Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3846

CHARIVARIA.

If proof were needed that Turkey knows that she will have to quit Europe very shortly, it is to be found in the we presume if port that she is now offering territorial concessions to Bulgaria.

⁂

A telegram from Panama states that the crews of two barques sunk by the Prinz Eitel Friedrich in the Pacific were landed on Easter Island and abandoned. This procedure is quite "correct." All the best pirates used to go in for marooning.

⁂

Among the new summer fabrics is a cotton material known as "Joffre"; and we hear that a muslin which is very easily seen through is to have the sobriquet of "Bernstorff."

⁂

Says the Vorwärts:—"Loud are the complaints among the Berlin population about the quantity of sand which they are finding in tho municipal potato supply. For these complaints there seems to be but too much ground." "Too much ground" is distinctly good.

⁂

"Fleet Street," said The Daily News recently, "was all agog yesterday with the news that a Sunday newspaper was to be published next Sunday." One can even better imagine the excitement there would have been if its publication had been announced for a Monday!

⁂

Owing to the scarcity of male labour many women, it is said, are learning to become drivers of motor-vans. Some of them are taking it up so thoroughly that they are reported to be also receiving lessons in the art of repartee and other forms of road-language useful in case of collisions.

⁂

The fish market is said to be suffering from the prevalence of submarines; and patriotic fish are invited to migrate to our rivers, where, they may be caught in comfort.

⁂

In a shop window, the other day, we came across a card on which were exhibited a number of "Patriotic Buttons." All must surely be well with the nation when even its buttons are so loyal.

⁂

Sir Laurence Gomme, on his retirement as Clerk to the London County Council, has been appointed honorary adviser to the Council on antiquarian matters. The tramway system will, we presume, now come within his purview.

⁂

The Alhambra Theatre recently offered a prize for the best name for its new Revue. This appeal to the great public for help would seem to have been justified. The witty title, "5064 Gerrard," has been adopted.

Mr. Charles Gulliver is presenting at the Palladium a new Revue entitled "Passing Events." That he has not called it "Gulliver's Travails" does credit to his modesty.

⁂

It is announced that on and after the 29th inst. the B———y* Tower at the Tower of London will be open to the public. [*Excision by Censor Morum.]

Importunate Pedlar (who has had door slammed in his face). "Gawd punish 26!"

Agoraphobia.

"Wide streets, says a fashion writer, do not look as extraordinary as we have been led to expect."—Evening News.

Still, we do not care for them in the dark shades which are in vogue at the present time.

"Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep."

"A.B. Seaman George ———, of H. M. S. Zulu, had a brief furlough last week end at his father's home. His ship has been on patrol duty, and he had slept in his hammock since August, a proof of the ever watchfulness our Navy."—Lancaster Guardians.

In accordance with the traditions of the Service, George of course slept all that time with one eye open.

Having sprinkled our entrenched soldiers in the West with flaming petrol, the Germans are now, according to a Petrograd report, squirting boiling pitch over our Russian allies. Another instance of the Kaiser's well-known piety: "Let us spray."

Letter from a gunner, printed in The Evening News:—

"We get plenty of food, including fresh meat, coal, oil, tea, sugur, milk. cheese, bread, butter, jam (bacon every other day), and rum."

On the strength of the above statement the Kaiser will doubtless redouble his efforts to break through the British lines, knowing that our gunners are, on their own confession, now fed up with "firing."

The Cleveland Plain Dealer (Ohio) tells us of the invention of a bullet whose head has a cavity for holding phosphorus. It is designed for dealing with Zeppelins. But its utility would seem to go further than that. "When the rifle is fired," says The Cleveland Plain Dealer (Ohio), "the bosphorus is ignited by the discharge." We commend it for use in the Constantinople campaign.

Western Morning News.

We do not like the word "flattening." It suggests the Steam Roller, a term of endearment to which our Allies have objected.

Saskatoon Phœnix.

According to the other Phœnix, the proper way is to roast the hens.

Western Morning News.

Reply received (on a postcard)—"Why not kill Germans instead?"

TO ENGLISH GENTLEMEN AT HOME.

RAISING THE WIND.

There is little doubt that our Recruiting Band has done yeoman service at our Thursday evening Recruiting Campaigns, and it would do even better if it only possessed a bass tuba. We have lots of bandsmen who play top and middle music, hut only one (a euphonium) who plays ground-floor music. This is scarcely surprising when you come to think that low notes are much more expensive to produce than high ones. You can buy a very good cornet for two pounds, but in order to produce exactly the same notes as the cornet a few feet lower you have to invest in a bass tuba that may cost you six times as much.

All this was admirably explained by Mr. Fogge (the bandmaster), who one evening, when the Overture to William Tell had been rendered without any bass at all (owing to the indisposition of the euphonium), mounted the plinth of the drinking-fountain round which our campaign rages, and asked "our public-spirited fellow-townsmen" for more practical support for the band. In a powerful of peroration he pointed out the increasing need for a bass tuba, and pleaded with a possible philanthropist in the crowd to earn his country's undying gratitude by supplying the deficiency.

Unfortunately, in the report of the proceedings which appeared in The Poppleton Argus, "tuba" was spelt "tuber," with the result that the Vicar, who goes in for market-gardening on an extended scale, sent to the band's headquarters the largest potato he could find.

This was literally the only fruit of Mr. Fogge's stirring appeal, and finally it devolved on me (I am only the hon. treasurer of the band, not an executant) to devise some other means of obtaining the money. To accept the offer of our senior curate to lecture on John Bunyan would, I felt sure, merely defeat my object. Happily I saw in The Times what I considered to be a highly novel and ingenious method of making an appeal for charity. I therefore despatched to the office of The Argus the following paragraph: "Will every 'Huggins' in Poppleton join together to provide an urgently required instrument for our Recruiting Band? Write, etc., etc."

This, I thought, would be sure to attract the necessary money, as Huggins is the name in Poppleton, just as Rees or Jenkins is in Swansea. Judge, then, of my annoyance when, on opening the paper, I found that the wretched printer had made any advertisement read, "Will every Juggins, etc., etc." I need scarcely say that the result was nil; though one dear old lady (who apologised for her name being Brigginshaw and not Juggins), having misinterpreted my appeal, forwarded me a Surgical Aid letter. My failure was all the more galling since there was a similar notice in the paper asking all the "Jemimas" of the neighbourhood to subscribe towards the purchase of cigars for all our Tommies who didn't like cigarettes. The notion was obviously not so novel as I had imagined it. Anyhow, I subsequently learned that the "Jemima" money subscribed would have been sufficient to buy a bass tuba, a tenor trombone and the best part of a French horn. I wanted to try again by addressing my appeal to all the "Williams" and "Johns," but Mr. Fogge said, No; all the Williams and Johns had already been bled for Christmas crackers for the Canadians. He said we didn't want a bass tuba as badly as all that.

Then one day a bright idea struck me. I devised another appeal, and took it down by hand myself to the office of The Argus. To ensure its being correctly printed I offered them double rates to be allowed to see a proof of it. They told me such a course was not usual. I told them that their mistakes were also somewhat out of the ordinary, and I eventually got my way. The appeal was worded:―"Will all our townsfolk who are relatives (however distant) of, or connected by marriage (however remotely) with, persons of rank or title, contribute to a fund now being raised to provide our Recruiting Band with a much needed bass tuba? A list of all subscribers, together with the names of their relatives or connections, will be duly published in these columns. Write, etc., etc."

