Greenland by the Polar Sea/Chapter 2

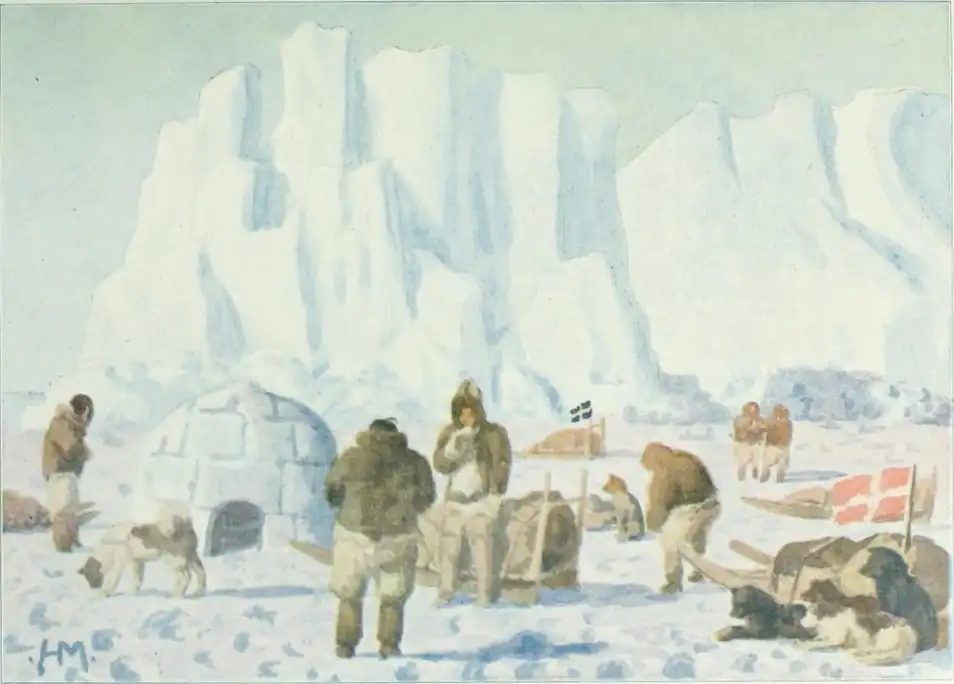

THE preparations for long journeys are made in a very serious spirit; but, as compensation, when the actual start is made and leave is taken of the camp, the mood changes to one of happy geniality, and one goes out to meet one's fate and adventures filled with joyful expectation. And thus it is now with us when at last the sledges are loaded and the dogs stand harnessed by the side of the old Danmark. By a strange coincidence, Mylius-Erichsen's old ship is to-day the background for our departure.

April 6th, 1917.—In celebration of our departure we were invited to breakfast on board, and the Eskimo members of the expedition and their wives were included in the party. Captain Hansen of the Danmark had done everything possible, and our appetites did justice to the luxuries of the table.

But the fever of travel had seized on us and we had in mind only the idea of getting away. Wulff and Koch had already set off, and were one day ahead of us. It had been necessary for me, after everything was clear, to spend the last night alone, so that once more I might go over all the lists and memoranda of those things which must not be forgotten. This, more than anything else, requires the peace of solitude, for there is the ever-present menace that if a single little thing is forgotten, it is impossible to procure it when one is hundreds of miles away from the depot, however urgently it may be needed. Probably most leaders of an expedition spend the last night before the start without sleep. All the keener is the feeling of relief and the appetite for work when at last everything is clear and ready for the journey.

The impatient dogs lie on the ice awaiting the signal for departure; whimpering and barking they strain at the traces, and a man is posted by each sledge so that no team may interfere with the right succession of events by forging ahead before the drivers are ready. Alas! when they are no longer in the vicinity of the permanent camp, where there is always plenty of blubbery walrus-hide to be had, this exaggerated joy of life will soon wane. This loud eagerness, this overflowing energy, will be damped all too soon when day after day they are offered many hours of monotonous toil on meagre rations. But to-day there is no limit to their wild, youthful courage, which bubbles over after the many days of rest and strong food. Everyone is in festive mood.

The weather is glorious, with a high sun above the white snow: the ice-mountains of the fjord gleam in the light and the basalt of the mountains out towards Cape Parry flash in merry colours.

The crew of the ship wander around examining with interest, and with the eyes of experts, the securely-roped sledges. Now and then they go out to stroke the dogs. The fuss of departure amongst these many sledges and all the busy people reminds one of the stir of a fair-ground.

When at length the start is made and the men have said their last word to the women who must remain behind, each man throws himself down on his sledge and races along the fjord for the first modest kilometres towards the point which we have set ourselves as the goal for the coming half-year. In an hour the Danmark is out of sight and the mount Umanaq, where lies the camp, is outlined as a small cone far, far away in the horizon behind us.

The dogs are in excellent condition and stretch out for dear life, and though the loads are heavy we hum along. Driving on the ice is easy, and the smooth iron runners of the sledges sing across the frozen snow. We started about four in the afternoon and already by two o'clock in the morning we have covered the first 94 miles to Netsilivik, where we meet our comrades.

April 7th.—Netsilivik is a little camp consisting of three houses, and it is only because of the big heart of the Eskimo that it is possible for us all to get a roof over our heads. We are fifteen men in each house, and for the first few hours everything is sheer confusion. The dogs are tethered on the ice outside. We make camp and cook a well-deserved cup of coffee on the humming Primus, whilst the dogs are fed from the abundant meat stores of Netsilivik.

A glance through the peep-holes of the small gut-skin windows shows that our comrades and all their friends still lie in the sweetest of slumbers. The heat in the overcrowded stone house is scorching, and I therefore decide to pay a morning call at Iterfiluk's house, which lies a quarter of an hour's walk away from the others. Iterfiluk is a gossiping widow of fifty years of age, and she is a great friend of mine. In the course of the winter she has often been to Thule to make boots for the members of the expedition, and she therefore receives me with a shrill shout of welcome as I crawl through the passage into the house; I am only discovered at the very moment when I crawl up on to her greasy stone floor. Her house also is filled with travellers, and while her visitors are asleep she herself sits stark naked by her lamp, like one of the holy virgins guarding the lamp so that the precious light shall not be extinguished during the night. For up here it is reckoned a great disgrace if the guests of the house should wake up in the cold with the lamps gone out.

