Greenland by the Polar Sea/Chapter 5

IN the month of May, forty-two years ago, in the very neighbourhood through which we are now travelling, one could have seen a remarkable trail of sick people, exhausted and stumbling, fighting their way through the snow for the purpose of mapping the land, and later on in order to save life and results under an immensely toilsome wandering southward. It was Beaumont and his men from Nares' Expedition.

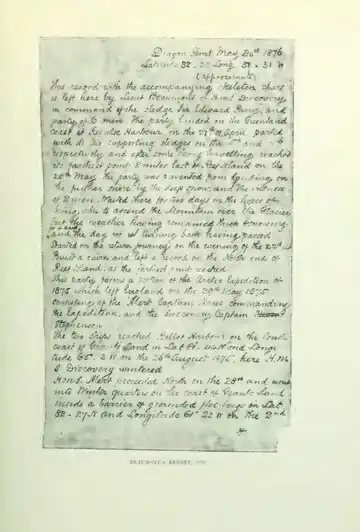

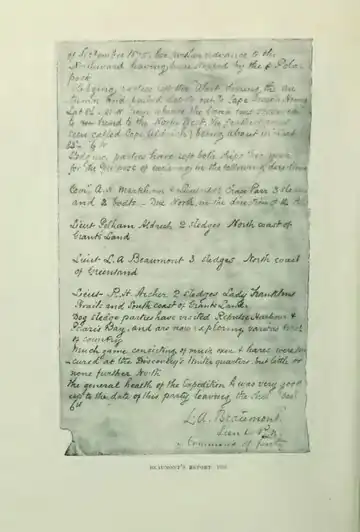

On our expedition we had passed many historical points, but here more than anywhere else did we feel the contact with those brave Englishmen whose goal was identical with ours, and whose trail we had hitherto followed. As soon as we arrived we discovered in the mountain a beacon, which we visited, and here we found Beaumont's report of the 25th of May, 1876, deposited in a beautiful, water-tight copper case. Besides the report, of which I here give a facsimile, we also found an original map of the tracts which had been visited and charted with English thoroughness. We took this record so that it might later on come into the hands of the British Admiralty as a chapter of Polar history, and put down another record in the same beacon, seizing the opportunity to express our admiration for our brave predecessors.

Lieutenant Beaumont set out from the Alert on the 20th of April with a band of twenty-one men, pulling four sledges on which the loads were so distributed that every man would be pulling 218 pounds—a rather stiff proposition.

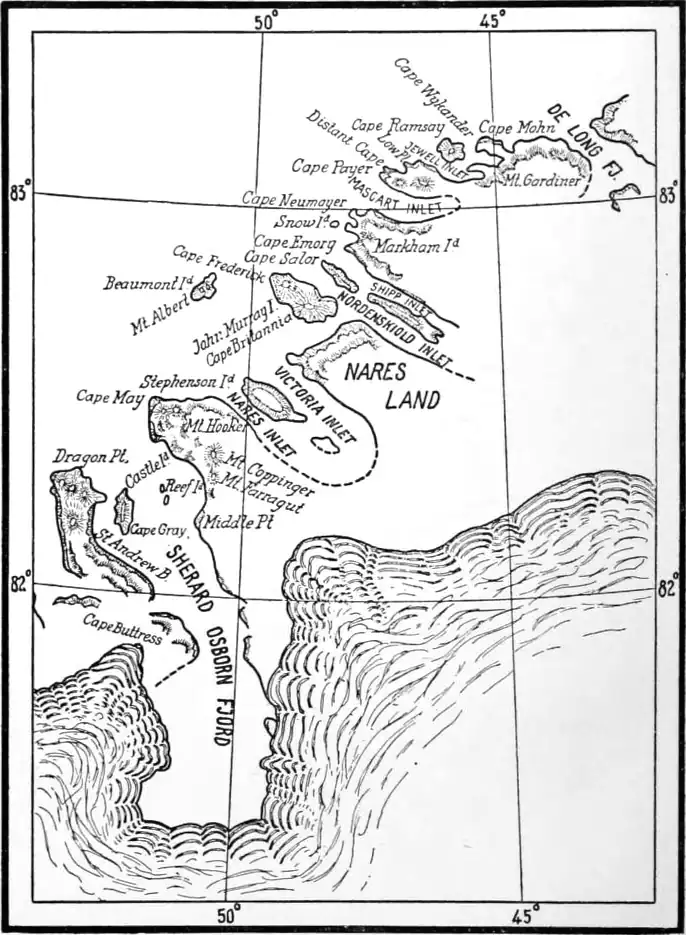

In the course of a week they reached Repulse Harbour and built the beacon, which we passed on the 4th of May, where Peary's record was found. In the same place a rather considerable depot was laid down for the return journey, and they continued their push forward on the 27th of April, no longer on the ocean-ice, but along the ice-foot just as we ourselves had done. Black Horn Cliffs were passed, and immediately afterwards a new store was deposited for the return journeys. Dr. Coppinger then left the party, as after the deposition of the stores the assistance of him and his men was no longer required. On the 10th of May the discovery was made that one of the men had contracted scurvy, and Lieutenant Rawson was immediately sent back with the sick man in an attempt to reach the ship. The others continued to put down depots to secure their retreat; thus one was deposited by Cape Bryan, which is no more than one day's journey from the previous depot. From this point they went via Cape Fulford across to Dragon Point, where we ourselves at present are camping.

As the illness spread among the men it soon became obvious to Beaumont that he could not succeed in reaching very much further north. He now wished merely to climb a high mountain on the north coast of Sherard Osborne Fjord so as to take bearings in the direction of the land which must be found, but which so far had remained hidden. For this purpose he chose a large cone-formed mountain, Mount Hooker, and he now bent all his energy towards reaching it. But the snow lay deep everywhere, and when the people could no longer bear up, Beaumont set off alone to see what sort of travelling he would meet with further on. Of this he himself writes the following:

"The coast which we tried to reach did not appear to be more than two miles away from us, and I therefore went on to examine whether it would not be easier to travel by land. I covered about one and a half miles in three hours, and then gave it up.

"My strength was nearly exhausted, and I hailed the men and told them to have their lunch, but I myself would rather forego three meals than walk all the way back."

On the 19th of May Beaumont writes:

"No one will ever be able to understand what hard work we had during these days, but the following may give them some idea of it: When we halted for lunch, two of the men crept on all fours for 200 yards, rather than walk through this terrible snow."

On the 22nd of May they were forced to begin the return journey without having reached Mount Hooker. Subsequently a report was left on the small Reef Island, and also the one on Dragon Point which we had now found. We decided to take only the record from Dragon Point, as the other one, which would probably be similar to ours, ought to stand as a memorial of English endurance here in the very country where the work was done. During the last days of May everybody with the exception of Beaumont and Gray was ill; they therefore had to leave behind various things which were not considered absolutely necessary, as the point was reached when the exhausted men had to ride. The first who fell was a sailor named Paul, and another followed him on the 7th of June. On the 10th of June they reached the depot at Repulse Harbour. They had plenty of provisions, but unfortunately it was just the provisions which had caused the disaster.

