Top-Notch Magazine/Volume 77/Number 2/Jungle Magic

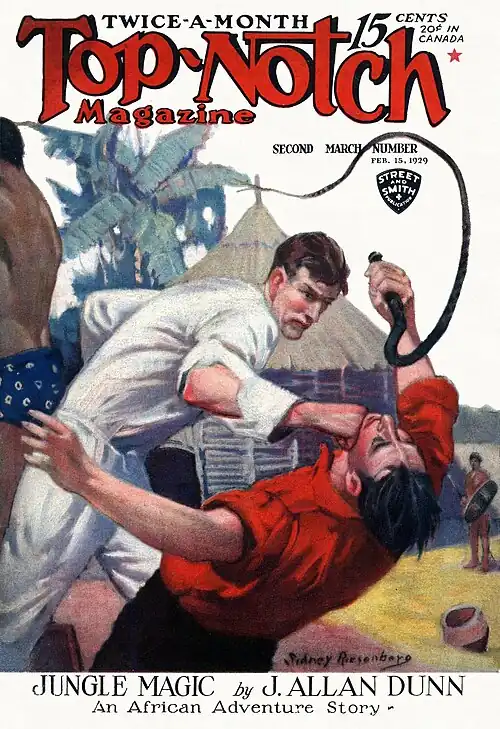

Jungle Magic

by J. Allan Dunn

A COMPLETE NOVEL

CHAPTER I.

Secret Voice of Africa.

The yacht Nautilus, of New York, Paul Collamore owner, steamed south along the western shore of equatorial Africa beneath the light of fiercely burning stars that were reflected in the long heave of the oily sea. Two miles to port lay the dark loom of the shore, black against the purple of the sky, vague and mysterious.

The land where the Congo rolled down to the ocean. The land of savagery, of elephants and gorillas. The land of Mumbo Jumbo, where the witch doctors smelled out their victims, and the dwarfs shot their poisoned arrows. The land of human sacrifice and cannibalism.

The sea ran shoreward in long, broad undulations, the ground swell of a recent gale or seismic disturbance. The swell was unbroken where the Nautilus sped smoothly, lights blazing. Music blended with gay voices and light laughter from the main saloon, where Collamore and his guests played bridge, danced a little to far-fetched radio music, jested and drank champagne.

Onboard was a rich, carefree, and reckless crowd of the owner's set, including his fiancée Claire Fordyce. The men were in tropic linen with white mess jackets, the women in light, daringly designed gowns.

Nearer land, the sea swell climbed a swiftly shallowing and irregular slope to the mangrove-fringed beach. There it charged the shore in rank upon rank of combers—curving, curling, breaking rollers.

Long lines of creaming surf, shot with sea fire, glimmered on the dark water. It was surf that even expert Kroo boys would hesitate to tackle. It set up a low thunder. To Waring, leaning on the rail, the roar seemed to be increasing in sound and momentum.

The service pantry had a door that opened on deck. Waring could hear any summons. Meantime, he watched the star blooms of the swarming protozoans, glowworms of the deep, myriads of them, bursting into phosphorescent flame.

Waring wondered why the passengers preferred to stay inside, doing things they could do anywhere, ashore.

They were missing the magic of the night, a curious emanation that seemed to be borne on the light land breeze. It was a whisper—a call in which Waring fancied he could hear the muttering throb of drums--the secret voice of Africa.

Suddenly the deck lifted, tilted under Waring's feet. The bow of the Nautilus lifted high with a jarring, staggering crash as the yacht flung itself upon a newborn reef, uncharted, upflung by the seaquake that had left the ocean still disturbed.

There was instant confusion—barked orders, the running of the crew, the passenger's crowding out on the slanting planks, the shuddering shift of the engines as the churning screws reversed. Steam and the heavy smell of hot oil came up from the engine room, the machinery was racketing. Collamore, bleating, vanished as the Nautilus listed more sharply, groaning like a wounded creature.

