Grim Grand Manan

Grim Grand Manan

YES, even in these days, years since the Ashburton Treaty was signed to the dissatisfaction of two nations, the Maine Yankee walks out to the peak of West Quoddy Head—easternmost nubble of the main of our Land of the Free— points his thin nose in the direction of the wind-blown cliffs of Grand Manan, and allows "that the island ought - to belong to us." If it did belong to us, Yankee acquisitiveness could stand on the cliffs of the main and gaze out over several leagues of tossing sea at bare, brown, towering precipices, and boast that the United States had thrust its independent nose into the waters of the King to the extent of an island twenty-one miles long and six miles broad. That boast, it is to be feared, would be about the extent of the interest any Yankee would take in Grand Manan, Ask the lifelong citizens of Eastport or Lubec— Yankee communities less than twenty miles from the island—if they have ever been on Grand Manan, and almost to a man they confess they have not.

Grand Manan turns toward the main a broad and forbidding back of lose cliffs The great shoulders of North Head are hunched in surly fashion. The coves, the reaches from the sea, the valleys, the

patches of arable land, face the ocean and invite the mariner. For the Yankee on the main only the bluff, brown back— like the shoulders of a sullen old man under a sun-tanned coat!

That old story about the manner in which the American commissioners were fooled at the time of the Ashburton Treaty persists on the eastern border; it has settled into something like grave fact. You are told that some limpid and well-aged stimulant was employed to mellow the contfabulations between the commissioners and insure the amenities of international discourse; that the