Open water prevented them from crossing over to the Alert, so they decided to travel down to Hall's Grave. The day after they had altered their course a seaman named Dobing died, and another man named Jones had, because of his weakness, such an awkward fall that he had not the strength to go very much further. How they managed to pull the sledges up Gap Valley, with all this illness and exhaustion, is a perfect riddle to us who have looked at the stony pass. The English will, which often stiffens into obstinacy, manifested itself here; there is nothing to say but this, that as there was no other way they went up through Valley Pass. We others can only bare our heads to those who did it. At last they reached Newman Bay, where Beaumont himself, as it was no longer possible to pull all the six comrades along on the sledge, intended to go to Hall's Grave, for there was a possibility that a relief party might have been sent out and would be waiting there. And there fortune met them, and saved those who could still be saved, as they fell in with Lieutenant Rawson, Dr. Coppinger, and Hans Hendrik with his dog sledge.

After a long rest near Hall's Grave, Beaumont continued his journey across Hall Basin to Lady Franklin Bay, where the Discovery was lying. On the 14th of August, after a most adventurous journey on drifting ice-floes, they at length reached the ship.

We now started in earnest. Our expedition had covered the first thousand kilometres of the journey, and we were already in tracts where we might hope for a good hunting. We had left home with provisions for two months, but half of them we used up on our journey, the other half being deposited a short distance below Beaumont's beacon. This latter half consisted of pemmican, biscuits, coffee, oats, tea, sugar, tobacco, and a quantity of ammunition, the last so far superfluous. We hoped that, before our departure, we should be able to supplement this with some fresh meat for ourselves and the dogs. We did not yet know from which point we should ascend on to the inland-ice on our return journey, but as the probability was that it would take place here, we relieved the sledges as soon as possible of superfluous things, so that we should not drag on unnecessary baggage. We also left two sledges, and the teams of these were distributed among the other sledges. Above everything, it was of importance that we should make good speed, and so we burnt our boats behind us by providing ourselves with food for men for three days only, and for the dogs only one meal, which would be given to them the first time we made camp.

We had now six dog teams of altogether seventy dogs, and if these could only have a few days' rest and strong food, they would soon regain their full strength. At the moment the position, so far as the dogs were concerned, was somewhat critical; the fight against the pressure-ice had obviously worn down both their bodies and their tempers. They no longer walked proudly with tails erect, the expression of their eyes was subdued, and their skins no more possessed that glossiness which is the surest proof of well-being and strength. Their tails flopped limply between their legs, and we all felt it our duty to restore their strength as soon as possible.

A reconnoitring in the neighbourhood had a discouraging result. We walked far into a snowless, stony terrain, but nowhere could we find fresh tracks of musk-ox. Scattered flocks seemed to have been here many years ago, but not even the clay showed recent tracks. Of ground game there was a fair amount of hares; they were very shy—an unfailing indication of the absence of musk-ox. In all places where the hares eat grass side by side with the wandering wolves, they flee as soon as they get a glimpse of any other living thing. And, according to the tracks, it would seem that there were not a few wolves. It was obvious that the hares were used to meeting enemies only. But where they live on land with peaceful muskoxen, they show, on the contrary, no nervousness even if one takes them by surprise rather suddenly on the hill-crest.

We often saw ptarmigans, but only in single pairs; but these were too small, so for the time being we would not kill any great amount of them. Their white winter coats, which previously made them so conspicuous in snow-bare spots where they seek their food, were already beginning to give place to the brown feathers of the summer. They filled the landscape with their cooing, which between these silent mountains sounds like a song in the loneliness.

The tableland inside St. George Fjord, dotted with mountains, so far did not tempt us to waste our time hunting; and those parts of Sherard Osborne Fjord which from the mountain we had been able to survey with our field-glasses were, to our great disappointment, so glaciated that a visit there would be too risky. I therefore decided to postpone the exploration of these fjords for the time being, until we felt our existence somewhat secure by successful hunting. We were beginning to feel a little of the hazard which is bound up with the life of the Eskimo and of the expeditions, whose future, after the manner of the hunters, depends upon hunting on new grounds.

May 8th.—We have been continually looking out for the snow which caused Beaumont and his men such great difficulties, and only to-day on our way to Cape May do we find it. For the first time since we left Thule the dogs lie down and refuse to continue, and, so that the whip might not be used too industriously, we prefer to go in front on skis. The dogs then willingly follow, dragging the heavy sledges. We have all taken to our snowshoes and skis, for without them it is quite impossible to make one's way through the snow. Once more we admire Beaumont and his men who, with the intolerable pains of scurvy, stumbled across ground like this, with stiff legs, tender, skinned feet, and, from the traces of the sledge, sores on shoulders and back.

After six hours of toilsome marching, we reach a large block of ice where we make a halt, as thick weather from the west draws across the fjord and blocks our view. A clammy fog envelops everything and a raw breeze gives us a gloomy greeting from the Arctic Ocean.

May 9th-11th.—The following day we have to continue in the same weather, for it would be impossible to remain here. Some distance from Cape May the weather clears and turns out fine, and we hurry ahead and reach land after six hours.

We round Cape May through difficult pressure-ice, and when we have passed a headland where the ice is even and bare of snow, the dogs set off at a trot whilst we ourselves for the first time during a long period throw ourselves down on the empty sledges.

We know from previous American expeditions that half a score of years ago there were musk-oxen in this neighbourhood, and I therefore decide to try to hunt in earnest before the dogs are too far gone. Ajako and Inukitsoq are sent up through the valleys to some large mountainous stretches, topped by glaciers, which certainly appear more generously covered with ice than suits us. Koch and I accompany them for some distance, and discover to our joy that the land here has a far richer vegetation than the barren coast between Newman Bay and Sherard Osborne Fjord. We also find tracks in the clay of musk-ox and a quantity of excrements which cannot be very old. And while the two hunters continue their way, each dragging his dog along, we hurry back to the sledges to find a convenient place for a camp further ahead.

As soon as we find a place, I run off to the mountains with Bosun and Hendrik, while Wulff and Koch are left behind to pitch the tent.

After a laborious climb up the mountain-sides, consisting only of small stones which slide downward under our feet, we reach the top of a high tableland stretching inland. We pass two skeletons of musk-oxen, but they are too old to damp the excitement which has seized upon us. A little later we reach the edge of the stony tableland, and from this point we look across a broad, large valley penetrating far into the land. Two large rivers still lie frozen on both sides of the valley, right against the high mountains. We barely get a glimpse of some large lakes, the fertile banks of which would surely present a tempting abode for the game we seek. The land shows a grand alternation of plain and mountain, but in vain do we examine with the field-glasses all cloughs, river-beds, and valleys which our eye can reach. Not a living form do we discover, and we return disappointed to our tent.

