Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3858

CHARIVARIA.

ALL schoolchildren in Berlin and Vienna were given a day's holiday on the occasion of the re-capture of Przemysl. This makes one wonder whether they were all made to work overtime when the Russians took the fortress.

⁂

By the way, it is not generally known that the name Przemysl is onomatopoeic and indicates the noise the town makes when it falls.

⁂

We must anyhow give the Germans credit for constancy. In spite of the entry of Italy into the War the mass of the Germans are still true to their old hate of our country.

⁂

According to Reuter the Turks have been using wooden shells. It would look as if they were beginning to lose their heads.

⁂

"Paradoxical though it may sound," says the Lokalanzeiger, "Germany is destined to win either way, whether she emerge victorious or defeated from this titanic struggle, and the greater her defeat the surer and more lasting will be her ultimate triumph." In these circunstances it seems rather stupid of her not to give in at once.

⁂

The effect of the hot weather is now evidently being felt at the Front. A recent communiqué wound up with the statement, "On the remainder of the front there is nothing fresh."

⁂

The members of the Coalition Cabinet have decided to pool their salaries with a view to their being divided equally. The sum, we learn from The Express, has been worked out in detail by Mr. McKenna. So much for those who declared that the new Chancellor of the Exchequer would be unable to cope with his duties!

⁂

"Yesterday," says a writer in The Daily Chronicle, "I dropped on the photograph of an American writer on the causes of the war. I mistook it at once for President Wilson's face. But the face was that of Mr. James M. Beck. From the camera's point of view the likeness is surprising—only that the one is a slightly handsomer edition of the other." We suspect that that tactless word "slightly" has annoyed them both.

⁂

"At the Palladium last week," we read, "Mr. Charles Gulliver presented Max Erard, the pianist, with his gigantic cathedral organ, which weighs eight tons." We hope that Mr. Max Erard is not a Lilliputian.

⁂

According to the New York papers the wife of a Methodist minister of Sedalla, Missouri, while cooking eggs for breakfast, broke one, and, seeing some foreign substance removed it, and it turned out to be a scrap from a newspaper. The explanation probably is that it was a duck's egg containing a small canard.

⁂

The cry of "Eat Less Meat" has, we hear, caused no little alarm in canine circles, where it is feared that, if prices continue to rise, humans may discover the nutritive value of bones.

⁂

The newest railway station of the Bakerloo line is staffed entirely by women, and it is proposed to call it Maiden Vale.

⁂

Answer to Lady Correspondent:—Yes, we agree that those respirator-masks are unbecoming to nine persons out of ten and are apt to lead to a loss of individuality, but have you tried the effect of adding a little lace insertion and a few hanging beads?

⁂

We are glad to see that Ireland is Ireland still. The Clerk to the Local Authority, Omagh, publishes in The Mid-Ulster Mail an advertisement which begins as follows:―"Sheep Dealers, and others, are reminded that all Sheep imported into the County from other Counties are required to give to the Sergeant of Police in the District in which he resides, within three days, his Notice of Intention to Dip."

The Salute

To Stout Travellers.

"Tuesday, 8th June, 1915. 'The more waist the less speed.'"

Murray's Edinburgh Railway Timetable.

CASES RESERVED.

["The Government are of opinion that the general question of personal responsibility shall be reserved until the end of the War."—Mr. Balfour in the House.]

ESMERALDA.

A Tragedy of the Artistic Temperament.

When Margot Davenish proved herself unworthy of a poet's homage by her hilarious reception of a proposal of marriage framed in deathless anapaests, Reggie Outhwaite found himself in a quandary. Margot's bright eyes had inspired the rapturous abandon of the early pages of his Purple Passionings, and without her he despaired of completing the volume. As a lover scorned, he realised that tradition called upon him to eschew the society of women; as a writer of erotic verse, he felt that his Muse stood urgently in need of a lady-help.

It was at this crisis that Esmeralda came into his life. She lived at the corner of Bath Street behind the plate-glass of "Sidonie, Robes et Modes," and her mission was to demonstrate the ethereal perfection of Madame Sidonie's creations. Coarser natures lacking the artistic temperament called her a dummy, but at the first glance Reggie knew that at last his prayers had been answered. That night he threw off two sonnets and a virelai before going to bed to dream of her.

Esmeralda was not one of those shameless hussies whose outrageous déshabillé crimsons the young man's cheek. She was a very superior article, fashioned probably in Paris and obviously by an artist. No mere pedestal surmounted by a head and shoulders; as far as the eye could see she was quite all there. She sat in an armchair with one knee crossed discreetly over the other and one dear little mouse of a shoe daintily tip-tilted; toying with her parasol and smiling mysteriously. For Reggie her smile was fraught with all the suggestive allurement of the Monna Lisa. Moreover, in his infatuation, he deemed her eyes a wondrous passion-grey, and grey eyes had always done anything they liked with him.

For weeks Reggie haunted the neighbourhood of "Sidonie, Robes et Modes." He did not care to stand in open adoration, for the window contained other things besides Esmeralda, and he was a man as well as a poet. He would pace slowly past his divinity; then, turning suddenly as if he had remembered something, as slowly retrace his steps. Some days he covered miles in this way. One morning a damsel in black silk draperies whose bearing would have graced a Princess of the Blood Royal moved Esmeralda farther back into the shop, fearing doubtless that her ears would come unstuck under his ardent glances. It was then that Reggie decided that he must buy Esmeralda. With her companionship to inspire his pen he would not disappoint posterity. But the artistic temperament never shines amid the sordid chafferings of the market-place and the thought of the Princess's icy scorn daunted him.

To brace himself for the encounter he took a month's rest at the seaside. Returning full of courage he at once made his way to Bath Street in such a state of elation that blank verse positively streamed from his lips. But a cruel shock awaited him. Where formerly had gleamed the tender message, "Sidonie, Robes et Modes," there now flaunted the vulgar inscription, "I. Isaacstein, Gents' and Boys' Outfitter." Behind the plate-glass there smirked a wax figure clad in an Eton suit. An icy fear gripped at his heart as he stumbled towards the door. What if this upstart tailor proved ignorant of Madame Sidonie's new address! Then, as his gaze fell again on the smirking lad, the truth burst upon him in all its horror, and he sank heavily to the pavement. From out that waxen countenance there smiled a pair of wondrous passion-grey eyes! The incomparable Esmeralda had been melted down to fit an Eton jacket!

Reggie is now a respectable member of society, for in that awful moment the last spark of his poetic fire flickered out for ever. But he never despairs. Often of a Spring evening, when the throstle is calling to his mate and the very air is palpitating with passion, he will sharpen his pencil and bear his swelling heart out into the garden, there to compose an elegy worthy of his lost goddess. His progress is very slow. Hour after hour the pages of his rhyming dictionary rustle beneath his questing thumb, but not yet has he achieved an opening couplet to satisfy his fastidious soul. At present his choice is wavering between

and

He feels both these couplets possess the true poetic touch, the greatness of simplicity; but he cannot make up his mind which of them more accurately interprets the tender melancholy of his spirit.

"Mr. Balfour and Mr. Austen Chamberlain both visited Buckingham Palace and had audiences of His Majesty. The King to-day received the American Ambassador, Mr. Page, at Buckingham Palace. The inquest was adjourned until June 16."

Manchester Evening News.

