Greenland by the Polar Sea/Chapter 4

MAY 2nd.—We started at ten o'clock. We expected bad driving, and we got it. According to its position, the Polaris Peninsula lies like a wedge in the midst of a strong drift of ice-floes which, under the pressure of all Lincoln Sea, break their way past the large capes to be ground in through the narrow Robeson Channel. By midnight we had nearly reached Cape Sumner and made camp utterly worn out. The dogs also were worn out by the pressure-ice, and as soon as the signal to stop was given they laid down almost on top of each other, never stirring all through the night from the spot where they had flopped.

The quality of the ice showed that there had been open water along the coast until late in the autumn. From Hall's Grave to Cape Lupton we therefore had excellent going, but here the character of the ice changed, and, as it was not always possible for us to follow the belt of the tidal water, we often met pressure-ridges which towered up in front of us to a height of 10 to 15 metres. It was quite impossible to drive across these huge blocks, which lay piled together as if thrown there by a giant's hand. For hours we had to stop in order to make a road for the sledges with our ice-picks.

In some places the ice was pressed up towards land, lying like an exquisite diadem round the ice-foot, gleaming in beautiful colours when the rays of the sun caught the many broken crystals.

While the country south-east of Hall's Grave is low with occasional rounded hills, the north coast stands like a steep wall of cliffs with a beautiful design in brown and grey on its enormous flanks. A snow-shower had just swept the awl-pointed peaks standing in white and brilliant contrast to the dark bands lower down.

There was a storm from south-east, and the gusts of wind swept down from the mountains with such force that it was impossible to stand upright under their attacks. We pitched the tents with great difficulty, and as soon as we had strengthened ourselves with some food, little Hendrik and I walked along the ice-foot to Newman Bay to reconnoitre. We crawled up on the ice-foot and crept slowly forward against the storm. What we saw was not very encouraging; on the morrow we should once more have to hew our way towards the bay where the ice seemed more even. We climbed the mountains to get a view of the places where travelling might be easiest; then we returned to our comrades. On one crossing of the mountain we were overwhelmed by weariness and the pain of our wind-lashed faces, so we sought shelter behind a hummock of ice.

Whilst we tried in vain to doze, our thoughts reverted again and again to Markham's journey across this very Polar-ice, through the frozen spray of which we were now about to force our way.

I have mentioned before in how slight a degree we were impressed by the natural phenomena which so often had rendered our predecessors speechless. But here, where for the first time in my life I looked across the mighty ocean of the Pole, I had no words to express the feeling with which this living though ice-bound sea overwhelmed me. The infinitely distant horizon, where on all sides one sees only endless white ice-steppes, lying there without the evenness of the plain and full of unrest, is like an Epos of nature which renders one dumb.

And whilst the wind raged round us and the steep mountains of Cape Sumner stood threatening above our heads, the surroundings forced me to go through again in imagination all the sufferings which the stubborn Englishmen from Nares' Expedition had undergone.

Right opposite to me was the north-east coast of Grant Land and, as a blue line in the horizon, the faint contours of Floeberg Beach, the Alert's winter harbour.

Nares' Expedition of 1875-76 was made at the expense of the British State during the reign of Queen Victoria, and was equipped with everything which at that time was considered necessary for Polar exploration. Expense had on no point been considered.

The expedition left Portsmouth on the 29th of May and arrived at Disko with three imposing ships; from this harbour one of the ships, the Valorous, was returned, so that Nares had now command of two big, strong ships, the Alert and the Discovery. The plan was that one of the ships should go no further than N. Lat. 82°, where it was to take up its winter quarters. The other ship was to push on as far north as possible.

The goal of the expedition was the North Pole, and, as soon as it had passed Cape York, it worked its way systematically northward, leaving in all suitable places depots to be used in case of shipwreck. Simultaneously beacons were built where information was laid down for eventual search expeditions. It was one of these depots which we found at Cape Morton, as previously described.