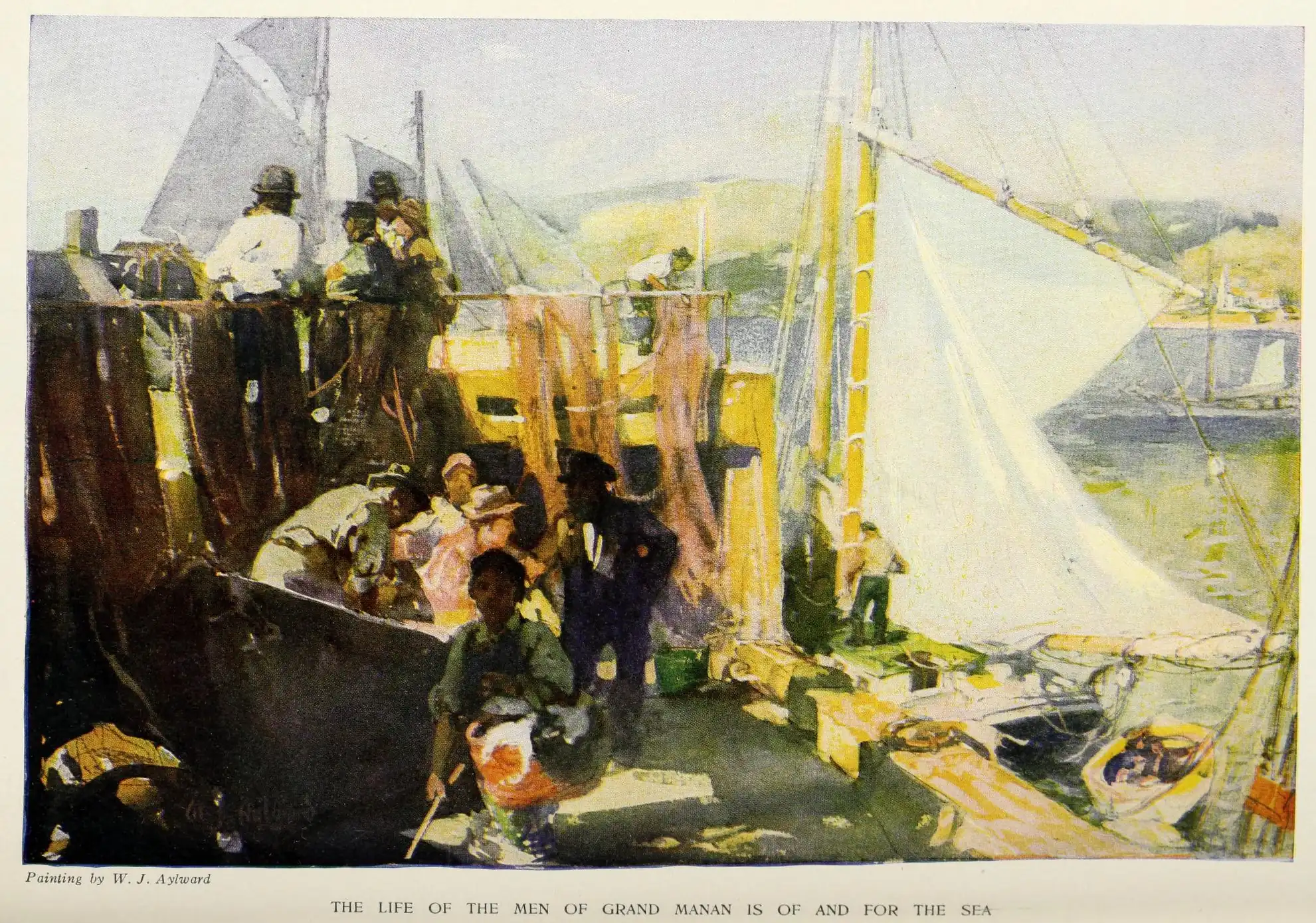

Painting by W. J. Aylward

The Life of the Men of Grand Manan is of and for the Sea

from the vast stretches of water under the vaulted sky.

We surged in from the sea, past Swallow-tail Light. The British Jack on the headland was smeared against the clouds by the wind, as hard and stiff as the tin flag of a toy-soldier encampment. The wind does blow at Grand Manan!

“It’s a venturesome trip at any time,” said the skipper of the motor-packet. “If it doesn’t blow when you’re coming out here, it’s sure to blow when you’re going back, and that’s why the resorters haven’t spoiled Grand Manan with their flounces and airs and notions.”

The winds of Grand Manan refuse to he cajoled by any promoters of summer colonies. There is, first of all, the joyous wind from the northwest, tingling even when the sunshine of August is melted into it. That wind beats frothy ara- besques against the looming brown cliffs and sends a tide-rip streaming from North Head five miles across to The Wolves—-a rip that is operated by a twenty-eight-foot tide sweeping through the jaws of the Bay of Fundy. It is a rip where the waves chase and dodge and double back on themselves with most fantastic contra-dance—building sudden pinnacles, scooping unexpected valleys in the green water—and many a little boat has been tripped by a high-sided comber or engulfed by a leaping crest. Though the sky be glorious, its arch of pale velvet swept clean by that joyous gale from the north; though the sun may shine and the ocean may flash its glories of silver light, yet there is ever that bar- rier of the Nerth Head rip to cross if one wishes to enter into the placid life of isolated Grand Manan.

The east wind sweeps in vast seas that climb the cliffs, and the south wind rolls up the sea with arms heaped high with fog. One may not determine when he can land on Grand Manan; one ean- not say to himself, “ Lo, I will arise and go!” The winds may be pushing the scenery of sea by him too rapidly for a summer-resorter’s nerves and courage.

The tides race, the winds gallop, the lofty schooners and steamers of the Province traffic hurry past Grand Manan. All that haste seems to make the island especially inert, stolid, archaic, and non- progressive.

But Grand Manan may deceive by that aspect. Its first automobile is now frisking along its twelve miles of road!

“Tve got one horse wonted to the thing already,” says the livery-stable man. “I ean let you that horse and voull be middling safe, though you’ll have to push on the webbin’s pretty hard to get there quick. If you want to go faster, Ill have to take another horse and drive him myself to be on the safe side.” ’

This was not on a Sunday. No; one eannot hire a horse on Grand Manan for Sunday use. One cannot lark or play or buy any goods or drinks or papers on Sunday on Grand Manan. The rules and customs were not imported from Blue Law Connecticut. They eame from the Province with the Seoteh disposition which has flavored the stock of men on Manan.

Though the island braces itself against the racing tides, the inhabitants do not resist progress of any sort which seems vroper to them. <A cable brings a tele- phone from the main. There is an ama- teur wireless outfit. ‘There are two banks for the savings of the thrifty—and all the islanders are thrifty. Everybody knows the latest news of the world. And when we asked for dinners for four at the tavern the buxom landlady replied: “Sure! I got you, Steve!”

