Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3850

CHARIVARIA.

A letter received in Bâle from a responsible source states that it has been decided to kill all dogs in Germany, "with certain rare exceptions." These will, of course, include the Mad Dog of Potsdam.

⁂

Wehr und Waffen has been pointing out that human hair makes an excellent substitute for the lime-destroying material which is ordinarily used in the boilers of war-ships, and it advises patriotic Germans to pay a visit to the barber's. As a consequence of this appeal Admiral von Tirpitz, it is reported, is contemplating parting with his famous whiskers before they get singed again.

⁂

"With regard to the statement of the British Government that the German Navy neglected to rescue shipwrecked men," says a German Official Note, "the inference contained therein that rescues have been intentionally neglected can only be denied with horror." The horror is ours.

⁂

For the following Charivarium we are indebted to the Frankfurter Zeitung. It is extracted from an article complaining of the unimpressionable natures of Northern France, whose country has been devastated by the enemy:—"When our troops pass along the streets to the sound of music, which anywhere else would awaken the souls of men, there is no awakening echo; there is silence, an indescribably saddening silence, which seems to mock our most serious efforts to make friends of these people and accustom them gradually to the misunderstood benefits of German civilisation." The professional humorist can do nothing with this kind of stuff.

⁂

Annapolis, U.S.A., was startled, the other day, by what sounded like the explosion of a heavy bomb. It transpired that the German language had been dropped from the curriculum of the Naval Academy there.

⁂

It was rumoured last week that Lord Hugh Cecil, who wrote to The Times to announce that it was not his intention himself to abstain, had perished under an avalanche of whisky advertisements.

⁂

Thousands of confirmed teetotalers have announced their intention of following the King's example with regard to intoxicants.

⁂

Certain advanced opponents of strong drink are going to strange lengths, and a Mile End dairyman has got into trouble for adding water to his milk.

⁂

"I must admire England's colossal skill in the invention of lies," says Admiral von Tirpitz. This is, anyhow, praise from an expert.

⁂

The Simplified Spelling Society is reported to be interesting itself in the Przemysl and kindred difficulties. Might we draw the attention of this Society to the fact that the Turk is also unspeakable?

⁂

It has now been decided to utilise Alexandra Palace for the reception and detention of German prisoners. The Germans are gradually getting all our Palaces; Buckingham Palace, however, still holds out.

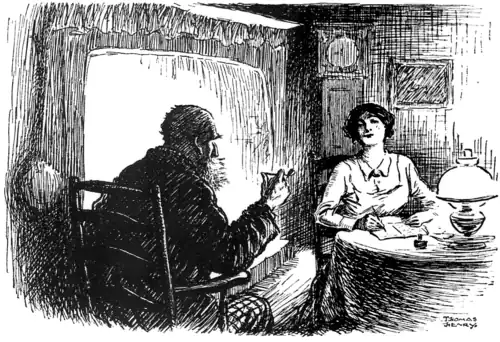

Sister (writing letter to brother at the Front). "And hae ye onything else tae say, father?"

Father. "Ay! Tell Donal' that if he comes ower yon German waiter that gaed us a bad saxpence for change when we had a bit dinner in London a while syne, tell him—tae—tak—steady aim."

At Christie's.

"The total for the day's ale was £3,855."

Evening News.

Auctions are thirsty work.

"The ideal of the prohibtotalition of the sale of alcohol seemed to him to be fraught with a great deal of difficulty."

Leamington Daily Circular.

We confess that the mere mention of it terrifies us.

"Our Future Lies on the Water. By a Prussian Officer," is the recent announcement of an English translation of a German work. We look forward to them with interest, though we doubt if the Prussian officer will be able to outdo what Wolff's Agency has accomplished on land.

From a catalogue of gramophone records:—

"'A Love Song.' (Kaiser.)"

A pleasant change from the "Hymn of Hate."

The following recently appeared in the "Orders of the Day" of the 4th Queen's at Lucknow:—

"The Bishop will preach at the Parade service. Troops will take twenty rounds of ball ammuuition."

This precaution was presumably adopted in case the Bishop should deliver a charge.

Extract from The Mark Lane Express, Agricultural Journal and Live Stock Record:—

"Cheese continues to move upwards. All sorts share in the movement, and there are some curious kinds."

There are; and apparently they all come into the category of "live stock."

A Sweeping Assertion.

"At first there seemed danger that mines with which Channel plentifully strewn might prove greater obstacle than forts, but mine news-papers have hitherto been able clear course efficiently."—Pioneer.

In this admirable enterprise The Pioneer naturally leads the way.

"A resolution was adopted which instructed Secretary Rigg to write to the department of militia asking for:—(a) The names of the shoemakers who were catering for the feeding of the troops; (b) the names of the cooks and caterers supplying the boots and shoes; (c) the names of the lawyers who had been successful in the contract for the tailoring supplies."

Winnipeg Free Press.

We can understand that the first two items should have caused some dissatisfaction, but surely the lawyers ought to have been competent to look after the suits.

From a Sale Catalogue:—

"Plaid Silks in all the latest Clans Good Quality."

The older clans are, of course, quite démodés.

THE ERRORS OF OMNISCIENCE.

[Herr Ballin, returning from the Front, where he had an audience of the Kaiser, has given to an American interviewer on account of his Imperial Master's views about the War. Wilhelm II is represented to have said: "I never desired this war. Every act of mine in the twenty-six years of my government proves that I did not want to bring about this or any other war." He ascribed its origin to the diplomacy of Sir Edward Grey. He was certain of victory, but offered no pronouncement as to the date of its consummation.]

THE DRILL BOOK.

"You seem," said Francesca, "to be profoundly interested in that little red book."

"Hush!" I said. "Don't speak to me, or you'll drive it all out of my head. It wasn't very securely lodged, anyhow, and now it's gone. I shall have to begin all over again."

"What in the world is this man talking about?"

"Francesca, I will tell you. This man is talking about The New Company Drill at a Glance."

"Oh, but you've done much more than glance at it. I've been watching you for half an hour, and you've pored over it, and groaned over it, and turned it sideways and upside-downways, and yet you don't seem to be happy."

"I will not," I said, "disguise from you that I am far from happy. This book contains numerous diagrams beautifully printed in red and black. Diagrams always make me feel that they are printed the wrong way round, and that I should understand them perfectly if I could only stand on my head or turn myself temporarily inside out. I can't do that, so I try to turn the diagram inside out, or get it to stand on its head. I'm like that with maps, too—but it's not a bit of good. I only get more and more confused. Napoleon wasn't afflicted like that. He just sat down in a barn or somewhere and studied his maps, and then went and won a battle."

"Why drag in Napoleon?" said Francesca. "You're a Platoon Commander of Volunteers, and you're knocked off your perch by a diagram in a little red drill-book. Well, throw it away. Trample on it. Put it in a drawer and forget it."

"How can I forget what I've never known? No, I must go on trying to learn it. I must tread my weary path alone. Francesca, how would you make a line form line of platoons in fours facing in the same direction?"

"I should just ask them to do it, you know. I should appeal to their better feelings and say, 'Now, men, you've got to form a what's his name in fours. I'm sure you won't leave me in the lurch, so get to work and form it; and, whatever you do, mind you face in the same direction.' That would fetch them, I'm sure."

"It would," I said; "and it would also fetch the inspecting officer and all the other big bugs who might be present."

"Well," she said, "how would you and your little red book do it, then?"

"I should inflate my chest and shout out 'Advance in Fours from the right of Platoons. Form Fours———' and there's a lot more, but I've dropped my glasses and can't read it."

"Ha ha!" laughed Francesca. "An officer in eyeglasses! Extract from Sir John French's despatch: 'At this point a Commander of Volunteers began to order his men to form fours in platoons facing in the same direction, but, having dropped his glasses, he was unable to read his drill-book and was immediately afterwards taken prisoner with his men. This regrettable incident deprives the army of a very gallant officer.'"

