on the sledge to take a little nap, whilst a boy who accompanied me drove the dogs. Just before my eyes closed I noticed a swirl above some cloughs near the inland-ice, but as there were no other signs of bad weather on the sky, none of us paid any particular attention to it.

My doze could not have lasted more than five minutes when I was awakened in the most brutal manner, being, as by a mighty grip, lifted up from the sledge and flung out on the ice. I received so violent a blow in the back that I was unable to get up for a moment, but when at last I succeeded in rising to my knees, I saw that all the many sledges which a moment ago had driven in a long string one behind the other, were swept together into one huge pile, like wooden shavings blown together by a breath of wind. With such suddenness and force the Föhn-wind had sent out its first squalls as forerunners of the storm which was coming. As it was quite impossible to stand upright, not to mention driving, we let ourselves be blown up on land with sledges and dogs, until we found some little shelter in a clough by a broad tongue of ice where the sledges could be anchored and the dogs tethered. Hardly was this done when the Föhn, with the roar of a hurricane, swept down upon us from the mountains and the inland-ice and made us suspect that the world itself was going under. It pressed its enormous weight down on the thick winter ice with such violence that the waves immediately burst up through the belt of the tidal waters. Half an hour later we saw through the darkness huge fissures in the ice, frothing white, and a few hours after the outbreak there was open sea where shortly before we had driven our sledges.

Altogether, one can understand the important rôle played by the wind in the lives of a hunting people whose subsistence depends entirely upon the sea.

The south-west wind decides the fate of the summer; for if it blows too frequently Melville Bay and all the north-west coast is filled with pack-ice, which gives rise to raw weather and poor hunting. The only beneficent act performed by this wind is in the autumn, when it not only makes the ice settle early, but also carries a lot of ice-bears on flakes from Baffin Bay in towards the land.

All camps from Cape York southward range under Nigerdlit. The mainstay in these places is the seal, but first of all it is the many bears in Melville Bay which lure people up here.

The Cape York district has no real summer; if now and then one crosses a glacier, winter hunting is possible all through the twelve months of the year. The scarcity of open water is responsible for poor hunting with kayaks and small winter-stores. The little Sea-kings are therefore a boon; and they are found in millions in the mountains hereabout. For the winter-store they are preserved in a peculiar way. During May and June they are pickled whole, feathers and all, in big, newly-flayed sealskins stripped whole from the seal, so that only a small opening remains near head and back flappers, and this can easily be drawn together. As soon as this skin is filled it is covered securely with stones so that the rays of the sun cannot reach it, as this would give the meat a bitter taste. The birds now slightly decay, and at the same time the blubber from the skin permeates the flesh. This dish, which is looked upon as an extraordinarily delicate morsel, is offered to all guests during winter as the best thing one can give to friends.

Even if there is some lack of meat here, there are other things which, according to the opinion of the inhabitants of the south-west, make this district preferable.

There is an abundance of blue fox, so that the people here, besides being able to procure pelts to excess, also have many "sale-foxes" for disposal. Then there are the bear-skins, which give warm trousers and lovely rugs for the bunks, and bring in some cash as well. The inhabitants glory in exciting hunting experiences all the year round, and to meet a Cape Yorker is nearly always to be counted as an adventure.

All this imparts to them a certain nimbus; but people from the sheltered side, who do not wish to seem inferior, will as a rule only admit that the Cape Yorkers may have the best clothes and the warmest bunk-rugs in all the district, "but," they add, "their houses are cold, for they have only seal-blubber to put into their lamps; their dogs are lean and have ugly pelts because they are not fed on the meat of the walrus and narwhal; and finally, in spite of all their cleverness, they are very fond of coming up to our well-filled meat stores to feed up their dogs, and themselves eat their fill in Mataq when, during the dark period, short commons is the order of the day."

Akunarmiut comprises the district round the present Thule. The chief means of livelihood here is the hunting of walrus, but seals and narwhals as well are killed in abundance.

It is of the utmost importance for subsistence here that the ice between Saunders Island and Dalrymple Rock settles evenly in the end of October and the beginning of November; for then the walrus remain for a long period by their breathing-holes, which they break with their skulls.

