Stokes on Memory/Mnemonical Clues

There is a great difference between "the thread of a story" and a "chain of ideas;" sometimes there ap-

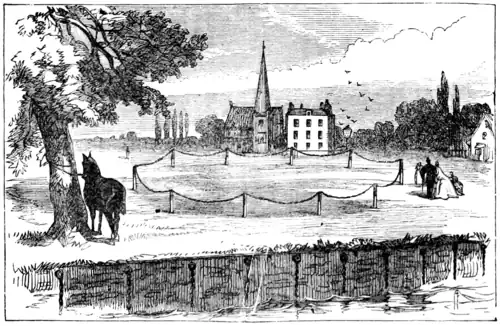

pears to be neither in that which we wish to retain, in which case it may be desirable to make one. The characteristics of the things to be remembered must determine when we shall run a thread, or form a chain. Both plans are Mnemonical, and the associations of which the thread or chain is composed, may be throughout Artificial, but, if properly carried out, either method may be of equal service, according as occasion may require. The anti-Mnemonists argue that the thread may be broken, or that the chain may be snapped, and that then neither would be of use; but if they are well made, there need be no fear of such an occurrence in some instances, and in others the Mnemonist will know in an instant which method to use, and how to use it effectually, as illustrated in the engraving.

RECAPITULATION.

Symbolised mnemonics.

Those who object to take great pains with Mnemonics, may take small panes of glass in a dwelling-house window, and may thus get their mind in the right frame to understand local arrangement; or, if they prefer employing another principle, they may use the various objects in the house with success.

For instance, a stove, with its appurtenances, would be a great (grate) assistance. With such simple means, an intellectual blaze may be produced with a spark of Mnemonical intelligence. The ancients, we are informed, worked mainly thus with houses, associating ideas for their Mnemonical improvement in each room; but it has been found that in this there was room for improvement, for some such objects shun, or have, to their use, a strong objection.

STOKES'S MNEMONICAL TIME ECONOMIZER.

Time, to a man is more than cash,

So waste it not by talking trash;

In few words say all you require,

And then without delay, retire.

To aid you, as you watch his face,

A watch-face there in fancy place;

Or clock-face (think you face a clock),

Which curious plan will no doubt oc-

casion you, without much trouble

His and your own spare time to double!

This gentle hint rarely fails to suggest even to the most inveterate gossippers, loiterers, intruders, and time infringers generally, the desirability of beating a retreat as speedily as possible, and is declared by many business men to be one of the most valuable things ever placed in an Office.

May be had on card of all booksellers, price 2d, or by post 3d.

MNEMONICS APPLIED TO UMBRELLAS.

That many people have an unfortunate habit of forgetting, and consequently of losing, their umbrellas, is a fact of which just one or two of my readers may possibly be already aware. An umbrella worn out in the use of its original purchaser would be considered by some I know, to be a curiosity of almost sufficient interest to be worthy of a glass case, and a place in the British Museum. "Will Mnemonics apply to umbrellas?" is a question which has often been put to me with such serio-comic anxiety, that, for the public good, I feel compelled to answer "Yes;" and to show its application, regardless of the possible unphilosophical unpopularity I may thereby incur from certain members of the Sangsterian fraternity, I can give you a choice of two distinct methods,—you can either have a lingual or a visual reminder. Acquire the habit of saying, "No, thank you, umbrella!" "No, thank you," you must utter aloud, but the word "umbrella" you must say mentally. The result will be that, some day, when you are making a purchase in a shop, in reply to the inquiry, "Anything more, please?" you will say, "No, thank you" (umbrella!!!) and will add to yourself, "Well, if it had not been for Mr. Stokes, I should have left my umbrella behind, for a certainty." But it sometimes happens that umbrellas are lost under other circumstances. There may be nobody near to awaken the suggestion, in which case you can insure remembrance by using a visual reminder. Accustom yourself to see, in imagination, your umbrella opened, and obstructively lying in the doorway, as indicated in the engraving, inviting you not to forsake a friend when the sun shines on you, that you would assuredly seek on a rainy day.