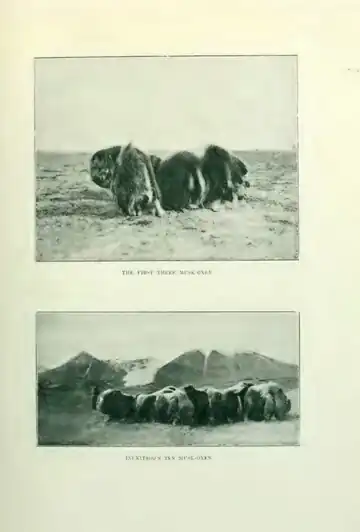

Disappointment always increases a hunter's weariness; we therefore all felt as if we had weights of lead round our ankles when we returned without a catch. Slowly we slid down the mountain without energy in our movements, without spirit as we rushed down the steep snowdrifts. But hardly had we got near the tent before Wulff tore aside the flap, running towards us; Ajako had shot the first musk-oxen on our voyage—three cows! This certainly put new life into us; our tiredness seemed blown away, and we began at once to crawl up the big mountain from which we had just rushed down, and where the hunters were still busy flaying their quarry. I need not describe this beautiful finish to a long day's journey; suffice it to say that we gorged ourselves with tongues and choice morsels far into the night, and that the sleep, which later overwhelmed us and all the sated dogs lying around the tents, was as long as it was well-earned.

We have now to exploit the country through systematic hunts, wherefore we divide into two parties. Wulff, Ajako, Inukitsoq, and Hendrik go in different directions into the great valley which we saw from the mountain yesterday. Inukitsoq had on his hunt found a lot of fresh tracks and excrements in sand and clay. It would therefore appear that the hunters would have an exciting time if only they would persevere. According to this arrangement we should have sufficient hunters for the immediate vicinity, so I myself chose to drive in Victoria Fjord with Bosun, partly for the purpose of hunting, partly so that I might more closely examine the country. We have the advantage of being relatively many, so that in the course of a few days we shall have obtained a perfect survey of the new land. When I mentioned the first disposals for our journey, I emphasized that we could with certainty expect to catch seals some time during the spring, as Eskimos who had accompanied American expeditions in these regions had told of the many breathing-holes they found in places where the ice was young. But we could not reckon on a catch yet, as it was still too early in the spring. Neither could we reckon on finding bears so far north, where the massive quality of the ice would make it difficult for them to find food. We found a track off Cape May, but that was the only one we had so far observed.

During the coming few months we must thus rely upon the musk-ox only, and as, according to the map, the inner reaches of Victoria Fjord contain large stretches of land, Bosun and I hurriedly collected our best dogs and set off before our comrades were ready. Yesterday's meals of solid meat had revived the dogs, and in the beginning we made good speed. We drove into the narrow inlet between land and the tall Stephenson Island, impressive with its steep, exclusive mountains, the inmost regions of which are covered by local glaciers.

We set off in the evening, and in quiet, beautiful sunshine we struggled inland, taking turns at leading. Bosun, a boy not yet twenty years old, had repeatedly shown a surprising capacity for endurance; he had a healthy, even temperament and did not seem susceptible to any kind of adversity, if only he could get somewhere near the rations which his young muscles demanded. He enjoyed his meals very much, and occasionally surprised us with his voracious appetite.

A rather large island behind Stephenson Island is marked on the map, but it proved to be non-existent. Twenty-five kilometres into Victoria Fjord we got the view which we were in search of, and drove into a bay to the west of the big island, looking for a place suitable for a camp, so that the dogs might rest while we, in snowshoes, continued further inland.

We ascended the mountains immediately, and found to our surprise that this fjord, which had previously been described as an enormous arm of the ocean, so deep that one could not even discern the land at its head, is hardly more than 80 kilometres in length. The head of the fjord ends in a broad glacier which, faintly sloping, merges into the inland-ice itself. The great stretches of surrounding land, which the old map promised we should find here, do not exist. Far to the north-east we found land, but it consisted only of steep, glaciated mountains, standing like narrow walls with their backs clean against the inland-ice. Also to the south-west we saw far inland a steep alpine landscape with occasional broad cloughs, but the entrance to this was blocked, as the inner reaches of the fjord consisted of floating inland-ice, slowly moving outward, so that trackless ravines were apparent not very far from our look-out.

This fjord, from which we had expected so much, proved to possess none of the means of subsistence necessary for the accomplishment of our scientific work. Hunting in this country would be both dangerous and futile. We could only hope for better conditions round Nordenskjöld Fjord. We discerned mountains far away to the north-east, but even from the point on which we were now standing, it was obvious that the land would not stretch far in; for the back of the inland-ice shot up all-embracing over the tracts where we had expected land-hunting.

The only place left to us was the big peninsula between Victoria Fjord and Sherard Osborne Fjord, but even this did not seem promising. Although occasional, even stretches with low knolls exist here—a landscape much favoured by musk-oxen—many little local glaciers shot in between them, killing all life.

Our hunt over the surrounding neighbourhood resulted in a bag of two hares, one of which we cooked before, disappointed and tired, we started the long return journey to our comrades, whom with unwilling and weary dogs we reached after an absence of twenty-four hours.

On our arrival Koch came running out of the tent, and his gestures showed us at once that he had good news. Ajako and Wulff had shot six musk-oxen, and all the three sledges had gone out to fetch the animals!

Great joy!

Towards morning—it was one of the first really warm days—the sledges returned with barking, overeaten dogs. Inukitsoq had, during his hunt for hares, met a flock of ten animals right opposite to the six which had already been shot, and which they had come to fetch, and the hunt of the day thus brought in sixteen musk-oxen.

Still greater joy!

At eight o'clock in the evening Koch and Inukitsoq drove in Victoria Fjord for the purpose of charting it.

May 12th-17th.—The welcome meat which we have now collected makes it possible for us to give the dogs the rest which they so richly deserve. They will now be allowed to laze about for a week or so, and to eat as much as they can get down; then they will once more be fit to take up the work which for the time being is interrupted. And these days of good hunting do not merely mean that in the course of a few days we shall again be ready to continue our journey with fit and willing dogs; they also mean that we shall be able to clear up behind us before we continue. For we are now going back to Sherard Osborne Fjord so that we may chart this fjord as well.

To-day we choose a convenient site for our camp, where we can enjoy life at not too great a distance from the killed muskoxen. We drive up the river which runs through the southern side of the valley to the big, beautiful lake on the banks of which the welcome big game had to bite the dust. The tracts round the river and the sea look kind and fertile, comparatively large grass plains stretching across the well-watered spaces. We, who for a long period have been accustomed to barren, stony fields, feel that all this grass dotted with willows is a greeting from the summer, which fights its everlasting battle against the ice.