"Laugh away," I said bitterly; "pour cold water on my enthusiasm. If you can't think of anything better to do I suggest your leaving me alone with my drill-book, for I'm determined to master it, diagrams and all."

"That," she said, "is the spirit I like. A father of a family, fairly well on in years, is left alone with a drill-book, and sets his teeth and gets the better of it. But tell me, do they really have to do that sort of thing in the trenches?"

"Oh, yes," I said, "they do it constantly. No day can be called complete unless they form line of platoons in fours facing in the same direction."

"I haven't noticed anything about it in the soldiers' letters in the papers. They generally say the Jack Johnsons covered them with earth, but that they fixed bayonets, rushed the last twenty-five yards and got back a bit of their own, and what brave men their officers are. If ever you have to fight I should like your men to say that of you."

"If you really want that," I said, "you must let me mug up this infernal drill-book. If I don't know something about it I shall never be able to face the inspection next Sunday, let alone rushing the last twenty-five yards into the German trenches, which I shall certainly endeavour to do if I ever get the chance."

"Well, I'll give you a quarter-of-an-hour all to yourself, and then I'll come back and hear you say your drill."

"Splendid! That's the way to help a Volunteer."

"Yes, I'll be an Army Corps or a Division or a Brigade, and you shall order me about to your heart's content."

"Good; but if you're not quick about forming forward a column of fours into column of platoons there'll be trouble."

"I'll form forward," she said, "or perish in the attempt."

R.C.L.

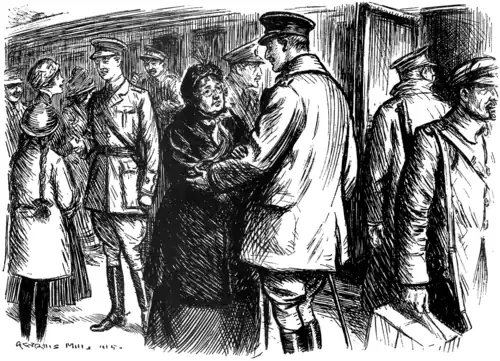

DELIVERING THE GOODS.

Mrs. Brown (to Mrs. Jones, who has also been to see a son off in troopship). "Well, I'm sure they'll be starting soon, because both funnels are smoking; and, you see, my dear, they couldn't want both funnels just for lunch."

THE REPRIEVE.

Tr-r-r-r-r-r-ing!

It was the alarum clock in the far corner.

Some people place alarum clocks close by the side of their beds. This is a foolish and expensive plan, since by merely reaching forth an arm it is possible, with practice, to hurl the diabolical instrument through the window in one's sleep, and then to subside again beneath the blankets. On the other hand, if you really have to get out of bed, you really have to wake up, unless of course you are a somnambulist, in which case you ought to sleep in a cage.

As I dragged myself slowly from my dreams I realised (1) that I was a Special Constable due for duty from two till six A.M.; (2) that I had ordered Jessica, our general, to set the clock for 1.15; (3) that it was raining; (4) that I had a slight cold and a touch of dyspepsia; (5) that as the gas-stove in the back kitchen was out of action I could not brew myself a cup of tea. I cursed the Special Constabulary and all their works of darkness, dressed very quickly and crept downstairs. I then cut myself some bread and cheese, which was all I could find in the pantry.

As I sat eating this in the kitchen I felt my spirits sink lower and lower. I thought bitterly of the Kaiser, the man responsible for all my woes. What was it to him that I was at present laying the seeds of indigestion beside an extinct kitchen fire, and should shortly be wandering for interminable hours through interminable lanes with a companion as dejected as myself, our only solace a couple of police whistles, from which it was impossible to extract the faintest resemblance to a tune? Nothing. Perhaps he had not even been informed that I was a Special Constable at all. I thought despairingly of the price of coal, and wondered how long it would be before I was reduced to felling our only apple-tree for fuel, and whether I should be able to do it with a table-knife or should be compelled to purchase an axe; and, if so, what was the price of axes. I thought regretfully of my golf handicap of eighteen, the fruit of years of untiring devotion to the game. By the time the war was over (if it ever was over) I should probably have sunk to an indifferent twenty, and my niblick and I would meet almost as strangers. Why, I asked myself, did Heaven permit these things?

At length, my bread and cheese disposed of for the time being, I rose and prepared to face the elements. As I did so my eye fell on the clock on the mantelpiece. It showed the hour as twenty minutes past six. Jessica had placed the alarum in my room, but had inadvertently set it as if for her own usual hour of rising.

In the crises of life a man will often mechanically seek relief from the stress of overpowering emotion in the performance of some apparently trivial_act. I stooped and unlaced my boots. Then I crept upstairs again.

Manchester and Salford Councils decided yesterday to advance the price of gas 6d. per cubic foot, largely owing to the advance in coal prices."—Daily Mirror.

With gas advanced by £25 per 1,000 ft., Manchester and Salford householders may be advised to try electricity."

"Things our men at the Front will appreciate.

———'s Backache Pellets."Advt. in "Birmingham Gazette."

We do not like the innuendo. It is unjust, though, no doubt, undesigned.

"I venture to say that if I stopped you in the street, or even in the next street, and asked you what the calibre is of the guns latterly employed in puncturing the Dardanelles, your answer would be an unhesitating 'No.'"

And a very good answer, too, for this kind of bore.

"Wanted, Lads for Bottling."

Advt. in "Lancashire Daily Post."

This advertisement is obviously belated. Nobody asks nowadays for "a bottle of the boy."

A ZEPPELIN POLICY.

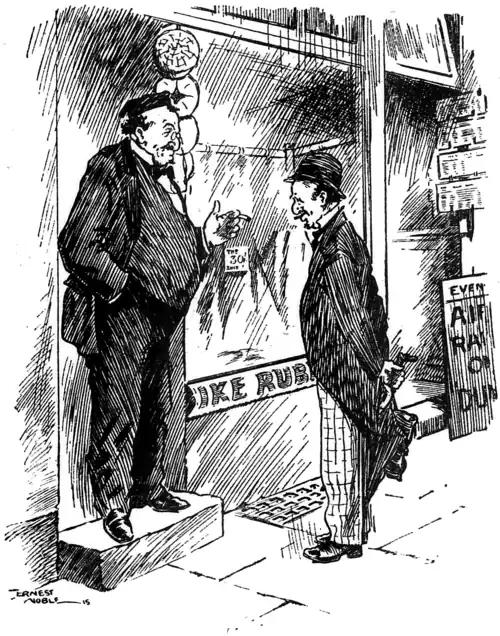

"Goin' to 'ave yer annual fire, Ike?"

"No, my poy—not in war-time. I haf painted a red cross on the roof, and I vos trust in Providence."

NIGHT OPERATIONS.

It happened in the Park. As we didn't really need the whole Park and didn't want to be a nuisance to all the couples who resort there for quiet conversation, we staked out a pitch. The pitch was bounded by two parallel roads, and the roads were in play. Four scouts played against B Company. The commander of B Company won the toss and decided to defend the south end. The object of the scouts, who were loaded with rifles, was to pass through the company's lines without capture. The rifles, which are not well adapted for other things, were carried for the purpose of recognition only. I was cast for a scout, and was abetted, if not aided, by Holroyd, Henderson and Higgs.

They turned out to be unimaginative pig-headed people, and on one excuse or another they refused in toto to adopt any of my suggestions. Holroyd, who is a long thin parsimonious person, declined on the ground of expense to hire either a property tree or a piano organ. Concealed in either of these I am sure that he would have had an excellent chance of getting through. Henderson, who is a young and somewhat effeminate-looking individual, contemptuously rejected the idea that he should go as a nursemaid, with a perambulator in which he could conceal his rifle. He seemed to think that it would be unmanly and unsoldierly. His only idea was a false beard and a wig. I pointed out that however desirable it might be to alter his appearance in daytime it was not so urgent in the dark, and that it would be of small strategic benefit as he was personally known to only about five per cent. of B Company. In the end he got quite stuffy about it and we nearly had words.