You will not find it difficult to adapt these suggestions to your own special requirements. Sticks, gloves, and overcoats may be thus preserved. A stick in the passage as a leaping bar, your gloves on your friend who is "shaking hands," and your overcoat on the arm of the cabman you are paying, are Little Mnemonical imaginings which will commend themselves, not for their poetic, but for their practical character.

SYMBOLIZATION.

Mnemonical Representation of St. Paul's Cathedral, and the name of its Architect—Wren.

Symbolization is a branch of the Mnemonical Art, and though its application may seem formidable, or often impracticable, to those who are not acquainted with it, it is far too valuable to be passed by here without further notice. Many people seem singularly devoid of symbolizing power, yet their uncouth or imperfect mental representations may be comprehended by themselves, and may be useful to themselves, although not communicable to others.

Experience will soon show that it is often easier to think of a part instead of a whole, and to think of the concrete instead of the abstract; thus, if St. Paul's Cathedral were mentioned, it would be easier to think simply of the upper part of it, as a symbol, than to try to bring to mind its whole exterior and interior, and the upper part alone would suggest St. Paul's quite as well as the thought of the entire building; and suppose we wanted to teach a child that the name of the architect of St. Paul's was Wren, the symbol of the name, a wren, would be more easily remembered than the mere utterance of the name. The straw in the wren's beak, the symbol of its being in the act of building, would be more easily remembered by the child than the word architect, yet would be in effect the same. Test this, if you doubt its power. Tell a number of small children the simple fact that St. Paul's Cathedral was erected by the architect, Wren, and the majority of them probably will soon forget that which you have said.

Then convey the fact symbolically, as given, and if the symbol is not more powerful than the ordinary verbal statement, it will be strange.

Now should this picture seem to make

Associations slender,

Just use the last word of this rhyme,

Which strong the link may (w) render!

Impressions made thus to minds that are awake to this mode of action, are very quick and enduring. Availing myself of the knowledge of this fact, I am certain that thousands who read this book, "Stokes, on memory," will, through this illustration, have my name inseparably connected with the objects used. Thus, while apparently I have been merely illustrating the application of a principle in fixing a fact, I have simultaneously, to thousands of minds, rendered St. Paul's Cathedral—that fane of Fame, to be associated with which so many celebrities have aspired in vain—a stupendous monument to the Stokes, of Memory, and, in time to come, to the Memory of Stokes!

On the principle of involuntary suggestion, you will be surprised to find how frequently you will think of "Stokes, on Memory," in future, owing to the sight of some object to which I have alluded; or to the observation of some fact to which I have referred.

I have intentionally associated myself with many things, in order to produce this result; for it is most desirable for the furtherance of Mnemonics that my name should be a "household word." With many of my pupils, and with those who have a practical knowledge of my System through my public lectures and from my works, my name is habitually used; and if they wish to remember anything, they say, "I must Stokes that," which often occasions inquiry in those who would otherwise know nothing of the matter. Everybody may thus aid me by mentioning my name, by recommending the purchase of my works, and by suggesting the adoption of my System. I urgently solicit this favour of all those who have benefited by my labours, and who approve of my plan.

Let each of my pupils and appreciative readers regard himself as a kind of intellectual missionary, and endeavour to aid me in disseminating principles which are assuredly destined to triumph, sooner or later, and which, in triumphing, will bless mankind.