According to the custom of the country I also must pull off my clothes and press in between Iterfiluk and one of her friends, the fat Kiajuk, who wears the same paradisaical costume as the hostess. I sit chatting with her for a long time, until tiredness and the atmosphere of the house rob me of all strength, so that I, as all the other guests have done, droop down and slip into unconsciousness.

However, we could only afford a few hours of sleep and then we had to push on. For when one has many dogs requiring food it is considered good manners to leave the camps early. By noon of the same day we had started for the camp of Ulugssat on Northumberland Island.

The camps in this district generally consist of from three to five little stone houses; consequently, when occasionally one comes to a place with ten or twelve houses an impression of crowdedness is created akin to that felt by the countryman when he visits the capital. Up here we are so accustomed to expect nothing out of the ordinary that an uncommonly large town like this quite overwhelms us. Along the fronts of the houses we see everywhere stagings built of snow-blocks, covered with lovely fresh walrus meat, flaming red against the white snow.

The dogs of the camp were all tethered in a row, team behind team, on the ice-foot, and they gave vent to savage yelps at our arrival. According to the old traditions, which demand of the visiting sledge parties a polite reserve, we all stopped on the sea-ice, some distance from the ice-foot. On land, the Eskimos were standing by the houses, looking down at us silently but interestedly. In accordance with the custom of the country, long minutes passed before both parties gave vent to their joy over the reunion.

At Ulugssat it was easy to find quarters, for our hosts vied with each other in their invitations to us. Before we went in to see to our own comfort, however, all teams which were to take part in the long journey were given a thoroughly good feed from the abundant meat stores of our hosts. This was really great extravagance, as ordinarily the dogs are only fed every second day. But one permits oneself such extravagances when one is going out on an expedition.

The houses of Ulugssat were of all dimensions. There was the big Tornge's palace, in which the interior was divided into two benches with a sleeping capacity for at least twenty—a comfortable room, entirely lined with wood, and festively illuminated by three brilliant train-oil lamps. Delicious meat and glossy narwhal skin were temptingly laid out on platforms of flat stones built for this purpose near the lamps. Such was the house of the greatest hunter; but there was also the den of old Simigaq, where the passage was so narrow that, in spite of honest attempts, I did not succeed in squeezing myself through to pay her a short call.

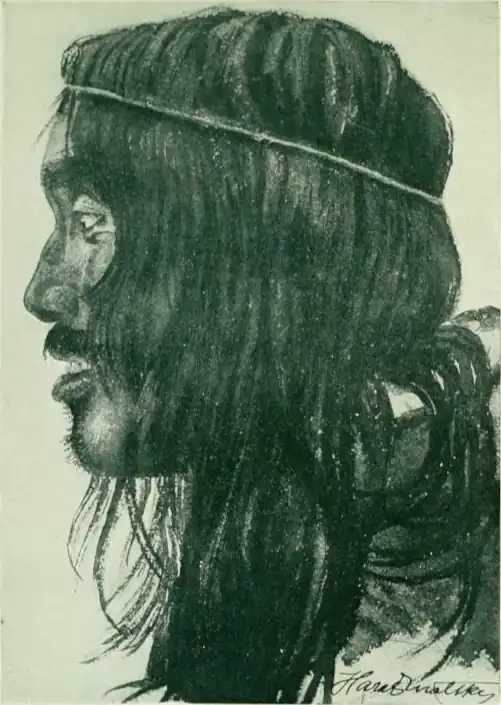

Simigaq, "The Corked-up One," is the oldest woman of the tribe. In a small way she still invokes the aid of the "ministering spirits" when fate, or the camp, seems to oppose her desires. Otherwise she is like a living book for all those who like to listen to old stories and myths. And Simigaq is never pressed in vain.

In Ulugssat the afternoon was passed in the buying in of meat for men and dogs; and we had a busy day of it as we ourselves had to be present everywhere. It is of importance to select the best flensing parts of the meat, preferably pieces where the skin is already separated from the flesh.

Furthermore, during the winter the women of the camp had been given commissions to make a lot of kamiks (shoes) and mittens, and these articles now had to be delivered, criticized, and paid for. In the midst of all this business which could not be delayed, we had to find time for all the unavoidable meat feasts given to celebrate our departure. Well meant as they were, we found them somewhat of a strain; fourteen meals of walrus meat in the course of one day is a considerable feat. It certainly eased the strain that the meat was served in different ways. Some of it was freshly boiled; some newly killed but frozen; some, again, decayed but frozen. This last sounds bad but tastes good. But this excessive hospitality made us all so heavy with food that we looked forward with longing to a night's rest.

In Ilanguaq, "The Little Companion's," house drum-songs were sung with great enthusiasm. I called, but I had to clear out quickly again as the heat was so excessive as to wet one through. Nevertheless, I was told next morning that the singers kept it up all night. As the population from the surrounding camps had poured in to bring me meat and accompany us on our way, there were many sledges about. Such an occasion for improvised musical feasts is greedily seized upon, and each one sings exclusively the drum-songs which he himself has composed.

Late in the evening, long after my housemates were asleep, I heard creaking footsteps in the frozen snow. A little later the door opened, and when she had carefully convinced herself that everybody else was asleep, old Simigaq entered and sat down by the head of my sleeping-place. It was her intention, she said, to make my sleep light. She wished to prepare my way towards the land of dreams with little sayings and legends; but first of all she wanted to give me for my journey the advice of an old woman, for she believed that age gives certain powers which one may hand on to the young. She felt herself in debt to me since last we met. I had once saved her and brought her to my home from a bird-mountain, where her not very courteous son-in-law had deposited her for the time being; now she wanted to pay that debt before I left. If it be true that age gives to old people's words a strength which can be transmitted to the young, old Simigaq was certainly a tremendous source of power. Not only was she the oldest woman in the tribe—red-eyed, toothless, baldheaded, crooked with rheumatism, nearly blind, and thus in possession of every scar which a long and hard life leaves-but, in addition to all this, she had now become so ugly and withered that they said she could not sink even if she were thrown into the sea. But in spite of this, the memory of the time when she was young, and her powers were directed to quite different ends, still lived fresh and merry in her consciousness.