The success of my appeal was instantaneous. We could have bought a large proportion of the London Symphony Orchestra with the proceeds. Not only did we purchase the biggest, bassest, most sonorous tuba that money could command, but we had sufficient funds in hand to engage the services of a tubaist to play it―a desideratum that had previously been overlooked. We are now doing great business with our band, and I do not hesitate to say that if Lord Kitchener succeeds in getting all the recruits he wants it will largely due to the generosity of 89 of his second cousins thrice removed, 57 connexions-by-marriage of Sir John French, and 142 step-nephews-in-law of His local Grace the Duke of Podmore and Lumpton.

The Punishment Fits the Crime.

"Cross-examined, he said he had been caned before for reading thrashy literature."

"The Earl of Crewe wrote:-'Is this' (racing)' or is it not conducive to the prosecution of the war to a successful end? If it is, it is desirable; if it is not, it is undesirable. If it is neither, from the public standpoint it is immaterial.'"―Daily Telegraph.

Either Lord Crewe wrote this or he did not. If he did, he should read our book on the Included Middle; if he did not write it, he should demand an apology. If he neither did nor didn't―well, it is immaterial.

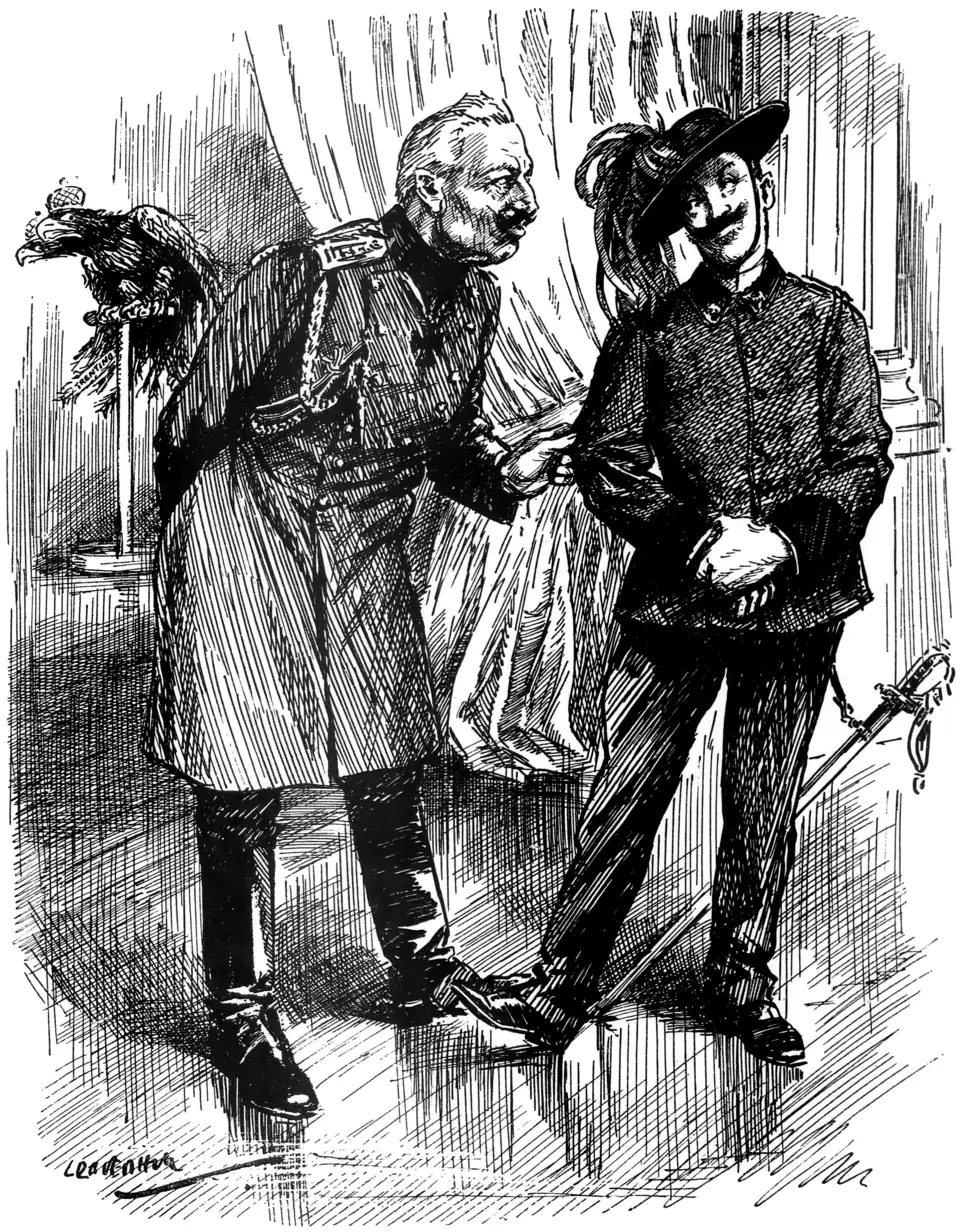

VICARIOUS GENEROSITY.

Kaiser. "SHOULD YOU WANT SOME MORE FEATHERS, I KNOW A TWO-HEADED EAGLE."

Child (to gardener in Kensington Gardens, mending the cotton cross-threads over the crocus blooms). "Would you please tell me―are those threads to keep the Zeppelins off?"

A MORAL SCOOP.

["The day when news was the thing seems to be passing; papers now vie one with the other with free insurance and advertisement schemes; thousand-pound prizes for photography and vegetables... almost everything except the news."

The Newspaper World.]

By its existing insurance scheme, its war-poetry contest, and its generously endowed laundry competition, The Daily Boom already shows its solicitude for life and limb and its interest in the æsthetic and industrial pursuits of the people. By way of a change it launches to-day a mammoth prize offer of immense moral significance.

The Daily Boom has long felt that it might perhaps take some part in the encouragement of moral effort among all classes, irrespective of creed, party, position, taste or any other distinction. The management has therefore promulgated this new and amazing competition.

Every person anxious to add to his finances by improving his character should enter to-day, his first step being to hand a written order to his usual newsagent for the regular delivery of The Daily Boom at his house.

A sum of £50,000 (Fifty Thousand Pounds) has been set aside by The Daily Boom, from which substantial money prizes will be distributed among certified regular readers for:―

(1) The finest personal moral deed of the week.

(2) The noblest personal moral achievement of the (calendar) month.

(3) The most glorious personal moral triumph of the half-year ending on Michaelmas Day.

This is the most colossal inducement to the formation of noble character that the world has ever known.

In this competition the Editor's decision is final, whatever it may be in regard to political programmes and other matters.

Whether it be the servant-girl who tells of her free and uninvited confession to breaking the best teapot, or the clergyman who, under the stimulus of our offer, preaches his own sermon after all, and tells us the story of just what happens, all should compete.

Keep that five and four noughts in mind, and go out and do something noble so that you may become a competitor to-day. As you go do not forget to leave a written order with your newsagent; otherwise your efforts will be wasted.

Rewards will also be given to the street newsvendors who supply the lucky prize-winners. Each will receive one clean collar and a packet of voice jujubes per week for life.

Enter now (not forgetting that written order) and do your country good.

What the Censor saw.

Extract from sailor's letter to his wife (fact):—

"Dear Jane,―I am sending you a postal order for 10s., which I hope you may get―but you may not―as this letter has to pass the Censor."

"A look-out must always be kept by the men in the trenches. Even while the photographer was busy one kept observation."

Daily Sketch.

After all, War is War―even in face of the Kodak's undeniable claims.

Study of a Patriotic Gentleman in his Home Turkish Bath―of course bought before the War.

THE WATCH DOGS.

XIII.

Dear Charles,―Agréez, M'sicur, mes what-d'-you-call-'ems, and have the goodness to believe that your old watch dog has broken loose from his kennel, swum the English Channel, and is now pushing along in cattle trucks or on his flat feet towards the dog-fight proper. Up to now we have heard no more of it than the barking of very distant guns, but by the time you read this we hope to be getting our own first bite. I may say now that I think we should have had some difficulty in keeping our pack in order had it not been for this move to the area of more serious activities.