According to plan, the Discovery took up its winter quarters in Lady Franklin Bay, whilst the Alert made its way up to the north point of Grant Land, which it reached on the 25th of August. The winter was spent on Floeberg Beach.

In the beginning of April, 1876, all the long sledge journeys started, which, due east, seaward due north, and due west, were to accomplish the task of the expedition. I will mention here only Markham's voyage.

Markham's task was to push northward as far as possible, preferably to the North Pole itself. He started with a train of nineteen men with sledges whereon provisions and baggage were distributed in such a way that each man would have a load of 230 pounds. Besides the sledges they also brought two boats much too heavy and unwieldy for such a long sledge journey. Very soon after the expedition left land, they had to leave the first boat behind.

Daily these men fought a terrible fight against both the cold and the natural obstacles in their path, and it was not long before they began to suffer from frost-bite. They faced this misfortune bravely. But when the dreaded scurvy[1] made its appearance, the expedition was on the point of breaking down altogether. On the 19th of April it became evident that three of the men had contracted this dreaded and terrible complaint. On the 24th, N. Lat. 83° was passed, and then no less than five men were ill and unable to do any work. On the 7th of May the position was already such that three men had to ride with the baggage, while two of the patients were yet able to manage for themselves, although they were hardly able to walk. On the 10th of May it was obvious to Markham that it was hopeless to continue, and, while the patients were given two days' rest, he himself and the strongest of the men set out on an excursion to N. Lat. 83° 26', the farthest north ever reached—a record which was destined to remain unbeaten for many years.

On the commencement of the return journey five men had to drive, whilst a further five were only enabled to keep up with their comrades because the drivers must cover the distance three times in succession to bring up all the baggage. When they approached land, still another three men fell ill, and as there were now only two officers and two men left, they decided at length to leave the second boat, which they had dragged along fearing that they might meet open water.

On the 5th of June they reached land, and after two days of rest Lieutenant Parr had sufficient strength to cover the distance to the ship on foot. A relief party was promptly sent out, and all the men were brought on board, but several of them were already so ill that, in spite of all efforts, they died after having reached harbour. The men who left the ship were fine fellows—they had been picked from a large crew; but of what avail is youth and strength when the constitution is undermined by scurvy?

This is briefly the tale of the first journey across the Polar-ice, which now lies before us. The story the ice axes hewed out here was just as gloomy as, in consequence of its surroundings, it must necessarily be. It was a fine and noble record, and Markham has for all eternity carved his name on the scroll of the foremost in Polar exploration; but hard was the journey and dearly were the results paid for, for this great cold Polar Sea claims a sacrifice from every man who tries to unveil its secrets.

Hendrik and I got up stiff with cold, but were blown homeward and soon got warm. Often we were flung along the ice against pressure-ridges which did not receive us kindly; and it was with genuine joy that we arrived, bruised and stiff, at the camp of our sleeping comrades at four o'clock in the morning.

This was a cold and inhospitable coast!

May 3rd.—We had pitched our tents between the big pressure-ridges close to the ice-foot, attempting to find shelter from the storm.

The landscape would have been gloomy had it not been for the warm sun, which gave life and colour to everything: even the precipitous mountains behind us changed in warm tinges.

We hoped that we should wake up in quieter weather, as the gusts of wind made progress so difficult on the shiny ice between the big ridges. During a storm one is unmercifully flung down, and the dogs, which had worn down their claws during the last days of fighting for a foothold on the shiny ice, were swept together in bunches which were flung against the sledges; here they lay until a lull in the heavy squalls gave them a chance to push ahead for another short distance.

We had the same weather to-day as yesterday, and we pressed on to get out of this awkward neighbourhood; in the course of the day we reached the strongly folded ground of Cape Sumner, from which point driving was easier, resting us whilst we passed Newman Bay.

I discovered no young ice in the bay; everywhere was several years old Polar-ice, hilly and rough, slippery and bare of snow, but nevertheless fairly easy to cross, as it was not necessary for us to use our axes. In the afternoon we camped near Cape Brevoort, a high limestone mountain standing as a counterpart to Cape Sumner.

