Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3848

CHARIVARIA.

The Kaiser has been presented with another grandson. It has not yet been broken to the poor little fellow who he is.

⁂

What, we are asked again, has become of the German Crown Prince? According to our information the Kaiser consigned him some time since to a place the name of which has been censored.

⁂

The Austro-Hungarian army authorities have condemned 75,000 pairs of boots destined for the troops, the soles being found to consist of paper. Austria, like its distinguished ally, will have nothing to do with scraps of this material.

⁂

"The Germans," writes a correspondent from the French front, "have done much in Champagne which they will regret in their sober moments." We believe it.

⁂

A shocking case of ingratitude has come to our notice. Mr. Irvin S. Cobb, the American journalist, after being an official guest of the German Army at the Front, has issued an account of his experiences under the title The Red Glutton.

⁂

The Berliner Tageblatt states that four English trainers have been released from the concentration camp at Ruhleben. This is supposed to mark the Germans' appreciation of our decision not to abandon horseracing.

⁂

A number of German prisoners of war are, it is announced, to be interned in the Crystal Palace. Our ambition, we understand, is ultimately to find palaces for all of them.

⁂

"THE CARPATHIANS FIGHTING,"

announces a contemporary. We have heard of mountains "skipping like rams." Now, apparently, they are butting one another

⁂

"RHINO FIGHTS FOR GERMANY."

Daily Express.

We must keep a Watch on the Rhino.

⁂

German aviators have been dropping more bombs in the sea. They seem to be getting a little careless.

⁂

According to Le Matin, a German Staff Officer recently confessed, "We have lost the rubber." And he might have added, "We also have a difficulty in getting the copper."

⁂

"HEADMASTER OF ETON AND

GIBRALTAR"

Daily Mail.

We think this headline is scarcely fair to Dr. Lyttelton. He particularly does not wish any Englishman to be master of Gibraltar.

⁂

Ready shortly, by Dr. Lyttelton, a brochure entitled, "On the importance of saying what you mean, and meaning what you say."

⁂

Meanwhile we are informed that the outbreak of German measles at Eton has nothing whatever to do with the Headmaster's famous utterance.

⁂

In London, we learn from The Daily Mail, classes are being organised to teach women "how to do the grocery trade." This looks like retaliation.

⁂

"Mr. Stephen Scrope," says The Liverpool Daily Post, "has deposited an additional £500 for the first vessel to sink an enemy submarine with 'The Yorkshire Post.'" We should have thought that one of our quarterly Reviews would have been better adapted for the purpose, and we shall be surprised if The Yorkshire Post does not resent this insinuation of heaviness.

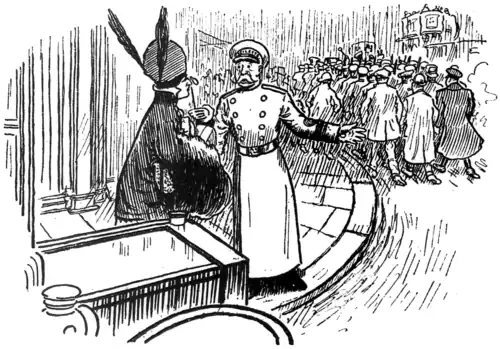

Lady (who has spend some time in the shop). "Where's my chauffeur?"

Commissionaire. "Just this moment joined, Madam."

"The Red Cross Ladies, by working in shifts, are able to keep the buffet open from 6 a.m. until midnight."―The Times.

Surely an inadequate costume.

What the "Star" Saw.

"Simultaneous with the resumption of the Allies' attack on the Dardanelles over the Gallipoli Peninsula, and from the mouth of the Straits, the Russian Baltic Fleet yesterday successfully bombarded the outside forts and batteries of the Bosphorus."―Star.

Our evening contemporary is the only journal to record this remarkable long-range performance―accomplished, we presume, with "star-shell."

Burning Questions.

"Fellow-Traveller Wanted, who was in 3rd class smoking compartment 9 p.m., King's Cross to Hitchin, Thursday, Jan. 14, 1915. Identification circumstance, who saw gentleman alight at Stevenage, and whose lighted match was blown on advertiser's overcoat; Urgent Appeal."―Morning Post.

As far as we can gather from this advertisement, which is not so illuminating as the subject demands, the incident affected three fellow-travellers, of whom two were ignited, and only one, the advertiser, is known to have been put out. The fate of the other who was last seen "alight at Stevenage" can only be conjectured.

"There is no 'h' in the Russian alphabet. Therefore the Russians spell Hartlepool 'Gartlepool' and call Field-Marshal Hindenburg 'Gindenburg'... and why we continue to miscall a town which is both written in Russian and pronounced Harkoff 'Kharkov' is more than one can tell."―Sunday Times.

At last we thought we had got the key to Russian phonetics, but this last sentence snatches it all away again.

Several correspondents have written to to tell us of the shocks they received on seeing this startling newspaper bill:―

"RUSSIANS

MARCHING

ON

PALL MALL."

Some of them feared that our Allies had suddenly turned round and become our invaders, while others found in the announcement a comforting confirmation of the hopes they have secretly cherished ever since the great Russian rumour first got afloat.

"Drogheda has sent many soldiers to the battlefield, but the marital spirit is not yet exhausted."―Drogheda Advertiser.

Three cheers for the brave wives of Drogheda!

BLOOD-GUILT.

[To the employers of the men who sank the liner Falaba and laughed at the cries and struggles of drowning men and women.]

IN THE MATTER OF A COMMISSION.

I've had to get rid of my Commissionaire because he was an ex-Sergeant Major. I found myself standing to attention and waiting for permission to fall out after requesting him to post a letter. I felt impelled to salute my articled clerk and my youthful nephews when I met them in the street. The climax was reached when I was actually slanged in a recruit squad by my dismissed office-boy, who is home from the Front on sick leave. The only remedy that appeared feasible was to secure a commission myself.

I broached the subject to a Territorial Colonel who was at that time a friend of mine. He said he wasn't forming a cricket team, but that if he had been in want of a slow bowler he would have been delighted to recommend me.

The next man I tried was also a Territorial Colonel. He had known my mother, but had no knowledge of me personally, so there was no excuse for his behaviour.

"I think you knew my mother." I said.

He was a man of caution and wanted to hear her name before committing himself. Judging that prevarication was useless and liable to lead to suspicion I disclosed it.

"I knew her well," he admitted, and held out his hand.

"What can I do for you?" he asked.

"I am my mother's son."

"I guessed it."

"I have been given to understand that there is a war on and that this country is involved."

"I have heard the rumour."

"No doubt. These things to get about. Even the Press had got hold of it. I shouldn't be surprised if there are questions in the House on the subject."

"I think that we may assume that this rumour is not without foundation. What then?"

"It seemed to me to be the kind of thing one ought to be in, and that as you are, in a sort of way, a friend of the family, I couldn't do better than have you as a Commanding Officer."

"You will find the Recruiting Sergeant on the next floor―second door on the left. To avoid mistake my orderly will show you the way." He rose, and out of compliment to my prospective C.O. I rose too.

"Then I may take it that I shall be gazetted in due coure. I hope that it won't be too soon as I have one or two things I should like to arrange."