Higgs's only excuse for not covering himself with grass sods and crawling along on his stomach was the damp and muddy nature of the soil. Of course when I found out that he was going to let a little personal discomfort stand in the way of success I gave up trying to help him.

My own scheme for getting through, though entailing a certain amount of cost, was simple and effective. I decided to hire an ordinary taxi and drive down the left-hand road as fast as the Park regulations would permit. When the others heard about it they all wanted to come with me, but this would have increased the cost, and we should have looked rather small if by any chance the taxi had been stopped and we had all been captured together. I made Higgs a sporting offer to allow him to hang on behind if he would pay part of the fare, but we failed to strike a bargain.

Holroyd consented to adopt my suggestion that he should conceal his rifle down the leg of one of his trousers. We had some difficulty in getting it there, and then he found that it restricted his movements. He also complained of discomfort. We wasted quite a lot of time trying to get it out again. We couldn't think of the proper technical way to go to work, and there was no help to be got from our military books. I looked in both the Musketry Regulations and Infantry Training, but, strangely enough, neither of them deals with a simple point like that. I know that on active service a soldier, owing to the use of putties, is not likely often to get his rifle into this position, but still, as in Holroyd's case, it might happen. By the rather crude method of all pulling at once, we eventually managed to separate his leg, rifle and trouser. It was largely due to Holroyd's own impatience that several pieces of his flesh and trousering adhered to the nobbly bits of the rifle. After that they all declined to listen to any more suggestions.

I was still rather troubled about my own rifle, as I felt that it might be detected if undisguised, in spite of the taxi. I couldn't reasonably expect even B Company to mistake it for an umbrella, swagger cane, policeman's truncheon or lady's reticule. I thought of concealing it in some musical instrument, but couldn't hit on anything suitable, though I went through all the instruments I could think of from an ocarina to a big drum. In the end I decided to adapt my brother's violoncello case. I'm not a very good amateur carpenter, so it wasn't a very neat job, though it served.

As I anticipated, I was the only scout to get through undetected. The other three were all captured and brought in, in addition to the thirty-three civilians, six special constables, five real soldiers complete with lady friends, four territorials, two park keepers and one park chair captured in error. Several civilians, most of the special constables and all the real soldiers were annoyed at being interfered with, and I understand that there are two actions for assault and battery and three for false imprisonment pending.

Higgs, it appeared, did, after all, adopt my stalking suggestion, though without its best feature—the divot disguise. By crawling on his hands and knees he had almost succeeded in getting through the lines when a clumsy Section-Commander trod on the nape of his neck. Owing to the mud in which he was encased he might still have gone unremarked if only he hadn't groaned.

Henderson's notion of climbing up a tree wasn't a bad one, though I can't quite see how it helped his progress to any extent. His detection was due to his accidentally dropping his rifle on the head of the Commander of No. 1 Platoon.

Holroyd, one of the park-keepers, and the chair were captured en masse. Holroyd seems to have had the idea that the chair would in some way assist him in his enterprise, and the parkkeeper was disputing his right to use it without payment when they were surrounded.

I thought that the Company-Commander was somewhat sparing with his congratulations to me, but no doubt he was frightfully chagrined at the success of my simple ruse.

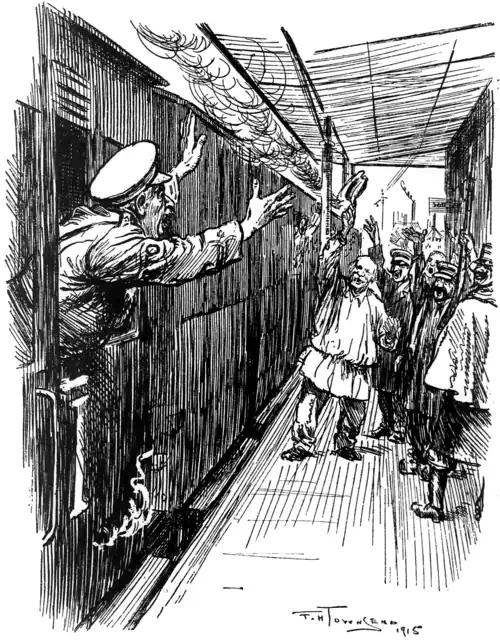

SOMEWHERE IN FRANCE.

Railway Transport Officer (being carried off from his station in a British Supply Train). "Stop the train! Stop the train!!"

Chorus of French Railway Officials (mistaking his gestures). "Vive l'Angleterre! Vive la France!"

RENAMING A ROSE.

I forget when we—that is, our local choral society—first began to practise Acis and Galatea. I know it was long before the start of Lent. Anyway, a few weeks ago we decided that we knew enough about it to risk our annual public performance, and the posters were about to be issued. Then one evening the blow fell at a committee-meeting. We were busily discussing the all-important point of the colour of the paper for the programmes when Appleby (our only tenor who can take a top G without causing grievous bodily harm to himself and those in his immediate proximity) rushed into the room in a state of uncontrolled emotion. It had got about, he told us, that the composer was a German, and the tickets in consequence were going as flat as our choir when they sing an unaccompanied glee. "Old Mr. Chivers," said Appleby, "has been tackling me about it. He says it's a shame to perform the work of a German composer when now is the time to support our home products."

Then a long altercation ensued as to whether Handel was or was not to be considered a German.

"But surely he became naturalised," said Miss Mallows, appealing to Mr. Bowles, our conductor, "after spending all those years in England, paying English rates and English taxes and———"

"And writing Italian operas," added Appleby.

"I really don't know for certain," said our harassed conductor, who always received ten per cent. of the gate-money as remuneration for his services. "I—I think so."

"But he ought to know for certain," whispered Miss Parmenter to me. "It's his business. If he doesn't know, what's he doing with all those letters after his name, F.R.C.O., L.R.A.M., Mus. Bac., F.T.C.L., A.G.S.M.?"

"At all events," announced Miss Mallows solemnly, "I feel it my duty as a patriot to decline, under these doubtful circumstances, to assist at the concert."

Miss Mallows' powers of musical assistance are, I am afraid, long past their zenith, but her ability to dispose of tickets still remains undiminished. Hence her decision came rather in the nature of a Zeppelin.

"Handel must be interned," I said, "and we must revive an old favourite. As Mr. Chivers hinted, it's a fitting opportunity to perform a native work."

Mr. Bowles, who had just completed an oratorio on the subject of Og, King of Bashan, enthusiastically agreed.

"But it must be something we know pretty well," remarked Miss Parmenter.

"What about The May Queen? We know that backwards."

"The point is," I observed, "do we know it forwards?"

"Then there's The Lost Chord," suggested Miss Mallows quite seriously.

"And Eric; or, Little by Little," put in the irrepressible Appleby.

"The Lost Chord," I kindly explained, "is not, strictly speaking, a cantata. It is more usually performed as a cornet solo. Occasionally one hears of its being given as a song with harmonium accompaniment."

"I didn't mean The Lost Chord," Miss Mallows corrected. "I meant The Ancient Mariner."

"Why not try high and do The Dream of Gerontius?" said Appleby. "There's a fine chorus of Demons in it which would bring the house down."

"Don't you think," asked Miss Parmenter, "that we had better do something to keep it up? Besides, two rehearsals are not sufficient. We should have to call it The Nightmare of———"

"Stay!" cried our conductor. "Why not change the title of Acis and Galatea and the name of its composer?"

"Splendid!" I said. "But won't the words give us away?"

"Not they!" exclaimed Appleby. "Everyone always says that the words we sing are absolutely unintelligible."

*****

It only remains to add that we drew a bumper house for our "performance in concert form of Dido and Æneas, the operatic masterpiece of England's greatest musical genius, Henry Purcell."

THE WATCH DOGS.

XVI.

