Greenland by the Polar Sea/Introduction

INTRODUCTION

IN the year 1910, at North Star Bay, in North Greenland, I founded an Arctic Station wherefrom I could explore the regions which as yet had not been closely examined. The first result from this station was the first Thule Expedition. The various expeditions which subsequently went out with this station as their base I have therefore named after the station, Thule.

On the first Thule Expedition in 1912, when the route was laid across the inland-ice of Greenland from Clements Markham Glacier in the mouth of Inglefield Gulf on the west coast to Denmark Fjord on the east coast, we forced our way through Independence Fjord into the land connecting Greenland and Peary Land, and by charting we established that the channel which Robert E. Peary thought he had discovered between Independence Fjord on the north-east side and Nordenskjöld Inlet on the north-west side was non-existent.

Because of the long journey, more than 1,000 kilometres across the inland-ice, and the conditions which made progress difficult in the neighbourhood of Denmark Fjord, we did not succeed in pushing quite through from the recently discovered Adam Biering Land to the vicinity of Nordenskjöld Inlet and Sherard Osborne Fjord. At the time when the decision to commence the return journey was made we had spent more than four months of incessant and very strenuous journeying through unknown regions, and out of consideration both for. ourselves and our dogs we found it necessary to attempt the homeward journey across the inland-ice to my station Thule by North Star Bay, and postpone the exploration of the unknown districts of Greenland until the time when the work could be recommenced with renewed strength.

In the winter of 1914 the first attempt to realize our plans was made, with Peter Freuchen, my cartographer of the first Thule Expedition, as chief; but a fall through a glacier crevasse during the ascent on to the inland-ice forced him to turn back, and later on, owing to his theodolite having been destroyed by the fall, it had been impossible for him to get away.

Meanwhile this expedition stood like an unredeemed pledge from my Arctic Station, and as, for various practical reasons, it must be finished with before I commenced my ethnographical voyage to the American Eskimos (the fifth Thule Expedition—the Danish Expedition to the Arctic North America), which would last several years, I decided to make an attempt to realize it in the year 1916.

It will be the main object of this expedition to survey and chart the last unknown reach of Greenland's north coast on the stretch between St. George Fjord and de Long Fjord. We shall, of course, with special keenness penetrate into the connecting land between Nordenskjöld Inlet and Independence Fjord.

The survey of the districts to which we are going will, in addition to the geographical result, present very interesting ethnographical problems, as it will be of importance to the theory of the Eskimos' wanderings to establish whether or not in the above-mentioned big fjords Eskimo winter-houses are to be found. As is known, tent-rings have been found in Peary Land, but never winter-houses. The northern border of the winter-houses is, on the east coast of North Greenland, Sophus Müller Point and Eskimo Point, respectively in Amdrup and Holm Land, whilst the northern border on the west coast is the vicinity of Humboldt's Glacier and Lake Hazen in Grant Land. Thus, for a complete knowledge of the Eskimos' wanderings, an examination of the great fjords on Greenland's north coast is wanting.

Of the geological tasks which the expedition may be faced with, I will merely mention the following: Whilst the whole of Western and Eastern Greenland during the last century has been geologically surveyed by various expeditions, the stretch from Sherard Osborne Fjord to Peary Land, with the latter's unknown fjords, still stands as the missing link between the east and the west coast; until these regions have been examined no complete picture of Greenland can be formed. And just as the coasts and fjords up here at the northern extremity are still waiting to be charted, so the keystone of the journeys of geological exploration can only be laid through an examination of these regions.

In addition to the work which I have now outlined, careful meteorological diaries will be kept during the whole of the expedition, and botanical and zoological collections will be made.

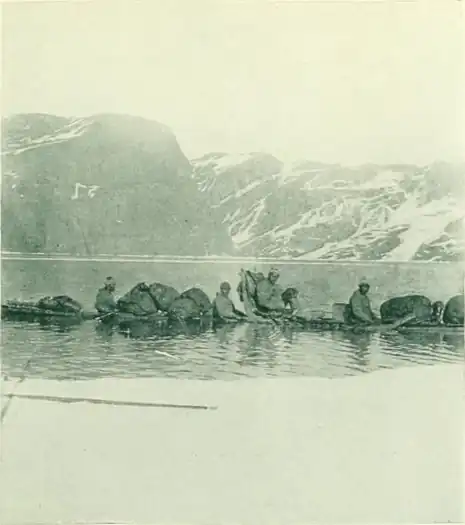

This expedition, as the first Thule Expedition, will throughout be equipped in Eskimo fashion, so that we can live by hunting whilst at the same time we attend to our scientific interests.