Here is plenty of excrement of musk-oxen; every stretch of clay and sand bears the imprint of their hoofs, and all signs point to the probability that the killed animals must have lived near this sea for a long time.

Behind the sea the lowland stretches inland as a broad clough-like valley. Wherever the eye rests, stone predominates; but nevertheless it is apparent that the many little rivulets, which during summer-time seem to run down the brown sides of the mountains, water the neighbourhood so plentifully that in the midst of this desert of stone one finds little oases where herbivorous animals can exist. Apparently here is also an abundance of hares, and for the first time since we left the flesh-pots of home we have the feeling that we can eat our fill, without the fear that a greedy appetite shall take too big a slice out of the rations apportioned to each man.

The ice on the lake bears witness that we have arrived in no quiet valley. Along the bank it is bare of snow and shiny, but further in the drifts have been whipped stony hard by sand and gravel. On the snow-bare grass plain we pitch the tents, and it is delicious for once to lie on ground which does not consist of cold, creaking snow. The nearest musk-oxen are being dragged down and the dogs have a meal so substantial that they lie down with big, balloony stomachs, groaning and overgorged, dreaming of the time when there was nothing called expeditions. We men sink into the same materialistic state, but with the difference that we carefully select all the delicious morsels which constitute the chief relish of an Eskimo hunter after a successful catch. Of the killed animals, fourteen are cows and eleven bulls. Round the hearts and kidneys of the oxen we find not a little fat, and also in the hollows of their eyes there are large adipose deposits; this we eat with a specially keen appetite, for the meat we have lived on hitherto has been very lean, and in these regions one's craving for fat is greater than in other places.

The days are raw and cold in the valley, and, although the temperature registered is only between 10 and 12 degrees of frost (Cent.), the wind is unpleasant. There is an incessant drift of sand and stone, and when we go out for meat, our coats are covered with dirty, sandy snow, which sticks between the hairs and is almost impossible to shake off. We therefore decide as far as possible to remain in the tents, where we spend a pleasant day munching.

May 15th.—The 15th of May is uncommonly raw and windy. We bring the last carcases down to the tent, and make ready to go down on the ocean-ice again, where there is more shelter and more warmth from the sun than in these windy quarters.

A couple of the large animals, which were deposited near a mountain from which transport was particularly difficult, were fetched immediately before we moved. On this trip we found behind a big stone a dead musk-ox which strikingly illustrated animal life up here. The musk-ox was a young animal; it had been pursued by a wolf, and in its fear of its deadly enemy it forgot to use its eyes and got its legs squeezed in between two large stones. In this helpless position it was an easy prey for the wolf. With one single snap the thick gristly throat was ripped up, and the rent, as if cut with a blade, went straight downwards through the chest to the diaphragm, which had been torn up with a single wrench of the iron jaws of the wolf. The whole cut was dealt by an expert possessing a certainty in the method of killing achieved only by the habitual perpetrator of violence. Only the tongue, the heart, and the fat round the intestines was eaten, otherwise the flesh had not been touched. There were traces of fox round the spot, but strangely enough it did not appear as if the fox had feasted greatly on the huge carcase; perhaps they prefer the tender and fat lemmings to the tougher big game.

Early in the morning of the 16th of May, Koch and Inukitsoq arrived from Victoria Fjord. Not only had they examined and charted the fjord, but in addition they had had the good fortune to shoot six musk-oxen on the lowlands which Bosun and I traversed in vain. We could not withhold our shouts of joy when we received this news; for beside the charting work of this last fjord, our stay in Nares Land since the 9th of May has resulted in a catch of twenty-six musk-oxen and thirty hares. The survey of Sherard Osborne Fjord now remains. I consider it advisable to set the course southward again as soon as weather permits, and the expedition is divided into two parties: One hunting party, consisting of Dr. Wulff, Hendrik, Inukitsoq, and Bosun, continues northward towards the supposed land round Nordenskjöld Inlet. The charting party consists of Koch, Ajako, and myself. We return temporarily to Sherard Osborne Fjord to finish our work there. But we decide that Hendrik and Bosun shall accompany us in order to fetch part of the goods left at Dragon Point, whilst Inukitsoq drives in Victoria Fjord to fetch the rest of the meat deposited there by himself and Koch. Wulff remains in camp to hunt hares in the neighbourhood until his party is collected and clear for the journey.

In the meantime dirty weather seems to be brewing, and in order not to prolong unnecessarily our stay in this valley of the far too powerful lungs, we move our camp on to a little island at the mouth of Nares Fjord where, at the same time, we deposit all our precious musk-ox meat. Whilst the rest of us drive the meat-laden sledges to the depot, Wulff elects to walk the 5 kilometres across land to the little island which we call Depot Island. Although the distance is short, it took Wulff fourteen hours to find his way through the heavily driving snow. We were unable to search for him, as none of us knew in which direction the hunting might have led him, and great was our joy when at last he arrived with a catch of ten hares.

The hares here appear in big flocks, and are surprisingly tame compared to those we have hitherto met. They are obviously accustomed to grazing with the musk-oxen, and therefore consider man to be just as peaceful as are these huge animals.

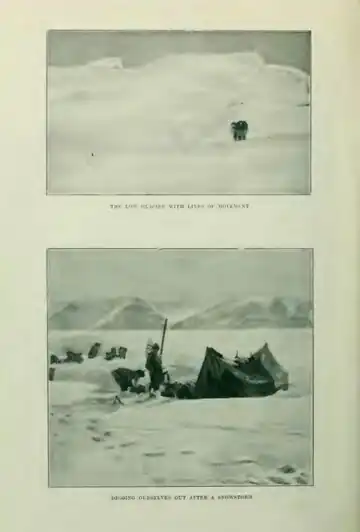

May 18th-19th.—The storm of the last few days has added more than a foot of soft, new snow, aggravating the old and already awkward going on the fjord, so that we now have the "icing-sugar" state of which Beaumont complains in his report. Although the dogs have had eight days' rest, during which time they have been gorged with food, it does not take long before they are again ready to give up. Once more we have to start our old game of walking in front of the dogs on snowshoes and skis, but it is slow work, and progress is made without the good spirit usually attendant on a sledge-train when the dogs trot willingly ahead. We have twenty-two shoulders of musk-ox meat, and these we hope will enable us to accomplish the work which we have decided on. During our stay in the musk-ox valley we have already killed all the dogs which we thought we could do without; for even if hunting has been favourable so far, it is an advantage to have as few mouths as possible to feed in these regions—partly because musk-oxen are very lean at this time of the year, partly also because the bones are too massive for the dogs to gnaw. All our dogs lack the saw-edges of the raptorious tooth, these having, according to the custom of the Eskimo, been removed whilst the dogs were young. This operation is advantageous for the travelling explorer, in so far as the dog is unable to eat his harness and traces when hunger forces him to make such an attempt, for harness and traces are unplaceable during a journey. But, at the same time, it is robbed of the ability to eat very hard bones.