“The other hotel has closed,” she said.

“Tt was a larger house than this one, but

the folks got old and didn’t want to

bother with strangers any more. No, I

don’t think the house will be opened

again—not right away. We don’t cater

to boarders for the summer much out

here. They are too fussy and too much

trouble. There was a man out here

yesterday who said he was an artist from

New York or somewhere. But I had to

send him along. I eater to traveling

salesmen who stay the night and go on

about their business, and are not around

underfoot.” The traveling salesmen are

mostly from St. John and St. Andrews.

The folk of Grand Manan do not care

to do much trading with the Yankees,

except when the girls take Saturday

afternoon and run across to Eastport

for millinery and ribbons.

A few years ago several ambitious gentlemen undertook to exploit Grand Manan land and to attract strangers to the island for the purpose of helping the transportation company and other allied interests. But the islanders generally cid not take kindly to the proposed in- vasion by city folk. In some instances they refused to sell land for cottage sites, and in most cases refused to sell their labor.

First and forever they are fishermen. Their fathers were fishermen. The sting of the salt spray on their cheeks, the cluek of the bow pulley when the loaded trawl comes sagging from the creaming waves, the surging rush up the seas tow- ard home and the long fish-wharves, the flapping fall of the cod and hake and haddock as they are pitchforked, “ kint’] after kint’l,” into the bins—the life of the men of Grand Manan is this—of and for the sea!

They are deft workers when the fare has been landed. Three make a team. The first slits the fish and slices off the head; the youngster of the gang finds the liver and the sound and discards the rest of the “works”: the last man splits the fish into the familiar jib-shape and slices out the back fin with one swift movement.

The last pinky of the coast is a part of the Manan fleet. She rolled in past the clanging bell-buoy just ahead of our little packet. A half-gale from the south- west drove her with more speed than our engine afforded us. But that was her lucky day, with wind and tide favoring. All the other men in the fleet have sloops, and each craft has “a kicker,” and the fishing-grounds are just fifty minutes’ run from Flage’s Cove. If the wind is not fair, the “kicker” pops the sloop to the grounds, straight into the eye of the breeze, Hand-lines, and trawls for cod, and nets for herring in their sea- son—the Manan fisherman has all the gear and is off-coast in all weathers, for his craft is sturdy and his heart is stout.

The breakwater—a tongue of wooden bulkhead—shielded our landing, after the sea had tossed us in from the open. A venerable man whose beard snapped in the wind, and whose eane and linen col- lar told that he had left fishing to the boys, took our line. They sniff strangers and the business of strangers with prompt aceuracy on Manan.

“Tf anybody ever comes out here to write anything about our island,” he re- marked, “I hope he won’t make up any stories about such things as ‘death- eakes’ and such foolishness. There was a woman who wrote a story about some- thing that she called a death-eake, and made it out that Grand Manan folk cook up death-eakes the same as folk on the main make wedding-eakes. Don’t know where she got that idea—but she had to take it back. Made her eat her own eake, as you might say. Now that

I’m off the boat and have time to myself, [ve thought of buying a camera and traveling up to the city and snapping town folk right and left. If any of the city freaks said anything to me Id tell ‘em I was looking for picturesqueness and loeal color. Then, I suppose, they wonld have me arrested. We don’t have policemen out here,” he added, with a sigh.

The coast foik in general are more sus- ceptible to religious enthusiasms than people in the intertor. Perhaps the per- petual presence of the vast and melan- choly ocean, tossing them on its breast, rolling its billows to their doors, in- clines their winds to sober thoughts. But the men and women of Grand Manan have never been carried into extravagance of religious emotion as have some of their neighbors. They are not ithe sort that would have joined that pilgrimage of Jonesport fanatics to the Holy Land—that ill-starred expedition which sold all possessions in Maine, and journeyed and starved and prayed, and begged its way back home. The Holy-