She herself told that she had been the possessor of an extraordinarily fair complexion, and of thick hair which, like a waterfall, hung down about her naked body. She was also tall and deep-bosomed, and to all these charms was added a care-free and happy temperament. The men vied with each other in their efforts to win her favours, and her attractiveness resulted in several marriages. At last she had found a haven with a man called "The Little Throat"; she had been married to him for several years. But this was when the white men only fitfully visited "The Land of Men," and when guns and the other implements for the daily catch were unknown. The use of the kayak had been forgotten, and now one camped near the bird-mountains during the summer when the sea was open. It happened not infrequently that there was a famine during the winter, for one must gather many Sea-kings before one could lay in a store large enough to see one safely through the Polar night.

On one occasion, when there had been a poor hunt and everybody was hungry, "The Little Throat" suddenly disappeared from the stone hut. It was no longer good to be there. But, strangely enough, the whole stock of puppies disappeared at the same time, and this aroused Simigaq's suspicions. She went to the mountains and tracked down her man, who sat gorging himself on the puppies, which he had roasted on a flat stone.

The annoying part was not so much the fact that the puppies, which should have hauled their sledges on their journeys next spring, were killed, but rather the circumstance that "The Little Throat" had deceitfully eaten them alone, without asking his beautiful woman to share in the feast. Naturally this led to a divorce. Thus "The Corked-up One" had again passed from hand to hand for some time until she had married Kajok, called "The Yellow One," with whom she had lived happily until his death.

And now this weather-worn and hardened old woman, who had lived such a life of good and evil, was sitting at my head, wanting me to share the benefit of her experiences, the result of her long life. On a long journey it would be as well to be on good terms with the spirits that rule over mountains and abysses; the loneliness also had its powers, of which puny man must beware. Therefore she came to me this last night with a few magic songs.

Oh, she said, these magic songs were poor and insignificant, a collection of short, meaningless words. But what about that? After all, we humans understand so little of that which is met with in places where one is alone with the silent world.

This was her explanation and her excuse. And while, possessed like a pagan priestess, she mumbled her songs through her toothless gums, I lay close to her on my rug and listened.

Here is the song of life, the song for him who wishes to live:

She murmured the words to me, whispering and distant in her ecstasy, until they were as if burnt into my consciousness.

Then came the song sung by men who, driving heavily and slowly, are in danger of death:

If the game disappears, so that one must starve, the following is sung:

Thus a good catch is secured.

She chanted words which disperse the fog; the bear-song which lures forth the bear; the drinking song which procures water for the thirsty; and songs to be sung during the climbing of mountains—all of them useful and indispensable for him who travels to unknown countries.

The mountain-song was the last one I heard, then the monotonous voice overpowered me, and when I opened my eyes after a few hours' sleep, old Simigaq had long ago crept home to her modest den. I jumped down from the bench and peeped out through the window to look at the weather. It was light as day now, even in the middle of the night; the sky was clear, without a single cloud, rounding itself like a blue dome above the land and the white ice. A faint pink tinge announced that sunrise was not far away, but it was yet too early to break camp.

Next day, in brilliant sunshine, I drove on with Ajako to the camp of Igdluluarssuit, while all the other sledges went directly to Neqe. We still wanted a couple of pack-sledges and some more meat, and at Igdluluarssuit lived Sipsu, an excellent hunter and experienced sledge-driver, whom I would fain have with me on the last pack-sledge right up to Fort Conger.

April 9th.—The following day the sledges and all the meat procured at Neqe were collected. The heaped meat formed a considerable bulk, and we had twenty-seven sledges and 35+ dogs to transport it. This was rather a large apparatus to set moving for the sake of six sledges, and to understand it the following explanation is necessary:

As already mentioned, all our equipment was Eskimo throughout, as were also the provisions. Walrus meat is excellent food for the dogs, but it has the great drawback of containing 65-70 per cent. of water. This makes it very heavy for transport, and whilst one can reckon a pound of pemmican a day for each dog, one must reckon of walrus meat or skin about three pounds a day, or from five to six pounds every second day. And besides our own dogs we had, of course, to feed the teams of the pack-sledges as well.

We planned our journey so that altogether fifteen sledges were to go to Humboldt's Glacier, thirteen to Cape Constitution, eight to Thank God Harbour on Polaris Promontory, and by the time we arrived here the loads would be so reduced that the six sledges for the long voyage could take over everything.

The meat, ordered beforehand, lay ready for us on the icefoot. I had only to pay for it and then distribute the loads. The payment generally demanded consisted of powder, lead, and percussion caps. This part of the business was easily and quickly arranged. It is not difficult to come to an agreement with Eskimos with regard to provisions for a large expedition for an indefinite period. They fully sympathize in a matter like this. Greater difficulties arose in the distribution of the meat on the twenty-seven sledges; for here one had to consider not only the strength of the teams but also the quality of the sledges.

When everything was in order the motley train set out, and the eager dogs rushed across the ice to the accompaniment of screeching whip-lashes, soon to disappear behind the nearest headland. Our road for the first six miles lay across the frozen ocean as far as Cape Alexander, where the water is always open, even in the severest weather. This water we had to get round by driving up across the inland-ice.

We started at four o'clock, and the glacier where the ascent was to commence we reached at about seven in the evening. Here we all stopped and made the inevitable cup of coffee, the local cup that cheers. The passage does not take more than a couple of hours, but it is generally exceedingly hard work. First one toils up the steep slopes, dripping with perspiration; then, at a height of three hundred metres, comes the biting north wind which, in clear weather, always rages round the neck of Cape Alexander. The drifting snow is as thick here as an English fog, cold and damnable, and often so violent as to make it almost impossible for one who comes from the south to drive the dogs up against the wind. The habit of strengthening oneself with a cup of good, strong coffee is therefore not to be wondered at.