"Oh, you want a commission?" We sat down again.

"That was my idea. I hadn't thought of serving in the ranks as my friends tell me that I should be wasted there, and seeing that you knew my mother the position might be a little embarrassing for both of us. I thought of taking a position as a Quartermaster."

"Any experience?"

"Not very much to speak of."

"How much?"

"I once spent a week with an Army crammer, but we didn't get on well together. He didn't understand my French."

"A Quartermaster's duties are rather technical."

"I have some legal experience. I am rather good at filling up forms. I have a light style which goes down pretty well. I should like you to see some of my correspondence with the Inland Revenue people―I fancy you'd like it. I think that I shall get the better of them if I can keep the matter going for another couple of years. Of course it's early days yet―the matter has only been under discussion for four years―but they've already shown distinct signs of weakening. So in case of any little argument with the County Authorities or the War Office———"

"Any other qualification?"

"I'm pretty good at games. I write a bit―hardly enough to be a vice. I've appeared on the boards as an amateur and have escaped matrimony."

"I'm afraid I haven't a vacancy for a Quartermaster at the moment."

"If you're already suited I don't want to press the Quartermaster job. In a crisis like the present one ought not to be too particular. I should even be prepared to take an ordinary commission, though I can't say that I care much for walking."

"Any military experience?"

"Well, I once wore a sword at a fancy-dress ball. After I put it in the cloak-room at the urgent request of the stewards it only ruined one silk hat, and that was the fault of the attendant, who didn't understand swords. Of course I've played soldier parts. One of my most successful rôles was a peppery colonel."

"How old are you?" my I was afraid that he would ask my age, as it's my one weak spot from a military point of view.

"Does one have to justify any statement as to age?" I asked.

"A birth certificate must be produced."

"That's awkward. The only one I've got gives the impression that I was born in 1875. I've always had my doubts as to its accuracy, as I can't say that I recall the event. They do make mistakes at Somerset House. I might get them to alter it, but they're rather fussy and dilatory, and one can't expect the War to last for ever. I must look into the matter and see if I am justified in amending it myself. Suppose we say born in 1885; that only means altering one figure."

"I'm sorry I haven't a vacancy. I've applied for more officers already than I'm strictly entitled to have."

"Then one or two more or less won't matter. I presume the War Office don't trouble to count up the number of officers in all the Territorial regiments. When an inspection is threatened you might give a few of us leave, so as not to overcrowd the parade. I shouldn't be upset at being left out of it. When shall I join?"

"After the War, when we shan't be so busy."

He looked at his watch and manœuvred me through the door into the passage, where I tripped over a sentry.

A GREAT NAVAL TRIUMPH.

German Submarine Officer. "THIS OUGHT TO MAKE THEM HEALOUS IN THE SISTER SERVICE. BELGIUM SAW NOTHING BETTER THAN THIS."

Charles. "Mummy, I love you more than Lois does. I love you 100 and 1,000 and 100,000."

Lois. "I love her billions―I love her the whole world."

Charles (in a disgusted tone.) "I don't love her the whole world. I don't love her the Germany part."

AT THE FRONT.

(In continuation of "At the Back of the Front.")

Weeks and weeks ago a German battery got the range of a slab of railway from which our armoured train had been grieving them; and but for the fact that the train had moved off about half-an-hour earlier it might quite easily have been hit. The German battery was so pleased at this victory that they now make a hobby of this bit of the line, dusting it up daily from 5 to 7.30 P.M.; and I should think it would be very dangerous for anyone who was actually present at that hour. But, as nobody ever is, our casualties at this point are negligible. In the meantime the noise is horrid; and our billet has already thought out several polite notes to the battery commander, pointing out that we like to make up lost sleep between tea and dinner. The only difficulty is in the matter of delivery.

In the There was a time when the trenches were as restful as billets; such halcyon days are gone. An offensive attitude is demanded. We must, it is felt, prove to the Bosch our activity, our confidence in ourselves, our contempt of him, and, in short, our höchste Gefechtbereitschaft (all rights still reserved). To achieve this without actually attacking takes a bit of doing. A specimen of demonstrative operations ordered during twenty-four hours may, without giving too much away, be briefly sketched:―

4 A.M. Alternate platoons will sing God save the King, Tipperary and The Rosary until 4.15, and alternate sections will fire one round rapid. Should the Bosch disregard this―

6 A.M. Swedish drill will take place on the parapet. This having failed to draw fire or other sign of hostile attention―

10 A.M. The regimental mouth-organist section will play the Wacht am Rhein flatly, timelessly, tunelessly, but still recognizably. When both sides have recovered―

5 P.M. Two companties will fire salutes at the setting sun, while the remaining two will play association football in front of the barbed wire.

By some such policy of frightfulness we daunt the Bosch from day to day, and we have small doubt that on that afternoon when we go "over the top" to take tea with him he will meet us halfway with raised arms and a happy smile of relief at the ending of his suspense.

'Variæ Lectiones.

Underneath a picture representing a soldier jumping from the ground on to a trotting horse:―

"A well-known French jockey, now galloper to a French General, setting off in haste with an important message."―Daily Mail.

"Convalescent British and French soldiers amused at the antics of Daix, the well-known French jockey, who entertained them with an exhibition of trick-riding."―Daily Graphic.

"The man who stole the tyres of Mr. Eggar's brougham at the Pegu Club (or anybody else) can have the whole Turn-out (brougham, horse, harness, coachman and syce) for Rs. 750, because the owner is fed up about it."

Rangoon Times.

An old brougham and a clean sweep.

A TERRITORIAL IN INDIA.

VI.

My dear Mr. Punch.,―At last I am back again in the regiment, and the office, now a thousand miles away, is a dwindling memory. The thing was done in typical Army fashion. One day last week the four of us who had been left behind at Divisional Headquarters put our heads together and decided that as there was every prospect of our remaining where we were for a long time we might reasonably expend a portion of our scanty pay in the purchase of a few minor aids to civilised life, such as plates and cups. Before we could set out for the bazaar, however, there came a precise official intimation that, as it had been found impossible to relieve us, we must be prepared to continue to serve in the office indefinitely.

That altered matters. A few months ago we might have been deceived, but we know the Army now. We abandoned our shopping expedition, gathered together our scattered belongings and prepared to depart. Sure enough there came next day imperative orders for us to rejoin the battalion at once.

As you have often pointed out, human nature is a perverse thing. For over three months we had been longing and agitating to be returned to our regiment, as soon as the instructions came we regretted leaving the office. We began to lament our cosy little tent, our comparative liberty, the civilian friends we had recently made, and we looked forward darkly to an era of irritating bugle calls, stew and kit inspections. We remembered, too, how far behind our comrades in military efficiency we were bound to find ourselves―and there is no mercy in the Army.

But our last hours were cheered by a letter from Mahadoo, formerly our "boy." I transcribe it for you literally:―

Respected Sir,―I beg to ask that your my Masters Please honour will you kindly Sir I work with your before Alik come about five days go that please Sir did not Paid me that money yet I did not ask that to you Because Alik did not me my pay I hire for I am sorry thank verry much to you please excuse me the all turbully

I am your Poor Obedent Servant

Mahadoo Butler.