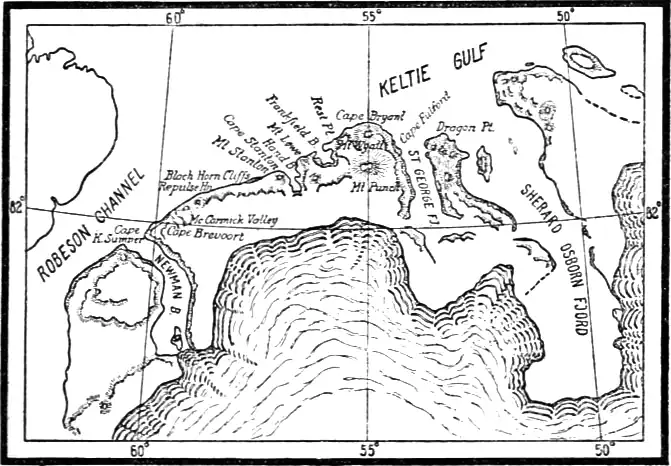

These monumental coast mountains are worthy memorials of the two American senators whom Hall wished to honour by this christening. From their summits one has a view not merely over the Polar Sea and the north coast of Grant Land, but also far inland across the country behind Newman Bay, where the land at an even gradient trends inward, ending in a great tableland near the inland-ice.

The success with which Hall's people met on their various hunting expeditions in this neighbourhood tempted us to try our fortune once more. The musk-oxen had had a close season of many years' duration, ever since the days of 1871, so two men were now sent out. Ajako and Bosun walked for ten hours across the stony land, and then returned tired and footsore to the tent, late in the evening, without having seen any sign of game.

May 4th.—One day succeeds the other in great monotony during this period; all our attempts to find game for ourselves and the dogs are unsuccessful, but we have yet sufficient stores to continue the journey on full rations.

The fight for progress through the Polar pack-ice was monotonous and strenuous. Hour after hour was spent in the same way. Sometimes the axe had to break the ice-blocks; sometimes we had to lift the sledges when they toppled over; and the whole time we had to force the dogs forward with iron-fisted discipline, through sharp and slippery blocks of ice where it was difficult to find so good a foothold that the sledges could be pressed through the difficult passages without delays.

At all the great capes the same pressure-ice was piled across the ice-foot as an obstructing wall, through which we could not hope to pass. We therefore had to work our way either along the belt of tidal water on the shiny ice, or, where this was impossible, along those rare places where a belated lane from January and February had stretched an arm of young ice towards land. But we tried as far as possible not to get too far out to sea, as these new lanes often end in a culde-sac and force one into a wilderness of pressure-ice.

During the forenoon we passed Gap Valley, where Beaumont and his men pulled their heavy sledges up across land when they found the route forward blocked by open water near Cape Brevoort. As the name implies, the valley here forms a broad gap between two steep mountains, a stony valley full of cloughs which goes in towards the great lowland near Newman Bay. We who have our dogs to help us bow down in deep respect to those sick and exhausted men who themselves had to pull their heavy, iron-mounted sledges up across the trackless terrain with its many large stones which lay bare of snow. Maybe those old pioneers were unpractical as regards their equipment, but what stubbornness and pride they must have possessed, these enduring and herculean mariners who were the first beasts of burden for the Polar travellers!

Near Repulse Harbour we succeeded in climbing on to an ice-foot along which driving was possible, although the gigantic Sikûssaq ridges in some places towered up and formed banks from 10 to 30 metres high. These phenomena testify to the fights which every year are fought out between the creaking, current-harassed ice-ocean and the mountain-sides, the outposts of the lands. Inukitsoq, who during one of Peary's Polar Expeditions wintered on the north coast of Grant Land, remembers that he has seen rifts and holes with open water far into the winter. It appears that the ice here between Greenland and Grant Land is seldom firm and dependable until February or March.