It was difficult to get the heavy sledges up the glacier, which is always blown hard and smooth; but as there were many of us to share the burden, the crossing was successfully accomplished. The storm and the drifting snow we accepted with a good temper, knowing that we would doubly appreciate the calm weather which always awaits the traveller on the frozen sea.

April 10th.—At four o'clock in the morning we arrived with all our train at Etah, where we camped on the ice just outside the headquarters of the Crockerland Expedition.

In spite of our early arrival, we had the heartiest reception from Captain Comer, who is always early up and about. He invited us into the house, where Mr. McMillan offered us breakfast, an invitation we could only accept a few hours later when our populous and elaborate camp was made.

For three days we were the guests of our American colleagues, and during that time we were shown every kindness. We had originally decided to spend only a day here, but bad weather forced us to prolong our visit.

During our stay Mr. McMillan kindly helped us with some pemmican and biscuits, an excellent supplement to our own stores.

April 11th-12th.—We spent the days at Etah killing time in various ways. We dived into the very extensive library of the Crockerland Expedition, visited the Eskimo families which were all old friends of ours, and every evening ended with a ball which lasted into the early hours of the morning.

The Americans had a wonderful gramophone, which entertained us greatly with its varied and select repertoire. There was something for everybody's taste, so that at times we heard songs from all the operas of the world, sung by Caruso, Alma Gluck, Adelina Patti, etc., and at other times we abandoned ourselves to musical debauches, for a change indulging in tangos and one-steps.

People at home who have access to real music, performed either by themselves or by professional artists, generally turn up their noses at our joy in the gramophone, which they regard as a musical disgrace. I do not consider that I am more unmusical than the average man, but I confess, nevertheless, that I am one of those who pay homage to the gramophone. Wherever I have met it, be it in a winter camp among the Eskimos or among the Danish families in the Greenland colonies, it always brought a peculiarly pathetic greeting from all that which we up here so keenly long for, but must forgo; and I have seen many a man, whom one could not otherwise accuse of sentimentality, forcibly subdue the emotion which the gramophone's music aroused.

The three days spent in involuntary idleness took a good slice out of our meat stores. But one day, as I was trying to make up my mind as to how much more we could permit ourselves to eat in case the storm should last, a man named Majaq appeared, and he rid my mind of all cares. He had spent spring and autumn by Renslaer Harbour and told me that he still possessed considerable meat stores there, which he put entirely at the disposal of the expedition if only we would pay him in ammunition; this offer we of course accepted with joy.

On the 13th of April, in the afternoon, the weather at last calmed down so that we could think of breaking up. There was still a gale, but as under all circumstances here in Etah wind and good weather go together, we made ready and drove up against the wind. Towards morning we reached Anoritoq and camped for the night.

By a freak of fate Anoritoq possesses a name which means "The Windswept One." This little camp, which has become world-famous as the winter quarters of Dr. Cook's pretended Polar Expedition, is, however, the only place in the neighbourhood of Etah which is always dead calm.

Anoritoq's name is derived from an old tale about a certain Anoritoq who reared a bear.

The woman Arnajaq tells the following:

Once there was a man named Angutdligamaq, who himself never hunted. He occasionally went out on the ice, and if he chanced to meet a man dragging a seal along, he killed him and took the seal home as his own catch. In this way he lived. His countrymen dared not rebel against him because he was so strong, and thus it came to pass that through many years he lived by murder and robbery. But one day they decided that he was going too far, so they agreed to defeat him with cunning. "Listen, Angutdligamaq," someone said, "you do not know what fun it is to go hunting with others; you ought to try it, I am sure you would then join us every day." When Angutdligamaq heard this he joined the hunters of the camp on the next day. But as he was quite unused to the life outside the houses he was very clumsy, and his comrades had to help him in everything he did. In the evening they all lay down to sleep in a snow-hut, but he did not know how to set about this either.

"How does one rest in a snow-hut?"

"One sleeps best if one pulls one leg out of the trousers," the others replied.

This he did and soon he was fast asleep.

But as soon as his comrades saw his bare behind, they rushed up and buried a spear in it. And Angutdligamaq, bellowing with pain, jumped up in the air, and thereby forced the point of the spear still further in and died. His comrades then returned home.

"What has become of Angutdligamiaq?" the mother asked, she who was called Anoritoq, "The Windswept One."

"He was killed," the others answered.

"When next you catch a pregnant bear, then give to me the embryo that it may be my child," the woman begged of them.

Then one day, when the hunters had caught a pregnant bear, they brought the embryo home to the woman, and she reared it with blubber from her lamp, and soon it was so big it could catch seals for her.

The bear was called Anoritoq's son.

In the winter, when the great darkness came, the bear could no longer see to catch the seals, and then it started stealing from other men's meat stores.

You must not steal," the foster-mother anxiously warned it; your cousins will stop you and the people will kill you."

The dogs were called the bear's cousins.

"Oh, I will run away before the wind," the bear said, "then the dogs cannot scent me."

Nevertheless, one day things went wrong. The dogs stopped the bear, and the people killed it.

For many days the woman waited anxiously, for although nobody had told her, she feared that this animal, of which she had now grown fond, had been killed.

One day when, as usual, she had warned it not to steal, she had blackened one of its sides with soot from her lamp.

In this way I shall at least know for certain if it should be killed," she said.

She now told the people in her camp to drive out and ask in other places whether anyone had killed a bear with soot on one side; and before long sledges returned and told her that a bear like this had been killed in one of the neighbouring camps.

The woman sorrowed greatly when she knew that her foster-son was dead. Weeping, she left her house and sat down on the headland outside the camp. As she looked across the endless ice which had previously been the bear's hunting-ground, she sang:

Days and nights elapsed, and the woman would take no nourishment. Sobbing, she sang her song until the tears stiffened on her cheeks as her body turned to stone.

One still sees her lifelike form on the headland by the camp. Her mouth is covered with a layer of hardened blubber, for they say that it brings luck to the bear-hunter if, before he goes out, he tries to feed the bear-mother with blubber. And in the quiet winter nights, when the northern light sends its ghostly rays across the heavens, one sees old hunters going towards the mountain under some plausible pretext. The next day fresh tracks in the snow show that the bear-mother has had visitors, and her face glistens with blubber.