I need not burden you with details of Mahadoo's claim, but you will rejoice to know that we were enabled to leave him satisfied and beaming. And we assured him it was no "turbully."

This, by the way, was our first intimation that we had all this time been employing a butler. The knowledge was rather staggering at first, but now we are beginning to realise its possibilities in future years. "Ah, yes," one will be able to say, "when I was staying in India, you know, my butler came to me one morning..." But we shall, of course, studiously refrain from mentioning that the butler used to clean the boots, make the beds, wash the clothes and perform other inferior domestic duties.

Forty of us, who had been collected from various points, made the journey up together. Being merely British soldiers, we were given the worst available accommodation (that of course is our opinion; soldiers are built like that), with the result that five of us found ourselves in a grimy and malodorous compartment, measuring exactly seven feet by four, and austerely furnished with two extremely hard wooden benches a foot wide and three hat-pegs.

But it was quite good fun. By day there were innumerable fresh and exciting things to see, while by night the problem of sleeping kept us in paroxysms of laughter for hours. It is not easy, you know, to arrange twenty-nine feet of humanity on fourteen feet of bench. We contrived to relieve the congestion to some extent by improvising a hammock from a blanket and some pieces of string. It was a fine test of soldierly intrepidity to sleep in that hammock. I occupied it for one night, and I can tell you I envied those lucky fellows safe in their trenches at the Front.

We spent three days and nights in the train, and at the end left our little wooden hut with regret.

So here I am, back in the dear old Army again, welcomed with the same old Army greeting: "Hullo! You back? Got a cigarette?" Nothing is changed. On the day we arrived we were marched down to the Quartermaster's Stores to draw our bedding. The Corporal in charge of the party halted us, told us to wait a minute and went inside. Half-an-hour later he emerged with another Corporal, and both of them, after telling us to wait a minute, disappeared round the corner. An hour passed. Then the Quartermaster-Sergeant appeared and demanded to know what we were waiting for. We explained wearily. "Wait a minute," he said, and went back inside. An hour later he returned, looked us up and down and asked what the devil we wanted. Again we explained, and again he enjoined us to wait a minute, and disappeared. We cooled our heels for another hour and then sprang to attention as the Quartermaster himself came on the scene. "What do you men want?" he demanded testily. "Come to draw our bedding, Sir," we cried in chorus. "Oh, it's no good your coming today," he exclaimed. "Come back to-morrow."

Dear old Army!

But perhaps there are indications of a kindlier feeling among the N.C.O.'s. I have as yet no kit-box, and a kit-box is essential to a man's peace of mind in barracks. In a moment of forgetfulness I mentioned the fact to a Sergeant and asked if I might have one. As soon as I had done it I realised my mistake; but to my surprise, instead of paralysing me with a stony glare, he looked quite sympathetic. "I know it's awkward without one," he said, and passed on. Even then he seemed to feel he had not done all he might, for, turning round, he added with an air of kindly consolation, "Still, you've got your padlock and key, haven't you?"

Yours ever,

One of the Punch Brigade.

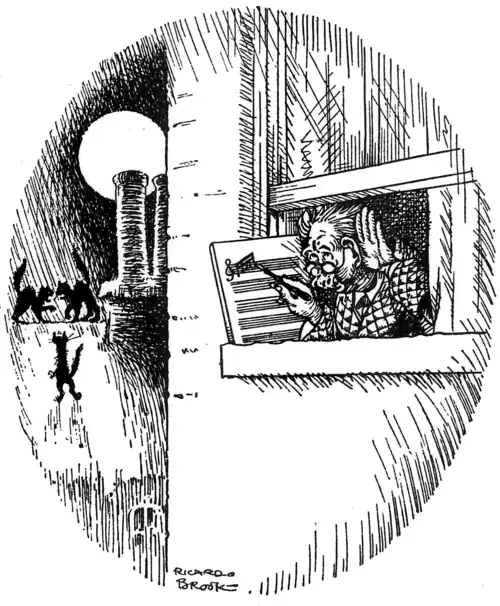

German composed seeking inspiration for melody to a "Song of Hate."

Mistress. "Afraid of the Zeppelins? Don't be stupid, Mary. The Master's going out after them."

NEW PAPERS.

[One noteworthy feature of War-time has been the production of a number of fresh journals. But it must not be supposed that they have all been issued on our side, and a glance at the announcements here following will prove that the same spirit of enterprise animates both enemy and neutral countries.]

LAND AND UNDER WATER.

Published by

Hohenzollern and Tirpitz.

A Simple Competition

in which valuable prizes are offered for the best new terms of abuse for application to England.

THE AUSTRIAN ECHO.

Edited by Francis-Joseph Hapsburg.

Berlin private wire.

Special Notice.―The Proprietors of the above Journal beg to intimate that their Przemysl Branch Office has been closed until further notice.

THE CRESCENT MOON.

A Monthly Revue, edited by

Enver Bey.

The Magazine of the Constantinople Smart Set.

"In and Out of Town" is a regular feature, read by all wishing to know the movements of Stamboul Society.

Special Notice.―The Advertisement Manager would respectfully point out to House Agents having desirable seraglios to let in Asia Minor that a Unique Opportunity offers.

ROME CHAT.

The only Paper Read throughout Europe.

Published weekly in Neutral–tinted Wrapper at No. 1 Via Media, Rome.

THE TRANSATLANTIC SPECTATOR.

A pro-British-German-American Review.

Edited by Professor Woodrow Wilson and published weekly at The White House (semi-detached). Washington.

"The authorities in Rochdale have up to the present declined to restrict the hours during which licensed houses are open, though on several occasions they have been urged to take this step by temperature organisations and other people, but the matter has now been taken out of their hands."―Rochdale Times.

The temperature organizations will now perhaps turn their attention to the weather, which always wants somebody to look after it.

"London, March 4.―Discussing the fall in London of flour prices, Mark Lane, the noted merchant, said yesterday:―'Every shot fired in the Dardanelles is a shot fired into the Chicago wheat pit.'"

Los Angeles Daily Times.

This may be Mark's opinion, but we should like to hear what his equally noted brother, Mincing, has to say about it.

U29.

By K 9.

I am one of the unhappiest of creatures, because I have been misunderstood. Nothing is worse than to mean well, and do all you can, and be misunderstood beyond any possibility of explanation. That is my tragedy just now, and it all comes of having four legs and no articulation when the people who control things have only two and can express themselves.

Sirius, how I ache! But let me tell you.

I am a performing dog―nothing more and nothing less. I belong to a man named―but perhaps I had better not give his name, as he might be still more cross with me, especially as he does not come too well out of this story. And when I say I belong to him I mean that I am one―the principal one―of his troupe; but of course I could leave at any moment if I wanted to, and it is extremely likely that I shall. I have merely to run off the stage, out of the door, and he would be done. I have not done so yet, because hitherto he has treated me quite decently, and I enjoy my performance. I like to see all the happy people in front, and watch their amazed faces as I go through my wonderful tricks. "Isn't it extraordinary?" they say to each other. "Almost human. Fancy a dog doing that!" It amuses me to hear things like that. We never say, we dogs, that clever human beings are almost canine. We know that to be absurd; they would never be within miles of being canine.