Dear Charles,—We are now holding our own little bit against enormous odds, the latter being partly Germans but mostly rain. Even so we find the trenches a pleasant relief, since our allowance of discomfort is now defined. Up till now they couldn't make up their minds as to what exactly we were. Sometimes they thought we were fully qualified experts, fit for all the deeds, dangerous and dirty, which soldiers have to do, while at other times they a regarded us as amateurs, requiring instruction. Between the some times and the "other" times there was little margin for rest and recreation.

Now it's over, I may tell you that the instruction is even worse than the thing itself. We didn't so much mind digging practice trenches as filling them in again. We had done such as lot of this that we had come to the dismal conclusion that herein was the ultimate destiny for all of us, lawyers, landed proprietors, engineers and undergraduates alike. We saw ourselves left here, long after the War was over, filling in trenches in Flanders when we should be dining honourably in London. Moreover we foresaw that our ultimate convenience would be sacrificed, in an expansive moment, to the cause of universal peace, and, when we had finished the English, Belgian, French, Russian, Japanese, Servian, Montenegrin, Roumanian, and Italian lines, "My dear Kaiser," the authorities would write, "bygones being bygones, please remember you have only to drop us a postcard and we will send you a thousand or two industrious, if incompetent, spademen to fill in your trenches for you. You might pass this on to your Austrian, Hungarian and Turkish friends. And believe us, very sincerely yours..."

As it is, I reckon I'm now off trench-filling for ever. I would far sooner be shot for insubordination than stir a limb to destroy this "little grey home in the West" I have dug out for myself and Captain Johnson. Take my word, there comes a time in a man's life when he attaches far more importance to a judicious admixture of matchwood, sandbags, straw and mud of his own contriving than to the most luxurious combination of chintz and Chippendale designed and executed by paid hands.

We marched up here, three days back, in a mood of ferocious silence, my captain providing the sole domestic touch by leaving his washing at the last complete building on our route. The people we relieved (in more senses than one) were delighted to see us, but, recollecting suddenly that they had important business elsewhere, vanished by the back door as soon as ever our faces were turned to the front. The Germans, however, were more courteous: realizing the arrival of slightly bored strangers, they at once treated us to a pyrotechnic display of commendable thoroughness, combining entertainment with instruction, expensive illumination with unquestionable realism. Since then the spasmodic crackle of rifles has not ceased; snipers snipe industriously, and bombs and rifle grenades arrive and depart every now and then by way of comic relief. We enjoy the privilege of watching artillery duels from the ten-pound seats in the middle. Captain Johnson has a personal grievance, since the objective of the enemy guns is the last complete building above mentioned. "The low hounds," he murmurs, standing on our front door step and shaking his fist at the horizon. "Not content with making a target of my personal existence, they must needs go shelling my pants with their shrapnel and high explosives." And we continue our present lives, spending to-day in getting rid of yesterday's rain and looking forward to to-morrow's.

I write, after a sort of high-tea-dinner-lunch in my dug-out (where no parcel containing victuals or drink ever comes amiss), and from both sides of me penetrates the singularly trifling conversation of the men. They are enjoying a period of rest, and the general state of their spirits is not so much boisterous joy as comatose content. I have often wondered exactly what motive—duty, enterprise, sport or adventure—brought them all together here; in one case I have been enlightened only this morning. The sanitary man, always ready for conversation in the intervals of his ambitious work, informed me as to his own case. It appears that at the end of last July he was affected with general nervous debility. His doctor recommended a fortnight at the seaside. The sanitary man (then a clerk) protested poverty; his wife insisted on the change of air, and the combined ingenuity of the three suggested enlistment in the local Territorial battalion, with an eye solely to its yearly encampment. And here she is in muddy France, executing his (shall I say disquieting?) labours amidst relentless shot and shell, whose object is to kill rather than cure. Meanwhile rarely was a more rosy and less nervous warrior than our old-time invalid.

In conclusion let me tell you of the affairs of Lance-Corporal Rice. For years past he has professed Wesleyanism, and has paraded with the minority of a Sunday. I have even known him to do this, with a set expression of feature and great dignity of bearing, in a minority of one. But times change and we change with them, and, whether it was that some epoch-making event occurred to convert him or whether it was that the Church of England parade happened (for once) to be an hour later in the morning than the Wesleyan, our Lance-Corporal fell in last Sunday with the majority. His Platoon Sergeant may, for all I know, be a keen church-goer in ordinary life, but in war he is a stickler for regulations. "What are you doing here?" he asked the Lance-Corporal, and, after a long conversation, was finally convinced that his man was deliberately parading with the Church of England. "Get away with you,' said the Sergeant, not caring what the other believed or didn't believe. "If you want to change your religion, you can't just do it like that; you must go to orderly-room and do it proper."

I have stolen this item of news, by way of compensation, from our Second in Command, who, happening to call on me at my trench at 11 A.M., stole from me my biggest and best peppermint drop. Next time you write, enclose a candle, a piece of soap, a bundle of toothpicks, and a stick of nougat, a parcel which, if you had sent it me a year ago, would have proved you to be a poor farceur.

Yours, as long as I'm my own, Henry.

Fashions for Men.

The Morning Coat-Cowl.

"Somehow the old atmosphere of the 'Row' has completely gone—the 'knut' has vanished as if he had never been. The conventional silk hat and morning coat was only to be seen here and there and at rare intervals, and then on the heads only of elderly men."

The Daily Mirror.

"Sir Stanley Buckmaster, the Solicitor-General and Director of the War Press Bureau, who has gone to Scotland for salmon-fishing, landed a 10 lb. fish one day this week."

Evening News.

The Press Bureau has no objection to the publication of the above statement, but takes no responsibility for its accuracy.

"In Scandinavia, where men drink horribly owing to the damp-cold climate, the Government has introduced the Swedenborg system, which has accomplished wonders."—Mr. Austin Harrison in "The Sunday Chronicle."

Swedenborg dealt with the spirit, it is true; but not in this sense. Mr. Harrison, before he tackles this subject again, should consult the wise men of Gothenburg.

THE ARGUMENT FROM POSTERITY.

Elder Sister (firmly) to her little sister, who has been playing at soldiers and is thoroughly bored and now clamouring for her doll). "No, baby, you can't have your dollie. What are we to say to our children when they ask what we were doing in 1915?"

THE RED CROSS COW.

We are scrupulously careful in our neighbourhood to do and say nothing that can disparage the great effort being made by our rivals at Christie's in aid of the Red Cross. All the same we are privately of the opinion that we do this sort of thing better down our way. No one can claim to have actually invented our method; it just evolved itself. But it is working like a machine.

It began last October, when the Rector, who is one of our most progressive farmers, announced his intention of selling his little Jersey cow by auction in aid of the Red Cross. We had always envied him that cow; she was the daintiest little creature in the parish and said to be a fabulous milker for her size. So the bidding was pretty brisk. The Colonel got her for £27 10s.—an outside price, but she looked remarkably well in his paddock. We offered our congratulations and imagined the incident was closed. But the Colonel was never happy about it.

"I've got it into my head," he would say, "that that cow belongs by rights to the Red Cross. I don't believe that I shall be able to keep her with any satisfaction to myself."

He tried to square his conscience by sending the milk to the hospital, but it wasn't any good. So he put her up (for the benefit of the Red Cross) to public auction on the first Saturday in December, and asked all the more likely buyers to lunch on that occasion. When she got hung up for a time at £26 Dr. Sharpe "simply out of decency" sprang her to twenty-eight. It would be intolerable if the Colonel were to lose by it, he said. There was some confusion of idea there perhaps, but the principle was sound.

Somehow this little auction of the Colonel's set a precedent which we felt bound to follow later on. Of course the Doctor couldn't keep the cow. He recognised that at once, the more so as he had neither a field nor a shed to put her in. So his auction was rushed on without delay. It was the best of the series so far, being preceded by quite a big At Home, during which the cow was led round the lawn before the drawing-room windows. She cost_me £31, and I sent my cheque to the Red Cross.