Before dawn, just as we had got up to light the Primuses, we were surprised to hear the barking of dogs and strange voices outside. Two young men had returned from a successful hunt of musk-ox in Ellesmere Land, where they had slain forty animals. They provided us generously with fresh meat and tallow; we then parted, each going his own way.

From Anoritoq to Renslaer Harbour we had a beautiful but strenuous day's journey. From Cape Inglefield to Cape Ingersoll we travelled through strongly pressed-up ice. During this part of the autumn the whole of Kane Basin consists of huge drifting ice-floes; the current here sets very strongly towards land, and, whilst new ice is being formed, blocks of ice are pressed up where the drifting floes freeze together. These pressure-ridges are often so tall that one must hew a way through with axes. The heavily loaded sledges have to be slowly and carefully worked across, so that they shall not be crushed in a sudden fall from a height of several metres; often they stick in awkward and desperate positions, where several men's strength is required to free them again. This is hot and laborious work, which, however, generally leads to so many comic situations that the task is shouldered with good temper.

Near Cape Ingersoll we climbed on to an ice-foot about sixty metres broad which stretched before us as a beautiful and easy snow-free road. Above us towered the high red sandstone mountains, with an even gradient of snow-clad talus at the foot and steep precipices near the top. The red rays of the evening sun were refracted on to the snow and the mountains, and with this beautiful landscape before us we drove at a rapid trot to the camp by Renslaer Harbour which the Eskimo calls Aunartoq.

The inner bend of this bay gives an exceedingly friendly impression. The country hereabout consists of beautiful rounded hills of light granite, with moss and grass peeping out wherever the snow is blown away. Along the coast tall, elegant, and proud sandstone mountains stand on both sides of the bay, like a majestic porch leading to the little cove where the Eskimos have built a camp. The coast mountains, especially at sunset, are tinged with red, which contrasts beautifully with the greyish-white gneiss in the sheltered cove from which an even and uniform high plateau stretches like a large plain right up to the inland-ice.

We were all curious to know how far Majaq would be able to keep his promise. He had spoken about masses of meat, but the Eskimo's idea of masses is often quite relative. As soon as we had made camp and tethered the dogs, I went with Majaq up to the little headland where his depot was supposed to be. With justifiable pride he pointed out over the plain and said: "All the meat which lies here is now yours; may your dogs grow strong on my catch."

I saw at once that the man had not exaggerated; on the contrary, it would be difficult for us to use all he had offered. Here were seals and meat in abundance. While the tents of the expedition were pitched and snow-houses were being built, we pushed the huge stones away from the meat-pits to get at the seals. Thirty-five large, fat seals we took, and four delicious bearded seals.

This represented such a large addition to the meat we already had that we decided to rest for a day for the express purpose of allowing the dogs to eat as much meat as they could possibly get down. We spent this holiday, which abundance of meat allowed us to take, in studying the historical place whereto Majaq's meat-pits had led us.

Majaq is one of the best hunters of the tribe, and is to be counted among those who are not fain to leave the neighbourhood of Cape York, where the bear-hunts in Melville Bay tempt one to remain. But last year he had promised his wife and half-grown son that for once they should be given an opportunity of a good airing for their clothes. They had lived by Cape York for such a long time that they almost stank with fixity of abode; therefore they had decided on this great removal.

Anoritoq had at that time been uninhabited for fifty years. The last man to settle here was called Eiderduck." Originally he had lived further southward, where there were many people, and where one thus did not suffer from the emptiness and longing due to the lack of people between the camps. But a local hunter had tried to rob him of his very beautiful wife, and as the wife did not appear to have sufficient respect for the "Eiderduck's" rights, the latter at last decided to move further northward.

But on their way through the camps along the lands they fell upon illness and bad hunting. This happened in the time when evil fate might sweep down on men suddenly and unmercifully; and at that time it was the custom to leave behind, in some empty house which they casually came across, those who could not keep up with the other travellers. As a rule, those left behind were children. Windows and doors were covered with large stones, too heavy for the exhausted ones to move; thus they were left buried alive. This was not done with evil intent, it was in accordance with one of the traditions of the restless hunters. Weeping, and with loud lamentations, they tried to get away as quickly and as far as possible from the doomed, who in the course of a short time died of starvation and cold. In this way the "Eiderduck" left his children, one after the other. Only one child, the parents' favourite, accompanied them on a sledge, bundled in a skin. But as during the journey they became half-witted through illness, hunger, and exhaustion, the "Eiderduck" in the end asked his wife to throw the child from the sledge, so that it might have a quick and painless death in the cold. And this she did.

The following day they repented of their heartlessness, but too late; and in their regret over their own inhumanity they continued to travel further and further north. At Anoritoq they met many people who lived happily; but sorrow weighed on their minds and they could not bear the company of people, so they continued their journey northward until at last they settled by Aunartoq. Here they lived alone for many years, and never travelled to visit other people. Those few who visited them always spoke of their great hospitality, but never did they open their mouths to let out a superfluous word, never was a smile seen on their lips. Once when someone went to visit them they were both found to be dead. There was a sufficiency of meat in their stores, and the visitors concluded that they had starved themselves to death so that they might follow the child which they had killed.

Since the "Eiderduck's" time nobody had lived by Renslaer Harbour; the place was in evil repute. First now in 1916 Majaq had moved out here, but although the catch of spring and summer had been so abundant that all his meat-pits were flowing over, he nevertheless moved in the autumn down to Etah, so great was his longing for companionship. Majaq chose to struggle through the dark period far from his own meat stores, wherefore his countrymen said that he was mad; but the loneliness had weighed on him so heavily in the place where lay the bones of the "Eiderduck" that he preferred to live in poverty among fellow-creatures.