Now the tremendous force of the sea, through which the yacht had glided under power, made itself manifest. It was as if some slumbering monster, disturbed by an insect crawling on its hide, had lifted a lazy, but malevolent, paw to strike.

The radio operator sent out his plea for help, vibrant on the ether.

S-O-S! S-O-S! — S-O-S! Yacht Nautilus on reef!

He added the position given him by the haggard first officer. The captain was on the bridge.

Reports told of their desperate condition. Engines shifted, plates buckled, Loanda, the nearest port, far away. No ships spoken with since noon. No answer to the call of distress. Water glowing with phosphorescence began to boil about the yacht.

The swell lifted her slightly and slammed her down again. Now it was the frame that buckled. Plates carried away as the water rushed in.

Titanic, relentless blows forced the doomed ship, listing and lurching, across the treacherous ridge to deep water, while the rock fangs tore and ripped her bottom apart.

The lights went out, steam hissed as the fires died. The radio call faltered, failed. Once more the boat was lifted, flung down, grating and grinding, her back broken. The surf roared, women trembled, men were silent or shouting, fighting off panic in the serene twilight of the stars.

A girl broke her hold on a stanchion and came sliding, falling to Waring's side. Claire Fordyce, half frantic with fear, clutched at him as he checked and held her, with one arm about her slender, supple waist. She moaned in terror.

“Paul! I couldn't find you. Why don't they launch the boats? They say we're going down. Paul! Save me. I don't want to die!”

It was the strength of Waring's arm that enlightened her. Collamore's was flabby. But the two men were curiously alike in general feature and build. The resemblance had caused comment, suggested trouble.

Collamore had bought the yacht but had not seen his employees till he came aboard. He had not liked the looks of his second steward. Perhaps Waring reminded him of what he might have been if he had not gone his own way about living. He may have resented the occasional looks he had seen Claire give Waring, and then himself—comparisons.

Waring, in whites, though his jacket was of cut less swagger than that of Collamore, looked enough like the owner in the starlight to be mistaken for him by a frightened woman.

Waring told her who he was. She gazed at him blankly for a moment before she broke away. He was at his boat station. He did not know much about such matters but the surf seemed sinister. Again, Waring thought he heard the throb of drums.

Now water seethed along the port rail, so far had the yacht slanted over. It was almost impossible to launch the boats on the starboard side. The Nautilus still ground shoreward. They were swinging out the gasoline tender, under the revolvers of the officers, holding off the black crew.

Collamore was dragged along between two men, limp, nerveless, whimpering. The ray of an electric torch showed his craven face. The girl was with them, but Collamore did not notice her.

Waring's boat was almost ready. There was a surge of firemen, armed with metal bars, one of them down, shot, the rest swarming on the falls, leaping into the boat. A fall rope snarled, the other ran out, tipping them into the sea in the smother of foam.

A mass of water rammed the ship, pitched it forward free of the reef. The sinking ship crushed the launch and the boats. The struggling men, thrashed about and some sank, with bubbling cries.

Waring dived clear and deep and came up at last on the crest of a giant comber that rushed him forward. Driving overhand.through the smother, he was flung farther on as another seething roller caught up with him.

Waring could swim! He should make shore if the surf gave him a chance. It was sporting with him, slapping beneath the surface, rolling him, giving him small chance to strip, though he managed, at last, to get rid of coat and shirt and trousers, down to his B. V. Ds.

Forced to constant battle, Waring could not get at his shoes, canvas with rubber soles, and was glad of it later. Sometimes he rode on a crest, but it took furious energy to gain the right position. He saw that he was going to need all his strength.

Waring could see nothing of any survivors. There was only the suck and tug and fling of the combers, the savage roar of it all with, now and then, a glimpse of the dark, distant shore. A strong current was bearing him down, but the tide was with him. If it had been ebbing, he could never have made it. He was not sure now, but he hung on grimly. He feared the tremendous pull of the undertow when he finally hit bottom and started to wade ashore.

If he ever did.