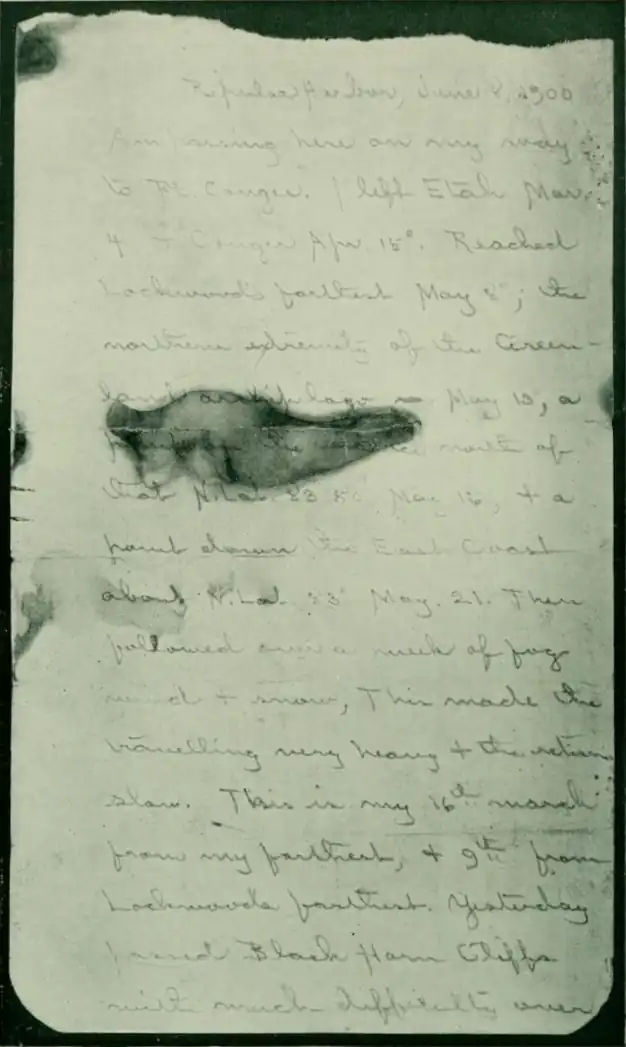

Near Repulse Harbour we passed a beacon as tall as a man, where, in an empty brandy-bottle, we found the following record from Peary:

"June 8th, 1900.

"Am passing here on my way to Ft. Conger. I left Etah March 4th and Conger April 15th. Reached Lockwood's farthest May 8th; the northern extremity of the Greenland archipelago on May 13th; a point on the sea-ice north of that N. Lat. 83° 50' May 16th; and a point down the east coast about North Lat. 83° May 21st. There followed over a week of fog, wind and snow, this made the travelling very heavy and the return slow. This is my 16th march from my farthest and 9th from Lockwood's farthest. Yesterday passed Black Horn Cliffs with much difficulty over loose ice. There is open water now off this point and a lane of open water this side of C. Brevoort extending clear across the channel. Have with me my man Matthew Henson, one Eskimo, 16 dogs and 2 sledges, all in fair condition.

"This sledge journey is part of a program of Arctic work undertaken by me under the auspices of and with funds furnished by the Peary Aretic Club of New York City.

"R. E. Peary,

"U.S.N."

We were now free of the pressure-ice and enjoyed the even going inside the fjord-ice. But unfortunately the sledges ran heavily on the snow, which, here mixed up with little grains of sand and gravel, hampered our iron runners. It was with great difficulty that we made the dogs keep up a slow trot, but this, nevertheless, represented a good push forward. On this stretch of the coast Wulff found a living saxifrage with fully-developed flowers on stems an inch high; in full bloom it had been suddenly surprised by the winter, which it had allowed to pass over its head as if it did not exist at all, and it quite calmly continued its life now when spring and sunshine once more melted the ice. All its tissues were full of life although the temperature of the air was minus 11° (Cent.), and there had as yet been no thaw during the year.