The expense is met by my station Thule, which is controlled by a committee consisting of—

- Ingeniör M. Ib. Nyeboe, Chairman.

- Grosserer Chr. Erichsen.

- Lektor Chr. Rasmussen.

The scientific work which is being done, and which also in the future will be done, from this station has made it desirable that we should be in more direct communication with scientists, wherefore a scientific committee has been formed, consisting of—

- Professor Dr. phil. H. Jungersen.

- Kaptajn I. P. Koch.

- Professor O. B. Böggild.

- Professor H. P. Steensby.

- Museumsinspektör, Dr. phil. C. H. Ostenfeld.

Originally I had intended to undertake this expedition with only one companion, the Danish geologist Lauge Koch, M.A. We left Copenhagen on the 1st of April, 1916, and reached Thule by the middle of June, but continual storms and uncommonly difficult travelling conditions forced us to postpone the journey until the following spring. Meanwhile, in the course of the summer the old expedition ship the Danmark called at my station on its way to Etah to fetch the American Crockerland Expedition, which for several years had wintered there. On board this ship was a Swedish scientist, Dr. Thorild Wulff, whose original field of labour comprised only the districts round Smith Sound and Melville Bay; but when Dr. Wulff heard that we had postponed our expedition until the following year, he announced himself with great enthusiasm as a fellow-member for the sledge journey in the spring.

His name as a botanist, and his expert knowledge of the Arctic flora, made it a matter of course that he should be accepted as a member of the proposed expedition to regions which had never been visited by experts.

The expedition then wintered at my station Thule, being constantly in training by sledge journeys, which reached to Etah in the north and right down to Upernivik in the south. It will merely lead to a repetition of the experience of other expeditions if I describe our excursions during the period whilst we were waiting for the light—that is, from October to February. And as it cannot be presumed that all who may read this book know anything about the Polar Eskimos, I will instead attempt to give a sketch of the people whose ways of finding a subsistence and whose travelling technique was the base on which we built our great journey.

With occasional breaks I have lived with this people—the Arctic Highlanders—since 1903, and I have learned to love them as highly as I admire their remarkable ability to live the life of these harsh regions. But first it will be appropriate to give an account of my expedition and its plan.

The scientific equipment of the expedition was very simple—as is necessary for a long sledge journey. It consisted of one theodolite, three aneroid barometers, one cooking barometer, one maximal and two minimal thermometers, various spirit and mercury thermometers, one anemometer, and one hygrometer. Finally, Dr. Wulff brought everything necessary for pressing and preserving plants.

During the preparations for this journey, the seriousness of which none of us under-estimated, I made out on the 14th of February a written agreement which was signed by all. Only the following extract will be of interest, the remainder relating to routes and dispositions which will be self-evident later on:

"Although it is quite clear to me that it is very difficult previous to a start to specify an Expedition in sections, I have found it necessary to do this so that you, my comrades, may have some fixed point for the planning of the various parts of the work to be carried out.

"The Expedition will consist of—

- Dr. Thorild Wulff, Botanist and Biologist.

- Lauge Koch, Geologist and Cartographer.

- Hendrik Olsen, previously a member of the Danmark Expedition.

- Ajako.

- Nasaitsordluarsuk, called Bosun.

- Inukitsoq, called Harrigan.

- And myself, as Chief and Ethnographer to the Expedition.

"In a previously presented plan all the tasks have already been worked out.

"As regards dispositions of journeys and routes I am absolute Chief. But I will, of course, within the domain of your respective professions, grant you all the freedom which circumstances may permit, and you will also, as often as your work may demand, be exempted from hunting.

"I wish beforehand to emphasize that during the Expedition there must be no difference in standing between the Eskimos and ourselves, the Eskimos being members of the Expedition with equal rights and duties to the scientists, and no man but the leader must have command over them."