We have to thank innumerable correspondents who have forwarded the above paragraph, and regret that none of them has been able to throw any light upon what looks like a tragedy. We are happy to state, however, that all the distinguished personages mentioned are still alive.

"Since the war began the honour of being the first airman to bring down a Zeppelin has been eaglerly sought."—The Globe.

The new adverb is excellently appropriate.

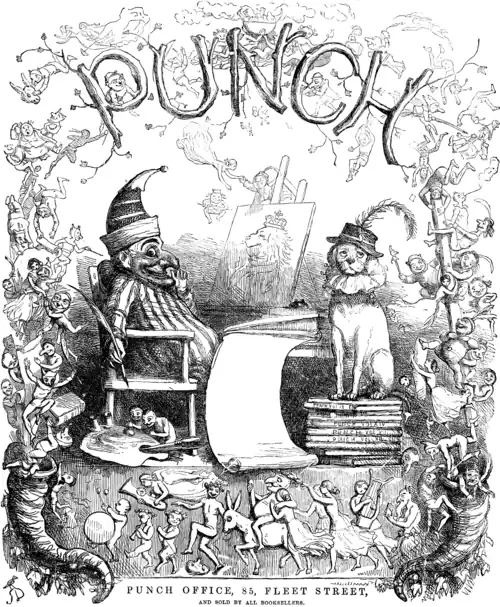

ON THE BLACK LIST.

Kaiser (as Executioner). "I'M GOING TO HANG YOU."

Punch. "OH, YOU ARE, ARE YOU? WELL, YOU DON'T SEEM TO KNOW HOW THE SCENE ENDS. IT'S THE HANGMAN THAT GETS HANGED."

The Deutsche Tageszeitung, remarking on "the black and distorted souls of decadent peoples," issues a warning to Punch and others. "Their performances," it says, "are diligently noted, so that when the day of reckoning arrives we shall know with whom we have to deal and how to deal with them most effectually."

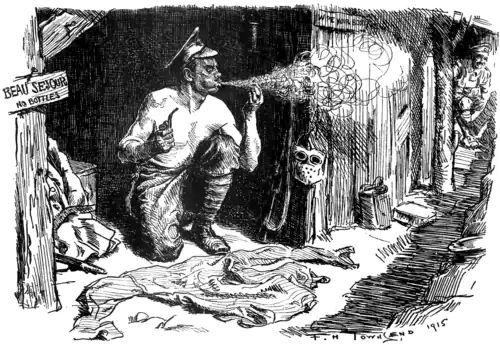

Tommy (who has just caught an intruded and is asphyxiating it). "Nah, then, what abaht yer bloomin' respirator?"

A NEW REIGN OF TERROR.

The other week I had the privilege of laying before the world (or, to be more precise, the threepenny world) a choice example of unambiguous letter-writing on the part of a little Polish tailor. There now arrives the very latest specimen of the Baboo skill in this art; and, as very often happens, the writer is an official connected with a railway. The classic example of Baboo railway correspondence is the frantic telegram about the tiger that was consuming the staff. In the following document we find similar trouble, but the tiger is now a man. An ironical touch to the affair is added by the circumstance that the unfortunate officer in charge who tells the tale had taken command of the assaulted station only that morning. But here is the letter:—

"16th Feb. 1915.

"Further to my code CP of date I hasten to inform you that this noon about 2.30 P.M. I noticed a quarrel just behind this office window. I paid little or no attention to this, but a little later on I heard a great alarm raised from the station platform; rushing out I saw to my great surprise a heap of men in one mass, few bleeding; sticks and fists were freely used. With the help of few passengers I approached the mob, not without fearful beating in my heart, and attempted to separate them in vain, and at the way one burly-looking villain stared at me I left the place, leaving them to their own fate, and got inside the office. I tried every one of the staff to send for the Headman, but none would dare for fear of being assaulted by one who I understand is the bully of the place. Shortly this particular individual rushed inside carrying the door-bar, which he broke off, and used criminal force on me and the booking clerk. He threatened both of us of bodily harm, swearing that he will bring down the whole station apparently for no reason.

"It was far more than what a man alive could have put up with, and but for the timidity of the staff I would have bundled them together. I thought of my firearm more than once. Thanks to Providence, I controlled, although I am unable to say how. He pulled me about twice, and it was my sickness that prevented me from running him down to earth. In the meantime I wired to all concerned. He has also damaged some flower plants, etc. No. 17 Down was due, and when she was approaching the mob dispersed and this burly villain rushed inside again and forced a ticket from the B.C., who very wisely issued it lest he would assault and upset all, for the man appeared very desperate and fearful and did not pay the fare of the ticket. The police arrived and are taking necessary steps. I would like to point out that the life of the station staff here is in danger every minute.

"I took charge of the station only to-day.

"(Signed) O. in C."

The curious thing about this letter is its frank admission of fear. Usually the writer testifies to his own courage and reflects on the pusillanimity of his staff; but here the Officer in Charge, although he admits that the staff was timid too, does not disguise his own reluctances.

But what a first day!

From a stock-broker's circular:—

"You will see that several guilt-edged issues can now be purchased at prices which will yield you over four per cent."

The reference is presumably to the German and Austrian Government stocks.

Voice of Envy. "Garn! 'E ain't no real Bantam! They jest dressed 'im up to kid blokes wot fink they're too little to join."

THE WATCH DOGS.

XXI.

My dear Charles,—Perhaps it is that I have not been quite myself lately; at any rate, whatever the inner cause, a change has come over me and I am no longer able to suffer fools gladly. Between ourselves, I have conceived the utmost dislike for these Germans, a dislike which is all the more remarkable since I happen to be fighting some of them at the moment, and I'm sure that to fight against people is to get to know them better and to appreciate all their good points. However insufficient my data may seem to be, I am convinced that these Teuton fellows are quite impossible, their manner atrocious and their sense of humour nil. I surmise that at their officers' mess they overeat themselves methodically four times a day, making nasty noises. I suspect them of having very ostentatious baths in the morning, at which they are offensively hearty, and yet really, if the truth were known, only wash the parts that show. I can picture them talking exclusively about themselves, shouting down each other and putting such a mixture of superior virtue and patronizing joviality into their morning greetings that the genial and kindly "Gott strafe England" becomes little more than a sullen menace to the addressee. And if they ever do stumble upon a joke, I am quite certain they repeat it ad nauseam and end by quarrelling about its inner meaning. All this I have gathered from the noises they make behind their parapet, and the way they shoot or don't shoot at us. Possibly there is one little group of better men in the middle, by the ruined farm-house, whose sympathies are all with us and who shoot at us only because they must shoot at something, being at war, and cannot shoot at their own people because it would crick their necks.

Having been driven to this opinion of the enemy I have been reluctantly compelled to put a little frightfulness into my personal campaign. With the kind assistance of my men, I have been able so to arrange our rifle fire in my platoon that, at the busy time when everybody who is anybody is firing, every five rifles make a tolerable imitation of a maxim, thus giving the enemy the impression that we have twelve machine guns per platoon, that is one hundred and ninety-two to the battalion. At other times we do an organised sulk, refusing to fire for hours at a time. Nothing is more trying than a silent foe; he's bad enough when he's shooting, but when he's quiet he's very likely preparing something more dreadful, possibly coming across to you in the dark to stick a piece of cold steel into you. And so we get him thoroughly nervous and craning much too far over the parapet, and then we suddenly recover our good spirits and burst into a very rapid fire of our own invention, to a merry sort of syncopated beat.