Near Black Horn Cliffs we made our camp after twelve hours of driving, as neither the dogs nor we ourselves could stand any more. After a slight meal and a refreshing cup of tea I climbed the mountains with the Eskimos so as to ascertain what conditions for travelling the next day would offer. The ice was similar to that of the preceding days, and in spite of all difficulties this was a pleasant surprise; for the ice of Black Horn Cliffs, which run steeply into the sea without a trace of ice-foot, is not dependable, open water being often found.

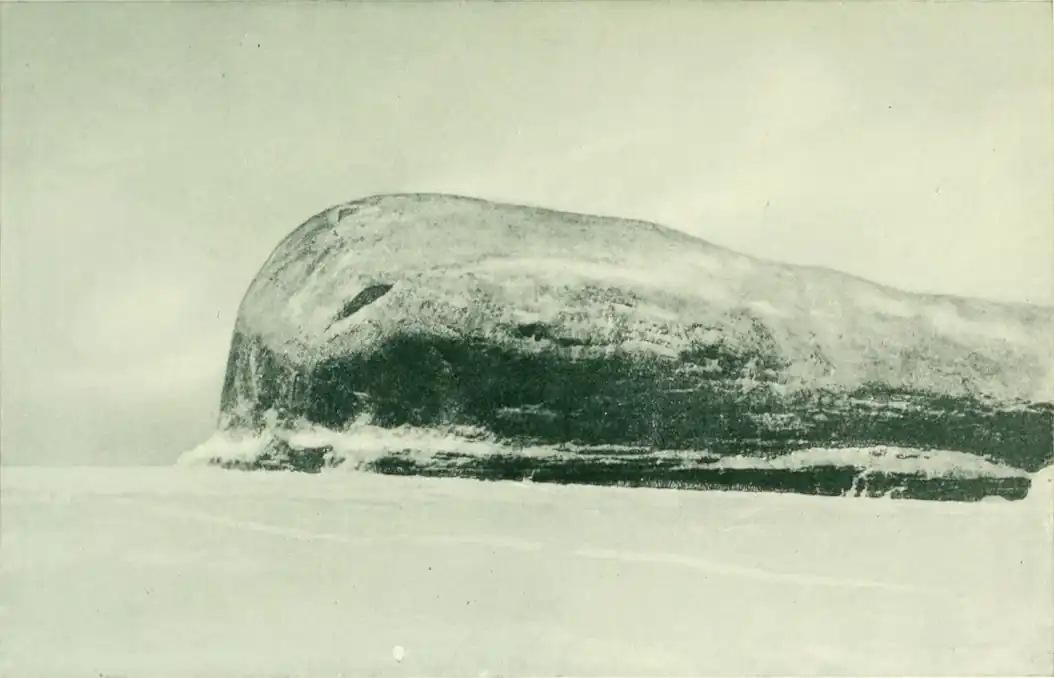

Inland we looked across even land with knolls which almost entirely consist of pebbles, clay, and sand. In spite of the absence of vegetation, the view, with its soft, calm lines, is a kindly one. Behind it all the mighty Mount Punch was enthroned, broad and solid with a skull-cap of white snow.

The land was bare of snow and in vain our two good field=glasses ransacked plains, valleys, and cloughs. Not a hare, let alone a musk-ox, was to be discovered anywhere.

From the wind-swept look-out of our mountain we could see clear across to the country round Grant Land, looming far, far to the north amidst a sea of ice like blue banks of fog. Furthest away Inukitsoq recognized Cape Sheridan, the winter harbour of Nares in 1875-76, and later on Peary's quarters during no less than two Polar expeditions.

Looking from this point across the huge plain of rugged Polar pack-ice with very occasional narrow lanes of new ice, one cannot but feel the greatest admiration for the old English sailor who already forty years ago found a way for ships so near to the North Pole.