It was about this stage that the Cow Committee came into existence, in response to a general demand that the thing should be put on a more definite basis. The Committee consisted simply—it will be seen that there was a perfect simplicity about the whole affair—of those who had made bids. It met at the school-house every Wednesday night to consider and draw up the Regulations; but the cow had changed hands three times before these were complete. I am requested by my colleagues to publish them here as a guide to other neighbourhoods who may wish to raise money for the War Funds. I ought to add that it need not, of course, be a cow. Any desirable object, from an umbrella to a rare postage stamp or a deer forest, will do equally well:—

(1) The cow shall be sold by public auction at intervals of not more than one calendar month.

(2) The entire proceeds on each occasion, without any reduction whatever, shall be devoted to the local Red Cross Fund.

(3) It will not be considered sporting (though this Committee has no jurisdiction in the matter) to allow the cow to go for a lower price than on the previous occasion.

(4) There shall be no limit to the number of times that any one buyer may hold the cow—so long as she is always bought at progressive prices—but she shall not be held twice in succession by any one buyer.

(5) The cow can be won outright by being held three times by the same buyer, and shall become his absolute property at the conclusion of the third term (if he is rotten sportsman enough to keep her).

(6) During the monthly tenure the milk, if any, to be the absolute property of the cow-holder. But the cow must be efficiently kept up. (Here follows the official list of daily rations prescribed).

(7) All disputes of any sort whatsoever to be settled by the instant re-sale of the cow.

(8) These conditions to hold good only for the duration of the War. The party that happens to be the holder at the moment when peace is signed to remain in possession.

We rather pride ourselves on this last clause, which ought to help to brighten things up towards the close. There is already strong rivalry, and any important advance of the Allies is sure to lead to lively markets. Prices are getting too high for me, but I mean to have one more flutter when we cross the Rhine.

Meanwhile a delightful thing has happened. The Rector (who got her back again three weeks ago) has just announced a calf. An emergency committee meeting has been called. It is not yet certain what steps will be taken, but opinion is pretty evenly divided between the Wounded Allies Committee and the Polish Relief Fund.

"How is it you're not serving, young man?"

"Early closing to-day, Sir."

"Gott strafe England."

We understand that our friends on the other side of the Tweed are greatly annoyed at the continued use of the word "England" by the Germans, and are contemplating seeking the assistance of the American Ambassador at Berlin to get the word "Britain" substituted.

"The Ward Unions.—This pack brought their season to a close on Saturday, the 3rd inst., when Mr. Maynard gave us 'one extra' meeting at Dunshaughlin, which resulted in a rattling good gallop of nearly an hour, and sent us all home in the best of humour, to hibernate until next October."—Irish Life.

More Hibernico.

"Country Holidays.—Country house, with farm adjoining, high inland situation, with sex breezes."—Advt. in "The Times."

This particular quality of breeze can sometimes be obtained without leaving home.

"The Spelling Indian Names.

A Revised Quide.The Pioneer.

If the new spelling is to be at all like this, we prefer the old.

REJECTED ADDRESSES.

ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

House of Commons, Wednesday, 14th April.—Parliament, worn out by a month's Easter holiday, resumed its sittings. Attendance in Cominons pretty full. Looked forward to hearing statement from Premier with respect to newly-appointed Committee authorised to control and speed up supply of munitions of war, and to learning something definite as to proposed treatment of drink. Harried Premier, to whom mention of "an eight hours' day" is a mockery, not in his place when Questions opened. Hurried in five minutes later. Anticipated inquiries not made. Will be submitted later, when further progress is made with both businesses.

In the meantime Wing, Member for Houghton-le-Spring, hovering aloft, a human aeroplane, dropped unexpected bomb in shape of painfully pointed query. Wanted to know whether Government are prepared to suspend sale of alcoholic liquors in refreshment rooms and bars of House, so placing Palace of Westminster on same footing as other Royal palaces?

Premier, enough on his hands without addition of this ticklish question, pointed out that the matter is one for consideration of House, not for decision of Government. Member for Houghton, still on the Wing, proposed forthwith to discuss it. Opportunity provided on formal motion to go into Committee of Supply. Bonar Law suggested that so grave a subject would be better dealt with in form of definite Resolution. Premier promising to provide facilities for dealing with one, affair stood over.

Meanwhile whole-hearted sympathy goes out Chairman of Kitchen Committee. The post, equally honourable and important, has been held by Mark Lockwood through long succession of sessions. He has devoted himself to service of his fellow-Members with self-denying energy recognised as establishing debt of profound gratitude. His record is, to certain extent, hampered by supreme achievement of the Shilling Dinner. Less observed have been his untiring efforts to keep the House cellar filled with wine and spirits of the highest quality compatible with the lowest price.

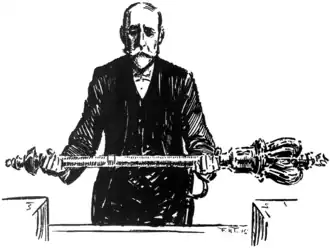

Chairman of Kitchen Committee depressed by menace to House of Commons' cellar.

(Colonel Mark Lockwood).

And now there is prospect of its being locked up for indefinite period.

As the Colonel walked about the Lobby this afternoon, the perennial carnation in his buttonhole sympathetically drooping, Members halted on their divers ways silently to press his hand, a touch of sympathy more eloquent than flow of words.

Business done.—All within space of half-an-hour. Premier announced that next week and till further notice sittings will be limited to Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday.

THE RETIRING SERGEANT-AT-ARMS.

(Sir H. D. Erskine).

Thursday.—House learns with profound regret that after the last day of May Sir David Erskine will cease to be Sergeant-at-Arms. For forty years he has been a familiar, and popular, feature in the Legislative Chamber. Speakers have come and gone; Ministries have been created and dissolved; the Sergeant-at-Arms has for more than a generation filled the Chair by the Cross Benches below the Gangway. His ancient office is a thing apart. It is the last link of the personal relations of the Sovereign with the faithful and, in Stuart times, the occasionally refractory, Commons. Members are elected by the people. They in turn elect the Speaker. The Sergeant-at-Arms is nominated by the Sovereign, to whom alone he owes fealty.

Sir David Erskine has worthily upheld the dignity of the office. A strict disciplinarian, jealous for absolute obedience to the rules and traditions of the House, native courtesy and a natural kindness of heart have kept him clear from reproach of offence. When for the last time he has lifted the Mace on to the Table or replaced it on the brackets, his name and personality will remain a tradition round which memory will pleasantly linger.

Sat till 9 o'clock. Quite unusual in these times. Occupied chiefly by debate on famous contract for purchase of wood made by Board of Works with firm of Meyer and Co. Young bloods on Ministerial side smell a rat. Handel Booth in particular sees it moving in the air. Has conducted inquiry of his own into circumstances. Complains that patriotic effort has been baffled by tactics of that Machiavellian personage, First Commissioner of Works, Lord Emmott.

"Only one new thing I did discover," said Handel. House instantly assumed attitude of profound interest. "I discovered," he continued in tone calculated to make the flesh creep, "that there is in the Office of Works in close touch with Mr. Meyer's firm a brother-in-law of his partner."

Member for Sark disposed to ask what relation would he be of Mr. Meyer. Tommy Lough, who constitutionally objects to private Members criticising their pastors and masters on the Treasury Bench, protested against this "stabbing, prodding the Government in the back."

"Why in the back?" asked Handel.

"Because you sit behind them," was Tommy's prompt reply.

No getting over that. Amendment negatived.

Business done.—House adjourned till Tuesday.

"I'd like to join the flying corps."

"What!"

"Oh, I mean the chaps wot 'olds on to the flying-machine while the pilot gets into it."

REST CURES.

An Innovation.

We were discussing rest cures, and everyone had a special kind to recommend.