Our first performance upon landing in France was to whistle "The Maseillaise," an act of friendship and courtesy long premeditated in the ranks. This created a deep impression, but mostly among ourselves. In fact all of us were a little disappointed at the lack of enthusiasm upon our arrival; we had expected the inhabitants to turn out en masse (or bloc) and shout themselves hoarse at the sight of us. Two facts had, however, escaped our anticipation; the first, that the hour would be 7 A.M., an early time for wild enthusiasm; the second, that we should not be the first to arrive by some hundreds of thousands.

Our military ardour was not the only thing about us to be damped on that morning. There was a light drizzle, also sent from heaven to make us realise from the start that this outing is not a picnic; and when eventually we reached our temporary canvas home and nestled down as best we might amongst the mud, there were not a few of us who felt that there was, after all, something to be said for the dull but comfortable round of home life. From what I have seen already, I doubt if the domestic side of war has ever before been so well catered for, but even so it is distinguishable from a pure beano. It has, however, its lighter side, as for instance when I go shopping in the villages for the officers' mess. One has to have read with deep concentration to be able to remember at the pinch how to demand a dish-cloth in an intelligible fashion. We feed almost entirely off pork chops at the moment, owing to my personal tendency to crack my little jest with the village butchers. For when I have done with business my butchers and I turn to discuss the friendship of the Allies and the detestability of the foe. It is always, "À bas le Kaiser!" from me; "C'est un cochon," from them, and the rejoinder from myself "Ça me gere un peu d'acheter des côtelletes de cochon." And so that no butcher in France may miss this jeu de mot, my unhappy mess must continue eating pork chops till we have settled down.

I started composing this letter in a first-class carriage. I continued it in a lonely tent, writing upon a biscuit box. again in a cattle truck, again in an expansive château, deserted by its owner but furnished splendidly with every modern convenience. I conclude in the sole tap-room of a not unthirsty village. The room is fifteen feet square; it is at once the local bar, the battalion headquarters, the mess and the bedroom of half-a-dozen officers, including myself. And when you consider further that le patron and his family of five also inhabit it you may imagine that at times it is almost congested. But for the competence of Madame his wife I think we should not long survive. M'sieur stands always in the middle of the room contemplating the complex situation with an expression of inscrutable gloom. By the stove, upon which the meals of all of us are cooked, sits permanently the pallid eldest son, who is said to be an invalid but is really a wastrel. He is there when I go to sleep; he is there when I wake up. But I have my suspicions that he moves about a little in the meanwhile, when there is no one awake to be interested in his maladies. The younger son is as bright a lad as you could wish to meet. He smokes a pipe (with some inner reluctance, I think), swears in English, and has innumerable boon companions among the early-rising labourers of the place. I woke up this morning to find a couple of them sitting on the end of my valise and me, drinking their first cup of café. By the time I was thoroughly roused the whole family were at their several posts in various corners of the room. It was essential for me to rise and shave myself; it was also essential for la patronne to cook upon the stove. But "toujours la politesse," and the worst may be passed off with a jest, so as I lay upon the floor and Madame bustled about I conversed affably with her, starting with her business, proceeding to the general excellence of her cooking, suggesting dishes most worth eating, specifying pork chops in particular, and ending triumphantly with the cochon jest. After that an atmosphere was created in which anything might be done without offence.

Meanwhile, always in the distance (now the nearer distance) is the booming of the guns. I suppose the trenches are about a dozen miles away and that we may be in them at any time now. Well, we are all ready for it and are asking no questions. For my part, however, I cannot help wondering inwardly how it is that men can keep on killing each other in this methodical and deliberate fashion. Nobody is in a hurry; nobody is in the least excited, and I am quite sure that if there was a picture palace in the place we should all crowd into it for the sake of distraction. Châteaux or tap-rooms, battles or marketing, one takes it, apparently, as it comes, trusting that Mr. Asquith or someone has his eye on the progress of events. However, by the next time I write I hope I'll have something more moving to write about; but I doubt it, Charles, I doubt it. We shall have got there all right, but I am beginning to suspect that even when we do we shall find nothing but a turnip field and a deep ditch in which shall stay till we are told to come out. There'll be a noise, of course; but what good will that be? Nobody will be able to look over the top and see what the noise is all about. None the less I will tell you the facts as soon as I get news of them.

Yours ever, Henry.

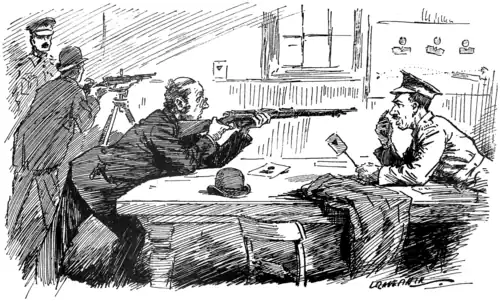

Veteran (receiving instruction in the art of aiming). "I was always told as a boy, you know, never to point a gun at anyone."

THE AWAKENING.

Until last Tuesday I am certain Aunt Priscilla did not realise the War. Realise it as an actual awful thing, I mean.

But war and all that it means has at last been brought right home to her, and this is how it came about.

The pale cheeks of Jenson the parlour-maid began it; the recommendation of Winoria, the restorative wine, as a remedy directly contributed towards it, and the conscientious zeal of Snooks the grocer completed the great awakening. It was in this wise.

Jenson, as I say, was pale and out of sorts, a condition unlikely to escape my Aunt's all-seeing eye, and someone had suggested Winoria. Why not? Aunt Priscilla decided at once for this invigorating wine-tonic. The very thing.

Abroad early, Aunt herself swept into the establishment of Mr. Snooks and ordered a bottle of Winoria, with a request that it should be sent to Everest Place without delay.

"I regret, Madam, that we have no cart or cycle available at the moment; this afternoon..."

"Impossible. I must have it before lunch. Give it to me and I will myself convey it home."

The suave manner of the shopman instantly changed to a wary caution. With an uneasy glance at the clock he said firmly: "I regret, Madam, that we cannot serve women with intoxicants before eleven!"

Aunt Priscilla! But of course you don't know my Aunt Priscilla.

A TEMPORARY SUSPENSION.

Extract from a Soldier's letter:―

"Dear Sister,―I send you these few lines hoping they find you as this leaves me at present. I have a bullet wound in the hand."

Warning to Mariners.

"A titre de première réponse à l'Allemagne, l'amirauté anglaise a pris une mesure de restriction concernant la navigation aux deux entrées de la mer d'Irlande. Les navires désirant traverser le canal du Nord devront passer au Sud-Ouest et à quatre mille au plus de l'Ile de Rathlin, entre Sunrise et Sunset."

XXe. Siècle, Havre.

Unfortunately these famous headlands are rarely visible in our foggy atmosphere.

For a "Château en Espagne."

Extract from a land company's circular―

"The 'Sunnyside Estate' is beautifully situated, high up in the air, fronting good roads, along which water-mains run and is bounded by a very pretty avenue of trees."

Just the place for a retired aviator.

From the tape:—

"Enver Pasha has sent in the name of the Sultan the Grand Military Meal for Merit to Admiral von Tirpitz and Gen. Falkenhayn."

This was tactful of Enver. The gift will in present circumstances be much more appreciated than a tawdry decoration.

From an article on "Jobbing Gardeners":―

"One has to know their man before we can trust him to work in our gardens."

Amateur Gardening.

Quite so; and they will have to learn our grammar before one can be let loose among his flowers of speech.