Anyway that is what I am―a very brilliant performing dog, with a number of quite remarkable tricks and the capacity to perform as many again if only my master would think it worth while to add to his list. But so long as there are so many music-halls where his present performance is always a novelty―and there are so many that he could be in a different one every week for the next ten years if he liked―why should he worry himself to do anything fresh? That is the argument he uses, not being a real artist and enthusiast, is I am, and as is one of my friends in the troupe too. She, however, does not come into this story.

I don't know whether you know anything about music-halls, but it is my privilege to be in one and perhaps two every day, entertaining tired people, and the custom now is, if any striking news of the War arrives during the evening, for one of the performers to announce it. Naturally, for human beings like being prominent and popular as much as dogs do, a performer is very glad when it falls to him to make the announcement. Applause is very sweet to the ear, even if it is provoked merely by stating the heroism of others, and it is not difficult for anyone accustomed to hear it to associate himself with the action that has called it forth. I feel that I am very rambling in my remarks, but their point must be clearly made, and that is that the privilege of telling the audience about a great deed just now is highly prized, and a performer who is foolish enough to miss the chance is stupid indeed.

I must now tell you that my master is not the most sensible of men. It was clever of him to become possessed of so able an animal as myself and to treat me so sensibly as to induce me to stay with him and work for him; but his cleverness stops there. In private life he is really very silly, spending all his time in talking and drinking with other professionals (as they call themselves), and boasting of the success he has had at Wigan and Plymouth and Perth and places like that, instead of learning new jokes and allowing me to do new tricks, as I should love to, for I am tired of my present repertory and only too conscious of my great powers.

It was on March 25th and we were performing at a popular London hall; and just as we were going on someone brought the news of the sinking of the U 29. I heard it distinctly, but my master was so muzzy and preoccupied that, though he pulled himself together sufficiently to say "Good business!" in reply, he did nothing else. He failed to realise what a chance it was for him to make a hit for himself.

Look at the situation. On the one hand the audience longing to be cheered up by such a piece of news, and on the other a stupid performer too fresh from a neighbouring bar to be able to impart it or appreciate his luck in having the opportunity of imparting it and bringing down the house. And not only that. On the other hand there was a keen patriotic British dog longing to tell the news, but unable to make all these blockheads understand, because with all their boasted human knowledge and brains they haven't yet learned to know what dogs are talking about. Would you believe it, my master began his ancient patter just is if nothing had happened? I tweaked his leg, but all in vain. I snapped at him, I snarled at him, to bring him to his senses; but all in vain.

Then I took the thing into my own paws. I ceased to pay him any attention. All I did was to stand at the footlights facing the house and shout at to the audience again and again, "The U 29 has been sunk with all hands!" Come here, you devil," said my master under his breath, "and behave, or I'll give you the biggest thrashing you ever had." But I didn't care. I remained by the footlights, screaming out, "The U 29 has been sunk with all hands!" "Mercy, how the dog barks!" a lady in a box exclaimed. Bark! I wasn't barking. I was disseminating the glad tidings.

"Silence, you brute!" my master cried, and brought down his little whip on my back. But I still kept on. "They must know it, they must be told!" I said to myself, and on I went with the news until at last the stage-manager rang down the curtain and our turn was called off. But a second later he was on the stage himself, apologising for my conduct and telling the audience about the U 29, and in their excitement they forgot all about their disappointment at not seeing me perform. Their applause was terrific.

"See what you missed by your folly," I said to my master. But he paid no attention, he merely set about giving me the thrashing of my life.

Sirius, how I ache!

COLOUR-CURE.

["Colour has a wonderfully beneficial effect on criminals and lunatics. But of course the colours must be blended with scientific exactness till they harmonise absolutely with the temperament of the patient. Some colours, used alone, are absolutely poisonous."

Interview in "Daily News."]

From a Scilly Islander.

Extract from a letter to The The Royal Cornish Gazette:―

"The Hun pirates have begun their deadly work. Cannot our English men-of-war be on the look-out for them?"

We have much pleasure in bringing his valuable suggestion to the attention if Mr. Churchill and Lord Fisher.

THE REWARD OF KULTUR.

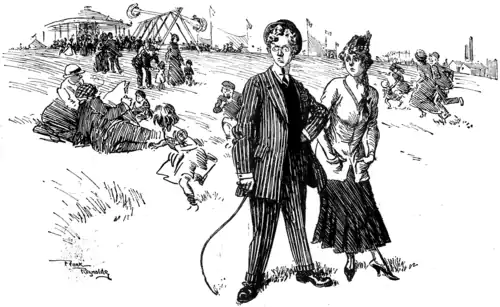

She. "Look here, George, I'm going 'ome if you're going to talk about the War all the time! If you feel so pent-up, why don't you go an' 'ave a shy at the coker-nuts?"

MANY A SLIP.

I think I have mentioned Jessie as a champion cup-crasher before. There are people who can drop cups and glasses without breaking them. Jessie can break them without dropping them. It is a gift, and she has it. She has other gifts, including that of kindness to Peter, and these have prevented our side-tracking her so far.

Alison has tried to cure her by threats of dismissal, but threats only encourage Jessie to higher flights of smashing. She knows by now the low breaking strain of vegetable dishes to an ounce, yet in her daily intercourse with these utensils she cheerfully subjects them to such stress as would shatter a brick. With cups and saucers I think she must practise secret jugglery in the pantry.

Every month-end, or nearly so, after Alison has paid her wages, she says, "Jessie really will have to go; two more plates broken and another badly cracked;" or "The handle has been knocked off the Lowestoft jug; Jessie says she was dusting it, and it simply dropped off;" or "Poor Aunt Emily's present [a Dresden group] has lost an arm."

Last Saturday night I felt that the climax had been more than reached. Peter found the base of our only Venetian glass vase, the pride of the combined family heart, under the drawing-room sofa. The rest of it had disappeared into the dust-bin.

I traced in the air the letters J.M.G. Alison asked what I meant.

"Jessie Must Go," I said impressively, "before she makes another raid on our unfortified crockery."

"I suppose so," said Alison wearily. "But really I don't know where I shall find another maid like her."

"I don't want you to find another like her," I said. "I want you to find someone as unlike her as possible. She's an image-breaker, an iconoclast. I begin to suspect her of being of German extraction. Give the girl an Iron Cross and let her go."

"You forget," said Alison, "that she is simply invaluable with Peter."

"True," I said, "she is kind to children. Well, she shall have one more chance."

*****

Sunday passed off quietly. Jessie spent her spare time knitting socks for soldiers. My witticism about her breaking the Sabbath was not so well received as I thought it deserved.

On Monday evening when I arrived home, Alison looked so down in the mouth that I felt sure there had been another breakage, a bad one, and I was right.

"Let her have her passports at once," I said, "for goodness' sake. She's breaking up the happy home on the instalment plan."

"No," said Alison firmly, "I can't give her notice this time."

"Then come and watch me do it," I said. "What's she broken?"