When there exists a great evil which we would annihilate; wien vast obstacles stand in the path of progress; when difficulties are numerous, formidable, and diversified in their characteristics; when we find we are opposed, or if not absolutely opposed, when we find we are disregarded,—it is questionable policy to adopt the untruthful device of endeavouring to make it appear that everything is just as we would have it. It is true that Mnemonics is a Science of origin Divine; that its principles pervade all minds; that from the creation until now, their operation has been unceasing; that records of the achievements of the Mnemonic Art have been handed down to us almost from time immemorial; that many of the mightiest men of learning and genius have been its humblest disciples, its most grateful friends, and its most zealous advocates. All this we know. Yes; it is true that genius has worshipped at its shrine, and learning most profound has done it honour,—yet it is True, most lamentably true, that, notwithstanding the records of the past and the achievements, triumphs, and trophies of the present, the "educated," the intelligent masses—the world—know not, and seem not much to care to know its wondrous worth. The adoption of the Science by a few paltry thousands cannot be regarded as anything, when we consider the countless myriads peopling the earth—when we realize the fact that Mnemonical thinking is as essential to the proper exercise and full development of

our intellectual existence, as proper breathing is to our physical being; in spite of all that has been said and done, we may say comparatively—almost absolutely—that the Science of Mnemonics is a thing unknown! Where it is known it is too often known only to be ridiculed, despised, maligned, and rejected. Why should we try to hide these facts? Facts they are; then let us acknowledge them, face them, combat them, and, if possible, let us overcome them! Let us hope that the day will come when it shall be considered as great a disgrace not to practice Mnemonics, as it is at present not to read! What must we do to hasten this? Success or failure depends entirely upon those who are now the avowed friends of Mnemonical Science! No movement can thrive, or even exist long in a state of vitality, without organization—without a head—without intelligent co-operation. The merits and claims of the Science of Mnemonics have been explained and demonstrated with sufficient clearness; it remains now only to make them more extensively known, in order that they may be adopted. We may learn a valuable lesson from unfortunate experience. But little good has ever arisen from the contentious discordant bellowings of the egotistical and antagonistic herd of "wonderful discoverers," "great inventors," "remarkable improvers," and "only able teachers." Mnemonics is in its present degraded condition, not because it has had no advocates, but because it has had too many—because it has had many friends, all enemies—because there have been many Systems, but no System! There are two distinct species of Mnemonical ability—the creative, and the appreciative. The former of any worth, for the purposes of dissemination, is comparatively rare. Let those of creative talent unite and work harmoniously for the general good; and let the appreciative, as with one mind and with one voice, experience and assert the value of one plan, or of one many-plan-formed Science. The necessity and great advantage of organization and united effort must be apparent to all who are tolerably clear-sighted. Although much that has been written against Mnemonics as a Science, is fallacious and unjust, yet it is certain that it is in many cases right as regards the particular "Mnemonics" upon which the assaults are made. Much positive harm has often been done to the Science by those who have been actuated with the very best motives; attempts have been made by really clever Mnemonists to convey to the world, in print, that which they themselves understood as well as their alphabet, but which, to the general public, was almost "like Greek," and which could only be communicated properly, to many minds, by the most careful verbal explanations.

These published "explanations," or rather "mystifications," which, if comprehended as intended by their writers, would have been most valuable, have invariably been misunderstood by a great many who have studied them; and these non-comprehending readers have produced a multiplicity of so-called "improved" systems, in which they enumerate an immense number of "defects" and "objections" regarding the plans from which they have derived their Mnemonical "knowledge," and then proceed to make a variety of alterations, which, instead of being "improvements," are positive deteriorations, merely originating in their own want of perception. When systems have gained a certain amount of popularity, the desire to "make a name" has undoubtedly actuated many to endeavour to "improve" upon them, or, at all events, to try to get the credit of improving upon them. But a far more frequent cause of the production of "New and Improved" Systems, has been dishonesty on the part of their producers. Many who have taught Mnemonics havo had the meanness and ingratitude to speak against those who instructed them, and have untruthfully professed to have made various "discoveries" and "improvements," simply in the hope of obtaining pecuniary advantage—in fact, with the endeavour of robbing their instructors of both credit and cash. The history of Mnemonics affords records of such unprincipled behaviour having taken place hundreds of years ago, and it has been more than once attempted in reference to myself. At the urgent request of several ladies and gentlemen, who have been made the subjects of attempted, and in some cases, of actual, imposition, in order to put the public on their guard, I am induced to make known a few facts which, from their very unpleasant character, I should have preferred, if possible, withholding. Owing to my great success, I have been compelled, for several years, to have "Assistants." One of my nominal "Assistants" I deputed to represent me in public, and he had the cool impudence to mount my platform, repeat one of my lectures, illustrate with my pupils, and to call them his, putting forward his name to the entire exclusion of my own. I was, of course, compelled to dismiss him. As he has since been endeavouring to obtain pupils by designating himself "late of the Royal Colosseum," where this took place, and as he was the only person who ever conducted my illustrations there, besides myself, the publication of this fact may, perhaps, sometimes serve him as a "letter of introduction."