Another way to punish Germany (by human agency) is to take a couple of dozen empty tins, fill them half-full of stones, tie them together, leaving a very long tail-piece of string, and send the whole out, in the dark, to be placed by an audacious and impudent patrol amongst their barbed wire. You then wait till the quiet time of the next day, and when you think you've got your enemy just dozing off you give the long string (which your patrol brought back) a series of spasmodic pulls. You can always judge the extent of your success by the mileage of artillery, of all weights and diameters, which your simple device sets in motion.

I can offer you another suggestion for what it is worth. About once a fortnight I send up a flare in broad daylight before breakfast, and my accomplices carry the signal along the line by doing the same at intervals. In civilian life fireworks by day serve no useful; but in war time their very incongruity and inexplicability give them a sinister air of mysterious import. To us these signals mean nothing; to the enemy they suggest, I hope, the very worst, in whatever shape their guilty minds may conceive it.

Our best effort was quite unintentional. A subaltern (whom I will not advertise by name, since goodness knows what he'd be doing next if I did) came into possession of a new kind of automatic pistol; he is always coming into possession of a new kind of something or other, and must always try it forthwith. In the absence of available targets upon which we could see the hits, he had the original idea of proceeding down the sap which runs out in front of our parapet, and shooting from there at the lonely tree in the middle of the beyond. He was followed by eight other subalterns, who were by no means prepared to admit the superiority of this pistol, for all its newness, over their own weapons in the matter of speed. I do not include in the official starters either D'Arcy or the machine-gun officer who dragged out a maxim to set the pace. D'Arcy's revolver has all the distinction of being an heirloom and all the disadvantages of capricious senility. It is at present on strike, but he refused to be left out of the competition and turned up with a hand-grenade to provide, as he said, the comic relief... It was a good start, and for sheer rapidity easily surpassed anything in this or any other war. We were so pleased with the affair from our own point of view that we forgot all about the Germans and their point of view. For a long time after it they were obviously irritable and nervy. It didn't occur to us that of course anyone would be moved by so sudden, terrific and peculiar a noise, which would have been bad enough if it had come from our parapet, but must have been intolerable when arising, as it did, from what was supposed to be the unoccupied midst of a well-known and highly-respected turnip-field.

Anything annoys them now. Even our singing God Save the King and cheering loudly, with caps raised on bayonets, on the occasion of His Majesty's birthday, raised a storm of indignation expressed in rifles, mortars and Jack Johnsons. I cannot understand their feelings; however German I was myself I should regard such a question as the enemy's own business and not mine and leave him to it and go on cleaning my rifle. And even if, having done justice to their sentiments, they next rose on their firing platform and put three rounds into me—well, I might certainly reply in kind, but I shouldn't be spiteful about it.

Let us turn from the contemplation of such dull and sordid humanity to the refreshing picture of the honest worth, if unsoldierly deportment, of my stable-boy turned sentry. Time and again I have ordered and besought him to say "Halt! Who goes there?—Advance one and be identified.—Pass, friend, all's well!" but always in vain. When the emergency arises he confines himself to what no doubt he regards as the point, and calls out shortly, "Who bist?" Only when I myself approach does he elaborate his challenge. "Who bist, Sir?" says he.

Yours ever, Henry.

Why not train our mascots to be useful as well as ornamental?

HIS ONE GRIEF.

For K. of K.

Some slight protection against hitting below the belt—the Garter.

"Sentence of three months' hard labour was passed yesterday at Bow-street on Ernest Taylor, clerk, no fixed abode, for obtaining money by fraud from Metropolitan policemen. He was arrested in the Strand by a Scottish policeman who had lent him sixpence. A detective said he was believed to have victimised 40 constables."—Daily Chronicle.

Constable (thoughtfully): "Bang went saxpence, but (with an effort) I'll no be sayin' it wasna worth it."

WAITING FOR MORE.

When I joined, the battalion was 1,500 strong. In those days I never bothered to look for a job; jobs were flung at me. "Somebody must take the company digging," said the Captain to the junior Captain; "You heard that?" said the junior Captain to the senior Subaltern; "Carry on," said the senior Subaltern to me; and for three and a half hours the company and I excavated heavily. After two months of this my health broke down so badly that I had to go before a medical board. "Nothing less than five bottles of champagne, five plays, and five little suppers," they reported, "can save this officer's valuable life." So I took five days' leave...

I came back as from another world, and reported myself to my Captain next morning in a dazed condition.

"Hallo," he said; "had a good time?"

I could hardly trust myself to tell him what a good time I had had.

"That's right. Well, somebody must take the company digging."

I saluted and went out. It was all just the same, but now I was glad of it. I wanted to forget about my five days' leave. The harder the work, the less time to think.

The Orderly-Sergeant came up to me as I reached the company lines.

"Company present, Sir," he said.

"Present where?" I asked, looking round the horizon.

"Here, Sir," he said, indicating a man next to him.

I opened and shut my eyes rapidly several times; no more men appeared. It was obviously a dream.

"Wake me up properly in an hour's time," I said, "and bring me some hot water."

"This is all the men for parade," he said patiently.

"This one one?"

"Yes, Sir."

I turned to it. "Company, stand easy," I said, "while the Sergeant explains."

The explanation was simple. Taking advantage of my absence the War Office had sent more than a thousand men to France or some such foreign place. There was only just enough left for guards, fatigues and what nots. Moreover I was now the senior Subaltern of the company.

"Well," I said, "we must carry on. What's the parade this morning? Digging?"

"Attack on a flagged position is down in orders, Sir, but it's sure to he cancelled."

"Why? Our man could hold the flag. He's just the shape for it. Well, anyhow, we'd better get down to the parade-ground. Company, slope arms. Move to the left in ones—form ones. By the centre, quick march."

I got my man down safely, none of the company falling out on the way, and stood him at ease while I considered how to display him to the best advantage. I was just maturing a clever idea for misleading the Sergeant-Major by trotting my man round and round him several times with great rapidity, when the Orderly-Sergeant came back with the news that the parade was off.

"Then so am I," I said, and I went back and reported to my Captain.

"I thought that there wouldn't be much doing," he said, "but you'd better hang about a bit in case anything turns up."

"Can't I help you at all?"

"No, thanks; not at present."

So I hung about. It was a sultry day—the sort of day when doing nothing makes you hotter than the most violent exercise. After an hour I could bear it no longer; I went back to the company room.

The Captain was just signing something.

"Blotting-paper?" he said, looking round at a junior Subaltern near him.

The junior Subaltern stretched out his hand for the blotting-paper.

"Pardon me," I said, stopping him just in time. "You have been busy all day; I have done nothing as yet. This is my work." And I handed the Captain the blotting-paper.

The junior Subaltern nearly cried.

"It isn't fair," he said. The junior Subaltern's always supposed to do all the work. As it is I haven't had anything to do for three days. At least, except yesterday. And they only let me take something across to the orderly-room yesterday because it was raining."

I looked at him eagerly.

"Say that again," I commanded. You took something across to the orderly-room—right across the square?"

"Yes. You see, it was raining hard."

"And then walked back again and reported that you'd done it? Two walks?" He nodded. "I say, I wonder if there's any chance today———"

The Captain looked up.

"I shall want somebody to take this across to the———"

The junior Subaltern was just a shade too quick for me.

"Yes, Sir," he said, snatching at it.

I followed him to the door.