One said that there is nothing like bed. Bed for a fortnight. But that seems to me to need great strength of mind. Personally, my horror of bed after the sun has begun to knock on the windows is only equalled by my desire for bed as the hands of the clock draw near the hour which our lively neighbours (and allies) call Minnie.

Another advised Cornwall and no newspapers. There is something to be said for this scheme. If there were no newspapers, life would be restful automatically. It is the news that wears us out. The advanced age which Methuselah succeeded in reaching was probably due to the total absence of any Euphrates Chronicle or Mesopotamia Mail.

Another suggested a hydro with frequent baths; but would not the atmosphere of the place go far to modify the merits of the treatment?

Another counselled a sea voyage; but the prevalence of frightfulness on and under the ocean has made this a questionable scheme just now.

It was then that I chipped in. "I have discovered," I said, "a new and perfect kind of rest cure. It is simply this: to lend your house to nice friends and then to go and stay with them as a guest."

They asked me to amplify, and amplification being my long suit I gracefully complied.

The merits of the arrangement, I told them, should leap to the eye. To begin with you are at home, which is always more comfortable than an hotel or a hydro or anyone else's house. Hotels, to take one point only, disregarding their fussiness and restlessness and the demand made upon one to instruct foreigners in English, cannot cook or prepare the most important articles of food for those in need of repose—such things as bread and butter, boiled potatoes, mint sauce, horse-radish sauce (they often do no more than shred the horse radish and pour cream over it, the malefactors!), roly-poly jam pudding, bread-and-butter pudding, Yorkshire pudding. When it comes to grills, they can beat the private kitchen; but again and again the private kitchen beats them, and always in the essentials.

As for hydros, let us forget them, I said. And as for other people's houses, however comfortable they may be, they lie under the charge of being not your own. They have to be learned and there is not time to learn them. One is on one's best behaviour in them, and that is contrary to the highest restfulness.

One's own home, I went on, is not necessarily perfect; but quite a number of its drawbacks are removed when someone else is occupying and running it. Take the inevitable item of bills. Here my hearers all shuddered, and very rightly. Bills lose much of their minatory aspect when they are being paid by others. The disturbing thought as to the ruinous cost of butchers' meat which assails one directly the cover is removed no longer has any power to vex. The sirloin still represents too massive a pile of shillings, but the shillings are to come from other pockets—always a desirable state of affairs. Coal again. In one's own house normally one trembles, and particularly so just now, every time the poker is used; but in one's own house when one is a guest how blandly one stirs the embers into a richer glow.

Life can be made enormously more piquant in this way. Indeed it can really become worth living once more. One settles down in one's own well-tried chair; one looks round the room at one's own pictures and books; and all the time the coal that burns so fiercely and consolingly in one's own grate is being paid for by others. No stint either! Could there be a more delightful arrangement?

The disabilities of the scheme are trifling. It is, of course, a bore to find that one's private bath-time has fallen to the temporary owner, or that lunch is now half-an-hour earlier; but these are nothing. The great thing is that one is a guest here at last—that after years of striving to make both ends meet and having all the anxiety on one's own shoulders, suddenly it has gone; and when, instead of the modest claret which is all that one's own cellar can normally be induced to disgorge, however one may search it, the new occupants are found to be in allegiance to "The Widow," the rest-cure is made complete. Here, one says, is the solution. Now will I be reposeful indeed.

"That is my discovery," I concluded. "I made it a few weeks ago and I shall never forget it. All that one has to be careful about is the choice of friends to whom to lend the house."

"But supposing," someone asked, "they don't invite you to stay with them—what then?"

"That," I said, "would be awkward, of course. In fact it would ruin everything. But one must be clever and work it."

"How did you get your invitation?" another inquired.

"If you'll borrow my house, I'll show you," I said.

"A few days after we saw some deserters come in from the desert."

Daily Dispatch.

Native troops, we presume.

"The Kronprinz Wilhelm risks interment."

Daily News.

If the Crown Prince gets killed many more times he will not only risk it but get it.

"Stolen or strayed, from 51, Port-Dundas Road, Scotch terrier, answers to Mysie; if found in anyone's possession will be soverely dealt with."—Glasgow Citizen.

Poor Mysie may well say, "Save me from my friends!"

"Andler having explained the decifision to Leben, who knows English imperfectly, the prisoners then bowed to the magistrates and returned to the cells."

Liverpool Daily Post.

Andler must have found his gift of tongues severely taxed.

Bloated Loafer (who has talked of nothing but his wealth for the last hour). "Beastly rough luck—two of my cars are under repair; andother one's bein' painted. I've only got the little one to go about in!"

Artist. "I know the feeling, old chap; I was poor once myself."

TOTAL PROHIBITION OF ADJECTIVES.

(A Journalistic Dream.)

AT THE PLAY.

"The Panorama of Youth."

A first-night audience, largely made up of distinguished actors and actresses, gave a friendly reception to Mr. J. Hartley Manners' new play at the St. James's Theatre. The author calls it "a comedy of age," but it might be more fitly styled "the tragedy of an auburn wig." Sir Richard Gauntlett, widower, after a married life wrecked by the faithlessness of his wife, recovers hope, and imagines that he has recovered youth, in the smiles of a charming widow, Mrs. Gordon-Trent. So he dons the wig and a pair of stays two sizes too small for him, and blossoms forth as an Adonis of twenty-five, much to the disgust of his friends and contemporaries, Gladwin, retired soldier, and Carstairs, ex-diplomatist. They are possibly more disgusted by the dithyrambs on the joys of youth which Sir George Alexander has to deliver. Felicia, too, Sir Richard's convent-bred daughter, who worships the memory of her mother, is horrified at the thought of her father marrying again. She is a in love with Geoffrey Annandale, whose mother has also kicked over the matrimonial traces—a secret which he imparts first to his fiancée and next to her papa. Then in walks Mrs. Gordon-Trent, and she, as you will have guessed, is Geoffrey's peccant mother.

In the Third Act Felicia makes an impassioned appeal to her father not to marry the sinful lady, and stings him into the revelation that her own mother had not been a saint either. But the excitement, or the pressure of those stays, is too much for a weak heart, and he collapses on the sofa. Both engagements are now off.

In the last Act Gladwin and Carstairs, dyed and corseted to match their old friend's whim, arrive at Gauntlett Abbey, to find him recovering, but minus the auburn wig, the trim figure and the illusions of youth. After them comes Mrs. Gordon-Trent, determined to reunite Felicia to her Geoffrey, and incidentally Sir Richard to herself. As no one could resist Miss Nina Boucicault she has her way.

The play, it will be gathered, is of the stage stagey, but the acting was excellent—notably that of Mr. Alfred Bishop and Mr. Nigel Playfair as the elderly friends; of Miss Madge Titheradge as Felicia, and of Mr. Owen Nares as Geoffrey. When the speeches have been judiciously pruned and the action tightened up, The Panorama of Youth should make a pleasant enough entertainment. But we respectfully suggest that if the auburn wig were made a shade less luxuriant and the stay-laces slightly relaxed, Sir George Alexander's part would gain in probability. L.

O to be in Hampstead when the grapes are ripe!

Adolf Mr. Leon M. Lion.

Luke Sufan Mr. Sydney Valentine.

"Advertisement."

There is very little excuse for a Revue unless it makes you laugh, and Mr. Macdonald Hastings' production in this kind at the Kingsway is not nearly as funny as he could have made it, for he has the true gift of humour. I call it a Revue—though it was not advertised as such—because it reproduces and combines nearly all the popular features of recent plays. There is the Young Man who is Not on Good Terms with his Reputed Father (Searchlights); the Jew of Commerce (Potash and Perlmutter); the American Get-rich-quick Method (passim), and the Gallant Young Second Lieutenant (everywhere). All these features are represented in Advertisement; and I might, if I were in a captious mood (which is far from my thought) throw in the Rehearsal for the Accolade, which recalls The Twelve Pound Look. In detail Mr. Hastings follows most closely the lines of Searchlights. There the Reputed Father hates the Son; here the Son hates the Reputed Father; in each you have the Mother's peculiar devotion to her Son, and her confession of her relations with the Lover, now dead; in each the damning proof is provided by a portrait which appears to be the Son's but is really the Actual Father's.