On another occasion, I sent a "representative" into a large town, and, after a few weeks' absence, he wrote to me to say, that to prevent any mistake in the delivery of his letters, in future I must address him as "Mr. Stokes"—the people generally had taken him to be "Mr. Stokes," and he had not taken the trouble to undeceive them. At the same time he desired me to send him £10 at once, as he had been living beyond his income, and if I did not comply with his request, if ever I went into that locality, I should find my name in "very bad odour." This was a man of classical education, and he was, till then, of supposed respectability. I immediately had my portrait engraved on steel, for my little book, and the London Stereoscopic Company have since published my "Carte," which is rather unfortunate for those who wish to personate me. Several other unprincipled people have attempted somewhat similar deceptions and frauds, but have generally been frustrated, as, where my name is mentioned, those to whom application is made, are usually sufficiently keen to write to me to ascertain if the statements made are reliable; and when a self-styled "improver" presents himself, he is at once regarded with suspicion, as I only impart my system to those who agree not to teach Mnemonics except with my sanction, and in conjunction with me. The desirability of enforcing this restriction becomes daily more apparent, as some of my pupils have, for their own personal benefit "improved" my system to such an extent that, until they again employed it in its original condition, it was useless.

"NEW AND NATURAL” SYSTEMS OF MEMORY.

While speaking of the difficulties against which Mnemonics has had to contend, there is one phase of the matter which requires especial notice. Many knowing "Mnemonics," or "Artificial Memory," to be unpopular, have joined in the cry raised against it, but have, in reality, taught it under another name, such as a "New and Natural" System of Memory. These have been, for the most part, old artificial systems, either taught intact, or subjected to slight alteration and very questionable improvement. The "New Theories" of Natural Memory also brought against Mnemonics, have frequently been nothing more than pedantic and bewildering explanations of common principles, undoubtedly known to Adam and all his rational descendants. The conduct of these impostors, who use this peculiar species of attack upon Mnemonics, is doubly mean and hateful, as it involves both plagiarism and treachery.

It has been thought by some that my mode of advocating the general claims of "Mnemonics" has been such as must prove detrimental to my personal interests, and to the protection of the public from imposition; their idea being that anybody can say he teaches "Mnemonics," and that, consequently, whatever worthless rubbish may be thrust upon the public, will, nominally, have my approval. I should be sorry if such were to be the case; but I would much prefer subjecting myself to being censured for that course of conduct, than be guilty of meanly attacking those who have done anything to further the Science. I have therefore always appeared as the advocate and defender of the Science of Mnemonics, and have made no attempt to enhance the value of my own System by detracting from the merit of that which others have propounded. In fact, as far as possible, I am the friend of every Mnemonist. This peculiarity in my mode of advocacy was noticed by the press at my first public lecture at the Royal Colosseum. The Daily Telegraph thus writes, June 19th, 1861:—"Unlike the generality of his fellow-lecturers on the Art of Memory, who impudently pretend to have made all kinds of wonderful discoveries, Mr. Stokes candidly avowed that the principles which form the foundation of his System are of very ancient date, and were, in fact, well known to the Greeks and Romans."