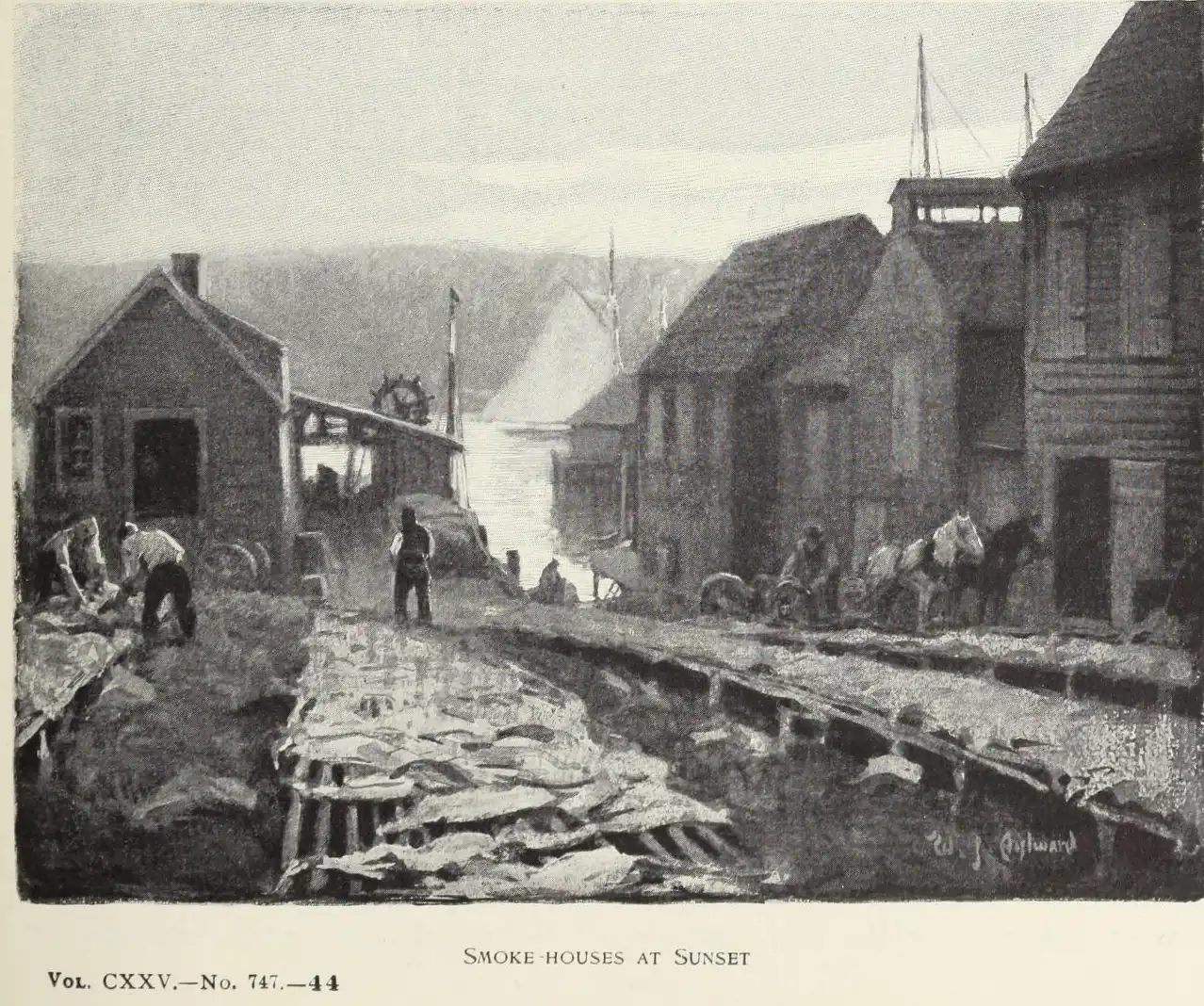

SMOKE HOUSES AT SUNSET

SMOKE HOUSES AT SUNSET

Vor. CKXV.—No, 747.44 352

Ghosters of Shiloh in Maine won plenty of coast converts for their great temple in the sand-hills of Durham, but there were no disciples garnered in Grand Manan. Yet occasionally the island ex- periences such a revival in religion that

JHE PEDDLER ON HIS DAILY ROUND

danees are tabooed and amusements frowned upon.