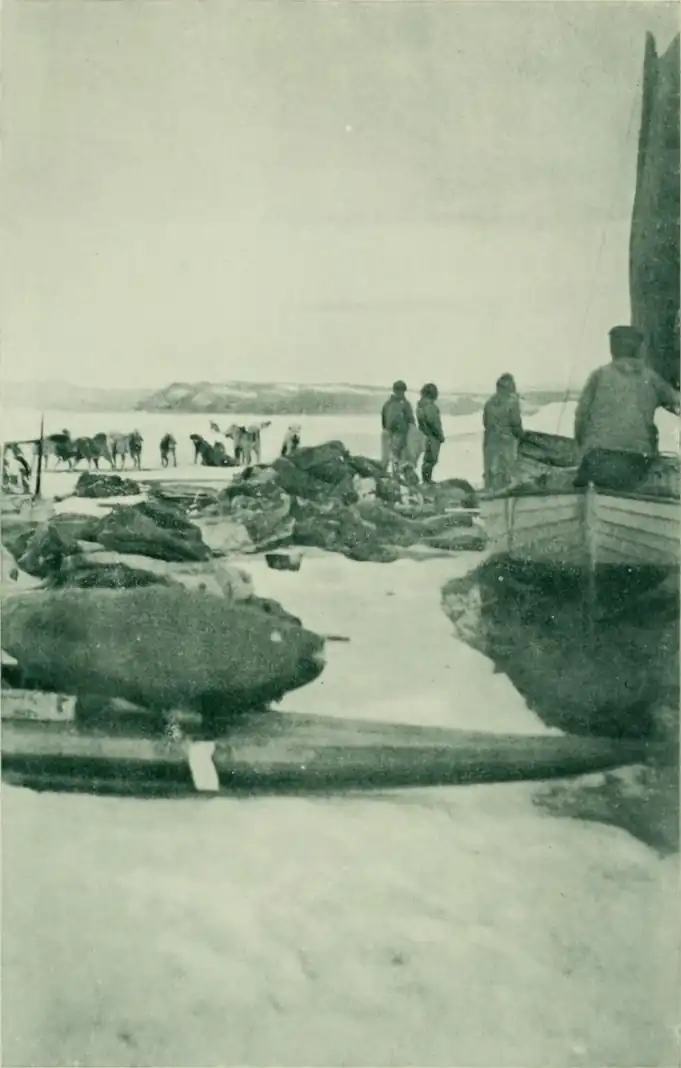

This hunting season is a beautiful and exciting time, with races from morning till night. The point is to be the first one with the sledge on the hunting-grounds, wherefore one may see, early in the morning, or rather in the night, one sledge after another shoot across the ice like a swift bird flying out into darkness. It would not do to make up large parties, as this gives small shares of the catch, so one spreads out as much as possible; and in the white darkness are discerned the contours of many fur-clad hunters distributed along the ice, with harpoon and line under their arms ready to take their chances. When a walrus has been harpooned, one sees the many bear-trousered, faun-like figures rushing up, joyful in the capture, to take their share in the division of the catch. The heavy animal is pulled up on the ice without difficulty by the aid of primitive tackle fixed in the ice.

Unfortunately this hunting of walrus often fails, and this district is therefore not reckoned as a good food-provider.

Orqordlit, or the lee-side inhabitants, encompass the whole district around the great Inglefield Gulf. Many camps are to be found here, where the hunting conditions everywhere are so brilliant that meat is always to be had in superfluity. In the mouth of the fjord there is an excellent run of walrus all through the summer, on the new ice in the autumn, and during the light time in March. When frozen sea, after being opened by a storm, freezes again, hunting like that described above takes place here.

Besides walrus, there is also a large and persistent shoaling of narwhal and white-whale, which are hunted from kayaks. These large, meaty animals provide substantial winter depots for the lee-side inhabitants.

The rich blubber from narwhal and white-whale yields, as is well known, far more light and warmth than that from seal and walrus, and these districts are justified in boasting of the fact that they possess the largest and warmest houses. Their kennels are abundantly stocked, and the dogs are fat with shiny coats. Foxes, however, are scarce in some districts, and the Sea-king is only to be found near Kiatak, Igdluluarssuit, and Neqe. But the climate during the autumn is far drier here than farther southward, and one can practically always reckon on a long ice-hunting period which goes to swell the meat stores still further.