But the play is not without signs of originality. Thus, the hero was never once shown in khaki on the stage. This novelty, however, is mitigated by the appearance of a rather subordinate character in uniform of this material with red collar-tags. He steps straight out of a newspaper office into a Staff appointment. Another sign of the creative faculty was to be seen in the character of the Jew father, Luke Sufan. Starting life as a struggling musical genius, he developed commercial tastes, devoting himself to the exploitation of Sufan's Staminal Syrup ("you pay a dime and drink a dollar"), which brought him a fortune and even the menace of a knighthood. It also acted as a little rift within the violin, which ultimately made the music mute and killed the man's soul. This is certainly a new touch. Men have often sacrificed other arts for lust of lucre, hut there has never come within my knowledge any previous case of a man's sacrificing the art of music for the profits of a patent medicine.

The Christian wife, who had married him in early days for joy of his violin, was soon driven by his brutality into the protective arms of an old lover, from whom she returns home in time to bear her husband a son that isn't his. Sufan takes a high paternal pride in him, educating him above his sphere, and receiving open contempt in return. The curtain rises upon the boy's twenty-first birthday, which is celebrated by a dinner-party given to the advertising clique who have helped to boom the Syrup, the father's object being to bring home to his son the humble origin of his exalted prospects. The boy admits to his mother his instinctive disgust at his father's tastes, and she responds by admitting the hereditary cause of this unfilial attitude.

In the next Act, the sudden news of the boy's death in the War, arriving in the midst of a commercial séance, throws Sufan into a paroxysm of grief; but the ruling passion is strong upon

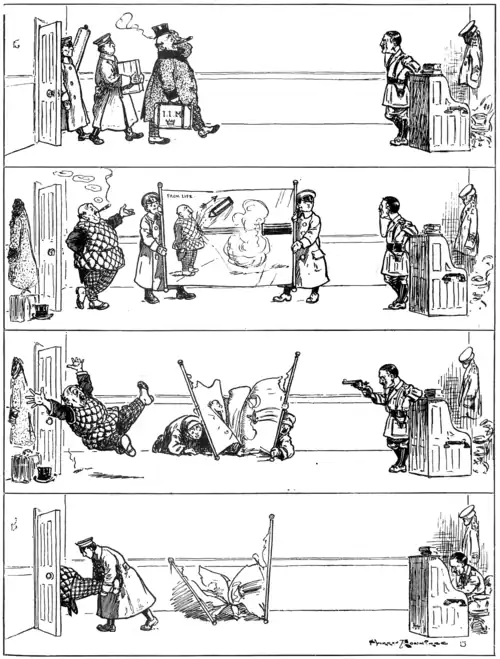

WHAT THE WAR OFFICE HAS TO PUT UP WITH.

II.—The Inventor of the Bullet-Proof Cuirass.

him, and he recovers sufficiently to receive a representative of the Press; and, seeing a chance of making capital out of his son's gallant death, he bribes the interviewer with a five-pound note (I have never done this myself, nor seen it done) to include in his report a reference to the hero's father as the creator and proprietor of Sufan's Staminal Syrup.

It is not till the War is over (and apparently forgotten) that he learns the facts about the boy's fatherhood. Among the few virtues that he has retained (including a fluent familiarity with Holy Writ) is a strong predilection for chastity, and he is extremely annoyed. His wife leaves him; he throws up the Syrup and the chance of a knighthood and resumes the violin habit. Finally, in his old age she gets in touch with him again on the roof of a Garden City, where he is keeping the Feast of Tabernacles in a summer-house hung with very unlikely grapes; and the prospect that "at eventide it shall be light" is symbolised as the curtain falls by her readjustment of his disordered neckwear.

As to the main purpose of his play, Mr. Hastings has gone the way of least resistance in justifying his title. Something worth while might have been told us about certain secret methods of advertisement; but the ways of the patent-medicine-monger have been too freely exposed. Something again (though perhaps not very fresh) might have been made out of the tendency to snobbery in the attitude of a boy toward a father who has educated him above his own station; but when he is actually the son of somebody else, the fault may be ascribed to heredity, and no moral is to be got out of that.

For the rest, apart from the Jew's character, which owes much of its air of originality to its mixture of incredibly inconsistent qualities, the play is largely a rechauffé. There are strong scenes, but they are not always grounded upon humanity. Thus, though the father's tears over the death of his son caused us great embarrassment (the sight of a grown man shaken with grief is always a terrible thing), it was modified by a suspicion of insincerity, for he had never given any proof of deep affection, but only of a parvenu's pride in his boy's superiority. And when this suspicion was rudely confirmed by his prompt effort to secure a commercial réclame from his affliction, we felt that the author had trifled with our emotions.

Mr. Hastings has shown himself capable of much better work than this; and if he succeeds now he will have his cast to thank for it. Mr. Sydney Vallentine was brilliant. There was little trace of Hebraism in his accent, and he glossed over the thinness of many passages by extreme rapidity of speech; but he got every ounce of strength out of the stuff he had to play with. Miss Lilian Braithwaite brought a very perfect dignity and sweetness to her difficult part as the wife. Miss Ellen O'Malley showed great tact and charm in the pleasant interludes, too brief, in which she was allowed to play a minor rôle. Mr. Arthur Chesney, as the funny man among the advertising agents, was obviously prepared to be funnier still if he had been given the chance; and Mr. Athol Stewart as the representative of The Daily Passenger, who took a Staff appointment during the War, and made the very slowest kind of love before and after, was a pattern of stolidity. As the Jew's Secretary (with an eye for a stunt) Miss Violet Graham had little to do, but I should never think of asking for a prettier typist. Finally, as Adolf, who played the piano and accompanied the Jew's violin (not to be confused with the Jew's-harp) when it was in use, and served, when it wasn't, as a loyal, if acquisitive, butler, Mr. Leon Lion gave a clever performance in the Perlmutter manner. As a right Semite, Adolf had strong views on mixed marriages and did his best to confound the intrusive Gentile. He it was that, by his wicked manipulation of their correspondence, delayed the reunion of the severed couple. But Sufan was also to blame. When a man takes the trouble to have his letters registered in order to ensure their delivery he might take the further trouble of posting them himself, instead of leaving them to the care of a suspected menial. And so, of course, he would, except in a play, where the course of true love, and even of untrue (as here), must not lack for artificial corrugation.

O. S.

THE DYSPEPTIC'S DILEMMA.

Jellaby is one of those miserable crocks whose diseases are so vague and uninteresting that nobody will listen to them. Nobody, that is, who can help it.

Since the War began he has been worse than ever. Though I constantly reassure him as to the state of my memory, he never fails to give me his long list of reasons (some of them quite repulsive) for not enlisting.

If I was only moderately fit," he says, "I'd have enlisted ages ago. But a chap with my liver———" (Here follows a lengthy and fluent dissertation on dyspepsia in general and liver trouble in particular.) "So it has come to this," he concludes: "I force—positively force—my breakfast down every morning, and then comes that dreadful feeling of repletion as soon as I leave the table."

Once I asked him what his doctor said, and Jellaby flared up immediately.

"Brown!" he cried. "That fellow knows little and cares less about dyspepsia. Told me there was nothing wrong, the great beaming apple-faced brute! Said I was to take plenty of hard exercise and laugh a lot. Laugh! The man's a blithering idiot."

Now Brown is an old friend of mine, and a practical adviser if ever there was one. I felt sure that Jellaby was concealing something, and I took the first opportunity to tackle Brown on the subject.

"I've just been talking to a patient of yours," I began; "chap called Jellaby."

The Doctor smiled. "Ah!" said he. And how is Mr. Jellaby this morning?"