Waring saw a V-shaped trail of sea fire back of the dorsal fin of a shark in the trough ahead of him. He could see the great body of the brute, vaguely outlined, shrouded in a veil of phosphorescence. The sea wolves were gathering to the feast, brought by instinct, as buzzards come to carrion.

The tepid waves seemed suddenly to change to ice water. Waring's blood ran cold, his limbs were leaden. He was being swept down toward the hungry devil, who waited for him, poised. Something rapped his shoulder. This was the end

It was a pontoon raft, part of the yacht's life-saving equipment, riding buoyantly, untenanted, undamaged.

He snatched at the nearer cylinder, but failed to get a hold on the rounded surface. Then, as it passed him, Waring put all he had into a desperate crawl down the sloping hill of water. He caught at the platform, kicked down hard as he saw the shark rising, turning, with shovel nose, cold eyes and open maw.

Half-vaulting, hauling on a rope cleat, Waring slid aboard, almost exhausted. The light raft reeled with a blow. The shark, baffled, darted off in a green glow that vanished in the depths. Waring clung to the rope loops along the coaming of his bucking craft.

Now he looked back and saw nothing but the raging ranks of water. There was no sign of the yacht, of any boat or other raft. Waring saw one swimmer as he lifted on a swell. Even as he gazed, the man flung up his arms as he was dragged under, his shrieks coming faintly to Waring.

There were other fins now, scything the surface as the beasts ranged for more food, but Waring was safe—for the present. Each successive surge hurled the raft shoreward. What he might find on that savage shore where the drums had muttered, Waring could not guess, hardly dared imagine.

He was going to stick it out to the last. There was no light showing, nothing but a mass of dense, dark bush and trees. Beyond was the indistinct suggestion of a mountain range.

A strip of beach showed in a long crescent. A great wave came rearing, lambent gleams in its crest. It curled above the raft and came crashing down.

Waring was swept from his hold, whirled about so that he lost all direction. He struck out and hit the bottom, fought on until his lungs seemed on fire, weakening, striving not to take the gulp that would fill them with water, drown him.

Spent, Waring found the surface, gasped, and got air before he was battered under again. He was in the shallows now, the water boiling with sand and grit. He was rolled like a log in rapids, finding bottom, only to be swept off his feet, drawn back by the terrific force of the undertow.

He struggled on hands and knees, fingers and toes deep in the sliding shingle, until a frightful blow between the shoulders pounded him flat. At last, Waring was spewed up, senseless, to lie on the verge of the tide that was changing to slack.

The steady stars burned on, the constellations wheeling. Then, without warning, the sky seemed to shake like a curtain and the stars vanished as the sudden tropic dawn flamed from behind the distant range. The jungle took on color and life. Doves cooed and parrots screamed with sudden flights, their vivid plumage gleaming like scraps of rainbows.

Waring lay, half-naked, on his back, arms upflung, sole survivor of the wreck.

CHAPTER II.

Jetsam.

Five men came along the beach, four of them with skins plum-black, scarred with tribal wheals; wearing kilts of trade cloth, their hair frizzy, their teeth filed to points between blubbery lips.

The fifth was saddle-colored. He wore a turban and a short jacket. There was a sheathed knife at his belt, sandals on his feet. His features were not flat, like the others, but suggested Arabic blood. He was the leader of the party, looking for wreckage and loot, their eyes greedy, their faces ghoulish.

So far they had found nothing but broken planks. The scavengers of the sea, the sharks, had gleaned their harvest. The sunken yacht still held its stores. The leader indicated the promontory as the turning point of their search. One of the black men gabbled, his hand pointing to the limp body lying between low hummocks of sand, half-hidden.

The saddle-colored man stirred Waring with his foot, contemptuously, believing him dead. There was nothing on him to take. The leader covertly hated all whites, though he feared them. Then Waring stirred, groaned, and opened his eyes, to close them again, worn out with his fight against the surf.