The camp Aunartoq, the place where spring comes early, consisted merely of three houses, and these were all very old. Among some ruins I found a piece of a sledge which seemed to have been made entirely from whale-rib. There was also a whale's head built into the wall. It was strange to see that even so far north, in places where the ice seldom quite disappears, the whale has played an important part, just as it has done in other parts of Smith Sound. Besides these things I found bones of walrus, bear, and musk-ox, and, of course, an abundance of gnawed seal bones. Many meat-pits of the usual form were built about the houses.

I was somewhat surprised to find no bones of reindeer; for this peaceful expanse between the ocean and the inland-ice has, at any rate during an earlier period, given the necessary conditions of life for many reindeer. The reason may, of course, he that this place was uninhabited at the time when the Eskimos hunted reindeer. Strange as it may seem, the reindeer has been looked upon by the present tribe as an unclean animal not to be eaten. It was only after 1864, when the immigrants from Baffin's Bay brought new customs to the country, that one learned to consider the reindeer as a meat giver; since then it has been hunted with such thoroughness that it is almost extinct. The hunting conditions of Renslaer Harbour are briefly as follows:

Every spring many seals and bearded seals are caught by the Itut method on the ice; one can engage in Utut-hunting here practically all through the summer, as the ice generally remains on the water in the bays. Not until the middle of August does the melted water above the ice become so deep as to make this method of hunting impossible. Of late years the ice has not broken along the land, although very broad fissures have appeared round the headlands. Occasionally, however, walrus will be found in these clefts. Many hares are to be found inland, and occasionally reindeer.

In the afternoon as soon as our work about the meat-pits was finished and the bearded seals and seals cut up into pieces of convenient size for the requirements of our journey, we had a party. We could not help rejoicing because of the great abundance which Majaq's meat depots had suddenly added to our possessions.

The feast began with the production of a cinema film, which was a great success for all the actors. It was played near Majaq's hut, and even some of the largest and best of our dogs were allowed to take part in the play. The action of the play was as simple as possible, as it merely pictured the arrival of a lot of visitors to Majaq, who, with smiles and large gestures of the hands, led them towards the piles of meat which we had just collected from his depots. Here we then partook of a brilliant feast.

Although the proceedings amused them, the Eskimos regarded the performance merely as a series of mad antics, and the actors did not seem to put great trust in Ajako, who, during his visit to Denmark in 1914, had seen similar things, and now told them that the pictures would at some time become alive. They listened to his explanations but paid only slight attention to such postulates, as they did not wish to accuse Ajako of a loose connection with the truth.

Wulff handled the camera, and he did it in such a way that their spirits were further raised by the shouts with which he stimulated the actors. Unfortunately, a year and a half was to elapse before the result could be shown.

After this mimic feast we started a real feast on rotten meat of bearded seal. The bearded seal is usually divided among the hunters, the most coveted parts being those from which the indispensable seal straps are taken. But Majaq had already cut out so many straps from his great catch that the last bearded seals he caught were cut up without separating the skin and blubber from the meat. The result of this mode of preservation is that the big flensing pieces which are put down during early spring in stone mounds, far down in the cold soil, get only the slightest touch of decay. No ray of sun must reach the flesh which, when the sparing warmth of summer has gone, looks like half-dried, smoked meat, and tastes excellently. One very seldom sees bearded seal served in this way, and our appetites were voracious. Our dogs also were given their share, and although they numbered 185, they had as much as one dared to stuff into them without danger of bursting their internal organs. After the meat coffee was served, succeeded by an exhibition on ski which furthered digestion of the solid meal by much laughter. Very few Eskimos have any practice in ski-ing down the hills, and as most of their efforts resulted in somersaults, we had plenty of opportunity for the exercise of our diaphragms.

That evening will never be forgotten. Soon the sun would be shining night and day, but as yet it still disappeared below the horizon for a few minutes, and created at its setting those wonderful ranges of illumination on the sandstone mountains and the white snow. These beautiful moments are over as soon as the more uniform light of the midnight sun shines night and day. The landscape was wonderful, not merely because the coast with the broad ice-foot and the beautiful coast mountains was in itself so charming, but also because the whole of Kane Basin, with its irregular plain of pack-ice, gave a wild and grand view to the north; and every night the mountains of Grinnell Land appeared in the fleeing sunlight as burning, phantastic castles on the western horizon.