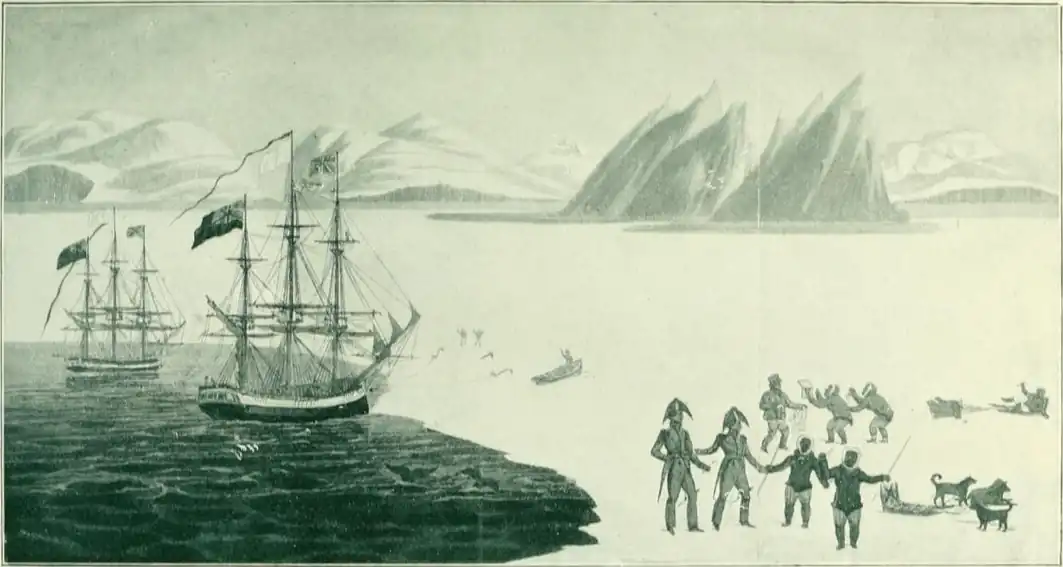

Several large expeditions richly equipped had already been to the regions we were to visit; but none of them had succeeded in acquiring a thorough knowledge of the country—this despite the fact that due to its position it must contain the key to many problems decisive for the exploration and history of Greenland.

The explanation is this: The distances between the fields of labour are immense; the conditions of the ground are bad; and in the fjords there is bottomless snow. For these reasons those who have visited this district with what is called good equipment could not get ahead. Their heavy baggage did not permit them to get about, and they always preferred to follow the route along the Polar-ice proper, some distance from land, where the going was firm.

In other words, that which under all other circumstances was to be looked upon as a decided advantage, rich and good equipment, is here a weight which does not permit the explorer to move as quickly as the travelling season demands.

Those who were to attempt the completion of the charting of Greenland must therefore break entirely with the general practice of expeditions, and completely rely upon the hunt. Only this will make light sledges capable of forcing their way through the snow into the deep fjords.

Thus for us there was no alternative. All the tasks we had set ourselves were weighty and important, and as long as they remained undone the exploration of Greenland could not be considered accomplished.

This work fell within the International North Pole route, which hitherto only the big nations had dared to attempt.

The outlines of our work, however, were drawn by our predecessors, and we therefore knew beforehand that we could not expect any great geographical surprises; it was only the crumbs from the table of the rich expeditions we were to gather, and the rôle we were to play would be comparable to that of the little Polar fox, which everywhere on the Arctic coast follows the footsteps of the big ice-bear, hoping that something good may be left for it.

But our task was not an ungrateful one, for we came to lift the stones which the others had let lie.

From our base at Thule the distance we had to cover to Sherard Osborne Fjord was 1,000 kilometres, whilst our predecessors, with their ships in winter harbour in Lady Franklin Bay and Cape Sheridan, had merely had to go 300 kilometres. For the above-mentioned distance we would have sufficient provisions, but after that our hunt for food must begin.

The experiences I had gained in 1912 during the first Thule Expedition gave me the right to assume that such a plan could be justified. The game I particularly reckoned on musk-ox, to be found in the extensive tracts of land which the American maps show round the fjords and their heads. Further, there were seals. The Polar Eskimos who, during Peary's expeditions, had traversed the mouths of the fjords, had told me that the ice here was of such a quality that one could with certainty reckon on seals in June and July; breathing-holes were not infrequently observed. This information, added to my own experiences from Independence Fjord, where in a similar geographical position we found many seals, finally decided me.

The risk one runs on such hunting expeditions was quite clear to me; but the mind never occupies itself with the dangers when one is setting out. Every Polar traveller is aware of his risks when he leaves his home to set foot on unknown shores; and thus it was also with us. All my comrades greeted my plans with enthusiasm, and every man was inspired with one thought only the certainty of success.

KNUD RASMUSSEN.