His dull senses refused to register the sight of the faces staring down as anything but the phantoms of a nightmare. His flesh was bruised and torn, scraped badly in places by the grit, but his heart beat strongly. He was coming back.

The leader hesitated and then gave an order. Two of the black men picked up Waring and carried him, unceremoniously, by his legs and arms, as if he were a bundle of no particular value. They had hoped to pilfer on their own account, and they were sullen.

A mile down the beach, they turned off into a trail between the mangroves that lined the oozy banks of a sluggish, creek. Soon, the blacks came into a clearing, where there were several buildings all covered with corrugated iron, a dwelling, cabins, two warehouses and, back of a stout, high palisade, behind heavy gates, a barracoon.

It was the trading station of Pedro Gomez, Portuguese, dealer in ivory, slaves, and tusks; in ivory nuts and rubber. Gomez had, also, a rubber plantation. The rows of rubber trees showed in the background of the clearing.

From the barracoon came the sound of droning song, the smell of cooking. Laborers were busy on the plantation. A group of Bantu in skin kaross squatted beside their canoe at the landing, spears in the hollows of their arms, long knives at their sides. Their chief wore a leopard skin across his shoulders, and carried a carved club of authority, a sort of scimitar, across his knees.

The Bantu stared curiously at the little procession that went on to the trader's house, where women hunkered down on the veranda, clad in sleeveless cotton prints. The women were of all shades from light coffee to black; of all ages, from fourteen to forty. They rose, jabbering, as Waring was borne up the steps. Gomez came to the door, a sjambok of rhinoceros hide in his hand with which he threatened them. They became silent.

Gomez was in creased and grimy pajamas, native sandals on his feet, his upper garment open to show a shock of black hair. He was squat, swarthy, corpulent, and double-chinned. The crisp and tightly curling fringe of hair about his bald skull top, hinted of blood darker than Moorish in his veins. His eyes were small, piggish, and bloodshot from overnight drinking.

Gomez listened to the leader's tale, scowling. He ordered Waring taken inside, and sent the men back again for a more extended search. Then he sat down again to his breakfast, waited on by two Bantus in ragged shorts of striped canvas.

He paid no attention to the half-drowned, half-senseless man, who lay on a cot in a back room, without even a mosquito net over him. Bolting and gulping his food, his low forehead wrinkled, Gomez considered the one thing worth while to him: What could be made out of this stranger, cast up on the beach?

Waring came to, weary, thirsty and hungry. He turned his eyes toward Gomez as the latter entered. Gomez spoke in a language Waring could not understand, though he fancied it might be Spanish.

Waring managed a faint—“No sabe. Agua!” His tongue was swollen, his throat parched.

Gomez grunted. “Ingles?” he asked.

Waring shook his head. “Americano. Yacht wrecked last night. Nautilus.”

Waring saw a gleam in Gomez's eyes at the last word. The trader nodded, went out. Soon a Bantu boy came in, grinning, with a tray of food and a gourd of water. Another followed with some clothing, extra pajamas of Gomez. The Bantu boys were both good-natured, like trained apes, their eyes rolling, shifting, their mouths ready for loose laughter.

Waring made them understand, pointing to his wounded places, that he wanted more water. One of them fetched a jug and basin, and a rough towel. They watched Waring as he washed and ate and put on the pajamas that were grotesque on his tall body. They slapped their thighs and roared with guffaws, at the lack of fit.

There was no further sign of Gomez. Apparently, Waring was going to be fairly well treated, but he did not trust the trader. The man was at once furtive and possessive. Waring sensed that he was regarded as something to be made use of. There was a certain cruelty of calculation in the trader's gaze that suggested that he would not be very hospitable if he saw no signs of gain.

Waring felt refreshed and strengthened. He began to conjure up what he knew of the west coast of Africa from more or less desultory reading. This must be Angola, south of the Kongo, thinly populated along the coast by Portuguese.

It was a wild region, inhabited by savage natives, and nominally under control of Portugal. But in reality, it was ruled by native chiefs of warlike tendencies, who were placated by trade. The natives were a fierce and primitive race sunk in the ancient superstition of the jungle.