We had fine, beautiful weather, but for all that we did not succeed in reaching the depot in one run. We had to camp right out on Sherard Osborne Fjord, just as we did on the outward journey, and not until the 19th at noon did we reach our old camp.

May 19th.—Immediately before our arrival at the depot we saw to our great pleasure the first seal crawling up on the ice to sun itself; unfortunately it was not killed, although Ajako got very close to it, the bullet passing above its head. In spite of this mishap, the occurrence was of the greatest importance to us. For when the seals begin to crawl up through the old thick Polar-ice already by the middle of May, we are sure of good hunting here nearer the end of June. Successful seal- hunting in this neighbourhood will simplify our return journey very much.

Twenty hours of hare-hunting gives the very meagre bag of only one animal, for in this neighbourhood the hares are so timid that they run off long before a shot can reach them. Some distance from the camp we found the skeleton of a seal on the shore; it had been caught and eaten by a bear. It thus seems that the bears pay occasional visits here, and it is to be hoped that we may succeed in meeting one of these wandering fellows.

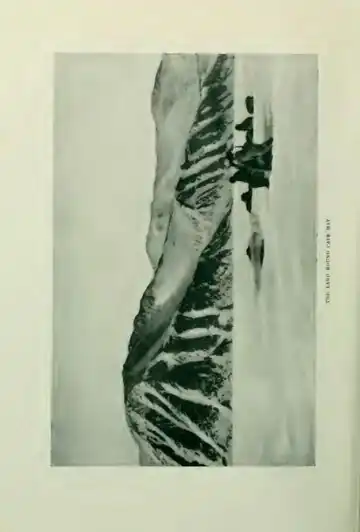

While Hendrik and Bosun drive back to Depot Island, the rest of us make the last preparations for the journey into Sherard Osborne Fjord. First, however, we watch their start. Slowly, very slowly, the dark figures move across the ice. The snow is deep and so loose that the sledges sink into it in spite of the skis. The dogs sink down to their bellies, dragging their tails behind them.

For a long time we hear across the quiet fjord the drivers desperately shouting to the dogs.

May 20th-22nd.—The ice in along the fjord proves to be better than we expected, and for the first 20 kilometres we could drive at a loitering pace without an outrunner. Six kilometres from Dragon Point we again see a seal. Unfortunately we do not get within shooting distance, as it heard us before we caught sight of it, and plopped down through its breathing-hole as soon as we stopped in order to attempt to creep up to it.

We pass the tall, beautiful Castle Island and get 30 kilometres into St. Andrew Bay, as further in the snow gets deeper, absolutely unnerving the dogs. The ice here is very uneven and has the characteristics of floating inland-ice. East of Castle Island we come across a couple of large pressure-ridges running at right angles on to land, parallel to the glacier; this indicates that the ice, even so far out as this, has been under the pressure of the main glacier itself.

At nine o'clock in the evening, Koch and Ajako go into the mountains with a theodolite to take the bearings of St. George Fjord. At three o'clock in the morning they return, having had a view of the fjord, discovering large snow-free land behind and to the south-west. They have also seen an evenly sloping glacier which, between a couple of large mountains, seems to have an even and good connection with the main glacier. This observation further strengthens my resolve later on to try an ascent from this vicinity, when the return journey will sometime lead us on to the inland-ice.

Ajako has shot two hares, which constitute a delicious evening meal and enable us to save the musk-ox meat for the dogs. We have only brought one single, though abundant, ration for them, depositing the rest at Dragon Point for the return journey.

Shortly after the arrival of my comrades two snow-white wolves are silhouetted high up on a hill-crest. Their slender bodies show their plastic beauty against the sharply-blue sky, and they look quite anciently Norse as they trot down towards our camp, sniffing and scenting, full of wonderment.

They stop suddenly by the ice-foot about 500 metres from our tent and follow for a whole hour, thoroughly examining the trail of Koch and Ajako, trotting up and down, now and then stopping to sniff. Then they lift their heads and howl long and persistently, a strangely melancholic and lonely-sounding song of lamentation, which echoes between the mountains. Our dogs prick their ears and look landward in surprise, as if they heard well-known but forgotten tunes; they arise and stare searchingly towards the mountains, but they do not join in the chorus. As the wolves do not appear to wish to come nearer, Ajako approaches them with gun and a dog, a small, lean bitch which has previously shown itself to be a good bear dog. One of the wolves, evidently the male, is very large and strong, and its trot is springy and the fall of its feet rapid. The other one seems somewhat frailer, but nevertheless it is more sinewy than a dog. As soon as the little white bitch catches sight of these rare beasts of prey, which have the same colour as itself, it rushes barking to the land, with tail erect, ready to attack. But the big, silent hermits, which are so much stronger and in full possession of their knife-sharp teeth, put their tails between their legs and flee cowardly in among the mountains. They both have blood on their chops, and have presumably just been feasting on musk-ox meat; a smaller animal could hardly have smeared them so extensively with blood. An hour later the little dog returned, steaming with heat, but apparently disappointed over the lost opportunity of an open fight.

It is six o'clock in the morning when we go to rest after a long day full of events.

On the inward journey travelling conditions are yet more difficult; the uneven ice and the snow, which becomes deeper and deeper the further we go, take the strength out of the dogs to such an extent that I decide to abandon driving and attempt to continue on skis. We make a halt by a headland and shoot. four of the slackest dogs. After this, we give the remaining dogs a feed of musk-oxen. The original decision was to continue inward at once, but this has to be given up, as Koch is so exhausted after several days of diarrhoea that he has to rest: furthermore, Ajako has gone snow-blind. Thus the distance covered during the day is only 10 kilometres; but then, the dogs were unusually slack and weak. The only encouragement the day had to offer us was the trail of a lemming, which showed that this strong and obstinate little animal had set out on a journey which was to take it from one coast of the wide fjord to the other.

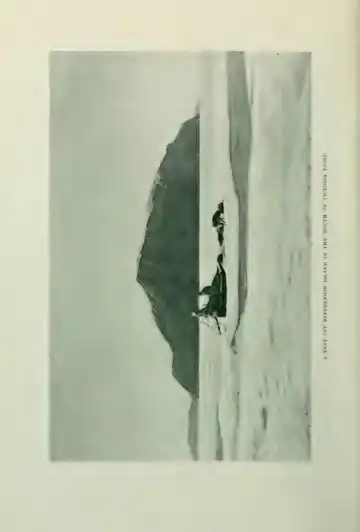

May 23rd.—At one o'clock in the night Koch and I, respectively on snowshoes and skis, begin our toilsome walk through deep snow in towards Cape Buttress, which stands as a mighty signboard on the point where the fjord contracts into a narrow channel, from which it widens out again to a great breadth. Ajako, who is now perfectly snow-blind, has to be left in the tent. The journey is very strenuous and takes us fourteen hours, but it is with interesting results that we return. Sherard Osborne Fjord was marked on the map as the largest of all fjords, as Cape Buttress formed merely the half-way point to the inner widening which contracted here, and later on, in the full breadth of its mouth, swung slightly towards southwest up towards the white inland-ice.

