Letters from Italy/Chapter 18

Chapter XVIII

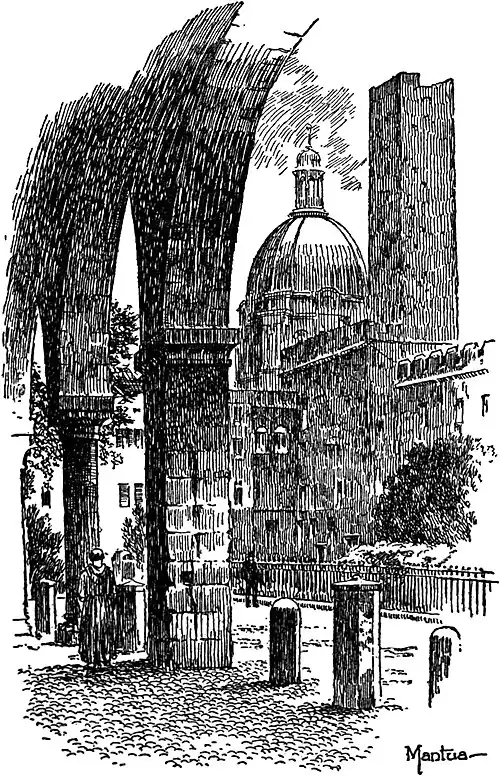

VERONA

Permit me now to abuse roundly the Italian land; it is too hot and too dear there, there are many rascals and vermin, frightful noise, Baroque itself, cabdriver bandits, malaria, earthquakes and yet more dreadful ills; and I betray all this out of revenge. Wretched Mantua, birthplace of Virgil and grave of Mantegna; miserable nest, to which I made my way with the object of examining the frescoes of the great, severe, beloved Mantegna. What was there humane and Christian in refusing my entry into the longed-for Camera degli Sposi, simply because there was some sort (I know not really what) of popular and patriotic holiday? Thick-headed custodian, who resisted the alluring rustle of my banknotes! Callous director, who shrugged your shoulders with an expression of infinite compassion and did not give way even to my threats! Dull, petty town Mantua, where three boys rushed along with a banner, enlivening the most repulsive streets in the world. And thou, Italian land, which on my short pilgrimage presented me with no less than six popular holidays, so as to drive me from the gates of the Ravenna monuments, the doors of the Umbrian school at Perugia, and all the subterranean charms of Naples I say, what an amount of mischief: and Mantua exhausted my patience. Never let a foreign foot remain in Mantua, and take heed that there are the worst beds, lack of decent food, and disagreeable people.

Having wreaked my vengeance, I will once more bow the knee before the most estimable church of St. Zeno at Verona. The chief pride of Verona is certainly Paolo Veronese, the Roman amphitheatre, Morone, the Scaligers, and sausages; for me Verona is only St. Zeno, the little Lombard brother of Norman Monreale, a homely little older and poorer brother, which has not attained to a golden head of mosaic nor a dazzling cloister, nor the wonderful abundance of gold and displayed ornaments, but only areas simple and meditative, of serious, generous interior, and especially doors; gigantic doors, covered with little brass pictures set in the portals with little stone figures. These they say were constructed by a certain Nicholas and Wiligelmus, and this brass work is reputed of German origin; but they are beautiful or rather impressive. You smile at them, and are touched by the attempts of a naïve hand to relate, to narrate the Bible, to surmount terrible difficulties, e.g., for Christ’s sake to depict Christ, Who is to wash the feet of the Twelve Apostles sitting en face: there is simply nothing else to do but to represent Christ the Lord turning His back. On every  little picture you feel the labour under stress of thought, how to execute it, how to express it, how to arrange it and set it all together; in Tintoretto, in Titian, in whatever brilliant master, you never feel so much spiritual travail, so much strain of thought, as in these really naïve reliefs. But there is nothing valid: where the spirit is immanent there it will be found; and the doors at St. Zeno are the most beautiful Bible that I have ever read in my life.

little picture you feel the labour under stress of thought, how to execute it, how to express it, how to arrange it and set it all together; in Tintoretto, in Titian, in whatever brilliant master, you never feel so much spiritual travail, so much strain of thought, as in these really naïve reliefs. But there is nothing valid: where the spirit is immanent there it will be found; and the doors at St. Zeno are the most beautiful Bible that I have ever read in my life.

And then everywhere, where there is a little space, on the bases and capitals of columns, among arches, wherever possible, the Romanesque artist has chiselled and hewn out animals: dogs, bears, and deer, hares and frogs, horses, sheep and birds. They are entirely different animals from those on the antique reliefs; there you have a Calydon boar or dolphin of Venus or something else entirely from mythology, or naturalistic portraits of animals; but there is the same nature, the same preference for field and forest animals as they left the hand of the Lord; the relationship of man to the animals is more intimate, more sincere, and let us say more humane than in all antiquity. Man has personally to do with animals, for good and evil. Adam driven out of Paradise must dig, but—just as at St. Zeno’s—he kills and smokes little pigs, likewise treads out grapes, reaps, plucks apples, rides horseback and hunts beasts; why may not the bear and the stag glorify the Lord on the front of St. Zeno? Yes, there is another, fresher relation to the world; and believe me, never shall we understand the decline of the magnificent antique, if we do not discover the worthy, humane virtue in the simplicity of the age which surmounted the antique.