Waring had learned aboard the Nautilus that there was no American consul at Loanda, no representatives of the United States in Africa except at Cape Town, Durban, Port Elizabeth, Johannesburg and Nairobi, all far away. The party on the yacht had intended to stop at the first and last, going up to Nairobi and the big-game country by railroad from Mombasa in British East Africa.

Waring was a stranger in a strange land, penniless, dependent upon the aid of what white men he might meet who would help him out. He did not think that Gomez was white. There was a stroke of the tarbrush in his ancestry, unless Waring was much mistaken. Here, Gomez was a despot, and the position had developed the worst traits in his nature.

Waring had nothing to offer him. No funds upon which he could draw, none to whom he could apply for money, unless it was a consul, a long and doubtful process.

It did not take Waring long to take stock of the assets of his position and the result was not encouraging. In the end he shrugged his shoulders. Gomez might be better than he seemed. Or the trader might find some work for him, and let him pay his way out of the situation.

After all it was adventure. One must not expect adventure to always wear a bright face. Dangers beckoned, but there were unpleasant things to be encountered, made part of the reckoning. It was adventure that caused him to answer the advertisement and persuade the head steward of the Nautilus to take him on as second for the long voyage contemplated. A chance to see the world—not entirely through a porthole—a trip to be limited only by the whims of Collamore and, less likely, the wishes of his guests.

Waring had been at loose ends. While there were other methods of making a living, this had appealed to him. There had been the somewhat unpleasant incidents arising from his likeness to Collamore. It had begun to look as if he might not last the trip.

Collamore was spoiled, by circumstance and a certain unpleasant ferment in his own make-up. Waring had sensed that he was not in favor, though he had given no cause for fault. Collamore was dead now, with all his guests and employees—save Waring—and here was Waring surely upon the threshold of adventure.

Even as he had felt the call of the savage coast from the yacht's rail, the lure of its mystery, so he still felt something of it in the present atmosphere, despite the untidy room in the trader's house.

If he was in present peril, it was surely a minor one. He was a person of slight importance, but, after all, he was a white man, young and healthy and not weak of will. It would be hard if he could not make something out of it all.

Waring went through the front room, littered with samples of trade, with saddles, guns on trophies of horn, canoe paddles, simple furniture offset with skins on the floor and walls, hides of lions, zebras, spotted cats, bucks, the stuffed head of a two-horned white rhinoceros, native weapons, shields, a carved drum with a hideous fetish god in one corner.

Collections gathered idly, no doubt, tribute from native chiefs. All little side lights on the Dark Continent, that gave Waring a thrill as he examined them. Through the dirty window he could see the women goggling and giggling at him, suddenly silent as he went out on the veranda.

The compound was vacant save for chickens, a goat, and two dogs, like German police hounds, that snarled at him and would not come to him, both stoutly chained. There was a post in the middle of the place that had cross arms to which straps were attached, a block at its foot—a pillory or whipping post. Flies buzzed about it. It was a white man's fetish of power and cruelty.

The droning chants still came from the barracoon. A great baobab sprawled over the ground opposite the house, and lean pigs lay in the shade. In the rubber plantation the laborers were watched by men with whips. The place was neither orderly nor disorderly.

Waring considered it probably profitable. The hand of the white man had reached out and gripped produce and people, with fingers cased in iron, with no glove of velvet to mask the gauntlet.

CHAPTER III.

War Drums.

Gomez came out of the biggest warehouse, walking with a strut, carrying his inevitable sjambok. A pickaninny ran too close to him and he snapped the lash at the child who ran off yelling, crimson streaming from his bare buttocks where the tip of the terrible rhinoceros whip had flicked out flesh.

Waring's dislike of the man changed to hatred. His fists clenched, but he restrained himself. He had taken in the fact that he was a prisoner, if Gomez so chose. Beyond the belt of trees lay the ocean, all about was the jungle and the barbaric natives—the wild brutes, dangerous as sharks to an unarmed man,

Waring was between the devil and the deep sea, literally. And he believed that, if Gomez was not in league with the former, he was not far from it.