"It's rather a nasty breakage, too," said Alison.

"Come," I said, "out with it. Not any of the Chinese dessert service on the dresser; not the———"

"No," said Alison, "she was saving Peter from falling downstairs and—"

"Well," I said.

"She slipped," said Alison, "and broke her collar-bone."

*****

And now Jessie is a heroine, and when she returns from hospital with the medal for personal bravery she will be firmly established for ever in our household, with licence to break whatever she chooses.

"The use of steel for the making of guns was begun by Alfred Krupp, the master of Essen, probably the ablest metallurgist that the world has ever seen. He died long ago, and Sheffield knows many of the secrets that died with him."—Glasgow Evening Times.

These dead secrets always somehow get about.

THE REVERSION.

Turkey. "I'M GIVING UP THIS BED, WILLIAM. WON'T YOU TAKE MY PLACE?"

Old Lady (to parson—a perfect stranger—who has joined the New Army). "Well, my lad, isn't this better than hanging about street corners and spending your time in public-houses?"

ON THE SPY-TRAIL.

III.

The man who transferred the "prize bloodhound" to Jiminy met him one day. "Hello, sonny," said he, "what luck did you have with the 'what-is-it'?"

Jimmy showed him Faithful, who was lying curled up on the ground.

"You don't mean to say so!" exclaimed the man. "A Persian, too!" He then said, "Poor puss"—just like that, you know—and put his hand down to stroke Jimmy's bloodhound. Old Faithful uncoiled slowly, saw the man's hand, sniffed at it, didn't like it and so just bit it to make it go away. Jimmy says the man looked touched and a cloud settled on his face; then he shot out his foot towards Faithful. He was trying to show Faithful how to do the goose-step, Jimmy says.

The man recommended some different kinds of food for Jimmy's bloodhound; you got them at the chemist's and had to sign a paper for them. He said that if Jimmy showed Faithful to the chemist it would be all right, he would quite understand.

Since then Jimmy has painted a sign which tells you to beware of the dog. The milkman told Jimmy he ought to have another sign with "The Dog" painted on it, and fix it round Faithful's neck, so that there would be no mistake.

One day, when Jimmy was going to unchain his bloodhound and again hurl him upon the spy trail, an incident happened that would have quite unsettled for serious work any but a really well-trained sleuthhound. A fierce chicken which belonged to the man next door had broken loose and, dashing through the hedge, had come right up to where Faithful was chained. Faithful was just finishing his breakfast, and the chicken tried to wrest from him a cold potato he was about to tear to pieces.

Jimmy says the chicken growled at Faithful and began opening and shutting the feathers on its neck at him like an umbrella. Jimmy says you shouldn't do that to bloodhounds; it's dangerous. It made Jimmy's bloodhound pounce like anything, and every time he pounced the chicken jumped up in the air and waggled its feet right at him. Once the chicken crowed straight in Faithful's face. It was awful, Jimmy says. Faithful without any hesitation gathered himself together and rushed behind his kennel to get a good run at him, when the chicken seized the potato with all its might.

Faithful kept leaping and straining at the chain like anything, Jimmy says, for there was the chicken swallowing great lumps of the potato and stretching its neck to ease them down. It kept going red in the face at him, Jimmy says, and his bloodhound hurled himself about with such force that he thought the chain would break.

The chain held all right—the man Jimmy bought it from said it had been tested up to two tons—but Faithful made such a terrific rush that he slipped clean through the collar. Jimmy says he ought to have tied a knot in Faithful's tail and then it wouldn't have happened.

The next door garden is a big one, and the chicken and faithful had it to themselves. They used a good deal of it, Jimmy says. The chicken kept jumping in the air with its feet tucked up to put him off the scent, but old Faithful never faltered, he kept on doing the side stroke, baying steadily. The chicken moulted a good deal during its progress; Jimmy says it was because it got so hot.

Once they passed the fowl-house, and as soon as the hens caught sight of Jimmy's bloodhound they all began to send out the S.O.S. signal, and then the man came out.

Jimmy knew the man a little; he had told Jimmy the day before that snowdrops were harbingers. The man knew all about bloodhounds with chickens, Jimmy says, but his slippers wouldn't let him; they hadn't any heels and kept coming off in the soil. Jimmy says the man went on talking to himself over his slippers and looking for something to throw. But there were only the snowdrops, so he wont to the coalhouse as fast as his slippers could go.

Jimmy says the man wasn't a very good aimer, although Faithful gave him every chance. Faithful kept fetching the coal back for the man and then putting the chicken up again, but the man didn't hit the chicken once. Jimmy says the man had just emptied a little heap of gravel out of his slippers that he had forgotten about for the moment and was taking a very good look at Faithful when the man's wife came out and began to talk to him from the doorstep.

She said his name was Alexander and that he had to come in―did he hear her?―with coal at 30s. a ton. But the man had reached out too quickly to stroke old Faithful with his foot, and Faithful was busy trying to make the man's slipper growl at him in one corner of the lawn. Jimmy says the man is a good hopper, you could tell that from where he left his slipper when he did it. It was like swimming with one foot on the bottom, the way the man did it, Jimmy says, and when Faithful saw the man beginning to do that at him he couldn't bear it and went away. Jimmy says bloodhounds are like that, it unhinges them.

The man told Jimmy of a scheme he had for his bloodhound. It would make him look like a sieve, he said. He said Jimmy's bloodhound was an animal.

All this took up time and made Faithful quite late on the trail, and Jimmy was afraid his bloodhound would be too unnerved for really fine work. However, he led him up to the sausage shop, where he caught his first spy, and loosed him there.

Faithful cast about for a little, scratched himself, then suddenly dashed into the shop hot upon the scent of another of those sausages with the red husk. He couldn't reach those in the window, so he went behind the counter and picked up the trail of one that must have been hiding under a glass dish. Jimmy heard the glass dish smash in the struggle. So did the man. He came running into the shop and threw a chopper for Faithful to fetch. Jimmy says the man got very excited and drew a revolver and fired at Faithful, and then shouted, "Mad dog! Mad dog!" as hard as he could.

Jimmy says that people were looking everywhere for the mad dog, and he was glad he hadn't fixed that sign the milkman told him of on to Faithful.

They had to tear the sausage from Faithful's mouth because his fangs were locked. The policeman was surprised at the sausage, Jimmy says; he said it was a wolf in sheep's clothing. That was because it contained a bundle of new bank-notes, done up in oilskin, instead of proper sausage dough.

Jimmy said it was a fraud, and the policeman said the banknotes were also, he thought. But he was so pleased with Jimmy that he played him a tune on his whistle.

Faithful followed all the policemen into the shop―you see he had tasted blood―and while the policemen went to talk to the man he kept the sausages at bay. He rustled them about a good deal, Jimmy says, and kept daring them to bite back at him.

Jimmy says his bloodhound got so exhausted with his work that he soon had only strength enough to lie down near a pork pie and place his tongue against it

It was not the same kind of spy as the other one Jimmy's bloodhound tracked down; it was a naturalised one.

Jimmy says they used Faithful as a bit of evidence, and the policeman had to swear he was a dog within the meaning of the Act.