It is true that such was, and that such is, my mode of procedure. But the fact of my not attempting to take to myself the credit due to others, is no reason why I should passively allow others to endeavour to take the credit which is justly due to me. Having studied deeply the Mnemonical Literature of the past and present, and having in my possession a Mnemonical library, superior in many respects to that of the British Museum, I am qualified to pass an opinion, based upon practical knowledge; and I can make two assertions which can never be disproved.

First, I am teaching successfully many extremely old Mnemonical schemes, which some of the most modern writers upon the subject have declared to be useless and objectionable; and, second, I am disseminating a number of Mnemonical appliances, based upon old Mnemonical principles, but which are, in the general acceptation of the term, new and original; appliances which were not to be found in the whole range of Mnemonical Literature, anterior to the date of my introducing them. Mark, however, I do not recommend them on account of their "novelty" and "originality," but on account of their immense usefulness; and I direct attention to the combined antiquity and originality of that which I teach, in order that I may not be charged with arrogating to myself credit to which I am not entitled; and in order that I may not be robbed of hard-earned literary credit, and of current cash, by a number of ungrateful, untruthful, and unthinking literary thieves, who would claim anything, steal anything, and endeavour to undermine the professional reputation of anybody, in order to earn an honest (?) penny, and "to get their name up." The literary world has a great aversion to "stolen property," and holds its venders in supreme contempt. What, then, can be thought of those who steal, and try to show that he whom they have robbed, from them has stolen? Judging from what has been done before, it is not improbable that other editions of this book, with sufficient "improvements" to mar its utility, will shortly be issued, with other "authors"(?) names attached to my pieces of composition. A great many "writers" of Memory Books seem to have made them according to certain directions, as a cook would follow Soyer.

For the benefit of any who may aspire to similar productions, I give the following

RECEIPT TO MAKE A "MEMORY BOОК."

If you'd make a "Memory Book"

To this receipt you'd better look:

Old methods hit with all your might,

And say you've set their failings right;

Mnemonics say you don't believe in,

(And yet Mnemonics you must weave in),

Its origin you can with ease

Attribute to Simonides,

And then explain it as you please.

Stray thoughts from various authors bone,

And add some rubbish of your own;

Take some leaves from Dr. Grey—

Four, or half a dozen, say;

And twenty from Feinaigle take,

And then the whole together shake,

And thus a "Memory Book" you'll make;

And henceforth, best of all best jokes,

Pray say that you've improved on Stokes;

Have it bound, and send it out,—

And pipe-lights it will make, no doubt!

It is sometimes very difficult to tell where Natural Memory ends, and where Artificial Memory begins; and in most instances this matters but little, as it is folly to attempt to repudiate Art. The opponents of Artificial Memory appear to be most forgetful people; they forget that when they write against Art, in so doing they employ the "Art of spelling," and the "Art of writing," which would be valueless without the "Art of reading," the use of which would be circumscribed without the "Art of printing;" and that the implement they use is an Art-made pen, conducting Art-made ink to Art-made paper, produced with Art-made machinery from Art-made materials; and that they would never have perpetrated the absurdity of penning such trash, if they had been better skilled in the Art of reasoning, and had had the facts upon which to reason arranged in their mind by means of that which they endeavour to extinguish—the "Art of Memory!"

Writing is in itself a species of Artificial Memory: thus, the written word "Memory" is an Artificial combination of letters or Artificial signs, which it has been agreed by Art-using man, shall, in the English language, represent, or suggest, or bring to our Memory, that particular power or action of the mind, Artificially named "Memory."

The reasoning of the antagonists of Mnemonics is in effect this:—To bring ideas before the Memory by means of pen, ink, paper, writing, printing, and reading, is wise; but that to bring the same ideas before the Memory, without these particular auxiliaries, is folly. The philosophy of such reasoning is too profound to be at once apparent, and it must have very able expositors—which it has not had yet—before it can be for a moment tolerated by those possessed of rightly-used intelligence. The opponents of Mnemonics have been wordy, satirical, abusive, obstinate, obtuse, and vindictive, but they have not been logical!