SENTRY-GO.

The whole idea of posting sentries was ridiculous. Just because we had borrowed part of a man's country house and called it a week-end camp there was no real reason for turning three men out in the cold night and calling them sentries.

The first I heard of the business was a casual remark from our section-commander that I "was on two to four." I took this to be some silly attempt at a racing joke, so I said, "What price the field? " just to show that I know the language; and I thought no more about it until I ran across Bailey. The same cryptic remark had been conveyed into Bailey's car, but he had discovered the solution, though I don't believe he guessed it all by himself. The fact was that wo had been picked with Holroyd to do sentry-go between 2 A.M. and 4 A.M. Personally I felt that the responsibility was too great, so I went in search of the section-commander. I told him what my doctor had said about the risk of exposing myself to the night air and pointed out the absurdity of posting sentries against a non-existent enemy, He wouldn't discuss the matter at length, and I suspect that he had heard some of the arguments before, though not so ably put.

Of course I didn't get any sleep before 2 A.M. This was partly due to the want of "give" in the floor, partly to the undue preference shown by Bailey's foot for my left ear, and partly to the necessity of stopping the tendency of certain members of the company to snore. Some injustice was done in the last process, as it was difficult to locate the offenders.

As I thought it might be wet I borrowed Higgs's overcoat and rifle. I hate getting my own overcoat soaked through, and I never was any good at cleaning rusty rifles.

It was a thoroughly dirty night, and I took up my position under a tree, leaving the others the easier task of guarding open ground. Owing to the discomfort of sitting in a puddle I never got properly asleep, and this accounts for the fact that my attention was attracted by a slight noise in my vicinity. I diagnosed a cat, dog or snake, all of which animals can be found in that neighbourhood. As I dislike things crawling about me at night-time I picked up a serviceable-looking brick and hurled it in the direction indicated. Naturally I didn't expect to draw a prize first shot, and was surprised and much gratified to hear a groan and the sound as of a body falling. I had evidently brought down a German spy and eagerly rushed forward to retrieve my game. It was a man right enough, and I found him quite easily. I found him with my feet and lost my initial advantage. However, my luck was in, and in the ensuing rough and tumble I came out on top. When Bailey and Holroyd arrived in response to my shouts I was well astride his shoulders and had his face concealed in the mud.

They both seemed a little jealous at my success and, when they heard the details, began to suggest that I had acted irregularly. Bailey, who is a special constable in his spare time, said I ought to have warned the man that "anything he said would be used in evidence against him." Holroyd said that I ought to have waited until he shot me before taking action, and then gone through some formula about "Halt, friend, and give the countersign." As they seemed to think they could still put the matter in order I appointed them my agents and gave them an opportunity to say their pieces.

Bailey retired two paces and solemnly delivered his warning. He got it off quite well, and I admit that it sounded impressive. Holroyd wasn't quite sure of his part, and Bailey tried to look it up in his "Manual" while Holroyd struck matches. Holroyd burnt his fingers three times while Bailey was trying to find the place, so he had to say it from memory after all. Holroyd presented arms and said, "Halt. Who goes there? Advance, friend, two paces, and give the countersign. Welcome." We thought he had gone wrong on the word "Welcome," but it sounded a courteous and harmless thing to say under the circumstances, so we let it pass.

The man, whose face was still firmly embedded in the mud, didn't do any of the things Holroyd told him. I put a little extra pressure on the back of his head to make sure ho didn't say "Friend," and he had no real chance with the countersign as we hadn't fixed on one.

Everything being now in order we sent Holroyd to fetch the picket. Holroyd had some trouble over the picket, as they had forgotten to elect one and no one volunteered. Ho got very unpopular through having to wake up so many people to arrange about it.

In the meantime I caught cramp from sitting so long in the same position and allowed Bailey to relieve me. When the picket arrived they didn't get much fun out of the captive, because Bailey had spoilt him for the purposes of resistance by getting more of his weight than was necessary on the man's head. The picket had to carry him up to the house and pour quite a lot of brandy into him before he showed any signs of life. They got him breathing at last and told off a fatigue party to clear some of his mud. They hadn't properly got down to his skin when his power of speech revived. There seemed something familiar in his voice in spite of the fact that it was muffled by about a quarter-of-an-inch of mud, and it occurred to me that I had better resume my sentry duty without delay. I didn't all anyone's attention to my departure because I wasn't sure that I ought to have left my post. I took Bailey's military book and someone else's electric torch.

My remaining hour passed quite quickly and I was almost sorry to be relieved. When I got in I heard that our Commandant was up and wanted see me. I found him in a dressing-gown sitting in an armchair. He wasn't looking very fit and had a nasty gash over the right eye. As he's in the regular army and only lent to us I waited for him to start the conversation. He seemed to find some difficulty in getting off the mark, but on the whole performed very creditably for an invalid. I didn't attempt to answer half the questions he asked. He didn't seem to expect it―they don't in the army. I just said, "I was on sentry-go, Sir, at 2.35 A.M. when I heard a suspicious person. Being on active service at night I dispensed with the challenge and should have fired if any cartridges had been served out. Under the circumstances I did the best I could with the material to hand. I was fortunate in capturing the intruder and handed him over to the picket. I've not yet heard whether he has been identified. "

He wasn't quite himself, and I fancy my answer surprised him. He seemed to have a piece of mud in his throat, and before he could get it clear I had saluted and got away. Bailey's military book is quite a useful little thing.

I was astir early in the morning and took a walk in the direction of the post-office. Before eleven o'clock I had received a telegram calling me to town on urgent family affairs. I had got an idea that that part of the country would have proved unhealthy for me. My personal view of the whole matter is that our Commandant might have known that we should be awake at our posts without getting up in the middle of the night to find out.

We learn from America that General von Bernhardi has joined the staff of the Press Bureau and by Imperial permission has given his exclusive services to a well-known New York paper. The Kaiser is now assured of a place in the Sun.

Outraged Artist (about to paint important military subject). "You pig! You've eaten the khaki!"

[It is reported that a small German outpost, occupying an isolated house amidst the floods of Flanders, is always warned of night attacks by the quacking of ducks. The following lines are alleged to have been written, for British consumption, by a German prisoner.]

MILITARY QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS.

[The Advice Column on Military Matters, now a special feature of many contemporaries, must not be supposed to belong only to the present day. That similar columns were in vogue in other times is proved by the following extracts from antique records.]

J.Cæsar (Rome).―By all means write an account of your experiences at the Front, but take care to find a striking title. The one you suggest, "The Gallic War," is very flat. Why not: "In the Neck, or How we gave it to the Gauls?"

Attila (Hungary).―Quite so, but are not your methods a little boisterous? What will the Germans think of you?

Joan (Arc).―Certainly not. If, however, you feel that you must be doing something military, is there no local body of girl guides which you could join?

Francis D. (Plymouth Hoe).―It is all very well for you to play games in war-time―quite picturesque and so forth, but does it not occur to you that in future days, when perhaps conditions will be more stringent, your example may be quoted by persons not wholly inspired by disinterested motives, who have reasons (financial and otherwise) undreamed of by you for continuing sports?

Horatio N.―See an oculist. We must tell you frankly, however, that the loss of the eye finally closes your naval career. You should think of taking up some civilian employment.

Wellesley (Eton).―We should be in a better position for offering you advice as to your chance of success in a military career if we knew more of your achievements on your school playing-fields.

Napoleon B. (Corsica).―Your height would tell against your chances, and we should that for other reasons as well you are hardly cut out for a soldier. Have your thought of the counter? If there is not much opening in your neighbourhood, you might think about coming to England, where, as you doubless know, there are plenty of shopkeepers.