"I must remind you that I am your superior officer," I said, as I got my foot against the door just in time. "Give me that paper."

"Be a sportsman," he pleaded.

"It isn't only that. What I feel is that you are too young for a job of this kind. We want a more experienced hand." I took the paper from him. "There is a particular busy way of walking across to the orderly-room which it takes weeks to acquire. You would probably stroll across as if you were going to borrow a match, and then the whole job would be wasted. Now watch this."

I strode briskly across the square, the obviously official document fluttering in my hand. A few subalterns with nothing to do watched me enviously. Outside the orderly-room door I hesitated a moment, and then turned round sharply and strode back again. The junior Subaltern, mouth open, waited for me to come up to him.

"By the way," I said, tapping the document in a business-like way, "is it Monday or three pairs?"

"Who did?" he said stupidly.

"Because, if it was Portsmouth," I went on, "it ought to have been endorsed on the back." I showed him the back, nodded to him, and hurried off to the orderly-room again. I handed in the paper and stepped briskly back to report to my Captain.

*****

"Initiative," I said to the junior Subaltern, two minutes later, as I upset the ink over the Captain's table, "initiative is what you junior officers lack so greatly (I'm extremely sorry, Sir; let me mop it up. Perhaps I'd better write these lists out again, Sir, as I've spoilt them rather). Initiative, my dear young friend," I went on, as I selected a suitable pen, "is to the subaltern on active service what-er———" I caught his eye suddenly and had pity on him. "If you're very good," I said, "you may read these names out to me."

We settled down to it.

A. A. M.

The Prismatic Blush.

"'The German Ambassador's face thereupon became suffused with all the colours of the rainbow.'

Signor Salandra concluded: 'Von Flotow was a gentleman.'"—Evening News.

Without this assurance we might have been tempted to imagine that he was a chameleon.

"Rome, Tuesday.—Great indignation is felt at a report from Barletta that the Austrian destroyer which yesterday fired on the town, hitting the castle, was flying the British gag."—Evening Times.

We wonder that the Press Bureau permitted this impudent infringement of its powers.

High-spirited Special Constable (to suspicious character). "I-if you d-don't call y-your b-brute off—I'll run you in!"

FROM A MINE-SWEEPER IN THE DARDANELLES.

(Letter from Sub-Lieut. John Blundell, R.N., to his Uncle, the Rev. J. Blundell.)

May 30, 1915.

H.M.S. ——— at Sea.

Dear Uncle,—I was very pleased to get your letter this morning and to hear that Aunt Fanny is recovering from influenza, and that Cousin Dorothy got second prize in Divinity. It was most interesting to hear that Tabs had two black kittens this time; I rather thought that they would be grey, as the last lot were white. I quite follow your arguments about "Should clergymen fight?" As you say, the matter is of the greatest importance, and naturally The Times published your letter.

You tell me that you gather from the papers that the great silent Navy is having a quiet time now, and you ask me what we are doing. I wish I knew myself, but as we only go into port once a week to coal and are not allowed to communicate with the beach, I am rather ignorant of its doings. No, I am sorry to say I did not get the wild duck. It went, as all gifts do, into the Fleet Pool, and I got a pair of mittens (my seventh pair) instead. We are the Scouts, and come last on the list. There are five grades before us. The luckiest devils are the harbour defence flotillas, who get the fruit and fish. The next best off are the Coast Defence Patrols, who get the fowls and their so-called fresh eggs. The intermediate grades, such as Grand Fleet, seagoing flotillas, etc., get the general cargo, and we, who are far from home, get the frozen mutton, the imperishable corned beef, the indestructible tinned salmon, and the endurable woollen gear. The things that we might reasonably hope to find in our class, such as grouse and gorgonzola, never pass beyond the second grade.

As our boats are not sufficient to carry all hands, the latest scheme is to keep a large barrel of grease and thick oil on the upper deck, and preparatory to abandoning ship all men are supposed to strip and smear themselves over with this stuff as a protection against cold water. They then, according to the latest Admiralty circular letter, are permitted to leave the ship. We had a false alarm the other night, hitting a floating mine, which didn't explode. A weird figure was seen hovering round the upper deck afterwards, and it took us all the middle watch to clear the oil and grease off the ship doctor.

My last skipper has been having an awfully good time in port since the Great Blockade began, as a German submarine kept on hovering about outside and they could not go to sea until it had been dealt with by the T.B.D.'s. It was known as the "Married Man's Friend," and they were quite sorry to hear of its decease. I saw Jack the other day. He is in one of the old battleships, officially termed "Fleet-Leader" (we call them "mine-crushers"), and he says his only diversion is the constant redrafting of his will so that each member of the family shall bear a fair burden of his debts.

Charlie Farrel is in the mine-sweeping brigade. He is now in his fourth trawler, and is known as "Football Charlie," as he's always being blown up. Rather bad luck on a fellow who is +2 at golf and who regards all other games (except fighting) as contemptible.

As you say in your letter, great issues are at stake, and it must be awfully exciting in England just now, but it's very dull at sea, so I will clear up this letter.

Your affectionate Nephew, John.

"Are you a millionaire, father?"

"No, my boy; I wish I was."

"How much money do you get, father?"

"Oh well—sometimes I make as much as a hundred pounds in a month."

"A hundred pounds a month!"—(slowly, after a pause) "and he gives me tuppence a week!"

MR. PUNCH APPEALS.

There is urgent and ceaseless need for more of those sand-bags which have been the means of protecting the lives of so many at the Front. Men are dying daily for need of this protection, and one can imagine no more useful work for those who want to be of practical service to our troops. No possible limit can be put to the number required. Mr. Punch earnestly hopes that his readers may be persuaded to devote some of their time and labour to this simple means of saving life. Communications should be addressed to Miss M. L. Tyler, Linden House, Highgate Road, N.W.

Those whose hearts have been moved by the gallant deeds of our Canadians in France and of our Australian and New Zealand troops in the Dardanelles will be very glad to have an opportunity of doing some little service to the brave soldiers of our Dominions who are training in England or come home to us wounded. F.-M. Lord Grenfell has just opened the Victoria League's Club for Overseas Soldiers at 16, Regent Street, Waterloo Place, and contributions will be very welcome. They should be addressed to the Hon. Treasurer of the Victoria League, at 2, Millbank House, Westminster, S.W.

Mr. Punch begs to acknowledge a donation of £5, collected by two officers at the Front on a water-wagon, for the Children's Country Holidays Fund. He has forwarded this generous gift to the Secretary of the Fund.

False Teeth in Literature.

"A Court of Inquiry will assemble at 11 A.M. to-morrow the 10th inst., to investigate upon the circumstances under which Pte. ——— lost his artificial dentures."

Battalion Orders of the —th Bn. Royal Fusiliers.

To the Munitions Department.

A FISH STORY.

(Whales sometimes attain an age of five hundred years.)

SOME BIRD.

The Returning Dove (to President Woodrow Noah). "NOTHING DOING."

The Eagle. "SAY, BOSS, WHAT'S THE MATTER WITH TRYING ME?"

ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

House of Commons, Monday, 7th of June.—Attention just now centred on Treasury Bench, where the lion of Conservatism sits down with the lamb of Liberalism, and that shrewd little child, Henry Herbert, leads them. The Member for Sark has idea that even more interesting is the figure on Front Opposition Bench of the statesman who by strange chance, after many vicissitudes, comes to represent that well-known agricultural hunting district, the Wimbledon Division of Surrey.