Jimmy says the man made banknotes as well as sausages―better, the magistrate said. The man didn't want people to know he made bank-notes, so he put them in a sausage skin, and another man used to come and take them away. He was a confederate, like you have when you do tricks, Jimmy says.

The man kept the bank-note sausages under a glass dish so that they wouldn't stray away and mingle with the others.

The magistrate said that you couldn't always tell sausages by their overcoats. Some of them were whited sepulchres. The bank-notes were for a fund to aid German spies, and so they couldn't be sent by post, as the letters might be opened and the bank-notes leak out.

The man who used to come for the bank-note sausages has not been caught yet―he is still at large; but then so is old Faithful, Jimmy says.

"You started before I was ready. I'll have the law of you for this!"

"Now then, old submarine―none of yer frightfulness!"

In a recent issue we quoted the order issued at an Indian camp that "any Volunteer improbably dressed will be arrested." Judging by the following extract it would appear about time that the military authorities at home took similar action:―

"The greater portion were clad in khaki, some were in blue, whilst others wore semi-military dress. A section of the men wore greatcoats and ordinary caps―one man had donned a Trilby and another a felt hat, while a Morecambe company wore mittens."―Daily Dispatch.

In Scotland things are even worse, for we read in the prospectus of a certain Volunteer Training Corps that―

"It is proposed that the only uniform to be worn to begin with shall be a Hat (conform to Regulations) and a Brassard to be worn on the left arm."

FLOREAT ETONA.

Old Gentleman (discussing man in father corner). But surely, though he hasn't enlisted, he's doing his bit somehow―National Defence, perhaps?―or Special Constable?"

Companion. "The blighter don't do nothing, I tell yer. Nothing! Don't even pull down the winder blinds!

MORE WORK FOR WOMEN.

[It is suggested that one reason for the German hate is the beauty of English girls compared with the maidens of the Fatherland.]

We understand from the news in the daily papers that the distinguished Roumanian, Mr. Take Jonescu, has been urging the Roumanians to join the Allies. Isn't it about time they took Jones' cue?

PRICES AS USUAL.

"Everything is dearer!" shs said, flinging the butcher's book from her.

"Not everything," said her husband gently, while preparing himself to meet a possible demand for an increase in the allowance for housekeeping.

"I don't mean tobacco; I am speaking of necessaries," she replied. "At the grocer's, the baker's, the fruiterer's, the butcher's―wherever you go it's the same; and it has come to this, Rowland, that it is impossible for me to manage———"

"Have you tried Tomkinson's Stores?" he asked.

"That smelly place with a post-office behind the cheeses? No, thank you! And, anyhow, their prices are sure to have gone up like everybody else's."

"They are not all up, my dear; you must try to be less sweeping in your statements. As a matter of fact I looked in at Tomkinson's on my way home and found them quite reasonable."

"Rowland! Do not tell me that the chocolates you buy me about twice a year come from that horrible shop."

"I am sorry, Nora, but I did not buy chocolates; July the 19th, you must remember, is the next date for chocolates."

"Then what could you want to get at Tomkinson's? One thing is certain, if you ask me to eat any of it we shall quarrel. What did you buy?"

Rowland felt in several pockets, his wife watching him closely. At the end he produced a packet of post-cards.

Help!

Under the heading of "Literary Help" this Answer to a Correspondent appeared recently in T.P.'s Weekly:―

"H. L. G. (Bristol).―Your three songs are as good (perhaps a little better) than (sic) many efforts of the kind. You don't attempt to say anything beyond the commonplace, but it is something to achieve the sentimental commonplace without falling into pathos (sic)."

The Literary Helper's estimate of the relative values of "sentimental commonplace" and "pathos" is at least as good as his grammar.

"Sergeant Tisdale received a bullet in the log."―The Observer.

We have always thought it inadvisable for a soldier to keep a log. It is really sailors' work.

EPISTOLARY FRENCH.

"Oh dear," said Francesca in a tone of deep depression, "I've got to write two letters in French."

"It is," I said, "a punishment for having wasted your time in early youth. During the hours nominally devoted to French you were thinking of hockey or bicycles or poetry. Instead of attending to the irregular verbs you were preparing a speech on the subjection of women. And now you can't play hockey and you don't want to bicycle and you're the despot of your household, but you can't write the simplest letter in the French language without groaning and tearing your hair."

"All that," she said, "is very eloquent, but it isn't very helpful."

"I do not pretend," I said, "to be a dictionary or a phrase-book. Short of that, if there is anything I can do you have only to appeal to my better nature and you will find me bubbling over with French of the most idiomatic kind. But tell me, to whom do you propose to write?"

"To Belgian refugees, of course. We must all do what we can to help them, poor things."

"Of course we must," I said; "but do you think our letters will help them much?"

"Well, they want to know things and we're bound to answer them."

"Quite true," I said; "but are you sure that our French will help to reconcile them to living in England? Might it not be of so English a quality that they would feel more than ever that they were amongst strangers? Couldn't we call in person and smile at them and say, 'Oh oui' in a friendly manner so as to make them think they're really at home? I merely throw out the suggestion, you know."

"You can leave it," she said, "where you threw it. It's no use to me. We've got to write these letters."

"Very well," I said, "let's get to work. How shall we begin?"

"'Chère Madame' would be all right, wouldn't it?"

"'Chère Madame' would be simply splendid if the lady is married."

"Married?" said Francesca. "She has been married twenty-four years and has had ten children."

"No one," I said, "could possibly be more worthy of all that is implied in 'Chère Madame'. Let us put it down at once before we forget it."

"Anyhow," said Francesca more cheerfully, "we've got started, and that's more than half the battle."

"Francesca," I said, "you never made a greater mistake in your life. The beginning of a letter in French is, no doubt, important, but it is the merest child's play compared with the end. Are you going to ask this mother of ten children simply to receive your salutations? Or dare you soar still higher and pray her to be well willing to agree the expression of your sentiments the most distinguished? Or to accept the assurance of your most high consideration? You think they're all pretty much the same, but they're not. There are heavy shades of difference between them and you can't help going wrong. Is it worth while to risk exposing your ignorance to a lady who has been married twenty-four years? Pause before it is too late."

"Well," said Francesca, "I can't help it. If ever I get so far in this blessed letter I shall just make a dash for it and ask her to agree whatever comes into my head first. It'll probably be my distinguished sentiments, because I've taken a fancy for that style. It's jolly to think one has such sentiments."

"All right," I said, "have it your own way, but don't blame me if when you next meet her your Belgian lady shows what the novels call evident signs of constraint."

"She won't worry about a little thing like that. She's the dearest old thing in the world, but she's in a great state about the chimney in her sitting-room, which is one of the most successful smokers ever built."

"Hurrah!" I cried, "now we've got the middle of the letter, and that makes it complete. Ramoneur is the French for sweep, so we'll write something like this:—

Chère Madame,

Je vous enverrai le ramoneur.

Agréez, Madame, mes sentiments distingués.

And then you'll sign it and send it off."

"Will that do?" said Francesca. Isn't it just a little too curt? They're our guests, you know, and we ought to do all we can to make them feel at home."