"Girl wanted to take care of quiet baby, who is fond of singing ragtime―Chinatown, etc."―Montreal Star.

A precocious infant, but surely a little old-fashioned.

MORE PEOPLE WE SHOULD LIKE TO SEE INTERNED.

"Well, we'll bring the car to-morrow, and take some of your patients for a drive. And, by-the-by, Nurse, you might look out some with bandages that show―the last party might not have been wounded at all, as far as anybody in the streets could see."

THE NORTH SEA GROUND.

CLUB CHANGES.

Drastic Economies.

At the Plutomobile Club it has been decided to import 500 Peruvian waiters. At a general meeting of the Club held last week a motion was passed by a small majority permitting the smoking of pipes after 12 P.M. and sanctioning the introduction of 6d. cigars. We understand that the performances of the Blue Bessarabian Band in the great porcelain swimming bath have been temporarily suspended.

A remarkable innovation is to be introduced at the Lantern Lectures which are so welcome a feature at the Benedicks' Club. It has been resolved to accept the offer of several distressed dowager peeresses to serve tea without wages, the "tips" being left to the discretion of the members.

The tariff of the Caviare Club has recently undergone substantial alterations. The price of the house-dinner is now reduced to 15s. a head and champagne is no longer de rigueur. On the other hand an attempt to sanction the introduction of barley-water and cocoa nibs has been heavily defeated.

Visitors to the National Democratic Club cannot fail to notice the altered appearance of that famous caravanserai. The marble walls and staircases have all been whitewashed to discourage ostentation and promote moral uplift.

ENGLAND'S IDEAL IN WAR-TIME?

[The Jockey Club's decision to continue racing has been very well received in bookmaker circles.]

HOW HISTORY ANTICIPATES ITSELF.

Sister Sophie sewing shirts for Nessus.

ONE OF OUR CANDID FRIENDS.

[In The Boston News Bureau, a daily paper, Rear Admiral Francis Tiffany Bowles, formerly Chief Constructor of the American Navy, who has recently travelled throughout Germany, has stated his belief that Germany will win. He adds: "The probable situation is that all the Allies are now ready to quit, and that means not only France and Russia but England; that Germany is ready to make peace with Russia and France, but never with England. The possible consequences of such a situation areecasily discernible, and merit the most serious consideration by the people of the United States. The chance of a successful invasion of England cannot be lightly dismissed."]

Comforts for the Troops.

"Madame Tussaud's Exhibition.―Beautifully illuminated. Well warmed and Ventilated Heroes of the War."

Advt. in "The Times."

"It is quite feasible that more than one submarine has the same number. The result of this would be that an exaggerated idea of the possibilities of the under-water craft would be gained, since, for instance, the U 21 may be seen in the English Channel one day and in the English Channel almost immediately afterwards, or even at about the same time."

Liverpool Echo.

Even without this duplicity the feat does not appear insuperably difficult.

Has anyone seen our Provost?

"Help for Gallant Little Serbia

Flag Day, Glasgow, Saturday, 27th March.Under the patronage of the Rt. Hon. the Lost Provost and Magistrates of Glasgow."

Glasgow Daily Record.

"The only object of Prince von Buelow's remarks is to make the Italian Government believe that there still remains a possibility of diplomatic your-parlers being satisfactory."

Glasgow News.

Prince von Bülow. Will my walk into my parlour?

Signor Salandra. Thank you, wo have had quite enough of your-parlers.

From a Daily News' description of "a town in France":―

"LUXURIES AS USUAL.

The fool supply is for all essential purposes unaffected."

It is the same with the German supply of Court jesters.

"At Findon on Wednesday morning the Grand National Candidate, Irish Mail, cantered a mile twice, and will probably do a good gallon on Thursday."

Gloucester Citizen.

This sounds like "doping," but perhaps Irish Mail is training for a "pint to pint."

Visitor. "Is it a boy or a girl?"

Patriotic Mother. "Oh, a boy, Miss. We don't want girls nowadays, and doctor says everybody's having boys."

THE SUSIE GAME.

"Oh, Mr. Meyer," said my hostess, 'you are so clever, you must think of a new game for us."

If there is any form of request more paralysing than this, I should like to hear of it. So clever! To be called so clever in a company containing several strangers, and then to have to prove it! Surely tact should be taught at schools, although, of course, after logarithms.

By some bewildering miracle an idea suddenly entered my head. "Why not play at 'Sister Susie'?" I said.

"You don't mean more sewing?" my hostess replied in dismay.

"No, no," I explained, seeing daylight as I talked. "First we want twenty-six little bits of paper. Will someone tear them up? Then on these we write the letters of the alphabet. Then they are put in a hat and shaken up, and we take out one each in turn. As there are twelve of us we shall have two each, and two of us will have three each, to make the twenty-six. Is that all clear?'

They said it was as clear as mud, and I went through it again with the crystal clarity of a teacher of one of those advertised systems which impart a perfect knowledge of French in three lessons.

"Then," I said, "you take a sheet of paper and fill up a line for each of your two (or it may be three) letters, in the manner of the famous Sister Susie line, which I am told is sung wherever the sun never sets:―

That is to say," I added, "that supposing you had A you might write―

or if B:―

It must be alliterative; it must be as much in the metre of the Sister Susie line as possible; and it must have reference to the War."

The company having intimated that this also was as clear as mud, I repeated it.

"But what about X?" a pretty girl asked.

"Yes, and Z?" asked someone else.

"And Y?" asked a third.

"I felt sure there would be some defects in the game," I replied. "We are only feeling our way, you see. We had better leave them out."

"Oh no," said Aunt Eliza; let's try them."

Aunt Eliza spends quite half of her life in guessing acrostics and anagrams, and the difficulties of writing-games are food and drink to her.

Then the inevitable happened.

"Oh, but I can't play this," said one guest who had just begun to grasp its character.

"I'm sure I can't," said another.

"I'm hopelessly stupid."

"You must leave us out," they said.

Ten minutes having passed in fighting to retain them, during which time a third and fourth took courage and fell out too, we settled down to the hat with only eight players. That is to say, we were each to have three letters, and Aunt Eliza and I, being the most gifted, were to share X and Z.

We were just beginning when the pretty girl wanted to know how we were to manage about relationships. "'Sister Susie' is all right," she said, "and 'Auntie Alice' and 'Cousin Connie,' but there aren't any more; unless we say 'Father Freddy' and 'Mother Molly,' and 'Brother Bertie' and 'Uncle Ulrich.'"

It was therefore decided to cut out relationships and begin with the girls' names right away.

And so we started, five minutes being allowed. I saw at once that Z was useless. Zoe and Zuleika could be found easily enough, but there was nothing to set them to do. I therefore concentrated on my other letters, which were U and J, and with infinite agonies produced:―

and

Our hostess came out strong with C:―

and G was very passable:―

Y was ingenious but not of the best:―

I need hardly say that Aunt Eliza played it best. Aunts always do play this kind of game best. Her three letters were P, S and X. The first two she rendered thus:"―

and

"But what about X?" we demanded.

"X isn't really possible," she said. "Xantippe is the only name, and there are no verbs for her.

is all I can do."

Perhaps other players will get better results.

Feasting the Eyes.

"The view of the Euxine from the heights of Terapia, just seen through the end of the Straits, is like grazing upon eternity."

Devon and Exeter Gazette.

In the Elysian Fields, we presume.

"Dr. Macnamara, in reply, stated that there had been no case of tetanus at Osborne and no epidemic, but only isolated cases of the form of conjunctivitis, alluded to Lord Charles as 'pink eye,' during the last two years."―Isle of Wight Evening News.

This regrettable personality, continued over so long a period, should surely by this time have reached the ears of the Speaker.

Labouring Man (sorrowfully). "Wot if I do owe yer a tanner―wot's a tanner? 'Ere's me thinking in millions―millions o' pahns to 'elp keep the old country safe―and there's you grahsin' abaht a measly―paltry―bloomin' little tanner! Where's yer patriotism?"

COPPER.

Dear Mr. Punch,―Having been fortunate enough to put your readers right on the question of Germany's War strength―one notices that there has been a cessation of newspaper bickering on the subject since my letter appeared―I propose to-day to deal with the burning question of the supply of Copper. We shall take horses next, of course, and after that rubber and petrol, and (if there is still no important movement in the West and the space must be filled) we may also have to treat of cotton before we are done.

Copper is a subject that I have completely at my finger ends. I need not say that it is of vital importance. When Germany's copper is done the War must end. And first let me point out, as no one else has done, a signal instance of German foresight, yet another proof that every detail of this adventure had been considered in advance. I refer to the institution of the Iron Cross. Let us suppose that Wilhelm in a weak moment of vanity had preferred what would have been much more effective―a Copper Cross. Think what a dilemma would have faced him now. Either from lack of ammunition or from want of decoration the contest must have come to an inglorious end.

What is Germany's expenditure of ammunition? East and West she holds a line of, let us say, 800 miles. This line is occupied by some 4,000,000 first-line troops. (We are counting in the Austrians here, for, though they may not always wait to pop it off, after all each one of them does carry a rifle.) This works out, in Flanders, at about 5,000 men to the mile, in Poland at about 3,333 men to the verst, and in France at about 2,999 men to the kilometre. I speak of course in general terms. Shall we say three men to the yard? Making all the usual allowances we may call it 21⁄2 men to the yard. Keeping well within the mark let us admit only 2 men to the yard. Jealously avoiding extravagance, put it down at 11⁄2 men. Reckoning conservatively, call it one.

Well, now, what is the number of shots per rifle per man (or per yard) per day? Frankly, we shall have to make a guess at that. It might be simply anything. Naturally it all depends. But (omitting a series of rather abstruse calculations―in working yards into poods―which may be seen by anyone who cares to call at the office) we cannot be far wrong if we bring it out at 290 tons a day, for rifle fire, of copper alone. Adding 10 per cent. for maxim fire―though there is no special reason why we should select that particular figure―we get about 320 tons. But we must remember at this point that a good deal depends on the pitch. Nothing can be made out of mud, but on hard frozen ground rifle bullets may bounce and be recovered, provided that the enemy does not interfere. We must allow for that.

Now let us throw in shells. What about 200,000 a day? Let us say 150,000. That comes obviously to 309 tons 2 cwt. and a trifle. Near enough. Unburst shells of the enemy may also be gathered up sometimes, if you wait a bit. We must allow for that.

{{c|Conclusion.

We have now been led step by step to the solid fact―and there is no use blinking it―that Germany will need exactly 217,000 tons of copper per annum for ammunition alone. Of her sources of supply it may be said with absolute certitude

(1) That her present imports from neutral countries are unknown.

(2) That her own production cannot be quite exactly estimated.

(3) That no one has the least idea what her stocks were before the war.

Much depends upon what she can gather up in the way of copper wire and odds and ends. And here it must be borne in mind that any tampering with the telegraph wires may interfere with the Imperial correspondence, without which war cannot be waged. But there are other sources. And here we come to the most striking instance of lack of preparation―the one important detail where German foresight failed. It is a point that no other commentator seems to have touched upon, although it is in truth the root of the whole matter. Germany alone of all the leading belligerents is without a copper currency. She cannot turn her pennies into shot and shell. We shall not be far wrong in assuming that this deficiency will be the final turning-point. The General Staff may if it will collect all manner of cooking utensils; the time may come, under the pressure of British sea power, when they will not be of much use, any way, with nothing to cook in them. They may commandeer electric-light fittings; they cannot thereby keep the people any more in the dark than they are already. But they will be baulked and thwarted if they look to retrieve their fortunes by an assault on the National Reservoir of the pfennig-in-the-slot machine.

I am, Sir,

Yours, as before, Statistician.

BÊTES NOIRES.

A Postscript.

"Of course," writes a correspondent, "everyone has his own bêtes noires, as you said in last week's number, and one man's black beast may be another man's white angel. This matter can be settled only by personal opinion, and yet I have a feeling that there is a set of persons whom all must equally place on the noiriest list; I mean the people who talk clever to their dogs in public." We agree.

Extract from the latest War Office Drill Book as given recently by a N.C.O.:―

"Should a Mule break down in the shafts it should be replaced by an intelligent Non-Commissioned Officer."

THE SABBATH CAMERA

THE TALE THAT TOOK THE WRONG TURNING.

(A Magazine Study.)

Gerald Arbuthnot took his seat in the train with a frown of impatience. He had, of course, other things as well, such as a return-ticket, the usual quantity of luggage, and a copy of a journal that modesty forbids us further to specify―but the frown was the significant item. How irritating it was, he thought, to be obliged to make this journey! Still more vexing were the provisions of the preposterous will that had rendered it necessary.

Gerald was a bachelor, tall, wealthy, handsome and of the usual age. It is hardly worth while for me to describe him, since you have met so often before, and will meet as often again, in the pages of contemporaries. Still, there he was―for the artist to do his worst with. To his impatience the train seemed a long while in starting. At last, however, all was ready, doors banged, whistles blew, the platform began slowly to recede past the windows...

Gerald, a little surprised, but undoubtedly relieved, settled himself comfortably in his corner. He was to enjoy the journey undisturbed. And then, just when it seemed too late, the thing happened which Gerald and you and every reader with experience had been looking out for. The door was flung open and the figure of a young girl, exquisitely, if indefinitely, clad, was thrust into the compartment.

It was the heroine.

"Here we are again," said poor Gerald wearily, but not aloud; for if he was one thing more than another it was well-mannered. "Up or down?" he asked, after a sufficient interval to allow the girl to settle herself into the opposite seat.

"I beg your pardon?" You know the voice in which she would answer, sweet yet cold―like ice-cream.

"I mean," explained Gerald, "that as some sort of dialogue is obviously expected of us we might as well begin about the window as about anything else."

She melted ever so little at this. "Possibly," she said; "but why not wait till the accident?"

"I'm afraid I don't quite understand. What accident?"

The bewilderment in Gerald's face was too apparent not to be genuine. At sight of it the last trace of chill in the girl's manner vanished utterly; as a short-story heroine she was naturally trained for speed in these matters. "Why," she said, with a little gasp of incredulity, "surely you know that I am here for you to rescue me in the railway accident?"

"It's―it's the first I've heard of it," stammered Gerald.

"But you must," persisted the girl, beginning now to be a little confused in her turn. "See, round my neck I have here the locket which falls open as you lay me unconscious upon the embankment." She unfastened it eagerly as she spoke, displaying the portrait of a young man like a cheap wax-work. "My brother" she said. "But of course you think I'm engaged to him, and you go away, and we don't meet again till long paragraphs, perhaps even pages, have rolled by."

There was a moment's rather embarrassed pause. Then she added shyly, "It―it all comes right in the end, though."

Gerald's colour matched her own. In black-and-white illustration you would have to take this for granted. But no illustrator could have made him look more foolish than was now the case.

"Believe me," he said, "no one could more sincerely regret the fact than I do. But there has obviously been some mistake."

"Mistake? I don't understand you.'

"What I mean is," said Gerald, "all this accident business. Of course, as a private individual I should at any time be delighted to rescue you from anything in reason. But as a hero, accidents are (if you will forgive me) not in my line."

"Your line?" cried the astonished girl.

"Light comedy," he explained, "with sparkling dialogue, and perhaps a touch of refined farce. At the present moment I am travelling into the country to meet an unknown heiress whom my late uncle's will constrains me to marry. So naturally when I saw you come in———"

"I see," said the girl. "It was an error," she added magnanimously, "that any hero might excusably make."

She looked so attractive in her own rather vague line-and-wash style as she said it that Gerald was moved to continue―

"I only wish it had been true."

The girl suddenly laughed, perhaps to cover her slight confusion.

"I was thinking," she explained, that, as two short stories are apparently laid in the same train and have got mixed, in some other compartment there is probably a strong silent hero who specializes in rescues trying to make head or tail of your bright comedy heiress."

"Suppose," suggested Gerald suddenly, "that we leave them at it."

"How do you mean?"

"There's a station in five minutes. Let us slip out thore, and leave them to explain matters to each other after the smash. That ending would be at least as satisfactory as the usual kind."

The train was already slowing down. "Will you?" he asked.

Still, though the paragraphs were running out, the girl hesitated. Then at last she turned to him with that wonderful smile of hers that has been the grave of so many artistic reputations.

"Yes," she said. She held out her arms.

"My mistake!" said Gerald apologetically; "I had nearly forgotten that little formality."

He kissed her.

Voice from the far-end of hut (to Sergeant, who is retiring after expressing himself strongly on the question of "lights out"). "Sergeant! Sergeant! You haven't kissed me good-night!"

Fine Head-work.

{{blockquote| "The advance of the Allied Fleet up the Dardanelles is causing the heads of the Balkan States to stroke their chins thoughtfully."

Southern Daily Echo.

A Debt of Honour.

The Hon. Secretary of the Committee for the Relief of Belgian Soldiers writes to the Editor of Punch:―"M. Emile Vandervelde, Minister of State, would be very grateful if you would again help him, as the need of the Belgian Soldiers is very great, and as the earlier appeal which you were good enough to publish was very successful." Mr. Punch begs his kind readers to send further assistance to King Albert's gallant Army, addressing their gifts to M. Emile Vandervelde, Victoria Hotel, Northumberland Avenue, W.C.

"He is again near the scene of his defeat at the said Przanyss."―The Observer.

This is mere swank. Mr. Garvin has only written it; he never said it.

"The second of the Saturday afternoon lectures at Trinity College will take place to-morrow afternoon at half past three in the Convocation Hall, when Dr. Alexander Fraser will lecture on 'The Kiltie Church in Scotland and Its Missionary Work.'"

Toronto Daily News.

Is this the Church more widely known as the "Wee Frees," many members of which are doing excellent missionary work in Flanders in counteracting Kultur?

THE UNIFORM.

"So you've got it on," said Francesca, as she surprised me before the looking-glass in my dressing-room.

"Yes," I said, "I've got most of it on. There are a few straps I'm not sure about, but we can fit them in later."

"You'll never get those straps right," said Francesca; "there are too many of them. No civilian could possibly cope with them."

"But when I wear this uniform," I said, "I'm not a civilian. I'm a soldier, every inch of me."

"But you can't be said to wear the uniform properly until you've got it on, straps and all, so if you can't put on the straps you'll be a civilian to the last day of your miserable life."

"Things might go better," I said, "if you'd come and help a chap instead of splitting straws at him. This Sam Browne belt will be the death of me."

"Don't give in," said Francesca, "and don't get so suffused. An officer in a Volunteer Defence Corps should be more determined and less purple in the face. Infirm of purpose, give me the leather."

"Take it," I said, "and do the best you can. I'm fed up with all these brass rings and studs and buckles."

"I wonder," said Francesca, as she took stray shots with the strap-ends―"I wonder if Sam Browne, the inventor, can ever have dreamed of the agony his belt would some day cause to a thoroughly inoffensive family. There―the belt is safely on, the straps are all tucked up tight into something or other. You look fairly like the illustrated advertisements. Now let's study you at a distance."

"Not yet, Francesca. I haven't got my sword on yet. I refuse to be inspected without my sword."

"One sword forward! Quick! Isn't it a beauty? Which side ought it to go?"

"There is a prejudice in favour of the left side, and you'll find a place specially provided for it there."

She jammed it in and stood off to coutemplate the effect.

"Of course," I said, "a sword is a superfluity. They don't really wear swords now-a-days at the Front."

"But you," she said, "are really wearing this one, and that's all I care about. Why, the hilt alone is worth all the money."

"Yes," I said, "the hilt is extraordinarily handsome."

"It's the most bloodthirsty and terrifying thing I've ever seen. But tell me, now that you've got the whole uniform on, what are you?"

"I am," I said proudly, "a Platoon Commander or a Commander of something of that kind. They won't let me call myself a Lieutenant for fear of my getting mixed up with the regular army, but I'm a subaltern all right."

"A grey-haired subaltern," she said, "one of the most pathetic things in literature. Don't you remember him in the old military novels? A most deserving man, but so poor that he could never rise in rank. The gilded popinjays turned into Captains and Majors and Colonels, but he, although he kept on winning battles and saving the army, remained a subaltern to the end. I never thought to have married a grey-haired subaltern."

"Well, you've done it," I said, "and you can't get out of it now. Another time you'll be more careful."

"Let's go out," she said, "and take a walk through the village and show you off."

"But I don't want to be shown off," I said. "This uniform is meant for work, not for show."

"And do you mean seriously to tell me," she said, "that, after bruising my fingers on your straps and rings and buckles and Sam Browne belts, I'm to get nothing out of it, not even a little innocent open-air amusement? Come, you can't mean that."

"Yes, I can. I'm not ready for the open-air yet. The uniform's not accustomed to it."

"But," she said, "you must begin some time or other."

"I know I must; but I shall do the thing gradually, so as to coax the uniform into the air. One day I shall stand in the lower passage, where there's always a draught, and the next I can open all the doors and windows in the library and walk about there, and then by the end of a week or so I might work out into the porch, and so, bit by bit, into the garden. But it'll be a slow business, I'm afraid."

"Volunteer uniforms," said Francesca, seem to take a lot of hardening."

"They do," I said; "and besides there's another objection going out."

"What's that? Your modesty?"

"No," I said, "my pride. We might met a regular soldier."

"We should be sure," she said, "to meet dozens of them, and they'd all salute you. I should love to see them doing it."

"But suppose they didn't do it, where would you be then, Francesca, and how would you feel about your grey-haired soldier boy? These regulars might fail to realise the importance of my grey-green volunteer uniform or even to recognise its existence. Such things have happened."

"But Tommy Atkins is a hero, and no hero could be so cruel as that."

"Oh yes, he could," I said. "It wouldn't cost him a thought. All he would have to do would be to look straight at me and not to raise his hand to his cap. It's the easiest thing in the world."

"Then you're afraid?" she said.

"No," I said, "I'm not. I feel as if I could face fifty Germans, but just at present I'm not going to chance it with Tommy Atkins."

"You're the most disappointing Platoonist I ever knew," she said. "But perhaps you won't mind my calling the children. There's no reason why they shouldn't see their father, the Field Marshal."

"Yes," I said, "you may call in the children."

R. C. L.

THE PIG-IRON IN THEIR SOUL.

[Dr. Pannewitz, in an article in the Berliner Tageblatt, advocates the slaughter of 20,000,000 pigs, in order to preserve the potato supply, remarking that they are more dangerous than the English army, etc., put together.]

Bill (who has just acquired a trench periscope). "Here y'are, Alf. Now you watch me. This is how to get 'em."

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Peter Paragon, Mr. John Palmer's novel, which finds itself in Martin Secker's intriguing Spring list, is a version of the old Odyssey of youth in search of love. Unlike our latest fashionable heroes, who arrive at their approximate solutions through successive experiments of varying degrees of seriousness, Peter, a thoroughly serious person from his earliest years, steers clear of rocks of temptation and shoals of false emotion, finally bringing his unwrecked galley safe into harbour. So much distinctly to the good. But here's a curious book. On page 60, Peter's father, conscientious clerk, admirable gardener, ineffectual anarchist, whose relations with his son are quite charmingly described and realised, is brought home dead from a street meeting with a bullet through his brain. Some serious effect of so unusual a happening is no doubt intended? Not at all. It simply marks the end of a chapter and the beginning of others in a quite new key. Peter, made rich by a successful uncle, goes up to Oxford, to Gamaliel, becomes inevitably "Peter Pagger," and leads a set of intellectuals who sharpen their wit by elaborate ragging. An old Gamaliel man may be assumed to speak with authority, as here he certainly does with sprightliness, of several of the traditional rags of recent years, adding in a burst of creative exuberance the diverting adventure of the trousers of the Junior Prior. Peter, sent down, and established in London, wearies of the intellectuals of Golder's Green and Clement's Inn, and drifts reverently into upper circles. Here, to be candid, his creator slips into something perilously near The Family Herald, tempered of course by the Gamaliel manner. No, the part about the dying Earl, and Lady Mary, who believed so immensely in herself and her order, won't do. And if the other parts about the naughty granddaughter of the farmer, and Vivette, the musical comedian, and the return of Miranda will do (of which I'm not sure), at least they don't fit. In fact I'm not quite convinced that Mr. Palmer has not been indulging in a little literary rag of his own for our confusion.

Probably by this time most readers of memoirs have pleasant associations with the name of Mrs. Hugh Fraser, so that her latest volume, More Italian Yesterdays (Hutchinson), will need little recommendation. If you love Italy and enjoy anecdotal history, ancient and modern, served in a medium of pleasant gossipy talk, you will like this book. Much of it might perhaps more aptly be described as Italian days-before-yesterday. There are, for example, some chapters on the sanguinary affairs of mediæval Naples, and others―more interesting―about the rise and fall of King Murat. For these last alone the book would be well worth reading. But what I have always liked most about Mrs. Hugh Fraser's style is its versatility. Discursive is an inadequate word. She is fully capable of ranging in a paragraph from the horrors of Bourbon cruelty to the engaging naughtiness of her nephews. As she herself says, "With the best intentions in the world I start to tell the story of some great person... and in the middle of the tale the sun strikes on my page―a child laughs across the street... and farewell to the historic train of thought! My hero or saint recedes into the shadows, and relinquishes the canvas to a thousand amiable little sprites of memory who hold it till they have frisked through the very last step of their dance." Which exactly, and far better than I could do it myself, indicates the charm of her book. I loved especially a story she tells―in connection with nothing―of how her small sister and brother sent out widespread invitations for a party of "theatrakulls" to the number of some two hundred, and only by a happy accident was the grown-up hostess warned of this entertainment. It seems characteristic that no attempt was made to avoid the undesigned responsibility, and the "theatrakulls" duly took place, with enormous success. Surely, much of the jollity of a family like that survives in its daughter's pages.

There is, or was, to be seen in the papers an advertisement of some profit-sharing tobacco company, of which the chief feature was a happy-looking person with a cigar in his mouth who was supposed to be saying through the clouds of the same, "I am paid to smoke." I achieved something of this man's happiness while reading The Voice of the Turtle. The thought that I was actually being paid to read it made my pleasure perfect, for as a rule, when I become absorbed in a book, an inconvenient conscience worries me with suggestions that I am a lazy devil well on the road to the workhouse. It is a shame to take money for reading The Voice of the Turtle. It is the pleasantest, most engaging book. Shallows, Mr. Frederick Watson's last novel, good as it was, had not prepared me for this excellent comedy. If Messrs. Methuen, who publish both books, have any influence with Mr. Watson, they will urge him to stick to comedy, for it is his line. He has the style, the sureness of touch, the gift for characterization, the humour and the instinct for the good phrase which command success in this branch (or twig) of literature. He can be delightfully amusing, and, like the lady in Mr. George Ade's fable, can "turn right around and be serious." As proof of the first statement I would adduce the description of Mr. Martin Floss's reasons for taking Deeping Hall, in Loamshire, his journey thither and his first attendance at church; as proof of the second, the various scenes in which the gradual alteration in his character is conveyed to the reader. Mr. Watson, as a writer, is the exact opposite of his Mr. Richards, the choir-singer. The latter, "with a reckless debauch of strength," produced no results whatever. The former has written an excellent novel without seeming to exert himself at all. He has just quietly thrown off a little masterpiece.

Mrs. Parry Truscott had intended to call her latest story Such Is Life, but discovered at the last minute that this title had been already requisitioned. She has hit on a second name that is meant, I suppose, to come to about the same thing as the first, since to be Brother-in-Law to Potts (Wener Laurie), or such as Potts, may be taken as a typical incident of every-day existence. For it is as a very ordinary person that he is introduced, and the same applies to his brother-in-law; in fact so humdrum did all my new acquaintances seem likely to be from the opening chapters that I had serious doubts whether I could ever call them friends. A fellowship in tube and bus is all very well, but on a winter evening I like the figures that people my hearthstone to bring in some finer air of mystery and romance. But the authoress, as I ought to have remembered, knew well what she was about, and showed me once more that the slangy bank clerk on the opposite seat was not only her hero, but a worthy knight of King Arthur's Table; that her commercial traveller carried about a lifework of regeneration with his bag. Indeed before I had gone far I was made to realise that, though the scene of the drama was a London common and a house or two in its dreary neighbourhood, the piece itself, humorous, romantic, tragic in turns, was really an old, old mystery play―consciously allegorical. Whether as an allegory it is entirely successful, or whether it will be remembered more for the fascinating intimacy of its characterisation and the almost uncanny penetration of its philosophy, I am not presuming to say. Perhaps you may think that the difficulty of knowing where to stop is not perfectly overcome―I admit I would rather have known either more or less of the Beautiful Lady―but that is a point you must consider after reading the book. Take my advice and do so at once.

Glad as I am to welcome Mr. Eden Phillpotts back to the Devonshire that is his by right of pen, I think that Brunel's Tower (Heinemann) is a little lacking in salt and also in West Country atmosphere. But it would be unfair to blame Mr. Phillpotts for these regrettable omissions because his main object here is to give us a very complex psychological study. "A tall, thin boy was stealing turnips, and, chance sending a man to look over a gate, that accident determined the whole future life of the turnip-stealer." At once my sympathy was enlisted on behalf of this lad―Harvey Porter―who preferred stealing to starving, but after he had found refuge in the pottery called Brunel's Tower and had become a favourite with the owner my interest in him began sadly to wane. With meticulous care Mr. Phillpotts sets forth his hero's character; no fairer statement of a case was ever made. But granted that a boy of Harvey's upbringing might be puzzled to distinguish clearly between right and wrong, I still wonder whether among his besetting foibles the vice of meanness need have figured so strongly. Specialists in the influences of heredity and environment will revel in a study that is marked by great sincerity, but I have such an affection for Mr. Phillpotts' former work that I cannot offer him a very enthusiastic welcome in his new role of psychologist.

MORE GERMAN LOSSES.

"My brother writers that he's found one of those Uhlans' helmets, and he's sticking to it as a keepsake."

"My! won't the Kaiser be mad!"

"The Guillaume was congratulated by the British Admiralty on its bombardment of Dardanos fort. This vessel demolished powerful batteries, and was struck by two 150 kilometre calibre projectiles."

Dublin Evening Mail.

These 94-mile calibre guns would have been used in the West, no doubt, but that they are somewhat lacking in mobility.