Cape Buttress is a wild and monumental complex of high mountains, the summits of which are covered by a glacier, gigantic and brilliant with red hues, blossoming out under the rays of the sun.

We had followed the coast on the western side rather close to land, and every time we looked eastward we saw a low cloudlike brim which often covered the lower part of the shore. It was like a small bank of fog which, white and trembling, encircled the feet of the mountains. Only when we arrived quite close to the great cape towards which we made our course did we come suddenly out on the fog-bank itself, and we now discovered that the mystery was low-floating inland-ice, reaching right down to Cape Gray on Castle Island. This floating inland-ice, which further out raises itself only a couple of metres above the old Sikûssaq ice, mounts quite evenly inward where, with the real characteristics of a glacier constantly increasing in thickness, it passes Cape Buttress on the inner side. No fissures were apparent, wherefore this ice-stream, which runs out between two beautiful mountain tracts, would present a convenient point of ascent on to the inland-ice itself if one did not run the risk of finding clefts further inland. At any rate, both Peary and Astrup mention that on the main glacier inside Sherard Osborne Fjord they often had to take an inland course to get inside the many broad and deep clefts which blocked their way.

The discovery of this far-reaching tongue of the glacier reduces the extent of Sherard Osborne Fjord to a bare third of what previously it was supposed to be, and at the same time it gives an explanation of the belts of pressure-ice which a few days ago we saw at the height of Cape Gray. This ice-stream, then, is in constant, even movement outward, and thus exerts a pressure on the old Polar-ice, so that the ridges arise in places where otherwise one would not expect to find any movement.

To the south-west of Cape Buttress a fjord cuts in, surrounded by a great lowland ending in a high cape on the western bank. This fjord, with its surrounding land buried in deep snow, we christened "Ski Cove."

When we had completed our survey we turned homeward, and it soon became apparent that Koch, who during these last few days had not been well, was much more ill than I had suspected. A few times before we reached our tent he had to lie down on the ice to avoid fainting, and I am sure it was with the utmost effort that he succeeded in accomplishing the journey, which even for a healthy man is very tiring, as we had continually to toil through the deep snow, which was so soft and fine that neither skis nor snowshoes would carry one.

May 24th.—Whereas the weather was clear with almost a dead calm at the head of the bay where we had been, at the mouth of the fjord there had been strong showers of driving snow during the last few days. The ice was therefore partly blown away, and although the dogs during the last couple of days had to live on their four killed comrades, we had no great difficulty in driving them ahead, as travelling conditions were better.

During the latter part of the journey we met with an adventure which gave us a good push ahead. We discovered suddenly, ahead of us, two white forms slowly approaching. In the beginning we imagined them to be bears, and rejoiced already in our good fortune which would provide us both with food for the dogs and fill up our own flesh-pots.

The big white animals moved slowly towards us and at a distance they behaved just like bears, scenting their way towards the enemy. Hardly had the dogs discovered them when off they flew, all weariness forgotten and the carnivorous urgings, which had so long been suppressed, aroused with a new and unknown force. We rushed across the ice at a speed which we had not found possible since our last bear-hunts. Unfortunately the whole thing was dissolved in deep disappointment when we found that the animals were two wolves which had wandered out on the ice. As we approached them they ran off in the direction which we were taking, and thus it happened that the rest of the distance to our depot was covered at a full gallop.

Our excitement was of course great, as the trail showed that the wolves had just come from the depot where, beside our clothes, we had also left some shoulders of musk-ox meat which were to save our dogs. But fortunately the unwelcome guests had been too cowardly to go right up to the depot, which was quite untouched, though, judging from the tracks, they had been slinking about for the better part of the day tempted by the smell of meat.

May 24th-26th.—The state of the fjord can hardly be worse, and yet it has again started snowing! The tracks which we were to have followed to Cape May, and which would have eased the work of the dogs, are quite obliterated. The position is not encouraging. At our arrival here last night we fed the dogs with the last of the musk-ox meat, and we ourselves have very short rations to live upon if we are not to attack our depot, so far sacred as a reserve for the return journey.

Koch lay down immediately after our arrival, and all through the day he has had high fever, which has further enfeebled him. He is in a bad way, though some improvement is noticed towards evening after a good sound sleep. However much we wish to get away from this place, which offers no possibilities for existence, I dare not continue with Koch in his present state. We must therefore kill more dogs and calmly wait for better times. The snow sings softly but uncannily on the canvas; it falls in fine, close flakes which for every hour that goes make travelling conditions worse. But the mood consequent on these happenings, when everything seems to go contrary to our wishes, finds a natural outlet in a little verse of Sophus Clausen:

The following day we have to lie up again; the weather clears up beautifully, but although we make repeated excursions inland we find no game. Neither does any seal crawl up on the ice, so to-day we have to shoot three dogs—three poor, lean dogs.

With a heavy heart I have to shoot old Miteq—"the Eiderduck"—the oldest one in my team; a patient and industrious animal which dragged until it tottered with exhaustion between the traces. It was probably the most faithful one in the team, therefore the most worn-out and the one which, with its skinny carcase, must serve to satiate its comrades.

Poor Eiderduck!

I would fain have given it a safe return and an old age free of cares. Through Hall Basin and the destructive pressure-ice of Robeson Channel, across the heavily gravelled ice-foot between Cape Brevoort and Cape Bryan, and at last through the bottomless snow of Sherard Osborne Fjord, it has worked patiently and steadily. It reached Nares Land and ate as much as it could manage of delicious musk-ox meat. But then it had to turn back once more through the trackless country. It was a mute but willing worker in the service of exploration. Always industrious, it dragged to and fro with its stumpy tail straight up in the air; but just as I was ready to set across to our meat store, illness claimed it—a sacrifice for the benefit of its mates.

Therefore let the old dog take these memorial words with it in its painless death. A Winchester bullet pierced its temple. I have just flayed it, and yet, whilst I am scribbling this in my diary, the strong, sickening smell of its blood clings to my fingers.

As shortly afterwards I go out to feed the dogs, I find that old Miteq had no significance at all as food; there was no flesh on it—it consisted of skin and bones only. We therefore had to kill another two dogs—altogether five carcases—to feed the rest; for on all the slaughtered animals there was scarcely any nourishment.

It is a disgusting work, fit only for an executioner's assistant, to flense these animals, and that not least because they were good dogs which should have worked for us yet awhile if only we had been able to get on quicker to better hunting-grounds.