Many men delight in the contemplation of their influence, in the knowledge of their power, but exultation in the benefits conferred upon society by the exercise of influence and power, is a delight which is nobler by far. The bitter and unmerited attacks obtuse, and vindictive, but they have not been logical! which have been made too successfully upon Mnemonics, may have gratified this love of influence; but the results, to the sensitive mind, must awaken absolute grief. Many of the cleverest men that ever took up pen have written against Mnemonics; many of the ablest men that ever engaged the public ear have spoken against it; and many of the most influential men have worked against it; yet Mnemonics is a great fact. But upon the ground of its being a great fact, some men, in the plenitude of their wisdom, would despise it. They, in the majesty of their intelligence, repudiate the recognition of facts, and deign only to pay regard to principles, to thoughts—to deal solely with thoughts, ay, factless "thoughts" (?) is that of which they are proud! To collect them, to create them, to preserve them, is their aim, their sole ambition.

The mere thoughtologist, who makes a thought his goal, and, in his haste to reach it, pauses not to look at FACTS, too often speeds to error!!! This objectionable haste, this presuming that a "thought" can be worthy which is simply based upon a "thought," has done the world much harm in reference to Mnemonics. Those who have neglected to obtain or to regard the facts upon the subject, have "thought" that Mnemonics was of very circumscribed and questionable utility, and have "thought" that thought would be injured by it; in fact they have "thought" that all thoughts which can be thought of by it are not worthy of thought! For instance, some have "thought" that Mnemonics would only apply to dates and isolated facts; and then they have "thought" that to repudiate Chronology would show wisdom, and that to ridicule the accumulation of facts, would be indicative of philosophy; but it is better to possess isolated facts, than to cherish connected fallacies—mere factless thoughts! The thoughtologists' intended attacks upon Mnemonics are, in reality, arguments in favour of its full application. That Mnemonics is of very circumscribed and questionable utility, is a factless thought. That Mnemonics is valueless in uniting facts and thoughts, in the application of principles, is a factless thought, That to assail that which we do not understand, and to despise the acquirement of that which we cannot master, is wisdom, is a factless thought; and the union of these factless thought places the THOUGHTOLOGIST upon a throne of error, upon which he can, with complacent arrogance, wield the sceptre of ignorance in the mock robes of philosophy!

Upon the scroll of fame are emblazoned the names of those who demonstrated the usefulness, and not the uselessness of the discoveries and inventions with which their Memory is associated. A writer may pride himself upon having "smashed Mnemonics all to pieces," but like the ignorant countryman who boasted of having "killed" a watch, he has achieved a very questionable victory.

The Anti-Mnemonical books upon Memory are pernicious weeds in the field of literature, which must ultimately be trodden down or uprooted by enlightened public opinion.

But let us not be content with the knowledge that Mnemonical truth will triumph some day. It is gratifying to think that posterity will reap advantage from the Mnemonical truths which we are now sowing; but why should not the present generation participate in the benefit? Posterity will not lose, but gain thereby. Arouse, my fellow countrymen! Arouse, enlightened men of all nations! Lovers of progress, I say, arouse !—arouse and share, and help to spread at once, the great, the universal boon—Mnemonics!!! Your own comfort, and the prosperity of your children depend greatly upon the adoption of the Science. The influence of Anti-Mnemonical writings has proved a curse to many a young man, and has been a drawback to many a family. Many Anti-Mnemonical writers have been good, as well as both learned and, in general matters, wise men. They have written with the purest motives that which they conscientiously believed to be true, but which is false; and thousands of laborious students, deterred from Mnemonical study, through their dent instrumentality, have worked, as it were, upon the wind, have failed at examinations through the want of the aid which Mnemonics would have afforded their labours for years have been thrown away, and their prospects in life have been blighted for ever. This is but one phase of the evils, which are almost numberless. Although clever men may sometimes write trash, and good men may sometimes unintententionally give bad advice, that is no reason why both should be accepted. Mnemonics is a great fact, and the interests of humanity demand that it should be as such regarded. The more numerous the attacks upon Mnemonics, the more formidable its antagonists, the greater the difficulties against which it has to contend, the greater the reason for unity, promptness, and unflinching perseverance on the part of those who would make known its merits.