HENRICUS CHAPLINIUS WIMBLEDONENSIS.

"To-night the noblest Roman of them all filled his part with added gravity"

Forty-seven years ago Harry Chaplin entered the Commons as Member for Mid-Lincolnshire. Held the seat for twenty-eight years. Through period approaching half a century has watched slow changes of procedure and manner that have revolutionised the House. Whilst ever preserving the courtly manner of his early generation, has tactfully adapted himself to circumstance. For a while, between 1886 and 1900, he found himself included in any creation or reconstruction of Conservative Governments that happened to be in progress. Ministerial career terminated with last year of nineteenth century, fitly closing with its calendar. In conjectural talk about constitution of Coalition Government, roaming over probabilities and possibilities, his name was never heard.

There remains vacancy in one post unsalaried and, in the strict sense of the word, unofficial. There is no Leader of the Opposition, for sufficient reason that organised opposition is non-existent. His Majesty's Ministers still with us; for first time in Parliamentary history His Majesty's Opposition has disappeared from the scene. To man of Chaplin's constitutional principles (a matter of native instinct), this condition of affairs fraught with grave danger to the State.

Not lacking Members below Gangway on both sides self-comforted by assurance that they could add fresh influence to important position. Mr. Ginnell, for example, last week made bold but ineffective bid for it. On reflection Member for Wimbledon Division, with his long experience, his intimate acquaintance with Parliamentary men and matters, modestly but justly conscious of possessing esteem of all parties and sections of parties, came to conclusion that perhaps no one would fill the office better than himself.

Accordingly on first day of assembly of House under direction of Coalition Government he, rising from seat on Front Opposition Bench in far-away times occupied by his old friend and master Disraeli, of late in possession of Bonar Law, interposed with the question Leader of Opposition is accustomed to put to Ministers on such occasions—

"What business does the Government propose to take next week?"

Crowded House, quick to grasp the situation, genially laughed and heartily cheered.

To-night, the noblest Roman of them all filled his part with added gravity. Usual when a Minister moves Second Reading of important Bill for Leader of Opposition immediately to follow and indicate line his party is prepared to take. Chaplin, preserving the non-party but all-patriotic attitude assumed by his immediate predecessor in office, expressed the hope that the Bill would be passed without a moment's delay.

In a well-disciplined force that should have settled the matter. Leader of Opposition has, however, not yet had time to drill his men. Using phrase in Parliamentary sense, he cannot yet get them promptly to "form fours" on word of command. Their natural instinct is to break out in sixes and sevens. Thus it was tonight. Long wrangle delayed progress with a measure declared on highest authority to be urgently needed for safety of country and for protection of gallant men who by thousands daily sacrifice life and limb to preserve it.

Business done.—After acrid debate Ministry of Munitions Bill passed Second Reading without division.

Design representing the distorted views entertained by certain querulous sons of liberty as to the methods of the new Minister of Munitions.

Tuesday.—Handel Rachel Booth weeping at absence of ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer, would not be comforted. Anxiously enquired about him yesterday. This afternoon, observing his vacant seat, Handel, nothing if not musical, chanted the enquiry, "Oh where and oh where has my Celtic laddie gone?"

"My Right Hon. Friend," the Prime Minister loftily replied, "is either Minister of Munitions or he is not Minister of Munitions. If he is Minister of Munitions he is not entitled to sit here. If he is entitled to sit here he is not Minister of Munitions. As a matter of fact he is not Minister of Munitions as there is no such office until the House passes this Bill, and there is no such person."

Gibe of course unintentional. But a little rough on hardworking colleague that he should be alluded to as the Mrs. Harris of the Cabinet. Lloyd George was officially nominated to new Ministerial office. If, truly, there is "no sich a person," as Mrs. Betsey Prig asserted on historical occasion, House and country have suffered serious loss.

That stormy petrel, Arthur Markham, all over the place, pecking at everyone. Began at Question time with harmless President of Board of Trade, whom he accused of shielding an enemy firm concerned in construction of chimneys; of keeping up price of coal; and of encouraging large bluebottle flies to frequent butchers' shops.

Impression naturally conveyed that Markham was in league with small body of Radicals irresistibly inclined to dissemble their love for members of Coalition Government. Illusion happily removed when, towards end of squabble that lasted a couple of hours, he blandly alluded to "a party growing up in the House who are friends of the Germans."

Finally suggested that House should conduct debate with closed doors. General shrinkage from proposition. Sufficiently alarming to have the stormy petrel flying round in full light of criticism. What might happen if doors were locked and Press Galleries emptied fathers of families do not like to think about.

Business done.—Ministry of Munitions Bill read a Third time and sent on to Lords, who passed first stage in less than a jiffy.

Wednesday.—Making first appearance in capacity of member of new Government, Prince Arthur on rising was greeted with general cheer. He brought good news, supplementing announcement by important statement. Another German submarine has been sunk. After manner of British sailors, foreign to habit of the enemy, her crew of six officers and a score of men were rescued and brought in as prisoners.

In course of Winston's reign at the Admiralty no action of comparatively minor importance was more heartily or more unanimously applauded than his insistence that men systematically engaged in practices which Prince Arthuer to-day described as "mean, cowardly and brutal," ought not to be placed upon equality of treatment with other prisoners of war. The submarine crews were accordingly isolated in their internment. As everyone knows, the Kaiser retorted by taking thirty-nine British officers, and subjecting them to special privations, including solitary confinement.

It happened earlier to-day that Lord Robert Cecil was asked whether it would not be well in view of proposal to exchange invalid civil prisoners of war to placate Germany by reconsidering question of treatment of submarine crews.

"I think," said the new Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, "it would be a very unfortunate precedent if this House allowed itself to be blackmailed by the German Government."

Loud cheer approved this noble sentiment. Equally loud applause, twenty minutes later, greeted Prince Arthur's announcement that the alleged blackmailing had been successful. Neither demonstration was so enthusiastic as that which followed upon Winston's original statement on the subject.

A concatenation of circumstances which shows how strange and fickle a thing is public opinion.

Business done.—The Lords pass Ministry of Munitions Bill through all its stages. Commons interrupted in engrossing study of Scotch Estimates to repair to other House and hear Royal Assent given by Commission.

Thursday.—Interesting debate on increased cost of food stuffs, coal and other necessaries of life. In one of his quietly delivered, forcibly argued, lucidly expressed speeches, Runciman made it clear that Board of Trade is doing the utmost within its power to grapple with unexampled condition. Debate carried on till twenty minutes past eight, unusually late sitting for these times.

Business done.—Vote for Board of Trade and other Civil Service Estimates carried without a division.

Little Boy. "How angry the sharks must be with these German submarines—of course I mean the English sharks."

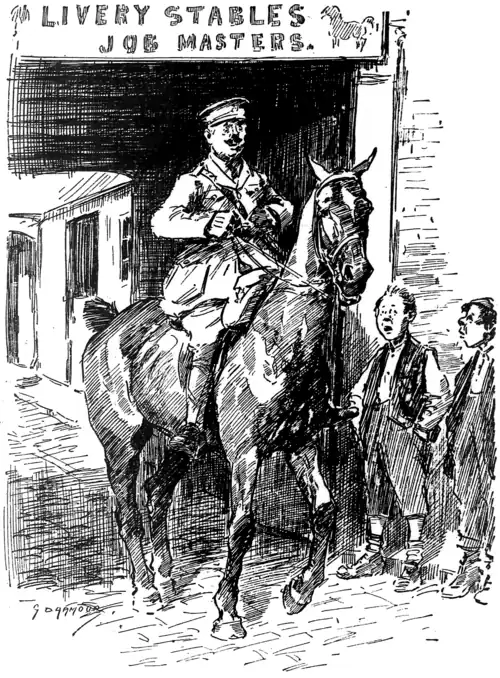

"AS OTHERS SEE US" (in uniform).