"Mr. Jellaby," I said, "is too dyspeptic to serve his country. He had quite a lot to say about it."

The Doctor's smile broadened. "And had he nothing to say about me? I suppose that professional etiquette forbids me to ask you, but———"

"Jellaby considers," I announced with relish, "that you are a blithering idiot."

"And I told Mr. Jellaby," said the Doctor, "that if he really wants to cure his dyspepsia his best plan will be to———"

"Not enlist?" I cried.

"Just that," said the Doctor.

United Service.

"Lord Kitchener fopen to interviewers in ———'s outfitting window has proved a great attraction. He is now displaying Navy Serge Suits."—Shepton Mallet Journal.

We do not pretend to know what "fopen" means. But the rest of the paragraph is easily intelligible, and we foresee that a jealous Admiralty will soon be exhibiting khaki in its windows.

The Somnambulists.

"When fire broke out early yesterday at the City Hall, Glasgow, where 200 recruits are billeted, the sleeping men were paraded and helped to extinguish the flames."

Daily Mirror.

"Scandinavia has no doubt that in the latter half of last week a naval engagement took place between Great Britain and Germany in the North Sea. The evidence is that of kippers who, using their eyes and ears, put two and two together."—Star.

From the very first the story was regarded as fishy.

Fond Mother. "Well, good-bye, my dear boy. Take good care of yourself; and, whatever you do, always avoid trenches with a North-East aspect."

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Long Furrows (Mills and Boon) is a story that I ended by liking much more than I hoped to at the start. It might have been called a Book for Mothers; I certainly never read a tale more maternal. The special mother of the argument is Mrs. Lane, who lived at Clifton and had a son named Robin and a candid friend named Brenda. The thing starts with Mrs. Lane going to a Founder's Day at Clifton College, and not enjoying herself, partly because Robin would not come with her, partly because she had a foreboding. Which was explained later when she returned to hear from Robin that he had been stealing from the bank at which he was employed, and that there was nothing for him but disgrace and flight. So the two, mother and son, fled together, and, after a tragic odyssey, eventually brought up at a little secluded cove in Cornwall, where in the end happiness found them—I shan't tell you how. Not quite a cheerful book, as you see. Wasn't it Mrs. Cragie who said somewhere that "Mothers are ominously silent concerning the joys of existence"? In a way that might perhaps be the view of Mrs. Fred Reynolds. But not, I think, altogether. The whole treatment of the relations between Esther Lane and her son is very delicate and true. Now I will tell you that what made me think I wasn't going to like the book was the conversation of the Clifton masters at the Speech Day function. Especially one who had dreamy eyes, and, looking at a field full of boys, said suddenly, "What are we doing for them?" Much have I travelled in the realms of pedagogy, but I have yet to meet a schoolmaster who would say things like that. And before a parent too! Fortunately this palpable creation of the lady novelist makes but a fleeting appearance. And the other characters are far more genuine.

I have just read The Salamander (Secker) of Mr. Owen Johnson—a name new to me and one to keep on the select list—and I feel I know just all about one side of that city of surprises, New York. The Salamander is either a native of New York or a migrant thither from a Western State. It is of the so miscalled gentler sex, of any age from eighteen to nominal twenty-five. It plays with fire to the extent of eating it and living on it—that, roughly, is Mr. Johnson's idea. It can (as the saying is) take care of itself. Naturalists observe that it has a long head and a little heart. Quintessentially a cold and dishonest reptile, it offers all and gives nothing in particular in exchange for anything from "bokays" to automobiles. Beginning with male flappers, preferably the young of plutocrats, it later fastens on the plutocrats themselves or their robust enemies. Strong men, at whose nod railroad and chewing gum trusts go quaking, fight publicly over it in equivocal restaurants. Mr. Johnson's particular salamander, Doré by pseudonym, eschews the rigour of the game. She allows herself to be hard hit, and, instead of running away with the hitter, is betrayed by a maternal instinct (with which she has, properly speaking, no business) to take unto herself a young rotter with a determined spark of character glinting behind his eyes, who has for her fair sake fought himself free of the widow Cliquot and others. This, I suppose, is a concession to the molasses formula, though our author is too sincere a person to accept it, and hints in an epilogue that burnt salamanders don't dread the fire as much as it would be comforting to their converted husbands to believe. This clever novel hasn't the air of caricature which the subject might seem to invite. Doré herself is made plausible enough—no mean feat. Salamanderism is presented as a phase of the new feminism in U.S.A. An allied species has been reported in Chelsea by detached observers.

In Mr. P. W. Wilson's War study, The Unmaking of Europe (Nisbet), there is presented, together with a broad statement of the circumstances leading up to the final crash, a narrative of the events of the first five months of the struggle. The author's work has this to recommend it, that he has really succeeded in his effort to be fair (the effort is almost too visible at times), and that his manner of writing is nearly always sufficiently flowing to carry one without impatience over ground that is necessarily quite familiar. Not only does one naturally remember all the incidents related, but even the phrases in which they are told come forward, time and again, with something of an air of old acquaintanceship; yet this lack of novelty, inevitable, I suppose, in a history made by the week, seems to detract very little from the strength or even from the vividness of the book. Perhaps the impression of freshness is derived a good deal from those pages in which Mr. Wilson, leaving the plain pathway of official reports to wander among the philosophies, comes to matters that are intriguing because they are controversial. His suggestive analysis of the reasons for our attitude towards Russia, for instance, is well worth study, and I should not have grumbled at rather more of this sort of thing, which indeed the title had made me expect; but I suppose it really could not be done in the time. We should all have listened with attention to P. W. W. commenting, say, on the uncanny inactivity of the House of Commons, a subject that must have had a certain painful attraction for him. His work is to be continued, and I should like to think he will find material for only one more volume, but I shall look out with interest for as many as his subject gives him.

The excellent message which Mr. Justus Miles Forman attempts to convey in The Blind Spot (Ward, Lock) is that all movements for social amelioration must be inspired by love and compassion, and that the mere brainy organiser will fail. Arthur Stone, taking an exactly opposite view, affirms that it is the emotional element which has been so disastrous and sterile in progressive movements, that common-sense alone is the essential factor; and even goes so far as to denounce the self-sacrifice of those brave souls in the wreck of the Titanic who made way for the saving of useless steerage lives which would likely enough be perpetual charge on the state! Also, when a chance offers to save a beggarman from a runaway van he deliberately refuses to risk a life so valuable to the community as his own, and leaves the rescue to his rival, Coppy (who carries off the girl in the end); and when Stone, following up these two unpopular adventures, lets himself go bald-headed at a public meeting for all the things that simpler folk reverence he gets the push direct from his immense body of supporters and goes out a broken man. Perhaps Mr. Forman makes him rather too blind and too spotted for plausibility, while Coppy Latimer, occasional abstainer and delinquent, had the turning over of his new leaf made rather too easy for him. Still, both Coppy and his author have their hearts in the right place, and even Mr. Sidney Webb would have lost patience with Stone.

Though one may be inclined to think that Cornwall is in danger of being written to death, a welcome can still be offered to Cornish Saints and Sinners (Lane), which (as I discovered rather cleverly, for the fact, though stated, is not exactly proclaimed) is a "new edition." Mr. J. Henry Harris has a real love for his subject and a true understanding of the Cornish people; and as his book has the additional advantage of numerous drawings by Mr. L. Raven Hill I can recommend it emphatically to those who seek Cornwall not only for its golf and its cream and its alleged resemblance, in climate, to the Riviera, but also for the charm of its legends. I could wish that Mr. Harris had confined himself to a mere narration of the tales he has collected, for some of the comments made upon them and put into the mouth of Guy Moore are terribly facetious without being funny. This, however, does not materially affect the value of a praiseworthy and successful attempt to do justice to the Duchy.

"'Arf a pound of steak, an' mother says, please cut it tough, as we've got one of Kitchener's armies billeted on us!"

WORDS TO A WAR-BABE.