One touch of pieturesqueness Grand Manan has each summer. The Indians of the Passamaquoddy tribe — certain more adventurous spirits of Pleasant Point who disdain basket-work and the enervating job of selling curios at Maine summer resorts—paddle their canoes

HARPER'S MONTHLY MAGAZINE

across the fifteen miles of sea, coming: from the main, and camp at the foot of the great cliffs during the warm months. They shoot porpoises for the skins and the oil. The skins make material for belts and purses. A few years ago cer- tain erafty redskins of the tribe started a thriving in- dustry on Manan by manu- facturing seals’ noses in order to secure the liberal bounty which the State of Maine was allowing at that time. When Massachusetts offered greater inducements in the way of bounties on seals, the Indians went to that coast and earned several thousands of dollars, hay- ing become very expert in making a seal’s face out of hide and wood and _ bone. They are now serving a term in the penitentiary, having found more acute observers on their island in Massachu- setts Bay than on the wind- swept north frontage of Manan.

At the mouth of the Ken- nebee every strong souther- ly wind casts lumps of can- nel-coal up on the beach— and just where that coal eomes from nobody knows for sure, though divers have explored and engineers have probed the sand. On Grand Manan the southerlies turn up different sort of spoil. A long stretch of sandy beach often disgorges bottles of contraband whiskey. Of old a smuggler went ashore, and the eargo of that rep- rehensible craft was whiskey packed in crockery crates—a layer of crockery concealing the nefarious goods. Some of those erates were rolled and tossed and rolled again, and the sand was packed over them. The British steamer Hestia went ashore on Old Proprietor Ledge near Grand Manan—and this steamer proved a total loss, and her cargo was of an equally nefarious sort. The broad breast

of the ocean was dotted with floating cases. An unwise Fate seems to have-resolved to provide regularly and liberally for the hardy fishermen of Manan, without regard to their temperate tastes; and fishermen who go rocking past Old Proprietor Ledge snap small coins over into the sea—a modest tip to remind kind Fate that small favors are always thankfully received.There has lately been another wreck in a harbor of Grand Manan. This time the cargo performed a most peculiar antic. A schooner with thirteen hundred bags of salt came sailing from Boston town, and sprang aleak on the way.

THE MANAN FISHERMAN IS OFF-COAST IN ALL WEATHERS

The captain was an indolent man, and he loathed the spectacle of two men straining all day at the pumps; therefore he allowed his schooner to "ground out" at the side of a wharf so that his sailors would not be obliged to pump. When the craft grounded, she "hogged " in the middle because she was old and rotten, ard her butts were started. She filled promptly on the next tide, and all the salt melted and ran away into the sea, and to-day only the empty sacks are in her hold. She has been sold as she lies for four hundred and eighty dollars, and the disgusted captain has abandoned the sea.

There's the old, old story so infrequently told that it is remembered and related only by the oldest men of the island: Two sisters who were to be brides on the same day, as they had been chums together at school and inseparable from childhcod, went across to the main on their uncle's packet to buy their wedding finery. On the return they held their new hats on their laps, so that no harm could eome to the delicate fabrics —for each was the finest hat a Manan bride had ever worn. One item-of cargo was a hogshead of molasses, and _ this was trigged on deck.

When the little packet neared: harbor the two young suitors of the girl gave over their task in the fish-house and walked to the end of the wharf to meet their brides - to - be. Snap of the sail, and she came about to make her reach for the last leg of the journey! That wicked tide-rip which streams im

tossing, swirling, yeasty current from every contorted headland on the island eaught the craft and buffeted her with such a jar that the hogshead broke from its fastenings, was tripped from its trig, and rushed across the deck. The wave and the impact of the weight against the rail overturned her instantly. The wind scaled those new hats in ever the waves to the spiles INTERIOR OF A SALT-HOUSE

of the dock, and the poor, bedraggled objects were rescued with tears and laments and borne by the women to the home of anguish; the sisters were never seen again. Some of the ancient men eall the place "Millinery Rip."