Boy (impressed by the sight of Tomkins, who has recently joined the Tooting Rough Riders Reserve Regiment). "Lor! Ain't 'e like a bloomin' Oolan?"

THE TALE OF A TONIC.

When my sister came up to town a couple of months ago she commented severely on my appearance. I was lacking in "tone" and looked ten years older than I ought to. When I demurred and observed that I was all right, and also that at my advanced age the appearance of years lent dignity, she grew annoyed. "You should take Malzwein regularly," she said. "George has been taking it for the last month and you wouldn't know him.". (George is my brother-in-law, a door-mat of a man). When I remarked that I had conscientious scruples about drinking German wines, Jane became almost angry. "'Malzwein' isn't a wine, it's a tonic made of malt and meat-juice and caseine, and recommended by the best doctors." Well, anyhow," I replied, "'Malzwein' must be of German origin, and I don't like trading with an alien enemy." "Nonsense," said Jane. "The firm is now reconstructed—I made sure of that by inquiry—all the directors are English, and the tonic is made in England. Besides, if it was a German product, and you derived advantage from it, you would be spoiling the Egyptians." I forebore to criticise the accuracy of Jane's parallel, because argument with her is generally ineffectual, and when she promised to send me a bottle I expressed my gratitude with well-simulated effusion. Two days later "Malzwein" arrived at my flat. He was a formidable-looking object in a cardboard case, with a quadrangular body and a lead-paper capsule covering his head. I placed him reverently on a shelf in my bedroom with other bottles, and having so to speak installed him in my pharmacopoeia forgot all about him until last week. It was on the night of the hottest day of the year, and I awoke at about 1.30 to be conscious of a sickly smell pervading the room.

Zeppelins—poison bombs—asphyxiating gases—such were the thoughts that crowded into my mind. But the night was still and my breathing was unaffected. I jumped out of the bed, switched on the light, and became aware of a gentle dripping sound from the shelf in the corner. And then the truth was revealed. "Malzwein" had burst, and a dark treacly substance was dripping down on to the floor. Whether it was the malt that had fermented with the heat, or the explosive energy of the caseine I cannot say, but anyhow "Malzwein's" head was blown off and he had done his best to behave like a bomb. Personally I cannot help thinking that this particularly bottle must have been made in Germany, and that it was inhabited by a malevolent imp who sought to be avenged on my indifference by at least destroying my carpet. Anyhow I am not going to take "Malzwein"—at least until I have had his remains analysed.

In a "leader" directed against compulsory military service The Daily News says:—

"In these matters we should beware of empty phrases, and we should be guided by three maxims."

Unfortunately the War Office has none of these weapons to spare.

"Bees for Sale; strong, healthy stock; only one left.—Apply, 'Gardener'"

Llandudno Advertiser.

In the circumstances the use of the plural seems hardly justified.

"As for we Londoners, who are supposed to be cowering in our holes, respirator on mouth, we are still our old dogged determined selves."

Evening Standard.

Though the respirator does interfere a little with our parts of speech.

From an Australian trade circular:—

"For Sale. Country Butchering Business Safe Southern District. Turnover, 21⁄2 bodies and 25 sheep weekly. Reliable man could be supplied wholesale, live or dead, by the vendors."

The "Safe Southern district" would appear to be situate in the Cannibal Islands.

"In various parts of South Germany earthquake hocks have been felt."—Times.

These Rhine wines have been known to have a disturbing effect upon the pavement even in this country.

MORAL GOOD.

"Francesca," I said, "would you mind———"

"You needn't say any more," she interrupted. "I know you're going to ask me to do something for you ought to do for yourself."

"Wonderful!" I said. "How do you guess these things?"

"There's no difficulty about it," she said. "You've only got to know your man."

"Is that," I said, "what is called intuition?"

"You can call it what you like," she said.

"When you guess right I shall call it intuition, but I can't do that this time."

"Well," she said, "I'm willing to bet a shilling about it."

"Francesca," I said, "when you condescend to use the language of the Turf, you may as well condescend correctly."

"I'm always a willing learner. What ought I to have said?"

"The market odds are at least two to one on. Your tremendous certainty makes them so. You will therefore offer to lay a bob to a tanner."

"And when," she said, "shall I get my bob?"

"You will not get your bob at all. I shall get your bob—that is, if you're honest."

"But where," she said, "does the tanner come in?"

"The tanner," I said, "doesn't come in at all. It remains in my pocket."

"Then I'm expected to pay you a bob and get nothing back for it. Is that what you mean?"

"Yes," I said, "that's what it amounts to. You've lost, you know."

"Then I don't wonder," she said, "that people get ruined on the Turf. But how do you know I've lost? Let's get back to the start."

"Right," I said, "let's."

"About turn!" she said. "On the left form platoon! Good gracious, where are you all?"

"We're forming two deep," I said. "Don't be angry with us. We're only volunteers, but we have our feelings, just like Kitchener's army."

"Very well then. What was it you wanted me to do?"

"When you interrupted me so roughly I was going to ask you whether you'd mind ordering some safety-razor blades for me from the hairdresser's."

"There," she said, "I knew it. Didn't I say you were going to ask me to do something for you which you ought to do for yourself."

"Remember," I said, "it's war-time."

"What's that got to do with it?"

"You mustn't be selfish in war-time," I said. "You must keep on doing things for other people, and the less you like doing the things the better it is for you. I'm really giving you a tremendous chance."

"I admit that," she said reflectively, "but I don't see how you're to get any good out of it."

"I shan't have any beard and whisker to worry me. My chin and cheeks will be as smooth as vellum."

"Yes," she said, "that'll be very jolly for you; but you won't be doing things you don't like doing for other people."

"Doesn't that sound a trifle mixed?" I said.

"Never mind the mixture," she said. "You know what I mean."

"Do I?"

"Yes," she said, "you do. You won't be getting any moral good out of it; and that is a thought I can't bear."

"Don't let it weigh on you," I said. I'm quite willing to sacrifice myself. And, anyhow, my moral good can wait till you've got yours."

"No," she said, "I can't see it in that way. I should be taking an unfair advantage of you."

46 Take it," I said; "I don't mind."

"Generous-hearted man! But try to imagine yourself after I've ordered your safety-blades. Won't there be a galling sense of inferiority?"

"What of that?" I said. "You'll step into your proper place, and that will be sufficient reward for me."

"No," she said, "if I'm to rise in the moral scale by ordering your safety-blades, I must invent something to raise you to the same height at the same time."

"That's very noble of you; but I think you'd better begin, and we can talk about my elevation afterwards."

"You shall be elevated simultaneously or not at all. I'll go to the telephone and order the blades, while you walk round to the linen-draper's and buy me a packet of assorted needles and half-a-dozen reels of cotton."

"But," I said, "I don't know the draper. He's a newcomer in the neighbourhood."

"He beats the hairdresser by a week or two."

"Besides, what good am I at needles and reels of cotton?"