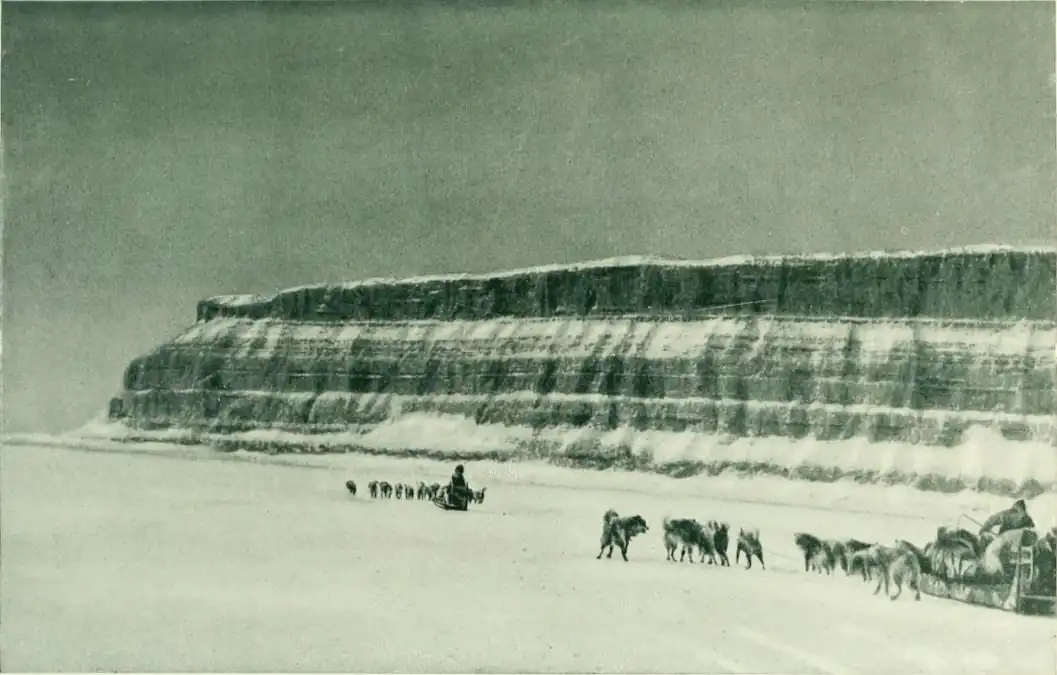

April 16th.—On the 16th of April we continued our journey northward on a broad ice-foot which gave easy and rapid progress. The ice-foot is only formed in places where the water ebbs and flows to a considerable height. When the water falls, at ebb-tide, the cold is already so severe by the end of September that the coast, up to the high-water mark, is covered with a crust of ice, a thin layer being deposited at every ebb. In the course of October and November the ice-foot has reached its full thickness and forms a belt along the coast, a ribbon of ice following all the branchings of the shore. The level of the top of the ice-foot marks the highest tide of the year. Viewed from the sea-ice it stands boldly like a wall.

Where the coast consists of steep mountains the ice-foot is quite narrow, because in these places it hangs on the sides of the cliffs without support beneath; but where the coast is flat the bottom of the sea supports it, and in this case it is often very broad. In no place is it broader than along the coast of Kane Basin, where it measures from sixty to one hundred metres.

It was a joy to us all to shoot along this lovely road. We followed the foot of the beautiful sandstone mountains which, with flaming red colours, fresh as ruddy cheeks against the white snow, flanked our way. Out to seaward of us were the pressed-up ice-floes of Kane Basin, where deep snow made bad travelling, and, as we passed above it, raised beyond all its difficulties on the chaussée of the tidal waters, wantonly we cracked our whips at all this devilment which we had robbed of all opportunity to trip us up and hinder our quick progress. Washington Land could already be discerned ahead. Everywhere was April's sun and high spirits.

At Cape Taney we passed four large tower-traps and six ordinary fox-traps; the former are rather common here but unknown in the rest of western Greenland.

A tower-trap is about 170 centimetres high, built in the form of a beacon; the Eskimos call it Uvdlisât, which signifies a trap which may be left for several days without inspection. The foxes are caught in the following manner: Rotten seals are put at the bottom of the hollow stone beacon, which is built in such a way that it is roomy at the base and very narrow towards the top. So as not to arouse the suspicions of the fox, the opening is covered with willow branches smeared with blood. When a fox jumps down into a trap it cannot get up again; and in the course of a few days several foxes may be caught in the same trap.

At Marshall Bay we divided into two parties, so that eleven sledges, with Dr. Wulff as leader, drove right out on the broad bay where travelling was easiest, while Koch and I with two other sledges drove inland by the head of the bay looking for Eskimo ruins. For our guide we had the great Tornge, who had lived here himself in 1916. His longing for reindeer-hunting had lured him to these northern parts. Next to bear-hunting, reindeer-hunting is the most exciting game an Eskimo knows. It is considered more "swell" to catch a bear, but otherwise the hunting of reindeer is without comparison the most elegant. Wild reindeer are very shy, and to get within shooting distance not only skill and cunning is required but also an incredible amount of endurance. They provide both tender and savoury meat and delicious tallow, and their skins are in great demand.

The place where Tornge wintered is called by the Eskimos Inugarfigssuaq or Great Blood-Bath Fjord." As in all places where human activity has left its marks, tales are bound up with the country. Tornge tells the following:

At the time when there were many people and all countries were inhabited, many houses were to be found by the Bight of Qaqaitsut near Advance Bay, not far from the great glacier.

One day two boys started fighting here; their grandfathers stood looking on. It so happened that one of the old men interfered and started thrashing one of the boys. But the other grandfather became so enraged by seeing his grandchild thrashed, that he went forth and killed the grandchild of the other man. But then the first grandfather killed the other grandchild and the murder of the two boys gave occasion for everybody at the camp to take sides; so the first thing they did was to kill both the grandfathers. This beginning made people wild and gave rise to a senseless slaughter. A madness which no one could explain had seized on the camp, and all travelled southward, fleeing and killing, so that all the little bays the sledges had to cross were filled with slaughtered men. And all the dead showed black against the white ice, just like seals sunning themselves on a spring day. How long the killing lasted no one knows; but suddenly they discovered that rage had carried them so far that really one had no quarrel at all with the man one killed. Then they stopped, heartbroken over the wrong they had committed. But the flight continued southwards to lands where the sun was warmer and the winter nights shorter.

And the largest of the fjords where most dead were lying was later on called "Great Blood-Bath Fjord. . . ."

This is a simple and naïve Eskimo tale of the origin of war—naïve, but eternally true wherever man kills.

This myth Tornge told us as an introduction to the tale of his wintering. He was interested in everything connected with the camp and the hunt, and with great perspicuity he gave us a picture of the life he had led so that all his great and small joys stood lifelike before us.

As a rule the winter-ice lies untouched until the following autumn. But the end of August or the beginning of September—so late that a thin ice is already being formed—the rivers melt round basin-like holes in the ice at their mouths, and a fissure which during summer-time has formed off Cape Russell widens out broadly. This is all the open sea they have.

The inland tracts were prolific in hare and reindeer. Tornge and three camp-fellows had killed no less than a hundred during the autumn. They had moved far into the country to some large lakes situated near the inland-ice, and here they had camped in small stone huts during August and September. These huts are primitive houses, having walls of stone and roofs of hide. Women and children accompanied the men on these expeditions, remaining by the huts while the men were hunting.

The best hunting memories of Tornge's life were linked up with his visit to the surroundings of Marshall Bay. The wintering had one drawback only—it was difficult to find sufficient food for the dogs, as the seals did not last out well. One felt the lack of narwhal and walrus, which yield more lasting food.

Eiderducks and ice-gulls were to be found in all openings of the ice, and on the lakes long-tailed ducks and loons.

During a hunt for reindeer, salmon was found on the top of Cape Russell at a height of about 300 metres. The lake was not very large, but notwithstanding this many salmon were caught, some of them as long as a man's arm.