The only thing really scarce is bear-skin, which is rightly considered indispensable. Without warm bear-skin trousers it would be impossible to undertake long journeys in winter-time, and where there is no bear-hunting there will be no proper bunk-rugs to lie on either. The hunters on the windward side therefore characterize the lee-side inhabitants, with some malice, as kitchen-hunters who, in spite of their wealth of meat and their fat dogs, have to trade for bear-skin with the real hunters.

Avangnardlit, or those who live next to the north wind, includes the camps of Etah and Anoritoq. The conditions at Etah are excellent for walrus hunting, and at the same time this spot is one huge singing mountain where the Sea-kings live. These are not to be found by Anoritoq, but as compensation there are there, besides walrus, excellent drives of narwhal. Wherever these are killed they put their stamp on the indoor life of the winter. In both places there is excellent bear-hunting to the north and west, and conditions of life here correspond in every way to those in the south-west. There is wind in abundance, not from the south-west, but from north and north-east, and it often blows with enormous violence. Contrary to the south-west wind, however, it sweeps the coast clean of snow, and is therefore the wind one especially hopes for at the time when the ships are expected.

We have now dealt with camps within the district, but one must not regard the Polar Eskimos as fixed settlers, for in all the world one can scarcely find a people who lead a more nomadic life. The stone houses built by ancestors long forgotten merely stand along the coast; for, as the material is stone, the tooth of time does not tear them. It requires only a minor reparation before a stranger may move into such a house when it has been aired all through spring and summer.

No Polar Eskimo will live for more than a year or two in one place; then his longing to get into new conditions and to hunt on new ground awakes. With every spring comes the wander-lust, and when Nature itself shakes the yoke of winter from its shoulders the desire arises to strike camp and follow the many birds of migration which herald summer's arrival.

The removal is in reality nothing but a change of houses on a grand scale. Just as nobody owns the seal in the sea and the reindeer on land, so it follows that nobody has a right to possess a house. When Pualuna moves out of it to seek another place it is no longer his, and if Maja chooses this place of abode he may quite calmly move in.

All the excitement that accompanies the decision that must be taken nearly every spring as to where one intends to hunt the following winter, and all the merry moods of camp-striking which seize on everybody, find their expression in a shout of liberation resounding through the whole country which, for many months, has been bound in cold and darkness.

It generally happens that those who live on the south-west side, or nearest to the north wind, move to the lee-side camps to spend a couple of years in abundance, in peace and quietness acquiring new dogs. Many a confirmed lee-side inhabitant will go northward or southward in order to find bunk-rugs and blazing white bear trousers. Thus these peoples' lives are based on an ingenious training for the finding of a means of livelihood, a training so well adapted to meet the demands of their harsh country that the civilization built upon it makes of the Polar Eskimos the most care-free people in the world. Nowhere else can one live, as one does here, in such a state of practical and simple communism which gives equal rights and equal chances to everybody. One has tried to counter-balance even the fickleness of fortune by dividing all the larger animals into pieces which are distributed to everybody who, during the hunt, has not had the luck to be the first to harpoon, say, a narwhal. By this distributive arrangement every hunter is entitled to meat if only he will keep in the vicinity of the one who kills the quarry. This seems to be the result of humane sentiments developed during the fight for existence against niggard Nature.

There is yet another point. Men are not all born equally strong and supple, and it is generally only a select few who are able to avail themselves of the chance to throw the first harpoon into an unwounded animal. But if once the animal has got the huge bladder with its heavy trailer dragging behind it through the water, even the mediocre hunter can take part in the kill. It is for this work that he receives his just and generous part of the booty. For the maintaining of one's position as a breadwinner in this community one thing only is required—this is industriousness. The lazy man who will not take up his share of the work must go his own way.

Is it possible in any community to get closer to the ideal than this, that the only reason for poverty is laziness?

The Eskimos thus live merrily together, treating their women and children kindly; and the families are bound to each other with bonds of affection, often manifested in a striking manner.

It would not be possible to finish even the shortest sketch of the Polar Eskimos without briefly mentioning their peculiar and primitive views of life.