It is never an altogether pleasing thing to have to try to prove that people are wrong in that which they think and do, and it is particularly disagreeable when the task is undertaken, not against a few, but against the world; to make statements which are thoroughly antagonistic to the general belief, without having one friend, without any support, without even any admirers, to be a kind of intellectual Ishmael, for a man to feel that he has "his hand against every man's, and every man's hand against his"—this requires a certain amount of belief in that which one advocates, in order to produce continued effort. A few years ago, the distinction I won for my-self of "The Champion of Mnemonics," was a very questionable compliment, and was as often conferred in contempt as in respect. But things have changed, and where there exists an intelligent knowledge upon the subject, I may be proud of my designation. It is not difficult for me to show that the world was comparatively ignorant of the nature and merits of Mnemonics, and altogether incredulous as to the possibility of any good ever resulting from it, when I commenced my public Mnemonic championship.

Notwithstanding the able efforts of my many talented Mnemonical predecessors, even while I write the Science is being assailed as valueless and injurious, through the press and upon the public platform, by men who ought to know, and by many who do know better.

Pertinacious adherence to uttered error is not an indication of nobleness of mind, or of greatness of intellect; some of the cleverest and most extensively appreciated writers and speakers of the day have not considered it in any way derogatory to their position to expunge, retract, and express regret at having made statements antagonistic to that which I have since proved to them to be of such worth—Mnemonics! Many of the most influential newspapers and periodicals of the day, that once attacked the System, have favoured me with their support; and the change that has taken place in public opinion generally, in reference to the subject, is very marked. In fact, I have abundant proof that my humble, but earnest and unceasing labours for years have had important effect, not simply in London, but in all all parts parts of of England, England, on on the continent, and, in fact, throughout the world!

Although the philosophy of obstinately disregarding important facts has never been fully demonstrated, there are many, who, in spite of all proofs of the efficiency of Mnemonics, seem to pride themselves in asserting that "there is nothing in it," or at least that they think "there is nothing in it," and that, if they are wrong, they are quite satisfied to re-main in error. With "Stokes on Memory, with Illustrations by Pupils," constantly before the public at the Royal Polytechnic Institution, and elsewhere, let us rejoice in the knowledge that Mnemonical sceptics and opponents are daily becoming more rare, and we will hope that the reader is not one of the number, as to all such who are especially addressed with more gravity than may at first appear, the following may seem rather insulting, although to offer an apology, which may make the matter worse, there can be no great harm in speaking the truth!

Would a man with sound brain,

Ever try to maintain,

Or would any one wish to repeat,

As he walked out at noon,

On a hot day in June,

That "the sun didn't give light and heat?"

If your eyes you will close,

And then choose to oppose,

Great facts which are clear as the day,

You can; but you're foolish,

Pig-headed, and mulish,

Which is all anybody can say!

One very clever Anti-Mnemonical thing is to say Mnemonics is not an "Art," but is only a "trick." Well, although such an assertion may appear to be somewhat detrimental to the dignity of Mnemonics, it must certainly redound greatly to the credit of the Mnemonist, for if it were really "only a trick," if there were really "nothing in it," and he can do so much with it, his achievements must undoubtedly show great skill. It has been quaintly said that "any man can thrash corn out of full sheaves, but to get a plentiful harvest out of dry stubble, is the right trick of a true workman!" Surely, if Mnemonics were a trick, it would be a "trick worth knowing!"

Wordsworth's well-known, and, in fact, rather hacknied lines, descriptive of one who was unconscious of the loveliness and suggestiveness of things around him, certainly impress us with the idea that "Peter Bell," to whom the poet alludes, must have been a type of a most pitiable portion of humanity—the unappreciative. But, in the field of literature, it is not difficult to find his parallel. Above all others, the wordy, critical, would-be-wise Anti-Mnemonist, merits this unenviable distinction. A man must be under an immense delusion who can take the trouble to try to impress others with the fact that he "can see nothing in Mnemonics." Should anybody have striven thus with the idea of gaining for himself "a name," he may, perhaps, have succeeded, but it may not be THE "name" for which he was ambitious.

