Page:The New England Magazine 1891, 5.1.djvu/2

would be allowed to wear again his favorite coat and hat.

He was a naughty boy in little ways, though full of fun and of generosity, liking to argue, and generally gaining his point in discussion with other lads, especially if it were about the subject of religion. When he had been unusually obstinate, he comforted himself by his faith that God would interpose on his behalf and make him have a good time after all, in spite of the punishments he was called upon to bear and the loneliness that crept over him. Moreover, his dreams assured him that he was a special favorite of the Almighty.

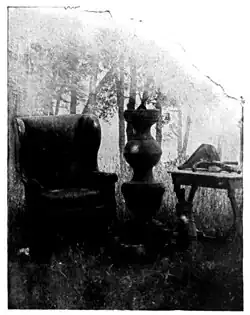

The Admiral's Chair and Other Relics.

In 1788, the boy became a midshipman in a line-of-battle ship, and in due course of time cruised in the Bay of Fundy, helping in its survey. For three years his man-of-war must have been stationed at Campobello. His crew often went ashore in summer, tending a little garden in Havre de Lutre, and carrying the dahlias, for which the island has always been famous, to the pretty girls and the Owen ladies at Welshpool, who in return in the winter went to many a dance on board his ship.

The boy grew into the middle-aged man, and when sixty-one years old, with the rank of admiral, came back to Campobello to live. Somewhere in that long time he had captured two cannon from a Spanish pirate, and carried them away to his American home. Proud as he was of them, there is now no one living to tell who bled or who swore, or whether the Spanish galleon sank or paid a ransom. He placed them high on Calder's Hill, overlooking the bay, where they bid defiance to American fishing boats—for Campobello belongs to New Brunswick. He planted the sun-dial of his vessel in the garden fronting his house, and put a section of his beloved quarter-deck in the grove close to the shore. There, pacing up and down in uniform, he lived over again the days of his attack upon the pirate ship. He went back and forth over the island, marrying and commanding the people. He kissed the girls when he married them, and took fish and game as rent from their husbands. Now and then he gave a ball; oftener he held church service in what was almost a shanty, omitting from the liturgy whatever he might chance to dislike on any special Sunday.

Lady Owen was queen as he was king, and never did a lady rule more gently over storeroom and parlor, over Sunday-school and sewing-school. The brass andirons shone like gold. The long curving mahogany sofa and the big leathern arm-chair, with sockets in its elbows for candles, still tell the primitive splendor of those days. Religion was discussed over water and whiskey, and the air, thick with murkiness from the clay-pipes, recalled the smoke of the naval battles.

Remittances did not always come promptly from England, and money was