The Polar Eskimos do not believe in a God to whom one must pray, but they have as a foundation for their religious ideas a series of epic myths and traditional conventions, which are considered an inheritance from the very oldest time. In these their ancestors laid down all their wealth of experience, so that those who came after might not make the same mistakes and harbour the same erroneous notions as did they themselves.

The myths, which are handed down from generation to generation by the oldest to the youngest within the community, are to be looked upon as the saga of the Inuit people. These myths are partly simple narratives, partly a warning against those who will not submit to the demands of tradition, and for the rest they are tales of heroes who in every possible danger acquitted themselves in such a way that they are held up as glorious examples for coming generations.

Osarqaq, a wise and intelligent man, once defined to me their own conception in the following words: "Our tales are narratives of human experience, and therefore they do not always tell of beautiful things. But one cannot both embellish a tale to please the hearer and at the same time keep to the truth. The tongue should be the echo of that which must be told, and it cannot be adapted according to the moods and the tastes of man. The word of the new-born is not to be trusted, but the experiences of the ancients contain truth. Therefore, when we tell our myths, we do not speak for ourselves; it is the wisdom of the fathers which speaks through us."

As an example of these myths, I will recount one which relates of "the time long, long ago when man was created." With its grotesque forcefulness and deep originality it serves as a good example of Eskimo imagination. I translate it here as literally as possible from the dictation of an old Eskimo woman called Arnaruluk.

"Our ancestors often spoke about the creation of earth and man in the time of long, long ago. They did not understand how to hide words in written signs like you do; they could only speak, the men that lived before us. They spoke about many things, and therefore we are not ignorant in these matters which we have heard mentioned time after time ever since we were little ones.

"Old women do not carelessly waste words, therefore we believe them. Age does not tell lies.

"At that time, long, long ago, when earth was to be, it fell down from above; soil, mountains, and stones fell from the sky. Thus earth was.

"After earth was created came men. It is told that men came from the soil. Little children came out of the earth; they came forth between willows, covered with willow leaves. And they lay sprawling between the dwarf bushes with closed eyes, for they could not even crawl. The soil gave them their food.

"It is next told about a man and a woman. The woman makes children's clothes and wanders over the soil, where she finds little children; and she dresses them and brings them home.

"Thus two became many.

"And when they were many they wanted dogs. And a man went out with a dog's harness in his hand, stamping the ground whilst he called 'Hok—hok, hok!' Then the dogs poured forth from mounds, tiny mounds; and they shook themselves, for they were full of sand. Thus man got his dogs.

"But the men increased, they became more and more. They did not know death that time long, long ago; and they grew very old. At last they could walk no longer; they grew blind and had to lie down.

"Neither did they know the sun; they lived in darkness; day never dawned. Only in the houses had they light. They burned water in their lamps, for at that time water could burn. But the people who did not understand how to die became far too many; they overcrowded the earth—and then a mighty flood came. Many were drowned, and there were thus fewer people. On high mountain-tops where often we find mussels we see the traces of this flood.

"Now the people were fewer two old women began to talk. 'Let us be without day,' one of them said, 'if at the same time we may be without death!' I think she was afraid of death.

"'No,' said the other one, 'we will have both light and death.' And as the old woman had spoken these words so it came to pass.

"Light came, and joy and death.

"It is told that when the first man died the corpse was covered with stones. But the corpse returned—it did not understand quite how to die. It put its head up from the stones, wanting to get up. But an old woman pushed it back again.

"'We have sufficient to drag and our sledges are small,' she said.

"For they were on the point of breaking camp to go hunting. So the dead man had to return to his mound of stones.

"Now, when the people had light they were able to go out hunting, and were no longer forced to eat from the soil. And with death came the sun, the moon, and the stars.

"For when the people die they rise to the sky and become radiant."

The rules, which played an important part before the time of the mission, can be compared to a collection of unwritten laws which tell men what, under certain conditions, they must observe and conform to. As with most primitive peoples, these rules relate especially to birth and death.