"Well," I said, "we could throw in a few words about the weather."

"But perhaps they don't worry about the weather in Belgium."

"Then it'll be something new for them. And you might add some neat little sentence about hoping that the children are all in good health."

"Neat little sentences," said Francesca, "don't grow on gooseberry bushes, but I'll do my best. That polishes off number one. Now we must consider number two. This time I have to answer a daughter. Somebody, it appears, has been good enough to indicate to Papa a place where he can procure himself cheaply a summer costume made to measure, and it pains them to see Mamma without a suitable dress at a moment when nature is adorning herself with her most beautiful attire. Can I say where Mamma can obtain a dress which will restore her peace of mind?"

"Francesca," I said, "this does not concern me. It is too sacred. All I can do is to suggest that couturière is a not inappropriate word. And this time you can finish up with the assurance of your highest consideration."

"It sounds haughty," said Francesca, "but I'll chance it."

R. C. L.

LINES ON A RECENT CORRESPONDENCE.

FOR THE WOUNDED.

Mr. Punch begs to recommend his readers for their own sakes and for the sake of the cause to attend and bid at the remarkable sale which is to take place at Messrs. Christie's (8, King Street, St. James's Square) on the first five days of each of the weeks beginning April 12th and 19th, and also on the 26th and 27th. Over 1,500 generous donors (including the King) have presented art treasures and relics of unique historical interest to be sold for the benefit of the British Red Cross Society and the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem. The entire proceeds of the Sale—no charge for their services being made by Messrs. Christie—will be handed over to these Societies. The exhibits will be on view from April 7th.

THE TRANSPORT SOLUTION.

"The man you ought to see," they told me, "is the Transport Officer, Southern Barracks."

I found him seated in a large chair in a small oflice. "I have come," I said, "to enlist your sympathy."

"It is yours," he replied, handing me his cigarette-case.

"Also your assistance."

"Ah!" he said sadly, and waved me to a seat.

"Though not myself a military man," I continued, "I have for some time past been working under the military authorities, who are removing me next month, with my wife, children, furniture and other household effects, to a sphere of usefulness on Salisbury Plain. For purposes of furniture transport they created for me some time ago a niche in the Allowance Regulations, which entitles me to free carriage of goods to the amount, on my own account of one ton, on that of my wife of 5 cwt., and on that of each of my two children of 1 cwt.―a total of 1 ton 7 cwt. Our united furniture, however, weighs in all 1 ton 7 cwt. 5 lb. On the other hand, on the occasion of our last shift it only ran to 1 ton 5 cwt. What I want to know is, will the Transport people in consideration of the previous shortage, include the extra 5 lbs. this time in the move? Their net gain on the two events would still be the carriage of 1 cwt. 107 lb."

I drew a deep breath and leant back in my chair.

He sighed, and for a while we smoked in silence. Then he spoke.

"The fact is," he said, "Transport is not really my job. They have only roped me in for it temporarily. Would you mind if I called in my clerk? "

"Not at all," I answered. He pressed a button and his subordinate appeared, a short, spare, disagreeably intelligent-looking man.

"Er―would you mind―er―?" said the Transport Officer to me.

I drew a second breath, a little deeper, if anything, than the first, and re-stated my case.

"What can we do for this gentleman?" asked the Transport Officer.

"Nothing, Sir," said his clerk stonily.

"Can we send him to anybody else?"

"Yes, Sir, we can send him to―" a peculiarly sinister expression flitted across his face―"the A.A. and Q.M.G. at the fort."

"Thank you," I murmured.

"I was afraid," I said, as the man left the room, "that he was going to mention another person, inhabiting a less respectable locality."

"I'm not sure," replied the Transport Officer thoughtfully, "that it doesn't come to much the same thing."

It took me half an hour to reach the fort, situated at the summit of a long hill, and another half-hour to reach the A.A. and Q.M.G., situated at a massive leather-topped table. There was no suggestion, with this officer, of sympathy or cigarettes. He had a very brief manner.

"Yes," he said, as I entered.

I stated my case.

"That all?"

"Yes," I answered; "can you manage it?"

"No."

At the door I paused and turned. "I forgot to mention that I am prepared, if necessary, to carry the matter to the House of Lords."

"What?"

I repeated my remark.

"You'd better go and see the O.C.A.S.C.," he said.

I descended the hill and finally succeeded in discovering the official habitat of the O.C.A.S.C. He was out. Would he be in again? Probably. When? Impossible to predict; would I wait? I would wait. A clerk led me gently into an inner room, placed a Bradshaw near my hand, and left me. As I perused the volume I grew more and more surprised at the undoubtedly wide circulation which it enjoys. The plot is trivial; the style, though terse and occasionally epigrammatic, is unrelieved by dialogue of any description; and it is impossible, without keeping at least three fingers in the index, to gain an adequate idea of the doings of any of the characters. After about an hour I rang the bell and asked for an A.B.C. At the end of the second hour I had committed to memory the populations of all the more important towns in the Home Counties. Just as twilight fell the clerk returned and told me that the O.C.A.S.C. had arrived. I followed him into another apartment.

The O.C.A.S.C. was wandering rather aimlessly about his office. "Did you want to see me?" he asked absently.

I stated my case.

"It's a most extraordinary thing!" he exclaimed, coming at last to a standstill.

"What?" I inquired.

"Where my matches get to," he replied. "I wonder if I might trouble you just to help me find them?"

We took a long time over it, since it had not occurred to him to look in the right-hand pocket of his coat. At length, however, I discovered them there. He was very much obliged to me. "And now tell me what can I do for you?" he said. I re-stated my case. He listened attentively. "I am afraid," he said, "that this will have to be referred to the War Office. I must ask you to put it in writing." I sat down and stated my case in writing.

"Thank you," said the O.C.A.S.C.; "I will communicate with you when I hear their decision, which I hope will be favourable."

As I went out I saw him putting the document carefully in the right-hand pocket of his coat.

A week passed, two weeks, three weeks, but I did not hear from him. Finally relief came from a quarter which I had overlooked. I wrote at once to the Transport Officer, the A.A. and Q.M.G., and the O.C.A.S.C.

"Sir,―With reference to our conversation of the 18th ult., I have the honour to state that the question which you were good enough to discuss with me on that date has been satisfactorily settled by the arrival of a third member within my family circle. Since this entitles me to an additional 1 cwt. of transport, I need not trouble you further in the matter. Both mother and child are doing well, thank you. I have the honour to be, Sir,

Your obedient Servant,

Sempronius Smith."

Not one of them wrote to congratulate me.

LAUGHTER AND DEATH.

"4/- Postal Order sent with worn Umbrella to Betts, Stephens Green, Dublin, will be returned same day equal to new."

Irish Daily Independent.

It is something to get the money back, even if the umbrella is not recovered.

THE MILITARY SPIRIT.

Boy (echorting sheep). "Left! Right! Left!―Left!―Left!"