Mnemonics, most suggestive flower

That Science ever bore;

The word "Mnemonics" was to him,

And it was nothing more.

The worth of it he could not tell,

This philosophic (?) "Peter Bell!"

words worth (remembering, by) stokes.

My constant appearance before the public in London, and in various parts of England, for years, having frequently delivered as many as two or three public lectures daily, independent of lessons, has brought me in contact with an immense number of the most learned, talented, and influential people of the land, whose genial welcomes and unmistakable indications of esteem will ever be gratefully cherished in my Memory.

And I cannot refrain from saying a friendly word here to my intellectual enemies, the "Anti-Mnemonists," and to strangers who are Non-Mnemonists. Let it not be thought that I have written in an unkind or ungenerous spirit. It may possibly appear to some who are not acquainted with the immense amount of apathy, rebuffs, and antagonism against which I have had to contend, that I have been unnecessarily susceptible of aggrievance. In the words of Thomas Hood, you might say of me,

"He seems like a hedgehog rolled up the wrong way,

Tormenting himself with his prickles."

But these grievances are not imaginary or self-inflicted, and the interests of the world demand that the Science of Memory should be freed from the ignominy which has been so lavishly heaped upon it. Many people would scarcely credit some of the facts which I could adduce, but which, from kindly feelings, I have refrained from publishing. I have introduced the claims of the Science to many, who, it might have been supposed, would gladly have supported it. For their indifference I am not responsible.

I write this book under very peculiar circumstances. I am not wondering whether it will ever be read, but I write with speed, knowing that there are thousands, many thousands, anxiously waiting for its appearance. There can be little doubt that, before very long, Mnemonics will be generally recognised as an established Science; and posterity will look back, and regard this "Stokes on Memory"—this plea in its behalf—as an indication of the intellectual darkness of this age of boasted enlightenment,—will laugh at the oblivious herd of Anti-Mnemonists Laug existing in the nineteenth century!

I feel more as if I were talking with my pen to a number of dear friends than "writing a book;" and with a strange feeling of reality, I seem to be in sympathetic communion with the mighty Mnemonical minds of the past, and in familiar chat with appreciative posterity.

In the foregoing work, I have given you that which I know, from practical experience, to be extremely valuable information; and, I trust, in such a manner, that, by the majority of my readers, it may be clearly comprehended. From the immense number of applications I am constantly receiving, I am convinced that something of this kind has long been required.

No less than six editions—six thousand copies of my former little treatise on Memory, have been sold. In its production I strove to combine brevity with its other characteristics; and, from abundant testimony, I am sure that, although it was remarkably brief, yet it was very useful. The matter it contained is embodied in this book, and I have made such additions as appeared to be the most desirable.

It is a general complaint of those who have bought books on Memory and Mnemonics, that they cannot understand them; and many people have assured me that the more they try, the more confused do they become. I have therefore carefully endeavoured to avoid introducing many things which might be productive of similar results.

I have, however, in compliance with numerous requests, gone into some matters, which I feel confident, to many of my readers, will not appear to be so simple or so valuable as they really are. This is no fault, either of the System, of my readers, or of myself; it merely arises from the nature of circumstances, over which we have no control.

Many very simple things are exceedingly bewildering, unless explained orally—these I teach in my Lessons; and I have frequently been told by my pupils that I have given them a better knowledge of Mnemonics, in half-an-hour, than they have previously obtained from studying books upon the subject, half their lives! Although you would undoubtedly derive infinitely greater advantage, were you to receive from me verbal instruction, yet I am confident that, if you will at once ACT upon the suggestions I have given you, you will never pass an hour without finding them of use.