"Am I," she said, "profoundly versed in the blades of safety-razors?"

"I shall buy you the wrong kind of needles and cotton."

"And I shall order you the wrong kind of blades. Won't it be fun?"

"You may think it fun at first," I said, "but what'll you say when I've got hair half an inch long on my face?"

"I shan't mind," she said. "I can pierce through the outer shell to the beauty within."

"It's a silly thing to ask a man to do," I said. "I haven't the vaguest idea what needles cost."

"The draper will tell you. He's a most obliging man."

"Mayn't I order them on the telephone?"

"No," she said, "I'm going to use that for the hairdresser. And the point of the whole thing is that we should both get our moral good at the same moment."

"I shall make a mess of it," I said.

"Not you. You'll have a glorious success, and you'll want to be buying needles for ever afterwards."

"All right," I said, "I resign myself. I'm off to the draper's."

"I'll give you three minutes' start," she said, "and then I'll call up the hairdresser."

R. C. L.

Messrs. Longmans announce the publication of a theological work entitled Was Wycliffe a Negligent Pluralist? We understand that this will be shortly followed by a series of similar volumes, of which the following are already promised:—Was Confucius a Dissolute Supralapsarian? Was Socrates an Absent-minded Archimandrite? Was Marcus Aurelius a Petulant Anabaptist.

"June the Fifteenth is Waterloo Day and as in 1815 so also in 1915 will England be engaged in oue of the Great Battles of the World. The coming of War found us unready. Our Fathers had not sufficiently kept alive the lesson of Waterloo. We, of this generation, will not easily forget the lessons of Mons and Ypres. But we have already forgotten, if we let pass the unique occasion of June the Fifteenth without using it as a means to the education of those who are to follow us."—Advt. of the Medici Society, Ltd.

Medici, heal yourselves. We shall wait for the eighteenth, as usual.

"An English lady, whose husband is much away, wishes another as companion for walks."—Glasgow Citizen.

A good chance for a "walking gentleman."

COVER FOR SHIRKERS.

It is daily requiring more and more courage for the man of military age not in uniform to be seen enjoying outdoor pleasures.

AT THE PLAY.

"Marie-Odile."

The Novice. "Are you really a man? You know, if you don't mind my saying so, you're just a little bit like one of those waxworks."

Sister St. Marie-Odile Miss Marie Löhr.

A Corporal Mr. Basil Gill.

It would be easy enough to be indelicate about the rather embarrassing theme of Mr. Knoblauch's play; for (in crude terms) we have here the tale of a little nunnery-novice who accepts at sight the advances of the first alien enemy that comes her way, and bears him a "war-baby." But the author disarms criticism by his transparent idealisation of innocence. For you are to understand that this novice has been brought up in cloistered ignorance of sexual facts; that she has never even set eyes upon a man on the right side of senility; that she is left alone in her convent, the sisterhood having fled at the enemy's approach; and that the first soldier who breaks in upon her solitude is himself virginal, and bears so strong a likeness (thanks in part to a brown-red wig which did not go very happily with Mr. Basil Gill's head) to St. Michael in the nunnery fresco that she at once identifies him with that archangel. So well is her innocence sustained that it serenely survives the relations into which they enter; nor could I even find that the "miracle" of her child's birth was ever associated in her mind with those relations. This of course means that we are asked to believe a good deal, though not perhaps an absolute breach of natural laws.

Mr. Knoblauch may have been influenced by memories of Reinhardt's Miracle or Davidson's Ballad of a Nun, but he has gone his own way. He has not taken the obvious course of approving the revolt of natural instinct against the hot-house atmosphere of the convent; he simply shows us a type so childlike that it is incapable of taint.

Perhaps any lover, not too boisterous, might have served the author's purpose passably well; but he makes sure of his ground. His soldier, though he loves and rides away (to the grave disappointment of some of the audience he failed to return and "make an honest woman" of the novice—having died, I hope, in action), is no common corporal of Dragoons, but goes far, by his attitude, to justify the child's error in mistaking him for St. Michael. My only complaint is that, having arranged these conditions, quite arbitrarily exceptional, the author should have taken occasion to pronounce, through the medium of the only enlightened nun in the establishment, a tirade against the stuffy secretiveness of the conventual system. To assign this sort of blame is to suggest (which he never intended to do) that the innocence which he has all along been glorifying was largely a mere matter of ignorance.

Miss Marie Löhr, a charming figure in her novice's dress, was the best possible choice for this virginal type. In the Second Act, when she treats the intruding soldiers like a lot of nice large dogs, she was delightful in her naïve simplicity. But the last Act dragged heavily, and I grew very tired of Sister St. Marie-Odile's enthusiasm over her "little one" in the cradle (an enthusiasm which I was not in a position to endorse, as the infant was concealed from me) and her reiterated protest that she "could not yet understand" the very natural indignation of the Mother Superior. Mr. Knoblauch might have made more of this lady if he had allowed her a touch of humanity, but here he went the way of least resistance, and Miss Helen Haye followed him with a great and cat-like fidelity. Mr. Basil Gill had a difficult task in combining the personalities of St. Michael and a seducer of innocence, but he achieved it with such discretion as the case permitted. Mr. O. B. Clarence as Peter, the sole male attached to the convent, made a lovable dotard. Mr. Hubert Carter, most robust and swarthy, showed a rough good-nature very admirable in the leader of a licentious soldiery. Among the inarticulate characters the convent pigeons did well, including St. Francis, the brown one, who was condemned to death for the Mother Superior's dinner, and never knew how large a part he played in the issue of the drama.

When I have added that the scene was too pleasant for any need of change I hope I have done my duty by a play that is not likely, for all its good qualities and still better intentions, to repeat with us in London the success it won in America at a time when they could still treat the subject of War in a spirit of detachment.

O. S.

"Gamblers All."

Sir George Langworthy, stockbroker, had a holy horror of gambling in every form—his own business, which he described as "legitimate speculation," of course excepted. That being so, it was unfortunate that he should have selected as step-mother to his grown-up son and daughter a young lady with a congenital passion for play. For a time the new Lady Langworthy managed to conceal her proclivity under the guise of an absorption in music, and ascribed to concerts the time she spent at the bridge-table. But a run of bad luck proved her undoing. She dared not tell her husband what she owed and why she owed it. Her brother, Harold Tempest, had the same fitful fever running through his veins and was already deeply in debt to one Amos, a money-lender. In despair, and on the off-chance that her luck would change, she went off to a fashionable gambling hell, kept by Major and Mrs. Stocks (admirably played by Mr. Lyston Lyle and Miss Frances Wetherall). Here she met John Leighton, a mysterious financial acquaintance of her husband, who vainly endeavoured to dissuade her from playing and offered to lend her the money; and here, too, came Sir George to fetch his wife from the "musical evening" which he supposed to be in progress. He had barely discovered his mistake when in marched the police and arrested the whole party, himself included.