All these rules of life, which, perhaps, seem unreasonable and childish to us, were maintained with much authority by the necromancers. These correspond to the medicine-men of other primitive peoples; they are in a position to act as middlemen between man and the powers that meddle with life. This they are able to do because they have knowledge of and intimacies with things which are hidden from ordinary mortals. Therefore, it is not everybody who may be a necromancer, for it is not everybody whom the spirits will serve. A man must have a vocation, and very special abilities are required, which are developed in the great loneliness of the mountains far away from people. Nature is imagined to be full of invisible beings with supernatural powers and abilities, the so-called Tornarssuit. But the necromancers have the power to subject these beings to their will to such an extent that they can employ them as "ministering spirits," which are invoked under the observance of secret ceremonies, preferably with extinguished lamps and to the accompaniment of a weird and gripping ghostly chant.

These necromancers are not frauds and charlatans, as one has so often been disposed to presume, but as children of their day they themselves have implicit faith in the seriousness of their mission. Their significance is based on the fact that the primitive religion lacks the worship of a deity; thus the weak and timid find a refuge with the one who understands how to master the mystic forces of Nature, forces easily offended and dangerous in wrath.

The following may serve as an example of the rules:

Those who have been engaged in burying the dead must keep quiet within their houses and tents for five days. During this period they must not prepare their own food or divide up the cooked meat. They must not take off their clothes during the night or push back from their heads the fur hoods. When the five days have elapsed they must carefully wash hands and body to rid themselves from the uncleanness which they have contracted from the dead. The Eskimos themselves give the following explanation of the reason for observing this rule:

"We are afraid of the big evil power which strikes down men with disease and other misfortunes. Men must do penitence because in the dead the sap is strong, and their power is without limit. We believe that, if we paid no attention to that over which we ourselves are not masters, huge avalanches of stones would come down and crush us, that enormous snowstorms would spring up to destroy us, and that the ocean would rise in huge waves whilst we were in our kayaks far out at sea." But one may also acquire additional strength through one's life and increased powers to resist danger, with good fortune in all matters of chance, by using amulets and magic formulæ.

The amulet is a protector against danger, and imparts to its owner certain qualities; under certain conditions it may even change him from man into the animal from which the substance of his amulet is derived. An amulet of a bear which was not slain by human hands renders the owner immune from wounds; a part of a falcon gives certainty in the kill; the raven makes one content with little; the fox imparts cunning. Often the Eskimos wear a Poroq of a stone from a fireplace, because this has been stronger than the fire; or they smear an old man's spittle round a child's mouth, or put some of his lice into a child's head, thus transferring the vital force of the old one to the young.

The magic formulæ are "old words, the inheritance of ancient time when the sap of man was strong and the tongues were powerful." They may also consist of apparently meaningless connected words dreamed by old men. They are handed down from generation to generation, and the single individual looks upon them as invaluable treasures which one must not give away until death draws near. They are impossible to translate, and would therefore be difficult to recount in this short summary, which merely purports to give what is absolutely necessary for the understanding of these strange people who will so often be mentioned in the following narrative.

Of the religious traditions of the Polar Eskimos I may mention, furthermore, that man is divided into a soul, a body, and a name.

The soul, which is immortal, exists outside the man and follows him as shadow follows sunshine. It is a spirit which looks exactly like a man. When the man is dead it rises to heaven or goes down into the sea, where it foregathers with the souls of the fathers. And both places are good to be in.

The body is the abode of the soul; it is mortal, as all misfortune and illness may strike it down. In death all that is evil remains in the body, wherefore one must observe the greatest care in dealing with the corpse.

The name also is a spirit to which a certain store of vital power and skill is attached. A man who is named after a deceased one inherits his qualities.

I commenced this chapter by stating that the Polar Eskimo does not know worship. Neither does he in the sense with which we are familiar from other religions; he is content to bow down to the Great Unknown, and he is not afraid of admitting that he knows nothing and that his belief is probably wrong. The admission of his limitations and his complete honesty are here, as on all other points, unfailing.

But even if worship is denied him through the simple religion which was handed down to him from his forefathers, he is not a stranger to devotion. And as I am writing this my thoughts return to the many men and women out there whom in the winter evenings I have seen quietly and silently wandering up to the graves of their dead. Here they may remain hour after hour in a mute devotion, which assuredly is no meaner expression of the feeling of human impotence than that which, amongst more highly cultured peoples, manifests itself in prayer and supplication.

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)