In the camp were found altogether eighteen ruins of houses, with many tent-rings and meat-pits. Tornge's house was an old ruin which had been repaired. In the wall we found the remains of whale-ribs, and in the midden remains of whale, walrus, bearded seal, seal, musk-ox, reindeer, fox, and hare. Fishing-hooks made from the antlers of reindeer had also been found.

Tornge's house was large and beautifully built: it was of the type called Samisulik, containing a large main room with a small room at the side, both provided with benches. In the small side room his daughter and son-in-law had been living. A short distance away we found an unusually large ruin, which had an inside circumference of rather more than 30 metres. This points to the probability that local hunting conditions must have been, also during an earlier period, ideal. The headland where the houses were situated was full of gneiss, intersected by many well-grown grass meadows. The place looked kind and smiling; and there was plenty of water, both in rivulets and lakes.

Three kilometres from the mainland there is a small, steep, and rather inaccessible island of gneiss, whose entire breadth is about 200 metres, and whose length is 500 metres. On this little island we found no less than ten houses. This strange choice of a place of habitation was probably due to the easy access which it provided to the open sea by Cape Russell and Cape Taney; besides which, the ice outside the island is probably a better place for the Utut-hunt.

We named the island Avortungiaq's Island, after Tornge's daughter, who was the first to discover the ruins.

On another little island nearer land, ruins and houses are also found. The ruins, which are the remains of an earlier Eskimo camp, in this comparatively small bay number about sixty. In addition to the camps here mentioned ruins were found by Cape Russell, Cape Wood, Dallas Bay, and in the bight of Advance Bay. On the stretch from Anoritoq to Cape Agassiz one can thus reckon with at least a hundred houses—a surprising number. Good ice-hunting must have taken place here during spring and autumn, and, in connection with the land-hunting, which must have been uncommonly good for a district like this, it has evidently tempted many people to settle here. The country from the coast inward seems a perfect oasis in this desert, for one must go right down to the south before one finds such a broad expanse of land.

With the exception of the houses on the gneiss headland by Tornge's home, all ruins of houses on this coast are remarkably small in size. The ruins at Cape Wood consisted of eight houses in a row, built of sand. The bank of earth encircling the house was quite plain and large, and small stones had been added to it; but everything seems to indicate that the builders must have had some difficulty in procuring material. Remains of turf walls were not to be found at all, neither was there any trace of vegetation; the country was absolutely barren, and no peat was discovered in the neighbourhood. The camp gave one the impression of having been an "experiment station." The conditions for hunting must have been excellent. By a big stone near the houses one yet saw soot from a cooking-fire. Wherever possible the ruins were measured, but a proper exploration was out of the question, as we passed them in the beginning of April in 30° (Cent.) of cold. Everything was covered by deep snow.

April 18th.—On the 18th of April we reached Dallas Bay, from which, near by Cape Kent, we drove out on Peabody Bay to cross over to Washington Land.

The first day's journey we made fifty-six kilometres, though for the first twenty kilometres we had to toil slowly through deep snow. In some places we drove across awkward floes of old ice, similar in character to the edge of the inland-ice. These floes have a rugged surface with deep holes, due to many summers of sunburn; they look like a high sea, and the heavy sledges bob up and down on them as ships on the waves.

April 19th.—When we arrived approximately in the middle of the bay, we built a camp of snow-huts, and here for the first time we had an excellent view of Humboldt's Glacier, the largest glacier in Greenland, so highly praised by Dr. Kane. Our expectations were tremendous because of his picturesque descriptions, which really do give the picture of an imagination overwhelmed by the great unknown. I will therefore quote this white man, the first who set eyes on this region.

"I will not attempt to improve on reality by a flowery description. Man can only improvise about Niagara or the ocean. My notes speak artlessly of the long ever-gleaming line of mountains, and of the dazzling plain of ice. The mountain-line raised itself like a massive, glass-like wall, 300 feet above the sea, with unknown, unfathomable deeps at its foot; and its arched surface, sixty miles long from Cape Agassiz to Cape Forbes, lost itself in unknown spaces, no more than a single day's train journey from the North Pole. The inland regions with which it was connected, and from which it issued, was an unknown mer de glace, an ocean of ice of, so far as one can see, limitless dimensions.

"In my inmost mind I had expected to meet with such a great glacier if ever I was happy enough to reach the north coast of Greenland; but now, when it lay before me, I could hardly grasp it. Here it lay, plastic, movable, a half-solid mass, crushing out life, swallowing cliffs and islands, and forcing its way with an irresistible movement down through a frozen sea."

Reality proved a great disappointment to us. The glacier certainly was mighty in extent, for it was about a hundred kilometres broad; but for one who is accustomed to travel under the extravagant glaciers of Melville Bay, which in a single sneeze throw gleaming ice-mountains out into the ocean, Humboldt's Glacier seems to be merely a good-natured attempt at a half-dead ice-stream—scarcely capable of reproduction. The edge of the glacier, which, almost without crevasses, slopes evenly as a high road out into Peabody Bay, is in most places of a height not exceeding fifty metres. In several places it runs smoothly down into the water, so that it is easily accessible from a boat. Our survey showed that the water for the greater part in Kane Basin is very low; and the little ice-mountains, which approximately have the character of pieces of Sikûssaq, are aground. A measurement of their height proved that Peabody Bay, as far out to sea as fifty-six kilometres, was no deeper than forty metres.

Advance Bay itself consists of a lot of small, low islets, and the coast from Cape Agassiz is cut up by many shallow bights, so that a comparatively small rise in the ground here by Kane Basin would reveal large stretches of land. It is only possible to understand the nature of Humboldt's Glacier rightly by looking upon it as a continuation of the quiet and fissure-free edge of the inland-ice which runs down on Inglefield Land. Thus it is not correct to characterize Humboldt's Glacier as a glacier, but only as an even edge of ice to which the sea reaches up.

The overwhelming impression made on Kane and his followers by this glacier must have been due to its extent. I fully admit that, looked upon as an ice-stream, it is imposing in its calm and quiet enormity, even if its kindly round back is quite different to what one would expect from the largest glacier in Greenland.