The Third Act takes place at the Langworthys' on Christmas Day. In spite of her pleading Sir George refuses to forgive his errant spouse, and goes off to church in a most un-Christian state of mind. Harold appears to reveal the fact that to get money from old Amos to pay his sister's debts he has put Leighton's name on the back of a bill, and that the forgery cannot be concealed, as he has since learned—what the experienced playgoer has guessed for some time—that Leighton and Amos are one and the same. And no sooner has he gone than in walks Leighton himself to make hot love to the forlorn little gambler and to urge her to fly with him. In the last Act Leighton is visited in succession by all the principal characters. Ruth Langworthy (Sir George's daughter) tells him of her love for Harold; Sir George seeks his advice as to the recovery of his wife's affections; and Harold comes to confess the forgery. At last Lady Langworthy arrives, a pathetic little figure in white, ready to surrender herself to save her brother, though she admits that her love still remains with her husband. By this time, one suspects, Leighton is heartily tired of the whole family. At any rate he refuses the sacrifice, packs Lady Langworthy off with Sir George, and is last seen lighting Harold's cigarette with the forged bill.

The play, though a little old-fashioned both in plot and presentment, is well worth seeing, if only for the admirable acting. Leighton, a sort of Robin Hood among money-lenders, is not an easy character to make convincing, but Mr. Lewis Waller goes as near success as is possible, and in his scenes with Lady Langworthy maintains his reputation as one of the best lovers on our stage. Miss Madge Titheradge, who seems to advance with every part she plays, has done nothing better than her Lady Langworthy, whose naughtiness never overcomes her charm. As the husband Mr. Charles V. France makes us believe that the anti-gambling stockbroker is not only possible but probable; while the comparatively small part of Harold, with which Mr. du Maurier contents himself, fits him like a glove. The minor characters are all adequately filled, and a special word of praise is due to Miss Agnes Glynne's performance as a tempestuous flapper.

L.

WARNING TO HOUSEHOLDERS.

If you must take your anti-gas respirator to bed with you, you might mention it to your wife first.

"Mr. Lloyd George announces the withdrawal of beer and wine duties, and the prohibition of the sale of spirits to those under three years of age."—Ceylon Sportsman.

This part of the late Chancellor of the Exchequer's policy had hitherto escaped notice, even the persons directly affected having raised no articulate protest.

"Here the party was courteously received by Miss Broach, secretary to the Rev. Canon Rawnsley (who, owing to absence, was unable to be present)."—Manchester City News.

Nothing else would have kept him away."

"The press are specially reminded that no statement whatever must be published dealing with the places in the neighbourhood of London reached by aircraft, or the curse supposed to be taken by them."—Aberdeen Free Press.

But for the Censor's warning we should have hazarded the suggestion that it was G——— S——— E———.

"The War Office has issued respirators to all the staff of the Press Bureau."

Evening Standard.

The rest of the world can now breathe more freely.

By custom a half-quartern loaf is understood to weigh 21lbs., and purchasers who require a loaf weighing 21lbs. should ask for a 21lb. loaf."—Cambridge Weekly News.

Of course they should also see that they get it.

From a notice of Marie-Odile:—

"The theme is a very frail one, and honestly Mr. Kuolsland has not the skill or delicacy to save it...

What Mr. Knolslanch knows of nuns would go into a very small compass."

Evening News.

In the circumstances it is just as well that Mr. Knoblauch wrote the play, and not either of these other gentlemen.

Artful device resorted to by a German sniper who thought he was observed.

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

I am not quite sure that we haven't had enough of white-hot War-books. All that can be said without further, and as yet unavailable, evidence as to the causes of the Great Tragedy has been said by many competent men, and perhaps in fewer, though certainly not more eloquent, words than by Sir Gilbert Parker in The World in the Crucible (Murray). And yet I think these forceful vigorous pages will find many readers and drive home some terrible convictions. Our new baronet's method of select quotation from adversaries is open to the objection attaching to all work of the sort, that it raises a certain kind of doubt in the fair-minded reader. No doubt one might find some German book composed exclusively of hot-headed and very yellow utterances by Englishmen, arranged as a complete justification of this "Preventive War," or proving guilty machinations on the part of Albion the always perfidious. The best part of the book is the summary of German war crime, from the beginning of August last to the sinking of the Falaba; and the significant reminder of the fine chivalry with which Japan and Russia conducted their desperate struggle in the opening years of the century. Said the Japanese officers to Sir Ian Hamilton when he congratulated them on the conduct of their men: "We cannot afford to have any people connected with this army plundering or illtreating the inhabitants of the countries we traverse." While of the Russians he wrote: "The Muscovites haven't lifted so much as an egg, even during the demoralisation of a defeat." That is the answer to those sensitives who sit apart and murmur, "All war is terrible," with the implication that the kind waged by Germans is no worse than the others. It simply isn't true, and because it isn't true there are old and stodgy merchants who have never done anything more adventurous than miss the 9.45 up-train, yet, if there were any talk of premature peace, would be clamouring to be sent across the Channel in protest to the death.

I think I ought to warn you against prejudging The House of Many Mirrors (Stanley Paul) by the picture on the cover. The pale man with staring eyes who is holding up a lamp depicts indeed the hero of the tale, but the actual circumstances are not so melodramatic and creepy as their presentation suggests. Indeed, though there is drama, and grim drama, in Miss Violet Hunt's latest story, it is not of the sensational kind. It is a story of a woman's self-sacrifice, and as such has done much to strengthen me in a previous conviction that self-sacrifice can be one of the most terrible forms of selfishness. Consider the facts. Rosamond Pleydell, a woman of the idle, not quite well-enough-to-do set, loved her husband, whom she supported out of her own income. The husband was one as one of several possible heirs to an old uncle, but was supposed to have lost his chance by marrying Rosamond, the betting being strongly in favour of Emily, a female cousin, who had been sent to look after the old man—in more senses than one. Rosamond, finding herself stricken with mortal disease, and knowing her death would leave the man she loves without his little comforts, conceals her state, and, having persuaded him into a protracted visit of ingratiation to the will-maker, herself goes off abroad to die alone. She even prepares a batch of cheery letters, to be sent at regular intervals before and after her death, in order to keep the husband from deserting his task. Naturally when, having got the inheritance (and incidentally complicated matters by falling in love with Emily), he finds out the truth, he suffers as any woman who cared for him could surely have foreseen. My admiration for Miss Hunt's real cleverness of style made me sorry that she has wasted it here—and not for the first time—upon a sordid tale of unpleasant people.

Tares (Chapman and Hall) is the name that Mr. E. Temple Thurston has given to a collection of short stories and sketches. To save you from a wholly unjustifiable misapprehension, I should perhaps explain that the title is simply taken from that of the first story in the book, and has no reference to the general character of the whole. "Tares" itself is a very well made and poignant little sketch of certain events in Malines, centred in the historic and terrible pronouncement made from the pulpit by a priest of that town. Both here and elsewhere in this book Mr. Temple Thurston has shown himself able to write about the War with passion and yet with dignity and restraint. A rare gift. There are other sketches, semi-satiric studies of the female character divine, which are of more unequal merit. Some of them, to be honest, hardly seem quite to have earned their place. The best of the humorous batch is the last, a story told with delightful humour of an engaging idiot named Cuthbertson, who thought he could box and was tempted into a Surreyside ring—with disastrous consequences. I liked especially the touch which depicts him, confronted with the peculiar aroma of the dressing-room, and observing that it was "a bit niffy"; though, as the author points out, "this was not his usual method of speech. He was doing as the Romans do in Rome." Perhaps Mr. Thurston won't thank me for saying that I place some of the contents of this modest volume much above his better known novels. But I do

A selection of the verses which have appeared on the second page of Punch during the War has been published by Messrs. Constable at 1s. under the title War-Time.

More Commercial Candour.

Draper's notice in the middle of a sale week:—

"I have no guarantee that these blouses will last till Saturday."