On the evening of the 26th, Koch's condition seems so much better that we dare to cross the fjord. We make ready to break camp, and a new report is deposited in Beaumont's beacon. We have to give up the idea of letting Koch drive his own sledge, as I fear he has not the strength to do this; it is hard and laborious work to drive the dogs forward, and the cannibal food which we offer them agrees so badly with them that they often vomit. Ajako and I therefore share the rest of Koch's team between us.

The dogs are so exhausted that we can hardly hope to be able to ride on the sledges, wherefore Koch sets out a few hours before the rest so as to get somewhat ahead of us. When later on Ajako and I set off with our melancholy animals, we leave this headland, which now stinks with the gnawed bones of dogs, with a sigh of relief.

May 27th.—Slowly, slowly, we struggle ahead 2 kilometres to the hour, the dogs, with hanging tails, ready to drop whenever a slight ridge hampers the sledge.

For the first four hours we crawl along through a clammy fog surrounded by greyish-white thickness on all sides; nothing to see, nothing to steer by, like blind men we struggle along in the white gap, and the monotony makes our advance still more miserable.

Suddenly the sun appears as a huge white ball through the fog; in the zenith the sky bursts forth, breaking through the clouds like blue unfolding flowers; and now the sun follows up its victory, whilst the edges of the clouds begin to glow, and soon the close blanket of fog trembles under the beams of the great heater.

The white tops of the country round Cape May break through ahead, first the cone-shaped Fusjijama (Mount Hooker) and then the rest of Beaumont's Mountains, Mounts Coppinger and Farragut, still paddling with their feet in the fog; soon the ice bursts into transparent silver ribbons, hovering like narrow wisps of smoke over the lands, promising good weather.

And so the most glorious Whitsun weather drove in to Sherard Osborne Fjord with clear sky and calm warmth.

At five o'clock we had to stop, as the dogs could endure no more; we made camp, hoisted our flag, and commenced our day of rest. A festive Whitsun, with a solemn mood which the mountains and the white snow communicated to our minds. . . .

It is 10 degrees of frost (Cent.), but the feeling is that of a hot August day in Denmark, and with the warmth in our hearts which all this grand beauty generates we celebrate Whitsun according to our poor means.

We make tea, and drink it whilst we suck fruit-drops, and with the taste of red currants and cherries on our lips our thoughts involuntarily turn to home—the long, long way, almost across the whole globe, to the vicarages in Sealand, which in this moment lie like islands among the trees' green drifts and flowering fruit-trees. We sense the fragrance of flowers, we hear the songs of larks and nightingales, the contented lowing of cows in the meadows, and the happy laughter of merry people celebrating Whitsun in the shady beech forests.

And we sit here in an ocean of light which blinds our eyes, in the midst of the winter-white Arctic spring, with pure new snow round our feet, the sun-gilded horizon of the glaciers behind the russet mountains, and the cold, bound Polar Sea before us lonely, wandering explorers, with a whole world between us and our relatives and friends.

Yet we celebrate the day, and with a longing for the fertile south which has so often given nourishment to our thoughts up here on the skull of the world, we eat, materialistic as always, a tin of Mauna Loa, the only one we possess, tinned at Hawaii and exported from Honolulu; and as we see before us the dark-eyed, garlanded girls who picked the fruits, it is as if we cut through all horizons and conquer the world.

Hawaii and the Polar Sea, N. Lat. 82°!

So we cook the musk-ox meat from Nares Land, drink coffee from Java after the tea from the Congo, and smoke tobacco from Brazil!

A glorious Whitsun!

In spite of our efforts, we do not succeed in covering those poor 55 kilometres from Dragon Point to Depot Island in less than two days. We have had to drive slowly out of consideration for the sick Koch, who is as yet so poorly that he cannot manage long stretches in one run. It seems he cannot stand the complete diet of meat to which we up here are confined; during the marches weariness and sudden dizziness overwhelm him so that he has to lie down to prevent himself from falling. Fortunately, he takes his illness calmly, and, thanks to his young, strong constitution, he resists it so stubbornly that we are not very much hampered. He refuses all offers of a halt near McMillan Valley, and, as he himself is of the opinion that he is strong enough to continue, we take the shortest possible rest, as hunting conditions force us ahead as quickly as possible.

The hunting here has been successful beyond all expectations, but we must be careful lest the good result mislead us. For, after all, the ice-free country is only small in extent, so that only a limited number of big game will be found in the immediate neighbourhood, and the point is not to exhaust the district entirely. In all probability we shall return at some time, and we would have to pay dearly later on if on our outward journey we let things slide and did not offer a thought as to future emergencies.

Just behind Cape May we see six hares; two of them we shoot, whilst a cup of strong tea is made to give us strength for the last stage of the journey towards the little island where we have deposited two rations of musk-ox meat for every team.

There seem to be many hares here, but we dare not depend to any great degree on this game. The animal is too small and also too bony, and it does not go sufficiently far as provisions on a journey on the inland-ice.

The dogs scent our meat depot far away and we finish the journey at a merry trot, which is quite stimulating although one knows that the cause of the speed is an artificial one. For a moment we are seized by a nervousness easily understood when we discover that tracks of foxes lead to the depot. Fortunately, Reynard has been too careful, or perhaps not hungry enough, to attack the meat, which we find quite untouched. We can now finish our journey with a really solid meal which is as well deserved as it is necessary.

On our old camping-ground we find a hare swinging at the end of a long stick which has been rammed down in the snow. We run up full of curiosity to see if, maybe, other precious things are hidden in a tin placed on the same spot, and in which we find a letter from Dr. Wulff, who very funnily tells of his party's experiences during the time we had been separated.

On the following day, the 29th of May, we reach Cape Wohlgemuth through the same heavy snow which we have hitherto met on the fjords; the downfall seems to be sufficient here, but little wind. In spite of the trail of our comrades, which is of great assistance to us, it takes us eleven hours to cover the distance of 29 kilometres. Here by Cape Wohlgemuth we celebrate this high-spirited name by giving our dogs the last meat we possess. During a short ski excursion we find on a ski-staff another letter from Wulff with the information that on this spot they have shot a musk-ox.

Next day at noon we reach our comrades, who receive us with storming shouts of welcome. They have again shot six musk-oxen, a heaven-sent gift for our hungry dogs.

Yesterday Harrigan tried to hunt in Nordenskjöld Fjord, but returned quickly, as he saw at once that the country was no good hunting-ground. He found everywhere tall, vertical mountain-walls; the few cloughs which ran across the great compact chains of mountains were stony deserts without vegetation. He did not go far inland, and we, who wish to keep as long as possible to the tracts marked on the old charts, are hoping that the fjord may be so deep that at its head we may find land and game.