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

I must say that I found You Never Know Your Luck (Hodder and Stoughton) a great disappointment, the greater from my previous pleasure in the work of Sir Gilbert Parker. I do not object to it as formless, though it certainly is that, or as told in a confusing haphazard style. My complaint is that a fairly effective short story, based upon an unconvincing but mildly dramatic situation, has been inflated to the dimensions of a novel. For five pages of a magazine I might have been entertained to hear how Crozier had run away from the just anger of his wife, after breaking his promise not to bet; how she wrote him an angry letter, which he kept unopened for years (but there is no magazine published that could make me believe that); how the wife had really had a bit on of her own, and how, when she turned up to find Crozier recovering from gunshots and stumped for want of the ready, she steamed open the old envelope, put her own bet-gotten gains therein, and pretended they had been waiting there for him all the time. But as a grown-up book I could hardly think that this justified its author's reputation either in plot or characters. These last by the way have been quite delightfully illustrated in colour by Mr. W. L. Jacobs, who might surely have been mentioned upon the title-page. I am reminded, a little inconsequentially, of the lady who liked Botticelli's Birth of Venus, all but the central figure, which she found "rather a pity." Remembering Sir Gilbert's distinguished work in the past, I can only call his latest story rather a pity. But there may well be those to whom its appeal will be more successful. After all, you never know other people's luck.

Mr. Stephen McKenna must have been seriously annoyed by the outbreak of a war that has swept away the attention of his public from a subject in which he had reason to suppose it was quite keenly interested. At the same time I am not sure whether he has not something for which to be thankful; for that atmosphere of hazy distance that the curtain of the last eight months has drawn over events even so crude in outline as the activities of militant suffrage has converted into a moderately readable story what must otherwise have come perilously near to being a succession of impertinences. There is so little ambiguity about a date like 1913 that, but for this same curtain, most of us could give a guess as to who was Prime Minister and who Attorney-General at that time; and, on learning that members of their families had been kidnapped as a protest against the rejection of the Women's Suffrage Amendment, could place within quite a small circle the original of that brilliant criminal, Joyce, who planned the abductions, and incidentally won the heart of Toby Merivale, the narrator. We might even have begun to wonder how much was history and how much semi-official aspiration towards future achievement, instead of realising that the author had no purpose more serious than the embellishment of a yarn that should initiate tea-table discussion on the possibilities of The Sixth Sense (Chapman and Hall). It would not be quite playing the game for me to say what is that mysterious extra faculty with which the author has endowed his deliberately effeminate hero, particularly as neither of them seems to know much about it―and no more do I, for that matter. It is enough if I hint that by its timely aid a beauteous heroine is rescued from imprisonment at the hands of the militants, and a happy ending assured. For further details I must refer you to Toby Merivale.

Forlorn Adventurers (Methuen) is a book with many pleasant patches, but also a vast deal of what I can only regard as padding. I am unable to believe that such clever people as Agnes and Egerton Castle could not have told so simple a tale more crisply if they had really wanted to do so. Perhaps my irritation at having to plough through a superfluous number of pages in pursuit of the slender intrigue was intensified by the fact that they had been bound up in a haphazard fashion that always worries me beyond measure. But this by the way. When the Master of Stronaven lost his wife, by divorce, various meddling relations set out to find him another, in the person of the vacuous daughter of an Argentine millionaire. Shortly after their wedding, however, the Master developed heart disease, and, being bored with vacuity, reconciled himself with wife number one, and so died. I am far from saying that the tale is badly told, but I do say that there are too many scenes that retard instead of helping the action. And upon one point I must join issue with the authors. I entirely decline to believe that woman like Mrs. Duvenant, who, in her progress from a small shop to Connaught Place via the Argentine, had mastered at least the elementary rules of behaviour, would have comported herself with such ignorance and brutality in the house where her son-in-law lay on his death-bed. So much for carping. Now let me add that several of the subordinate characters are admirably drawn, especially perhaps Lady Martindale (a portrait-study, I should think, and a clever one). Also that the Scotch and Italian setting is the real thing. But the fact remains that the chief adventurers seem to have been too forlorn for either myself or the Egerton Castles to have been at our happiest in their society.

Despite her preface, which goes some way to disarm the critic, I am bound to say that I think Miss Constance Smedley would have been better advised to change the title of her latest novel, On the Fighting Line (Putnam). I am willing to believe that it was written before the War―indeed the fact is obvious―but when all is said it remains true that for us now there is only one battle, and that subsidiary fighting lines merely exasperate. This, I fear, has indeed been the abiding effect of the book upon me; even its good qualities vexed me that they were not better, and better employed. It is a record, in diary form, of the emotions of a girl typist in a big City office. Dare I confess that I rose from it with a feeling of profound sympathy for the office? Frankly, from almost every point of view the diarist (who has various names, though the junior partner generally called her Jasmine) struck me as unattractive. And most of her friends were even worse. Perhaps in a way I was not wholly free from prejudice. I can never keep a quite impartial mind about book-heroines who make obviously literary records of the emotions at the very instant of experiencing them. Moreover, you will not have progressed very far in this volume before you discover that, under a guise of sympathetic neutrality, you are really (if a man) being held up to ridicule because―you will never guess for what―because you are severe upon ladies who destroy the contents of pillar-boxes. There's a breath from the unregenerate past for you! No. Though I hasten to admit some freshness and charm about the week-end wooings of Jasmine and her junior partner, the story as a whole remains what have called it above―exasperating, because it is about types and ideas with which it is impossible in these big days to feel more than a faint academic sympathy.

Mr. R. Scotland Liddell, who gives us The Track of the War (Simpkin, Marshall), has made a motor tour of Belgium, chiefly in the company of a Belgian Red Cross officer, and has by his quiet modest showing put in gallant piece of work in the matter of relief of the wounded on the somewhat irresponsible plan which the twain adopted, working apparently under no orders but their own. If the book is not a completely satisfactory addition to the serious literature of the War it is because the author does no seem to possess a very judicial mind. He writes in a natural heat of indignation after seeing the traces of German frightfulness; but the case in bulk against the enemy is so unanswerable that what we chiefly need now is especial care never to weaken it by admitting any details without unimpeachable evidence. Our author does not avoid such phrases as "thousands of other instances," nor make allowance for the inevitable distortions of evidence given originally by witnesses distracted with fear and hate, and retailed at second and fifth hand in an unfamiliar language. Mr. Liddell covers the terrible ground―Dinant, Termonde, Aerschot, Andenne, Tamines―and quotes freely the official documents of the Belgian commissions; but adds, for instance in the case of recorded mutilations for which evidence should be still attainable, no first-hand personal testimony which would have given a special significance to his book. It remains a piece of competent but necessarily hurried journalism, not without a sense of atmosphere, and should prove particularly valuable to folk of sluggish imagination, like the Immortal who wrote to Lord Kitchener complaining about the taking off of his favourite train, and the kind of person who still counts it a disaster if the cook spoils the fish.

REMARKABLE CASE OF PROTECTIVE COLOURING.

Owing, it is believed, to the fears of a German invasion, a zebra at the zoo assumes a neutral aspect.

Describing the battle of the Falkland Islands The Great War states:―

"... As the short winter day was drawing in a quick result was needed... But the winter sea was deadly cold."

Of course we knew that the Great War had turned the World upside down, but we had not realised that in the Southern Hemisphere the seasons had actually been reversed.