May 5th.—As usual, we camped on the ice between the highest ice-banks so as to be sheltered from the sweeping blast which whirled across the ice-foot and whipped our tents with showers of snow and gravel. An inhospitable country to wake up in when the day's journey must begin after a good night of rest in a comfortable sleeping-bag! Each day has to be started with a little reconnoitring. One or two men go seaward armed with ice-picks in order to rid the road of the first obstacles. It is always a good thing to get quickly away from a camp, for nothing is more demoralizing than looking too long at the place where last one slept.

We soon found that by going seaward we quickly came across fairly good ice, though it was old Sikûssaq with slippery hilly slopes and annoying hollows. But this old ice alternated with good driving, and thus it happened to our great surprise that we quickly crossed the place where we had expected the greatest struggle. Near Cape Stanton we once more got up on the ice-foot, which was everywhere bounded on its outer side by ridges of from 5 to 20 metres high. We were now rid of the pressure-ice, but the clayey snow gave the dogs hard work in pulling the sledges.

During the previous day's journey we had seen tracks of Polar wolves, a very large male and its mate, which a few days ago had travelled in the very direction in which we were now struggling. On this day also we ran across the same tracks, and the dogs, which scented the strange animals, were animated a little by the hope of a possible hunt. Also we were interested in the tracks, for where wolves exist one will, as a rule, find musk-ox, and we were all longing for fresh meat. In several places on land we found excrements of musk-ox, but unfortunately they were all very old and covered with moss.

So far the day's journey differed only from the many others of laborious and weary struggles along a monotonous and barren coast, in that we passed two beautiful bays. There was Hands Bay, with two peaceful valleys edged by high mountains which further emphasize the idyllic aspect; at the head of this bay the ice was even and appeared to have been melted during the summer. Similarly in Frankfield Bay, which with a narrow mouth cuts broadly into the country. The background of this country is formed by Mount Punch with its genially-sounding name, lifting its snowy cap rakishly towards the clouds.

The wind appears to be the only guest in these harsh tracts where even the snow is forbidden to lie as a cover for the sparse vegetation—the charitable gift of summer to the insects, the little birds, and the stray hares and lemmings. But there was sufficient food for musk-ox, for wherever small, clough-like hollows give shelter for the snow, or where a river forces its way from some lake towards the ocean, there is plenty of grass and willow.

The result of the hunt was three lean ptarmigans. One of these was so tame that Harrigan, stealthily creeping towards it, got so near that he could easily take it with his hands. The ptarmigans were boiled in our porridge and imparted to it, with their keen delicious juices, a new and agreeable flavour.

Our two tents were pitched under a steep ice-bank, screwed up under the pressure of the Arctic Ocean to a height of 30 metres above the ice-foot. This bank looked phantastic with its many knotted ice-blocks crawling over each other, and provided a welcome screen from the wind. The place is called, quite appropriately, "Rest Point." The day's journey had been fifteen hours long, and, after this last wandering across the mountains, we all accepted the blissful rest which bathes our tired limbs as a rain-shower a thirsty field.

May 6th-7th.—It was six o'clock in the afternoon before we were once more ready to start.

Again on this day the ice-foot made travelling heavy. It was almost impossible for the sledges to get along because of all the sand and gravel blown on to the snow, and it was difficult to make the dogs go ahead. The coast was desolate and cheerless, monotonous and depressing. The ice-foot on which we travelled is along its inner edge covered by rather low rounded heaps of gravel, without character and entirely without the variation of form which otherwise breaks the monotony. Everything about us bears the stamp of the iron climate of the country. The eternal blast has whipped the sparse vegetation flat along the ground, nothing has had a chance to grow erect. All life here bears the yoke of storm and frost.

We snailed along from headland to headland, and every point of land ahead looked like the one we had just passed. The whole coast is clipped and cropped, blockaded by ice-ridges and chilled through by an ocean of ice.

We made occasional halts to give the dogs a short rest, and, in the meantime, we ourselves walked into the sandy desert, where not the slightest track encouraged us to persist. The crushing monotony of death seems to be the only ruler in this district.