However, one matter must be decided on at once. According to our original plan, a permanent headquarters was to be made by the head of Nordenskjöld Fjord, where the botanist of the expedition during our wandering life was to make his observations in peace. Hendrik Olsen, Harrigan, and Bosun were to remain with Wulff, and were to hunt in preparation for our journey homewards; while Koch, Ajako, and I were to cross over to the land of the big game and Nyeboes Glacier, and then via Independence Fjord go north of Peary Land, calling at Mylius-Erichsen's beacon on Cape Glacier, at Koch's beacon near Cape Bridgeman, and at Peary's beacon near Cape Morris Jesup. After the lapse of a good one and a half months the members of the expedition were to meet again off Nordenskjöld Fjord to start the return journey together.

But after Inukitsoq's sledge journey in the fjord the plan of the botanic stations has to be given up, and we decide to divide the expedition into two parties, with the following tasks:

One hunting-party must immediately go northward to de Long Fjord to hunt for musk-oxen in the district northward up to Cape Morris Jesup. Dr. Wulff accompanies this party so that he may see as much as possible of the coast.

But Koch, Ajako, and I must go in to the head of Nordenskjöld Fjord, chart this, and then across the inland-ice go towards the hunting districts round Poppy Valley, then through Independence Fjord north of Peary Land.

All these plans were discussed in the best of spirits whilst our comrades tried to tickle the palates of us, the last ones to arrive, with every possible delicious morsel from the newly-killed animals. The subjects of our conversation seemed to be inexhaustible after our twelve days of separation, and as we had to go each in our own direction on the following morning, our meeting was a hearty one which I shall always remember.

Our position would be a serious one if hunting should fail hereafter, and we had yet a chance to run away from the fight and return home. For although there was yet the possibility of seal-hunting, which might provide us later on with meat, the chances in the midst of all this old Polar-ice were so uncertain that we could not be sure of success. On the other hand, if we were to save our skins by going southward now, our work would only be half accomplished, and no one approved of this solution of the problem. When we left we all knew the risks we ran, and the position was already now such that our lives were at stake in the accomplishment of our task. To my great joy there was not one of my comrades, neither among the scientists nor among the Eskimos, who for one single instant doubted what we had to do.

Everyone agreed that the expedition in the face of all odds ought to continue, and not one would give in until we had kept the promises made at the time when we left Denmark.

Through 1 metre of deep soft snow we drove slowly in the fjord, whilst our comrades set their course towards Cape Salor, where they expected to find a depot from Peary's time.

We did not succeed in penetrating the fjord more than 17 kilometres, and at this point, early in the morning, we camped off a broad clough which cuts into the country. Here Ajako tried musk-ox hunting. For eight hours he tramped across the country, but all he saw was stones, stones, and glaciers along all the mountain-tops. Not a trace of musk-ox or hare was found, not even ptarmigan seemed to live in this desert.

When he returned with his discouraging report, the fog settled thickly over mountain and ice, and there was nothing else for it but to settle down to wait and wait, with short rations for ourselves and nothing for our dogs. On the ice near the tent I found a dead lemming. It had walked across the deep snow from the other side of the fjord. The energetic and obstinate little animal appeared to have been wandering through the fog, as occasionally it had been walking in a circle, and had moved along in an uneven zigzag which showed plainly that it had lost its bearings. It was almost incredible that this small rodent, which is no larger than a fair-sized bunting, had managed to make its way through the deep snow, of which the upper layer was so soft that it had had to press its small sinewy body through a deep and assuredly most toilsome furrow. All its paws were skinned, and so torn that the toes were frozen together with stiffened blood. The snow had, presumably in the same manner as it happens with our dogs, stuck to the hairs between its toes; then it had made an effort to try to cleanse them with its teeth, so that it had torn both hair and skin away. In one foot it had a deep wound which it must have inflicted on itself, and the consequent loss of blood must have occasioned its death.

The Eskimos, who admire the unusual qualities of the lemming, its courage, its endurance and stubbornness, say of it that it possesses the chest of a man, the beard of a seal, the feet of a bear, and the teeth and tail of a hare—a characterization of its appearance which is very striking.

On the 2nd of June we must kill another four dogs, as we are continually unable to find food. Ajako and Koch now drive a team of ten dogs and I drive one of seven; and although this is yet a fair number, we need to be careful not to kill many more for the time being. For if we are to drive and not to walk on the return journey, with our collections and the food for our dogs, we ought to have four sledges with seven dogs in each team. The six musk-oxen which were killed by the mouth of the fjord provided only three meals a team for our forty-four dogs. We therefore decide to leave two rations at our old camp, so that we shall not be quite without dog food when we return later on to cross over to Chip Inlet.

In spite of the unfortunate hazy weather which we have had, we have succeeded in examining Nordenskjöld Fjord, for a fresh breeze has now and then lifted the clouds aside and given us the necessary view. The nature corresponds on the whole to what we observed round Victoria Fjord. The surrounding land, with the exception of the quite small and barren brim along the shore, is covered with glaciers; and the fjord, which ends in broad inland-ice, but behind which one can discern Nunataker, is hardly more than 20 kilometres long. The extent depends somewhat upon one's decision as to where the oceanice proper is relieved by floating inland-ice. Five or six kilometres inside our camp a big bank of ice-mountains shoots right across the run, so that the passage is entirely blocked. As these ice-mountains to a height of from 3 to 6 metres stand closely by the main glacier itself—with deep snow in all crevices and apparently being moved by the glacier just as is the floating inland-ice in Victoria Fjord—one may decide that the real fjord ends here. These ice-mountains make the passage further ahead impossible. Thus no accession to the inland-ice is possible from this point, and it follows as a matter of course that we must give up every thought of pushing through to Independence Fjord. We can find neither the road nor the provision for this purpose.

As soon as Chip Inlet has been explored, we must speedily set off after our comrades and then, later on when de Long Fjord has been charted, set the course south towards the seals by Dragon Point.

Our geographical discoveries have been very interesting up to now, and it is already obvious that the relation between inland-ice and coastland should be marked out in an entirely different way for that part of Greenland which we have now traversed. We find everything is glaciated to a far greater extent than we expected, and although of course it is the task of every expedition to bring home as much new information as possible, I cannot deny that, for our own safety's sake, we might have wished for fewer corrections of all the lovely extensive hunting-land which has up to the present been marked down on all the American maps.

Again to-day we see a lemming attempting to cross the fjord. It comes from the clough close by our camp and stubbornly sets its course where the crossing is at its broadest. In comparison to its size it shoots ahead with dazing speed, swimming through the snow with queer jumps. Occasionally it disappears entirely in a tunnel to shoot up further ahead like a dwarf seal coming up to breathe. With its weeny size and its phenomenal energy, it seems paradoxical in these enormous surroundings which swallow it up.

One of our dogs scents it and rushes up so violently that the traces break. In the same instant a cloud of snow whirls up round the trail of the little wanderer; for a few seconds yet the lemming fights its way ahead, then suddenly it is flung high up in the air to disappear still alive into the mouth of the dog.

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)