Once a fisherman who was skirting the cliffs of the north shore in his sloop glaneed lazily up at the broken surface and suddenly felt his ennui depart. More than a seore of brown, bald heads from which pigtails depended were bunched at the dark opening of a cave. Many faces peered down at him with slanting eyes. The group was as silent as a convocation of ghosts. They were Chinamen, their hands folded in their broad sleeves, their countenances npassive, waiting with stolidity the motions of the men who had agreed to smuggle them into the States, and who were now trying to elude the customs officers and take up again the cargo which they had temporarily jettisoned on the bleak shore of Grand Manan. The fisherman minded his own business—a trait of the island— and the next day the temporary cliffdwellers were gone.

There was a trader of Grand Manan who decided that if he could own and captain his own packet and sail to market, and dicker at headquarters for his goods each trip, he would clear a sum worth the extra effort. So he bought his sehooner and hired a "nurse" for his first voyage to Boston. A "nurse," in coast lingo, be it understood, is a skip per who knows all about eraft and goes along as pilot and instructor. So, after he had cleared land nicely, the “nurse” gave the owner his first lesson in steering, told him to head so and so, to keep the sails drawing, and then went below to play “pitch pede” with the foremast hand—for the wind was steady and all was taut. The new owner obeyed instructions as he remembered them. He kept the sails drawing, and had no eyes for anything else. After a time he noticed that the schooner seemed to be making better time of it than she had when he had been slicing the breeze on a port tack. The wind boomed in her sails and spilled with little whistles; she rode on an even. keel, and the waters roared under her counter.

The game of cards was close and interesting, and therefore the “nurse” was as intent on his own affairs below as the trader was above. When at last the real skipper abandoned cards and came on deck he yelped his astonishment:

“We've been making great time, Cap,” stated the proud owner at the wheel. “I have kept still so as to surprise you. Tm making the best of this fair wind.”

“Fair wind!” squealed the “nurse.” “You have let her ease off! And you have been to work and sailed clear around Grand Manan back to where you started from this morning!”

And that was a sail of forty miles and more, up one side and down the other.

The owner peered under the bellying sail and saw his store and his house. The rays of the setting sun illumined them, as the rays of the rising sun had lighted the scene when he departed that day.

“Anchor her,” he said, giving over the wheel. And he hired the “nurse” for a captain and took his canvas valise and was rowed to shore in the dingy. He earned the reputation of being the only man who ever lived-on Grand Manan and lacked congenital instinct in the sailing of a boat.

There are only two other men on the island who have been compelled to en- dure any greater raillery. Off to the southward one day they picked up a huge lump of something which was oily to the touch, which had queer mottlings in tt, and greenish streaks. They had read some- thing somewhere about ambergris, and decided that they would never be obliged to pull trawls any more. The stuff was soap-grease which had escaped from a Lubee factory. And the men who found it are known as “Ambergris One” and “Ambergris Two.”

The story of Club-foot John is one to be told when the winter fires are aglow and the .snow is tossed in giant handfuls against the pane. Then, above the clang of the bell at the harbor entrance, there is a note which does not seem to be from the throat of the raucous wind. There is imagination among the silent folk of Grand Manan.

“Grands’r mumbies: ‘Miles of chain

Are out to-night from the Stormy Jane.

Brig she was, and as able a thing

As e’er tuned shrouds for the winds to sing.

But the ablest is under the Devil’s thumb

When the skipper takes sights through a kag of rum.

With a sou’east wind she thrashed her way

Up seas hot foot for Fundy Bay.

And the mate he knowed, and the crew they knowed,

She was lugging too much of a canvas load.

But still he told ‘em to crack her on—

Her drunken skipper, old Club-feet John.

They smelt the land and they begged, did they,

He’d anchor in soundings till break of day.

But a kag of rum walked that quarter-deck,

And a kag of rum don’t fear no wreck.

So down she went with every man,

Battered to slivers on Grand Manan.

A dozen lives on his black old soul,

And widders and orphans and bells to toll.

You'll hear him plain when a storm is on,

Roaring and working, old Club-foot John,

Stumping around his windlass there

Where the snow whirls thick in the off-shore air,

Clanking an endless anchor chain

Into the peak of the Stormy Jane.

That’s a duty left to Club-foot John,

Though he is long since dead and gone:

He is sent to tell us as best he can

There’s a duty due to our fellow-man.

Better be kind and better be square

And remember that rum is the Devil’s snare

Set for the man who forgets that he

Needs all his wits when he fights the sea,.’”

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1930, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse