Punch/Volume 148/Issue 3852

CHARIVARIA.

Another snub for the All-Highest. The author of a book bearing the snappy title, What I saw in Berlin and Other European Capitals During War Time," mentions that in Bulgaria he found a man who had not heard of the Kaiser's War.

⁂

Much satisfaction has been caused in Germany by an instance, reported in the London press, of the spread of German culture in England. At one of our Police Courts, last week, a woman was charged with spitting at a police-constable. This method of signifying strong disapproval is, of course, practised by the best people in Germany.

⁂

It is stated that there are now over 150 Germans in Brixton Prison awaiting deportation as undesirables. They cannot, however, be returned to their homes until Peace is declared. Meanwhile, their indignation at the "Stop the War" movement of certain wrong-headed women can well be imagined.

⁂

By the way, we were pleased to see that Madame Juliette Adam, who is seventy-nine years old, wrote a most scathing reply to an invitation to take part in the Women's Peace Conference. It is just the old Adam which these foolish persons leave out of their calculations.

⁂

Anything that will raise a smile in these trying times is to be welcomed, and we desire to acknowledge our indebtedness to Die Welt for the following:—Clad in virtue and in peerless nobility of character, unassailable by insidious enemies either within or without, girded about by the benign influences of Kultur, the German, whether soldier or civilian, pursues his destined way, fearless and serene."

⁂

"SWIFT WORK BY CANADIANS

Hindenburg believed to be in Command."

Daily Mail.

This intimation will, we feel sure, be keenly resented by our gallant Canadian officers.

⁂

A French soldier who, for gallantry in the field, was decorated and kissed by General Joffre, in an account of the proceeding says, "I cannot describe my sensation when I felt the heavy moustache of the General against my cheek." It was only iron discipline, we suspect, which prevented his crying, "Stop your tickling, Joffre!"

⁂

"The English soldier," says Herr Kaltenschnee, of the 6th Westphalians, "notwithstanding that he is possessed of nothing comparable either to the discipline or the military knowledge of the German, has always shown that he is a man, and a brave man to boot." He is also, of course, a safe man "to boot," when you have him maimed and a prisoner.

⁂

The man who described our gallant Tars in the Near East as "The Fruit Salts" went wrong in his anticipation. They didn't land at Enos after all.

⁂

The Daily Express publishes a photograph of a British soldier showing how his hair was parted by a German bullet. The shot, it is thought, must have been fired by a German barber.

⁂

The Weekly Dispatch has published a symposium entitled, "What strikes me most about the War." An officer at the Front says that, if he had been asked to contribute, his answer would have been "Shrapnel."

⁂

Dr. Sven Hedin's book on the War shows that this gentleman was ready to swallow any anti-English yarn that was offered him by the Germans. Possibly it was loyalty to his own calling that made him so peculiarly partial to travellers' tales.

⁂

"In Berlin," says Dr. Hedin, "I was greatly impressed by the worldwide influence of German thought." In Berlin, perhaps; but the centre of things is often a bad place for getting news of the circumference.

⁂

Statistics published by the Tramways Department of the L.C.C. show that there are more fatal accidents on Sundays than on any other day of the week. This looks as if the British Sunday is so dull that people will go to any lengths to get a little excitement.

⁂

"COPPER CONCEALED IN LARD."

Evening News.

One can picture the whole scene. The Force comes down the steps of a prohibited area and enters the kitchen. At that moment the cook hears her mistress's hand on the kitchen door-handle. As quick as lightning she throws her visitor into a tub of lard, where he lies hidden until the danger is past.

⁂

"All the real Quinneys," according to a paragraph in The Evening News, "are writing to Mr. Vachell to ask him how he came to choose their name for his new play at the Haymarket. Incidentally they ask for seats." Mr. Vachell is congratulating himself on not having called the play "Smiths'."

⁂

A seal was seen in the Thames near Richmond Bridge last week, and several gentlemen who, on catching sight of it, took the pledge, were more than annoyed on finding that the apparition had also been seen by teetotalers.

"Oh, that is far too frivolous. Aren't you bringing out any serious toys for the duration of the War?"

We learn from The North Wales Weekly News that the Colwyn Bay May-day Festivities, to take place to-day (Wednesday), will include the "Crowing of the May Queen":—

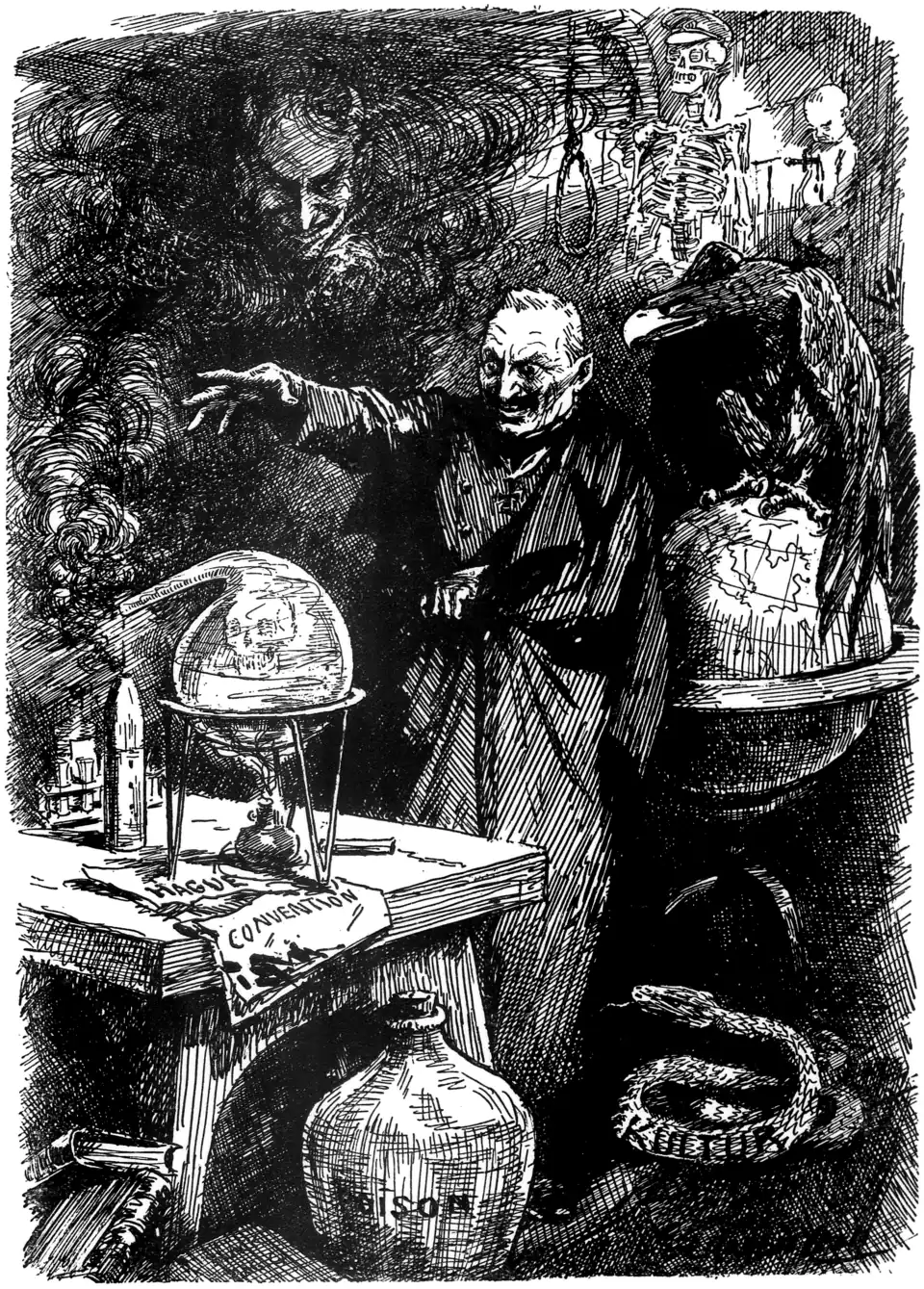

TO CERTAIN GERMAN PROFESSORS OF CHEMICS.

THE GREAT PEACE OF 1920.

By our own Sensation Novelist, temporarily unemployed.

(Author of The Next War; England Attacked; The Empire's Peril, and other like works.)

Chapter I.

Seated here in my study, and looking back upon the tremendous happenings of the past year, I can remember as though it were yesterday the August evening when there burst upon an amazed and wholly unprepared world the news that Peace, so often foretold and as often discredited, had actually been declared by Germany upon England.

What one finds most incredible, in retrospect, was the suddenness of the blow. To a people who had been for years lapped in the fog of war it came like lightning out of a sandstorm, like truth from a Teuton, like anything that is wholly bewildering and unexpected. The newspapers of the day before the great event make strange reading now. All appears to have been going on absolutely as at any time during the past six years. The usual Zeppelins were bombing blackbirds in the suburbs of Sheringham. In The Daily Telegram Dr. Pillon had his habitual article upon "The imminence of Balkan intervention." All, in short, was as long custom had habituated us to it. And then, quite suddenly, the cataclysm.

I have heard since that they had rumours of it in many quarters of London quite early on that afternoon; but the news did not reach us at Woking (where I was then living) before nightfall. Even the late editions contained no more than the intimation of an unusually prolonged sitting of the Cabinet. Smith, my neighbour, who dropped in from number five, Warsaw Villas, for his after-dinner pipe had heard only a vague report of a certain liveliness in Downing Street. So it was actually not till the following morning, when I opened my daily paper, that I knew the truth, saw it staring at me in huge letters right across the chief page—Peace!

Even then, you know, one hardly realized. Not even when Smith himself, purple and incoherent, burst in through the breakfast-room window (which I should perhaps explain was a French one, and open at the moment). "You've heard?" Words failed him. As for me I could only stare, bewildered by something strange and unfamiliar in the appearance of my old friend. Smith indeed had lost no time. Gone was the customary suit of sober khaki that he had worn so long as a private in the Underwriters' Battalion; and instead he now stood revealed in all the panoply of the full dress of the Brookwood Golf Club, scarlet coat, heather mixture stockings, and all.

Smith saw my look, and answered it. "Of course," he cried, "everybody's going. The road to the links is crowded already. It's Peace now, and no mistake!"

Slowly I began to understand.

One remembers that day as a kind of dream. The stupendous change that had come upon everything and everybody! In the train one heard it (for after a moment I had decided that, in spite of Smith, my own place in the hour of crisis was London). Men crowded the carriages, or stood about in groups at the stations, discussing excitedly the one topic. Most of them still wore their every-day khaki, but here and there was one, bolder than the rest, who already displayed, a little awkwardly, some symbol of the New Era—a bowler-hat perhaps, or even an umbrella, held with an air of self-consciousness in hands so long unused to anything more conspicuous than a Lee-Enfield. England, you perceive, was waking gradually.

And the scraps of talk one heard. Almost as unfamiliar some of it as Flemish must once have been. "If you take away State-aid from the Church—" a man would be saying; and another, "The vital question is simply this—can Carson be coerced?" It was really astonishing how quickly they had recovered the trick of it.

I fancy that full and complete comprehension came to me from two sources almost at the same moment. I had bought a score of papers, and torn them eagerly open. Each was more lurid and sensational than the last. Headlines in leaded type swam before my eyes—headlines that I had never looked to read again in this blandly bellicose existence to which I had grown so used. "Where are you going to spend August? "Is sea-bathing deleterious?" "Should children contradict?" and the like. But still I read as in a dream.

Then suddenly I saw two things. First, at the foot of the Haymarket, I observed, making his way through a crowd murmuring with admiration, a knut, a real knut, of the knuttiest age, twenty at most, in absolutely full peace-kit, down to monocle and spats. And almost at the same moment my motor-bus was held up to permit the passage of a column of females carrying banners. What were they? I turned to my neighbour, who, I noticed had grown suddenly pale.

"Suffragettes!" he whispered unsteadily, "walking to Hyde Park for a demonstration! That means Peace with a vengeance!"

It did. At his words the scales fell from my eyes, and I saw the truth of this amazing occurrence. And with that vision came also another thought, one that sent the blood racing to my heart, and froze it there. The girl I loved, the heroine of this work, Clorinda Fitz-Eustace was even now quietly at work as a red-cross nurse in a field hospital. At this very hour perhaps she might be quitting its gentle shade to adventure herself, all unconscious of danger, amid the hazards of Peace. I saw then that it must be mine to warn and save her. But how?

(To be continued.)

[What makes you think that?—Ed.]

THE ELIXIR OF HATE.

Miss Chatsworth Plantagenet (of the Chorus of "The Motor-Bike Girl"). "Isn't this war terrible? D'you know, I can't get any decent grease-paint for love or money!"

THE WATCH DOGS.

XVII.

Dear Charles,—All of us have changed, a little or a lot, under the stress of actual war, but the most dismal case of all is that of our young but highly respected friend, Stevenson. You remember him, of course; simple-minded and kindly-hearted a fellow as you could wish to meet, a lover of small children and dogs, an ardent member of all the Prevention Societies and a peculiarly zealous churchwarden. For some time his cap has been assuming an aggressive, almost vindictive, angle, and his eyebrows grow hourly more ferocious; but so much is forgivable in these days. It is now, however, worse than that. A week ago he informed us, with what I am reluctantly forced to describe as an ugly leer, that he was not accompanying us to the trenches this time, adding that so far from shirking the unpleasant duties of the present he was preparing himself for even more unpleasant purposes in the near future. In short he had secured the office of Master Bombardier of the regiment, and has since devoted all his energies to contriving infernal machines and practising the art of pitching them accurately in tender spots. He is now known amongst us as the Anarchist; is openly accused of all the worst anti-tendencies, and is suspected of having applied to the War Office for special leave to drop the official khaki and assume an independent red in his neckwear. We tell him that his old vocation, Municipal something or other, is gone; but he says that another trade, more sinister and exciting, will be open to him when Peace arrives for the rest of us. His advertisement will read:—"All authority, monarchical, aristocratic or democratic, and all other tiresome restrictions on individual liberty removed with secrecy, ability and despatch. All ceremonies attended and dealt with. Coronations extra." Such a nice quiet fellow he was, too!

It is said that for every man in the trenches there are four outside. But I am told that these others have also their embarrassed moments, and not least the Company Quarter-Master-Sergeants, whose duty it is to keep us armed and equipped, clothed and fed. As modest fellows who dislike being conspicuous, they prefer to work in the dark, and carry up to the trenches our food, drink and fuel at dead of night by means of long-suffering fatigue parties who stumble up from the stores to the trenches as best they can through the mud and shell-holes, hedges, ditches, telephone wires and stray bullets. It is a matter, as I used to write in my legal opinions of long ago, "not wholly free from difficulty," and our industrious "Quarters" prefers, at times, to supervise the loaded procession personally. The other night, what with the rain and wind in addition to the other distractions above indicated, he found it an especially trying operation. Time after time the party broke away into small units, one deviating to the right, another to the left, a third dropping to the rear and a fourth proceeding to a front but, unhappily, the wrong front. With much running hither and thither and much harsh whispering, our Quarters would get them together again and bearing for safety, but the last check of all, occurring when the party were well under fire, was almost, he tells me, fatal. It was in the midst of his searchings on this occasion that he was haunted by the distressed whisper of the one fatigue man he had managed to collect and keep—"Quarters! Quarters!" At such times distress of this sort has to be ignored, but this voice was so persistent as eventually to arrest Quarters' attention. "Quarters!" whispered the voice. "Yes, lad," answered he. "Is that you, Quarters?" continued the voice, changing from the distressed to the chatty. "Yes," said Quarters irritably, since the flare lights were becoming unpleasantly frequent and near, and the identity and whereabouts of the party must soon become apparent to the busy rifles on the German parapet. "Quarters," whispered the voice, with damnable iteration, "I want a new pair of trousers and a cap badge." On my honour, Charles, this is a true bill.

I was present, unofficially, at a discussion yesterday in the trenches, at which four of our less sedate youngsters were debating snipers in general, and, in particular, one of this unpopular class who is suspected of carrying on business in a partly demolished farmhouse on our half-left. They were considering the steps to be taken less to prevent than to punish him. The suggestion of the youngest of the party appeared to me the most subtle; it was obviously reminiscent of his misspent boyhood at home. "I should creep out to the farmhouse door by night," said he, impressively, "and listen for myself to find out if the sniper was inside." "And if he was?" asked the others. "Then," said the incorrigible, speaking slowly and with a due sense of climax, "I should ring the front door bell and run away." Can you conceive anything better calculated to annoy and make justly indignant a wholly preoccupied and slightly nervous sniper?

To show you how richly I deserve the abuse which our regular authorities still continue, even at this juncture, to pour upon my territorial head, let me tell you of my latest and worst iniquity. Last night at 11 P.M. I received a packet of socks, for distribution among my platoon. At 11.15 P.M. I handed the last pair of these to my servant, with a short homily on virtue. At 12 midnight my servant, having given me my last meal of the night, turned in. At 1.30 A.M. I trod in a pool, and at 2 A.M. my chilled feet were carrying me towards my servant's dug-out with felonious intent. Did I not stop at stealing my own servant's socks? No, Charles, I did not. Further and worse, I woke the wretched fellow up to ask him where the devil he'd hidden them. Can you wonder that every time I show my head above the parapet a hundred or so lovers of justice do their best to make an example of me?

Yours, Charles.

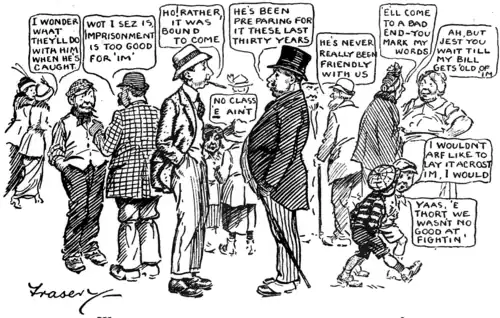

Who can it be that they are discussing?

"SKIRMISHING IN THE DESSERT."

Leicester Daily Mercury.

Presumably this refers to an after dinner raid by the infantry.

"Von Adler, who was tried first, pleaded guilty, and asked if he could afterwards

The president informed him that he could not."—Aberdeen Evening Express.

When we are on the Bench we never allow prisoners to afterwards.

"We cannot hope to satisfy everybody, because it is a problem that has always provoked intense feeling, because everybody has previous convictions."—Pall Mall Gazette (Mr. Lloyd George on the Drink Question).

Not everybody. We ourselves—and there must be others equally stainless—have never been convicted for inebriety.

How they grow young in Russia (Old Style):—

"The eminent composer Scriabin died in Moscow this morning from blood-poisoning at the age of 35... Born on December 29, 1871 (old style), Scriabin went through a musical education..."—The Times.

{{blockquote| "There is at present a splendid opening in the town of Alberton, Prince Edward Island, for a blacksmith, who must be a good shoer, a barber and a teacher of music who can tune pianos and organs."

"Church Life," Toronto.

A chance for our old friend, the Harmonious Blacksmith.

Q. What would become of Thomas Atkins if the commissariat broke down?

A. He would still remain a gentleman—a preux chevalier, sans beurre et sans brioche.

THE PHARISEE AND THE PUBLICAN.

(A Sketch in War-Time.)

ONE day last week a Cheerful Miller met a Despondent Brewer in the street.

"Well, how's business?" asked the Cheerful Miller tactlessly, rubbing his hands.

The Despondent Brewer's reply was clothed in language which seemed to intimate that business prospects were not superlatively good.

"For your own sake, personally, I am grieved to hear it," said the Cheerful Miller. "But of course one cannot overlook certain aspects of your trade that render its decline beneficial to the public at large."

The Despondent Brewer, a blunt, outspoken man, made reply, and made it good and strong. But the cheerfulness of the Cheerful Miller was deep-rooted in prosperity, and was not to he disturbed even by the blasts of the Brewer's despondency.

"Now my trade, happily, is free from any such taint," continued the Cheerful Miller. Pointing to the contents of a baker's shop he said, "Look there; that merchandise never did harm to anyone."

The Despondent Brewer looked, first at the crisp brown loaves, and then at a woman who had entered the shop to buy. The woman carried a baby; two other children were with her, holding on to her torn skirt. The Despondent Brewer saw her place a very large sum of money on the counter and receive in exchange a very small loaf.

Hitherto we have refrained from giving the exact words which the Despondent Brewer uttered to the Cheerful Miller. But we will now tell you exactly what he said.

"Thank God, I'm not a Miller," said the Despondent Brewer.

British Barberism.

"The Lewes Guardians have sanctioned an application by the workhouse barber to take soldiers of the R.F.A., billeted in Lewes, to the workhouse to assist him and to gain experience. It was stated that the officers wished the men to learn some useful trade in addition to military duty. The chairman said he hardly liked the idea of amateurs experimenting on old men's shins, but other members said the barber guaranteed the work being done satisfactorily."—Birmingham Daily Post.

As nothing is said about the opinions of the hairy-legged paupers on the subject, we infer that they are unfit for publication.

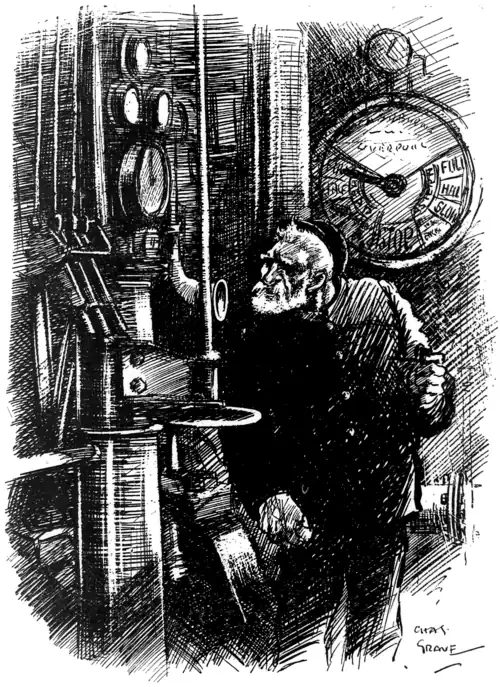

THE TRUE SPIRIT.

Voice of Captain (through tube). "There's a submarine about, Mac. Can you whack her up any more?"

Chief Engineer. "Ay, ah'll get anither twa knots, if I ha'e to burn whusky!"

MY CRIMINAL.

I have seen one at last.

After years of intimacy with the Zoo, during which I have sought in vain for the pickpockets of which so many notices bid us beware, I have had the satisfaction of watching one at work there—as flagrantly as that historic but un-named performer who abstracted a snuffbox from a courtier under the eyes of Charles II., and by his roguish shamelessness made the Merry Monarch an accomplice.

The words "Beware of Pickpockets" had indeed confronted me for so long and in so many places in these otherwise so innocent Gardens that I had come to look upon them as the "Wolf! Wolf" of the fable. Even in the lions' house at feeding time when, tradition has it, the pupils of Fagin are at their very best, I have never detected a practitioner.

But yesterday!

But Yesterday was the first day of blazing sunshine, and having two hours to spare in the afternoon I rushed to Regent's Park, intending to make an exhaustive tour of the whole Zoo. it was so hot and prematurely summery that instead I did a thing I have never done before: I sat on a chair in the path up and down which the elephants slowly parade, bearing loads of excited children and self-conscious adults; and it was there that I found the pickpocket, or, if you like, it was there that he found me. For I was one of his victims.

I had always thought of pickpockets as little chaps capable of slipping away even between men's legs in a crowd; but this fellow was big. I had thought, too, of pickpockets as carrying on their nefarious profession with a certain secrecy and furtiveness; but the Zoo pickpocket, possibly from sheer cynicism, or from sheer advantage of size, making most of the officials look insignificant and weakly, was at few or no pains to cover his depredations. Nor did he, as I supposed was the custom of his kind, devote himself to watches, pocket-books and handkerchiefs, but took whatever he could, and if a bag chanced to have something in it and he could not extract the contents quickly enough he took the bag as well. He was indeed brazen; but scatheless too.

My own loss was trifling—merely a newspaper, which I would have given him had he asked for it. But before I knew anything it was snatched from my hands by this voracious thief. To say that I was astonished would be to state the case with absurd mildness; I was electrified. But when I looked round for the help which any man, and not least a F.Z.S., as I am proud to be able to sign myself, is entitled to expect, judge of my horror when I found that not only all the spectators who had witnessed the outrage, but also the only keeper within sight, were laughing.

Such is the levity which the unwonted sunshine had brought to the Gardens!

And I can swear that the pickpocket was laughing too, for there was an odd light in his wicked little yellow eye as he opened his mouth, lifted his trunk with my poor Evening News firmly held in it, and deposited the paper in that pink cavern his mouth. For my first Zoo pickpocket was the biggest of the elephants, who is both old enough and large enough to know better.

"RECRUITING RESULTS.

Most satisfactory and gratifying.

Insects at the front."

East Anglian Daily Times.

"More for the colours.—This week, three Osbournby lads have enlisted in Kitcheuer's Army, viz., Arthur Bullock, George Bee, and Herbert Bugg."—Grantham Journal.

The Kaiser has threatened to arm every cat and dog in his dominions; but it looks as if our "K." can beat him even at that game.

GETTING A MOVE ON.

We are the Fourth Loamshires. (Dear old Loamshire, my own county—I once passed through it in a train.) Of course there is no such place as Loamshire really, as your little boy would tell you, but I have to disguise the regiment. For why? The answer is "King's Regulations, para. 453, Communications to Press—Penalty, Death or such less punishment as the Court awards." So you will understand that this is purely fictitious—at any rate, until after the war. The name, the events, the documents, the conversations, they are all invented; nothing in the least like this ever happened or ever could happen. My only excuse for writing is that we subalterns have a couple of seconds all to ourselves every morning between the word "Fix" and the word "Bayonets," and that one must do something in one's leisure. "Platoon, at-ten-shun! Fix———" I take my note-book out, and proceed to put down for you this extremely imaginative story...

The rumour started, like all good rumours, in the Sergeants' Mess. "I hear we're going to Blinksea," said the Sergeant-Major, unbending for a moment. "Anywhere out of this blighted place," said the most lately promoted Corporal, just to show his independence. Next day it was all over the battalion.

A fortnight later it was officially announced in Orders. We were going to Blinksea on Monday, and the Blinkshires were coming to our own little watering-spot (Shellbeach) in exchange. They sent one Major and a few men as an advance party to Shellbeach, and we sent two Majors and a few men as an advance party to Blinksea; we were always a little prodigal with our Majors.

As soon as they were satisfied that the advance party had arrived, and that we had all sent our new address home to our wives and mothers, the Authorities postponed the move till Saturday week. We bore it stoically—particularly our Majors. Our Majors immediately wrote that it was hardly worth while coming back such a long way for such a few days; that Blinksea was a delightful spot with a first-class hotel and an excellent golf-course; and that they were longing to get to work again. So they stayed, and on the Wednesday the great pack-up began.

We all had our special jobs. Nobody was safe anywhere. Orderlies popped out from behind every bush and handed you a buff-coloured O.H.M.S. envelope. No, not an invitation to lunch from the King, as one would naturally hope; not likely; just a blunt note from the Adjutant telling you to load Barge No. 3 at Port Edward, or carry Barge No. 3 to Port Edward, or something equally heavy and disagreeable. About a hundred notes went out and not a "please' amongst them. Just a "You are instructed to take the Mess billiard-table down to the Pier. If you require assistance———" and so on. All quite firm.

It was a wonderful time. Even the Captains put their backs into it for once. They looked after the regimental lizard, or watched the Colonel's horse embarking, or told the subalterns to get on with it; no job was too strenuous for them. And by mid-day Friday it was done. Everything had gone—machine guns, horses, stores, ammunition, the safe (I carried this down myself; luckily it wasn't a very hot day), the officers' heavy luggage—it was all on the sea. And by the "officers' heavy luggage" I don't only mean their boots. The Colonel's man, always the first to set an example to the battalion, had left the Colonel with what he stood up in and (in case he got wet through on the Friday afternoon) the cord of his dressing gown; and the hint was taken by us others. I assure you we left ourselves very little to carry with us on the Saturday; the Adjutant himself only had a couple of "Memo." forms.

At two o'clock the Authorities rang up.

"Everything on board?"

"Everything, Sir," replied the Adjutant.

"Quite sure?"

"Everything, Sir, except the cord of the Colonel's dressing-gown and a couple of 'Memo.' forms."

"Well, get those on board, too," said the Authorities sharply.

So they went, too. We were now ready. We had taken an affectionate farewell of Shellbeach. The tradesmen had sent in their bills (and in some cases been paid). The Parson had preached a wonderful valedictory sermon, telling us what fine fellows we all were, wishing us luck in our new surroundings, and asking us not to forget him. At six o'clock on Saturday morning we were to be off.

And then the Authorities rang up again.

"Everything on board now?"

"Everything, Sir. It's nearly at Blinksea by this time."

"Right. Then now you'd better see how quickly you can get it all back again. The move is off."

The Adjutant bore up bravely.

"Is it off altogether," he asked, "or merely postponed again?

"Neither," said the Authorities "It is deferred."

*****

The only excitement left was to see what sort of recovery from an apparently hopeless position the Parson would make next Sunday. On the whole he did well. He preached a lengthy sermon upon the inscrutable decrees of Providence. A. A. M.

THE FIVE STAGES OF TABLE TALK.

New Light on Dr. Johnson.

"She had been married for two years to Mr. Thrale, and Johnson had recently lost his wife when they became acquainted. Dainty, lively, dimpled, with a round youthful face and big, intelligent eyes, they used to see each other continually, and discussed everything on Heaven and earth."—Everyman.

We always suspected that Mr. Percy Fitzgerald was wrong when he sculptured the doctor as a negroid dwarf, but we did not know he was quite so wrong as this.

Vicar's Daughter. "Where did you get those nice khaki mittens, Daisy? Did your mother knit them for you?"

Daisy. "No, Miss. Daddy sent them home from the Front at Christmas."

THE SPECIAL DETECTIVE.

I am a Special Detective. It came about in this way. When the Special Constables were being enrolled I offered my services for duty on Saturday afternoons from 4.30 to 5, so as to allow the regular policeman to go off for afternoon tea. I couldn't volunteer to serve any longer as I had to have a singing lesson at 5.15. However, they refused my offer, and as I still wanted to help I appointed myself an unofficial Special Detective—the only one.

I don't suppose you would ever guess what I was if you saw me in the street, because I always go about disguised when on duty. When I am disguised I can detect things which I should never dream of detecting in propria persona. For instance, were I just wearing my usual clothes and my ordinary face, I should not attempt to interfere with an armed burglar in the execution of what, rightly or wrongly, he conceives to be his duty. I should go home. If the occasion demanded it, I should even go to the length of remaining at home until I had grown a moustache, or a beard, or a whisker or perhaps the complete set, according to the requirements of the character I proposed to assume.

I remember once detecting a desperate villain in the act of emptying a perambulator full of practically new children into the canal at Basingstoke. As I happened at the moment to be disguised in the totally unsuitable garb of a member of the Junior Athenæum Club I refrained from interfering. I contented myself with tapping him on the shoulder (I forget which), explaining my difficulty to him, advising him that I should return in due course and severely arrest him, and finally warning him that anything he might say in the meantime would be taken down, suitably edited, and used in evidence against him.

I then returned to town and commenced at once to grow a luxuriant vegetation of whiskers. You see, it was my intention to disguise myself as an Anabaptist, and then go back to Basingstoke and seize my man, if possible, red-handed; if not, whatever colour his hand happened to be. However, hair-raising is not so easy as it looks, for although I read all the ghost stories I could lay my hand on, and actually spent several hours a day under the forcing-pot in the company of the rhubarb, it was a long time before my whiskers were long enough to infuriate Mr. Frank Richardson.

The consequence was that when I eventually returned to the scene of the crime I found that the villain had completed his thankless task and had in all probability gone home to a guilty meal. The indifference displayed by the criminal classes to their impending fate is proverbial. Yet how this heartless desperado ever summoned up the effrontery to clear off after I had expressly informed him that I was coming back to arrest him passes my comprehension. Anyhow, I examined the surface of the canal thoroughly, but as it was quite smooth, without a hole in it anywhere, it is just possible that I was mistaken, and that the miscreant was only intending to wash his offspring. Or, again, they may not have been children at all, but merely turnips or cauliflowers. Personally, I am often unable to distinguish between a very new child and a turnip. I once mentioned this failing to a friend. He was a family man, and simply said, "Ah, wait till you have a baby of your own," which was a singularly fatuous remark to make, because, as it happens, I have a baby of my own, though only a very small one. What I don't possess is a turnip of my own.

Then, too, there is the important matter of clues. How often one reads in the newspapers that detectives are handicapped for want of clues! From the very outset of my career I determined that I would never be handicapped in this manner, and therefore I have my own set of clues which I always carry about with me. I have got a very good footprint from which I expect great results, a blood-stain, several different kinds of tobacco-ash and a button. Buttons, I have observed, nearly always turn out to be clues, from which I gather that the majority of criminals are bachelors.

The science of deductive reasoning naturally plays an important part in my work and often—just to see the look of amazement on their faces—I amuse myself with a little practical demonstration at the expense of my friends. I well remember how I surprised Uncle Jasper by asking after his cold before he had even mentioned a word about it to me. All he had said was, "Well, by boy, what a log tibe it is sidce I've seed you."

And I have had some exciting experiences. Once I stopped a runaway bathchair at the risk of the occupant's life. I gave myself a medal for that. On another occasion I stopped a cheque just in the nick of time. For this I presented myself with an illuminated address, and only by the exercise of great self-control refrained from awarding myself the freedom of my native town. On yet a third occasion I successfully traced a German spy to his lair. I heard him talking German as he passed me (I was disguised at the time I remember as a Writer to the Signet), and never shall I forget the look of utter despair he gave when I forced him to disclose his real name, which was Gwddylch Apgwchllydd. Next time I bring off a coup—as we call it—I have marked myself down for promotion.

"You'll have to practise a good deal, Sir. There's only two on your target, and one of them is a ricochet, and you seem to have put one on the target of the gentleman on the right, and two on the target of the gentleman on the left."

"Well, you know, I don't call that at all a bad mixed bag for a first attempt."

"A Tennyson letter was sold for £2 15s.; a Thrackerary letter, in which he describes himself as a 'tall, white-haired man in spectacles,' for 9 guineas."

Manchester Guardian.

It's a long, long price for Thrackerary.

"Amsterdam, Monday.

A Zeppelin this morning passed over Schiermonnkoog, proceeding in a wasterday direction."—Cork Evening Echo.

Just to kill time, we suppose.

Mass onslaughts for the recapture of this important position were made by the Germans, but our motor machine guns raked the compact ranks with shrapnel."—Daily News.

The Press Censor has no objection whatever to the publication of this statement so long as he is not held responsible for it.

"It is said that cold water has been thrown on milk records in some neighbourhoods where it is the custom to talk lightly of the thousand gallon cow."—Morning Post.

Dark hints as to this use of "allaying Thames" have been heard more than once.

"If they thought, however, that the spirit of our men had been broken by hiph (sic) explosives they were soon to discover their mistake. Again did our machine-puns do tremendous execution, and the attack was beaten off..."

Devon and Exeter Gazette.

The devastating effect of this form of humour is well-known.

"I see that Willis's Club is shut up, and the news is a little surprising, considering that I was only lunching there the other day."

"Mr. Mayfair," in "The Sunday Pictorial."

The éclat conferred on the club by this visit should have enabled it to keep running for some time longer. Perhaps if he had been dining and not "only lunching" things would have been different.

CANADA!

YPRES: APRIL 22-24, 1915.

Simultaneously with the Private View of the Royal Academy, the Royal Society of tattooists open their Annual Exhibition.

ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

House of Commons, Tuesday, 27th April.—Both Houses engaged in consideration of treatment of British prisoners in Germany. In time past have had sharp differences. To-day united in detestation of barbarities practised upon helpless captives. Idea of retaliation unanimously discarded. As Lord Newton put it, if there is to be competition in brutality there is no doubt that we should be outdistanced. Possible, indeed probable, that one result of the War will be capture of German trade, but, when it comes to brutalities "made in Germany," competition hopeless.

Idea of paying off on bodies of German prisoners in this country the cowardly cruelty dealt out to our gallant officers and men who have fallen into human hands less merciful than Death is unthinkable. Great Britain is not going to soil her hands because Germany has irretrievably fouled hers. Still, something must be done in the way of meting out due punishment to responsible authorities who have encouraged or permitted their subordinates to torture, starve and grossly insult those whom the fortunes of war have left defenceless in their custody.

Kitchener, not given to strong language, put his indictment in a few terse sentences, not based upon rumour but substantiated by unquestioned personal testimony.

"Our prisoners," he said, "have been stripped and maltreated in various ways. In some cases evidence goes to prove that they have been shot in cold blood. Our officers, even when wounded, have been wantonly insulted and frequently struck."

No passion displayed during debate in either House. There is a profundity of human anger too deep for words. But something ominous in the sharp stern cheer which greeted the Premier's emphatic declaration.

"When we come to an end of this war—which please God we may—we shall not forget, and we ought not to forget, this horrible record of calculated cruelty and crime. We shall hold it to be our duty to exact reparation against those who are proved to have been the guilty agents and actors."

Business done.—German brutality to British prisoners taken note of.

Wednesday.—Abroad and at home generally accepted that in Edward Grey British Foreign Office has efficient and trustworthy representative. Nevertheless it is, as the proverb shrewdly says, well to have two strings to your bow. House observed with satisfaction that a second is provided in person of Member for East Denbighshire. Mr. John—that way of putting it suggests allusion in servants' hall to a son of the house—keeps a comprehensive eye on progress of the War. Ahead of most folk, he for the moment concentrates his gaze upon the dawn of peace. To-day invited Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs to say whether, seeing the Government has undertaken that the Overseas Dominions shall be effectively consulted when terms of peace come to be formulated, the fullest facilities will also be accorded to the people of Great Britain and Ireland to make known their views and desires.

Secretary of State, judiciously absent, left that promising lion-cub of the Foreign Office, Neil Primrose, to reply. Answer brief and non-committal.

So far, so good. Our Mr. John next ascended loftier heights. Surveying relations of Austria-Hungary and Russia, propounded detailed terms of separate peace. Provided that Bosnia and Herzegovina are transferred to Servia, Austria undertaking to withdraw personally from association and military co-operation with Germany, Russia making such terms as may be considered advisable with regard to Galicia, Bukowina and Transylvania, would Great Britain and France be prepared to sanction such separate settlement?

Young Primrose shook his head. Couldn't personally assume responsibility of speaking for Allies on such grave matter. Doubtless they would find opportunity of considering the proposal when set forth in Parliamentary Report.

Our Mr. John quite content. Felt that so happy a scheme of settlement needed only to be known to gain acceptance. No desire to push himself forward. But if England and her Allies thought his counsel and assistance of any value they were unreservedly at their disposal.

Lloyd George looked on admiringly. Gallant little Wales, long condemned by obtrusive neighbour to a position of comparative insignificance, coming to the front at last.

Business done.—On Post Office vote Hobhouse gave interesting account of work of his Department. The War has largely increased its labours. Every day trainloads of from eighty to ninety tons of letters and parcels are sent to France. To Egypt and Dardanelles go weekly a quarter of a million letters and five thousand parcels. To the Fleet four and a half million letters and forty-five thousand parcels. "This," Hobhouse modestly remarked, "requires a very efficient organisation."

Thursday.—Ronald M'Neill's most famous parliamentary achievement suggests possibility of exceptional performance as a bomb-thrower in the trenches in Flanders. Stops at home and does almost equally good work in keeping his eye on things generally. Emulous of Our Mr. John's collaboration with the Foreign Office, he brings under notice of still absent Secretary of State particulars that have reached him of a new German device, less barbarous than poisoning the atmosphere with asphyxiating gas as a preliminary to the safe bayoneting of the enemy when found in a state of stupor, but just as carefully thought out.

Export of foodstuffs and other cargoes useful in war permitted to Scandinavian countries on the understanding that their Governments prohibit re-export to Germany. M'Neill has discovered a pretty plan for circumventing this arrangement. Cargoes are consigned in proper form to a neutral Baltic fort. On arrival they are re-consigned to another port in the same or a neighbouring neutral state.

That all in order. But arrangements have been made with the consignee by wily German agents to waylay the ship en voyage, capture it and carry it off. Primrose admits there is something in this romance of the sea. The Swedish Government have issued regulations intended to prevent addition of new chapters. If this proves ineffective things may happen.

Business done.—Chancellor of the Exchequer submitted Resolution affecting sale of alcoholic drinks. Spoke for two hours to House crowded for these times when many gallant members are at the Front. In respect of taxation proposal exceeded conjecture. Duty on spirits to be doubled; on wines quadrupled. Beer tax sensibly increased, even for lighter ales, not in favour with workers on the Clyde and elsewhere, who are turning out munitions of war. Irish Members up in arms against what Tim Healy described as "assassin taxation." William O'Brien breaking long silence declared that effect upon distilling and brewing industries in Cork would be as horrible as if the City were bombarded and sacked by the Germans.

Division challenged, the first since outbreak of war. William O'Brien and his once more Truculent Tim led into Lobby thin party of three. Eighty nine members, including some of the regular Opposition, voted with the Government. Big majority. But there is trouble ahead in the way of carrying's through a drastic scheme.

Schoolmistress. "Well, Freddie, what did you learn yesterday?"

New Boy (after deep thought). "You ought to know—you teached me."

THE GREAT UNHUNG.

The following works though many of their titles are reminiscent of popular pictures, will not be found adorning the walls of Burlington House.

Potsdam: looking East AND West. By W. Hohenzollern.

When did you last see your Father? By General von Kluck. Dedicated by the artist to H.I.H. the Crown Prince.

A Study in Still Life. By the Captain of the Goeben.

Belts. A fancy portrait of Samuel Browne, Esq. By a Subaltern.

Portrait of David Jones, Esq. By Von Tirpiz. An example of this painter's water-colour work. The use of ultra-submarine is particularly noticeable.

Mirage à la Mode. By Enver Bey. (German School.)

The Hay Wane. By a German Remount Officer.

Britannia Ruling the Waves. A North Seascape. By J. Jellicoe. (Sea Chantey Bequest.)

The Non-Fighting "Prince Eitel" Tugged to her last berth. By a U.S.A. Customs Officer.

"A public meeting was held on February 9th at the Popular Town Hall to urge the Government to take over the control of fool supplies."

Times of Ceylon.

Up to the present we have not heard of any steps being taken in this direction; but Parliament is still sitting.

"Revs. Kerr and C. T. Bennett, B.A., will exchange pulpits next Sabbath morning. Evening services will be hell in their respective churches as usual."

Welland Telegraph, Ont.

For choice we should have attended the morning service, in the hope that it might be more like "a little heaven below."

Registrar of Women Workers. "What can I do for you?"

Applicant. "You probably want a forewoman: somebody who is used to giving orders and words of command. I've brought my husband to speak for me."

FOR DARTYMOOR.

A Patriotic Criminal.

From a list of recruits in a Welsh parish magazine:—

"George ———, Burglar, 'Pals' Regt."

More German Piracy.

"Para el Domingo en la tarde se anuncia la festiva comedia alemana 'Charley S'Tuntt' (sic)."—El Diario Ilustrado (Chile).

We are accustomed to the Germans claiming Shakspeare's plays as part of their national drama,but when they try to annex the late Mr. Brandon Thomas's masterpiece it is time to register a protest.

A RIGHTEOUS PROTEST.

The Imperial Person beckoned to the General to approach.

"Have you blown up the Cathedral?"

"Yes, Sire."

"And bayoneted the wounded?"

"Yes, Sire."

"And shot all the women and old men and children?"

"Yes, Sire."

"And made arrangements for tomorrow for the white flag ambush?"

"Yes, Sire."

"And for the issue of dum-dum bullets?"

"Yes, Sire."

"And of asphyxiating gases?"

"Yes, Sire."

"Then you had better get on with the report to the Neutral Powers protesting against breaches of the Hague Convention by the Enemy.”

A Mare's Nest?

"Births.

Clark.—On April 19th, at Little Gaddesdon Rectory, Berkhamsted, the wife of the Rev. Edward's Horse, aged 23."—Herts Advertiser.

COMMITTEES.

"This world," sighed Francesca, "might be a happy place if it were not for its committees."

"That," I said, "has all the appearance of an apophthegm. Francesca, do you know what an apophthegm is?"

"Of course I do," said Francesca. "What I said was an apophthegm. I didn't know it when I said it, but I know it now, for one who is wise above ordinary mortals has told me so. I can do lots more at the same price and all equally good. 'God helps them that help themselves.' 'Virtue is its own reward.' 'Misfortunes never come singly.' 'Still waters run deep.' I could go on for ever."

"Yes," I said, "I'm sure you could, but they're not all apophthegms. Some of them are proverbs, and ———"

"Surely at this time of day you're not going to tell me what a proverb is. It's the wisdom of many and the wit of one—there, I got it out first."

"I was not," I said, "competing with you; but I insist on telling you that an apophthegm is a pithy saying and you don't know how to spell it."

"P-i-t-h-y," said Francesca. "Next, please."

"I did not refer to the paltry word 'pithy.' I referred———"

"Well, anyhow, I warn you that I once got a prize for spelling at school. It was called a literary outfit—a penholder, two gilt nibs, two lead pencils and an ink-eraser, all in a pretty cardboard case with a picture of St. Michael's Mount on the lid. Cost, probably, sixpence, but I never inquired, because you mustn't look a gift box in the price, must you? There's another apo-what-you-may-call-it. I'm simply pouring them out to-day. Oh, yes, I know that 'embarrass' has got two r's, and 'harass,' poor thing, has got only one, and I know any amount of other perfectly wonderful tricks. I'll outspell you any day of the week, and you can have the children to help you."

"Francesca," I said, "your breathless, babble shall not avail you. I've got you, and I mean to pin you down. How do you———"

"Stop stop!" she cried. "You can't mean that you're going—no, a man can't be as wicked as that."

"Wicked or not," I said, "I'm going to ask you to spell apophthegm."

"Yes, but don't actually do it. Keep on going to do it as much as you like. Let it be always in the future and never in the present."

"Francesca," I said, "how do you spell apophthegm?"

"I never do," she said; "I should scorn the action."

"Don't niggle," I said. "How does one spell the word?"

"One doesn't," she said. "It takes six people at least to do it; but I'll ring for the maids, if you like, and call the children in, and then we'll all have a go at it together."

"Thank you, I can do it alone." Thereupon I did it.

"Yes," she said, "that's it. You can go up one. It's a funny word, isn't it? There's a sort of Cholmondeley-Marjoribanks feeling about it. And to think that I should be able to make a thing like that without any conscious effort. It's really rather clever of me. You can spell it, but I can spell it and make it too. Good old apoffthegum."

"And now," I said, "you can tell me about these committees that are depressing you so much."

"Oh, but I'm not depressed now. I'm quite gay and light-hearted since I found how beautifully you could spell———"

"We will not mention that word again, please."

All right, we won't; but remember, I didn't begin it. You tried to crush me with it, you know, and I wasn't taking any crushing, was I?"

"Francesca," I said, "your language is deteriorating."

"How well you pronounce," she said. call that deteriating."

"Most people Never mind what they call it. Tell me about your committees."

"It's only that there are such a frightful lot. There were plenty before, and the war has brought hundreds more into existence."

"Well, what of that? The men who are too old or too infirm to go to the front must do something to help, and———"

"There you go again," said Francesca scornfully. "Men! Men belong to these War Committees. Their names are on the lists, but it's the women who do all the work."

"And get all the praise," I said enthusiastically. "There's scarcely a Committee Meeting at which votes of thanks to the Ladies' Sub-Committees aren't passed. Still, there are a lot of Committees. They do seem to grow on you, don't they?"

"Yes," she said. "It's like keeping dogs. You begin with a small Committee, a sort of Pekinese, and you get a reputation for heing fond of Committees, and in a few months you find you've got a Committee on every sofa and armchair in the house—St. Bernards, retrievers, spaniels, and all sending out notices and requiring you to attend."

"Your metaphor," I said, "is getting a little out of hand, but I know what you mean."

"Thank you, oh, thank you. And then there's old Mrs. Wilson who has eight children and a husband who ought to have followed the King's example, only ten times more so, and hasn't done anything of the sort. She requires about a whole Committee all to herself, and she isn't the only one."

"The fact is," I said, "that if Committees didn't exist you'd have to invent them."

"But they do exist," she said, "and we keep on inventing them. We're going to invent a new one to-night—the chocolate and tobacco Committee for the county regiment. We have to co-ordinate things."

"All Committees have to do that," I said. "Co-ordination is the badge of all their tribe."

"Is that an apophthegm?" she said.

"No," I said, "it's almost a quotation."

R.C.L.

THE WISE THRUSH.

HOW TO MAKE GOLF POSSIBLE IN WAR-TIME.

A FEW SUGGESTIONS FOR EASING THE PLAYER'S CONSCIENCE.

AT THE PLAY.

"Betty."

The story of Cinderella being the best story in the world, and each new Cinderella giving it freshness, any play based upon it is fairly certain of success. So Betty, by Miss Gladys Unger, and Mr. Frederick Lonsdale, should be in for a long run at Daly's, for not only is the Cinderella theme deftly handled, but in Miss Winifred Barnes a very sympathetic actress has been found for what is probably the most sympathetic part that the wit of storyteller or dramatist will ever devise.

Two surprises are in store for the habitué of this comfortable theatre: one agreeable and the other disappointing. The agreeable surprise is that for the first time a musical comedy has some real acting in it, as distinguished from the facile singing and dancing and talking of the pleasant ladies and gentlemen upon whose shoulders the slender burden of dramatic verisimilitude in such pieces usually rests; and the other surprise is that, for once, Daly's has little but thin and very ordinary music. The acting is contributed principally by Mr. Donald Calthrop and Mr. C. M. Lowne, both new-comers to musical comedy. Their gifts are welcome because the Audience has to be persuaded of the reality of the young scapegrace peer and his father the duke's indignant aristocratic tyranny. Without this reality we should not be sufficiently touched by the position of Betty, the kitchen-maid so capriciously selected by the young lord as his wife; and to be touched by her is of the essence of the play. Miss Winifred Barnes herself sees to that too, although it is Mr. Calthrop on whom the chief responsibility lies, and he succeeds admirably; but Miss Barnes is charming in her simple sincerity, and her singing completes her conquest.

The humorous honours go to Mr. G. P. Huntley, who has never been funnier or kindlier. Nor has he ever been more idiosyncratic. I came away with the feeling that he ought permanently to adopt this role of the short-sighted, warm-hearted, affable, idiotic yet fitfully shrewd Lord Playne; that some arrangement should be come to by which in this character he should be made free of the stage of all other theatres, to wander irresponsibly through whatever other plays most needed him. I would not even confine him to one theatre; he should do two or even three houses a night, if necessary. Every play thus adorned, I care not by whom written, would be the better for it. And yet, in Betty, Lord Playne has a real place; he is important if not necessary to the story, whereas poor Mr. W. H. Berry, who has so often destroyed my gravity at this house, is not. The trouble about Mr. Berry's part is that it is obviously an afterthought, added as an embarrassment of riches. Neither he nor his sprightly feminine foil, Miss Beatrice Sealby, is in the picture, nor has Mr. Berry, who is one of the best of our comedians, anything yet to do that is worthy of his gifts. Time, however, is always on the side of such performers; more jokes will be dropped in and funnier songs substituted. I feel perfectly confident that in a month's time Mr. Berry's part will be adequate once more.

The last scene, of which (no doubt to the intense astonishment of the audience) a staircase is a prominent feature, is gay and distinguished beyond anything now on the stage; and I congratulate Mr. Royce on his triumph. But I retain as the most charming pictorial moment of the evening Betty's appearance in her going-away dress in Act II. That dress is the prettiest thing in London. V.

At the Palace Theatre, on Tuesday next, May 11th, at 2.30, Messrs. Vedrenne and Eadie are to give a matinée of the popular play, The Man who stayed at Home. The performance is in aid of The Officers' Family Fund, of which the Queen is Patroness and Lady Lansdowne President. The King and Queen have graciously promised to attend.

"Kearney—April 24, 1915, at 8 Grantham Street and 59 Upper Stephen Street, Dublin, the wife of J. C. Kearney, of a daughter (both doing well)."—Dublin Evening Mail.

Miss Kearney appears to have solved the problem which puzzled her fellow-countryman, Sir Boyle Roche.

"Mr. Fred T. Jane's lecture in the Free Trade Hall last night was in reality a discursive but very interesting talk about the navy lasting for two hours.—Manchester Guardian.

From a perusal of Mr. Jane's remarks we are relieved to learn that in his opinion the Navy will last considerably longer than this.

Looking for Trouble.

"Theft of Cash and Bank Notes

Liability to Third Parties

Damage to contents by Bursting of Pipes is surely worth having when obtainable

at ABOUT THE USUAL COST.May wo arrange one for you?"

Advt. in "The Friend."

There may be a demand for these misfortunes, but personally we have no use For them.

THE INSULT.

"It's my belief you don't know nothing about anything," declared the public-house orator, exasperated to an unusual degree by the continued silence of the big, stolid-looking man sitting opposite him.

The silent man raised his eyebrows and waved his pipe in the air, to intimate that he took no interest whatever in the orator's beliefs or disbeliefs.

"Garn, you don't know there's a War on," said the argumentative one, tauntingly. "Leastways, you don't know which side the Rooshians is on." This thrust also failing in its purpose, the speaker was emboldened to proceed.

"It's my belief you don't care who wins the War, so long as you ain't hurt." The man remained unmoved.

"You're a pro-German, that's what you are, and I always had my suspicions."

The silent man stared up at the ceiling and slowly put his hands in his pockets.

"You agree with them blokes what says we ought not to hurt Germany more than we can help."

The listener beat a tattoo on the floor with his heels and thrust his hands yet deeper into his pockets.

The argumentative man was nearly at the end of his tether. "Nothing can't move you," he said angrily.

"You can't," declared the other without removing his pipe from his mouth. "It ain't worth my while to argufy with you. Waste o' breath."

"Oh, waste of breath, is it? You're a Hun, that's what you are, and your missus is a Frow, and your kids is little Willies."

The silent man appeared to be faintly amused. "Go on, Roosyvelt," he said.

"I've finished," answered the orator, rising to go. "It ain't no use talking to an Independent Labourer."

"A what?" said the big man, uncrossing his legs and taking his hands out of his pockets.

"An Independent Labourer," was the triumphant answer. "That's what you are. One of Keir ..." The sentence remained unfinished. The silent man's fist shot out, and the orator found himself on the floor staring at an angry face bending over him.

"Say that again," challenged the big man.

"No," replied the fallen hero. "I'll shake hands instead." He rose cautiously, rubbing his head. Then smiled ruefully and said, "Anyway, I did wake you up in the end."

Pal (from within shouting distance of German trenches). "How many of ye's there?"

Voice from German trenches. "Tousands!"

Pat (discharging jampot bomb). "Well, divide that amongst ye!"

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

The industry of Mr. G. B. Burgin seems only equalled by the fertility of his invention. This reflection was evoked by my discovery, opposite the title-page of The Herb of Healing (Hutchinson), of a list of forty-eight other books by the same author. It makes me blink. Of course, when any human writer has so many pages to cover he must of necessity spread his plots a little sparingly. The plot of Herb of Healing, for example, is rather thin stuff, the quest of a lover called Old Man (he was but twenty-four really, so the name is misleading) for an Indian herb which should restore the consumptive schoolmistress whom he loved. You guess that Mr. Burgin is here back again in the Ottawa setting, where you have perhaps enjoyed meeting him before. There are other interests, notably Miss Wilks. In many ways indeed Miss Wilks deserves to be called the chief personage of the story. She was a mule, wall-eyed, and of such super-asinine sagacity that I began at last to find her some tax on my credulity. Not once but many times does she rescue the good personages, with heels and teeth, from the attacks of the evil-minded. Dialogue is freely ascribed to her. At one time she goes of her own accord to be re-shod in preparation for the journey of her master. Hereabouts I began to be haunted by a memory of similar quadrupeds that I had seen on the pantomime stage. Eventually of course the herb is found, the schoolmistress restored to health and the lovers united. My only surprise in all this was that the mule did not join their hands. A pleasant, ingenuous story, which will bring much content to the admirers of Mr. Burgin and the lovers of tall animal tales.

The Prussian has not exactly the knack of making himself devotedly loved even in peace time. Going for him in When Blood is their Argument (Hodder and Stoughton), Mr. Ford Madox Hueffer frankly adopts the bald-headed method. The South German blood in him and the remembered tradition of an older, simpler, well-beloved Germany add a bitterness which no mere outsider critic can command. You might sum it up as the quarrel of the Artist with the Professor (German: New Style), with all his nationalised, organised Kunst and Kultur, his killing of the spirit with the (dictated) letter. He thinks it is the German Professor who has scotched for ever the leisurely scholarship which expanded over the port wine, and has replaced it by a formidable and loathly apparatus of meticulously futile cramming labelled Philologie. He airs the interesting thesis that Goethe as the literary Superman was deliberately manufactured, in first instance, by Falk, the evil genius behind the Kulturkampf which led Bismarck to his Canossa; that the incomparably greater but intractably liberal Heine was relatively and as deliberately diminished. As to Bismarck himself, he was "a very great, very human and quite amiable figure." That actor-manager autocrat, Wilhelm II., is the real villain of the piece, and the Professors, threatened and controlled to an inconceivable degree by a tyrannous bureaucratic direction, mere dishonest mouthpieces of official doctrine. Mr. Hueffer has written an intriguing, inaccurate and incoherent book, but he creates his impression. He has "cast his stone at the rat of Prussianism," as he set out to do. And he can be very annoying, as when he opens his epilogue with a spasm of elegiacs and "I was lying in bed one morning in September, 1914, reflecting on the death of Tibullus." I felt that the superior person, restless during the earlier chapters, had at last broken out, and being a "general reader," and as such frequently put in my place throughout the book, I was annoyed. Besides, what is to become of Mr. George Moore's monopoly of this sort of thing?

From childhood Michael Repton felt the call of the forest. He dreamed strange dreams—or dreamed often the same strange dream—of trees and still water. Elstree and Winchester wrought a temporary cure, but, as he drew to manhood, the woods became more and more of a necessity to him, till finally he obeyed the call. That is the main theme of Behind the Thicket (Max Goschen), the first novel of Mr. W. E. B. Henderson. It is a curious, arresting book, loosely constructed yet never lacking grip, an odd blend of realism and mysticism, of fantastic imagery and careful delineation of ordinary middleclass life. If Mr. Arnold Bennett were to collaborate in a novel with Mr. Arthur Machen, each to have a free hand, they would produce something very like it. This is not to say that Mr. Henderson falls short in originality, for that is the last charge that could be brought against him. It would be easy to be flippant about Behind the Thicket, and still easier to be over-enthusiastic. I am saved from the former blunder by the genuine fascination of the tale; from the latter by an intermittent facetiousness (quite out of place in a novel of this kind), which finds expression in such sentences as "the moral peculiarities of ladies odolized—tut! idolized—by a grateful nation," and "he would not fetch and carry, though she looked fetching and carried on." I cannot better convey my admiration for the book as a whole than by saying that these and similar horrors jarred me like blows. But it would be uncanny if a first novel were to be flawless, and Mr. Henderson's mistakes are few and easily corrected. Behind the Thicket is not great work, but it has so much promise in it of better things that one feels justified in looking forward to the time when its author will produce something to evoke what Mr. W. B. Maxwell has called "the emotions experienced on widely differing occasions by stout Cortez and slender Keats."

A sad interest attaches itself to a passage in the Preface which the late Mr. Frank T. Bullen wrote for his Recollections (Seeley, Service) where he states of the book, "I really believe it may be my last." He died while the volume was being published. No doubt, therefore, this collection of his random memories—"the reminiscences of the busy life of one who has played the varied parts of sailor, author and lecturer," and from whose written and spoken words so many have drawn a sincere pleasure—will command many friends. To be honest, the chronicles themselves, though they contain many diverting sketches of experiences in a lecturer's life, with chairmen, hosts, lanternists and the like, are for the most part rather small beer. Missed trains and railway waiting-rooms may seem to play a disproportionate part herein, to those especially who do not share Mr. Bullen's sense of the minor discomforts of life. The fact is that the real attraction of the book has lain (for me at least) in its revelation of a singularly simple and unaffected personality. Things that many of us are apt to take for granted appear to have preserved an unusual freshness for the author of The Cruise of the Cachalot. I like him, for a random example, upon the hospitality of Fettes, which "went far to convince me that the lecturer's life was a charming one, the people were all so pleasant, so eager to make one happy and comfortable. Moreover, it was a delight to address the lads. Of course it was impossible to tell how they would have received the lecture had they been perfectly free agents, but that is one of those things about which it is well never to show too much curiosity." A remark in its mingled shrewdness and amiability very typical of the man.

Those who like to retain some visible souvenir of their charitable actions should send to Mr. Anthony R. Barker (491, Oxford Street, W.), for The First Belgian Portfolio, containing six sketches of peaceful scenes over which the fury of War has lately passed. The entire proceeds of the sale of these drawings are to be given to the Belgian Relief Fund. The contrast of light and shade in his studies of Dinant and Namur may be a little fierce and his treatment of the romantic Château de Valzin, in the Ardennes, not quite perfect in construction; but his sketches of a wharf-scene at Antwerp and a winding poplar avenue in Flanders are touched with a very pleasant imagination.

"They tell me there's not much to be seen when they sink one of them submarines—just a few bubbles and spots of oil on the surface!"

The Censor Napping.

"The E 15 belongs to a class of sixteen submarines. Built in 1911, she steamed (sic) ten knots below the surface, and sixteen above."

The Irish Times.

What was the use of our gallant sailors facing fearful odds to prevent the secret of the E 15 falling into the enemy's hands if it was to be given away like this?

"Young Lady, R.C., dark, musical, moderate means, desires meet educated Gentleman, same faith, comfortable income, sot over 40; view matrimony."—Liverpool Echo.

The young lady will find it difficult to gratify her peculiar taste in husbands. The article required happily grows scarcer every day.