During the journey I suddenly discovered a piece of wood placed by human hands in a conspicuous place near a large stone mound. Although in a way it formed a link with other men who have visited this coast, owing to our mood our thoughts involuntarily turned to graves. I hurried up to it to see whether it was not some sad memorial or other connected with Beaumont, but soon discovered that this place had once been merely a depot of provisions, perhaps a salvation for those who, starving and exhausted, managed to reach it.

The coast trends sharply and straightly due north-east and permits no view ahead; little headlands continually block the horizon. But under Cape Bryan the coast suddenly turns southward and opens at once the view to the north, where all the lands which we had dreamed about for months rise up from the ice-ocean and show their brilliant contours in the clear, sharp air.

It was two o'clock in the morning. The sun had not yet reached such a height as to emit a flat and monotonous light; sharp shadows were thrown on to the dark mountain walls, and a fine, tender red still trembled round the topmost peaks, covered in ice and snow.

It suddenly seemed as if the low, dreary coast which we had followed from Rest Point sank into the ocean behind us and no longer existed. We could now see far ahead, and with the wide view came that excitement of travel which always carries one across dead points; it was as if suddenly we approached our fate with visors raised, in a manner much more dauntless than before.

Quite near us we saw St. George Fjord, narrow as a river of ice cutting into the land, encircled by high mountains, which, with steep fells seaward, run right in to the inland-ice.

Dragon Point juts out like a wedge between this narrow fjord and the broad, far more impressive Sherard Osborne Fjord, where the broad lines, with the quiet country behind Cape May, put one in a mood quite different to the one created by the wild St. George Fjord. There is a breadth here and a depth, a wild monumental grandeur which fascinates one, especially when one looks upon it from this point and contrasts it with the rest of the landscape. Far seaward one gets a glimpse of Beaumont Island's sharp profile, like a clenched fist in the midst of eternal snow. Even the highest mountains here do not seem to be covered with snow, thus forming an agreeable contrast to the white immensity spreading out at their feet. Across the lowland behind Cape May, where the cone-shaped Cape Hooker dominates the horizon, we discern Cape Britannia's gimlet-pointed peaks on John Murray Island near the mouth of Nordenskjöld Fjord.

The sky was dazzlingly clear, the air deep blue and fresh, and it was as if the wind itself had other songs here than on the dead coasts from which we had come. On the uttermost horizon of the ice-ocean one sees occasional mirages lifting the sun-bathed pack-ice up towards heaven, giving relief to the monotony which rests over the frost-bound ocean. The immensity, the power and violence which Nature breathes here, where we have halted for a moment so as to take possession of all these new things, communicates itself to our will; and with the enthusiasm only known by men who have dared to leave the high road for the by-ways, we approach the land which holds our future fate.

The glorious immensity gives us new power, and merrily we turn the dogs down across the ice-foot, driving to Dragon Point along the even ice of St. George Fjord.

At five o'clock in the morning we land on the outmost point, and for the first time for a long period we stand where the rays of the sun are allowed to warm us right through. Not a wind stirs, and a tiny, curious bunting circling above our heads gives us a welcome to our first spring camp.

- ↑ J. Lindhardt, M.D., Professor at the University of Copenhagen, and member of the Danish Expedition of 1906-08, has kindly supplied me with the following information: "Scurvy (scorbut) is an illness due to an improper dietary, the cause of which is now attributed to the lack of vitamines in the food. These vitamines are to be found in fresh meat, and, more especially, in vegetables, but they are destroyed by unsuitable preservation. Thus they are not to be found in the salt meat which previously constituted the chief food of Arctic expeditions. The illness manifests itself by tiredness and weakness, often accompanied by pains similar to rheumatism, hæmorrhage under the skin, sores on the legs, often also on internal organs, and a peculiar affection of the mouth with swollen, tender, and delicate gums which give rise to hæmorrhage and wounds and, occasionally, a loosening of the teeth. The treatment of the illness is hygienic-dietetic (fresh vegetables). In severe cases death follows general exhaustion or is caused by complications, especially affections of the lungs."