Gomez grinned as he saw Waring swaddled in his pajamas. It was a derisive grin yet his manner was, if still calculating, distinctly more pleasant.

“Soon Ingles come,” Gomez said. “I send. Soon, I get sometheeng for you not so bad.” He pointed at the ill-fitting garments.

Waring did not want anything from Gomez. He was beginning to feel an abhorrence for him, as he might feel toward a venomous reptile. He did not even want a pipe and tobacco, though he craved a smoke as Gomez rolled himself a cigarito of black weed, without offering any to Waring.

Not even food. Waring might earn these things but he did not want to be under obligations to Gomez. He would rather have stayed on the beach, save for the announcement that an Englishman was coming, though what sort of an Englishman would be living, by choice apparently, in that Portuguese colony, was a question.

A horn blared somewhere and Gomez turned abruptly, striking at a native gong that hung in the veranda. Men came hurrying, overseers, from their extra clothing, their belts and weapons. The horn blew again. A melancholy procession filed out of the jungle trail at the back of the clearing.

From collar to collar stretched the links of a lengthy chain of bondage—men, women and children, many babes in arms, a forlorn collection of limping, half-starved humanity, fettered of wrist and ankle and neck. Their eyes were dull as the line came to a halt under the shouts of their drivers and sellers, one or two black, the rest typical Arabs of full or partial blood, carrying guns. Great Soudanese cracked sjamboks and wheals already showed on backs, where shoulder blades and spinal verterbrae matched the protruding ribs.

Gomez joined an Arab, others gathered round. Boys came running with palm toddy. The slave caravan stood jaded, panting for the water that was denied them. Two benches were brought. The boys held big umbrellas over the heads of the principals of the informal market. The slaves were marched past for Gomez's inspection, the whips forcing them to some semblance of sprightliness.

Waring went inside, sick at the spectacle. He could do nothing. He heard the rising voices of the chafferers, proclaiming their wares.

The dealing took three hours. The victims of the traffic broiled and drooped in the sun. At last they were marched into the barracoon, their neck chains taken off, manacles loosened. They were fed a mess of mealies and Kaffir corn.

The Arabs took up quarters under the baobab, dispersing the pigs. A fire was lighted, and the hind-quarters of a bullock brought to them with other food, and more of the palm toddy, which their faith did not make them forswear.

Gomez came into the house without noticing Waring, bringing the two dogs with him, unleashed. They did not snarl this time at Waring, but they watched him. He felt that if he tried to leave the room they would be at his throat.

Gomez took a bottle from a cupboard, set it down with a glass which he rapidly filled and emptied, twice. The reek of brandy came to Waring as the trader rolled a cigarito and sat down, seemingly well satisfied with his bargain.

Presently, Gomez began to droop and snore, his mouth open. The two dogs watched Waring. The tropic day was closing. A red glare showed through the seaward trees and flooded the sky over the ocean. Laborers came in to their quarters wearily, many striped with blows.

Two men with rifles walked sentry outside the gate of the barracoon. On top of the palisade, iron baskets flared, with pitchwood for fuel. A central fire illuminated the compound. The women had gone. Twice, Bantu boys looked in the door and tiptoed off as the dogs growled deep in their throats.

A big man, bearded, in white clothes, with a solar helmet, came riding in on a mule, a Kaffir trotting behind in the dust like a hound. This, thought, Waring, should be the Englishman, and either his servant or the messenger Gomez had dispatched.

The man dismounted heavily—glanced at the Arabs and came up the steps, filling a pipe. The Kaffir vanished.

It was dark in the room. The Englishman stopped in the doorway, looking in. The dogs set up a furious barking, but made no effort to attack the man, acting as if the hatred they held for him was tempered by a fear of Gomez' rhinoceros whip.

Gomez awakened instantly, and sprang to his feet with wonderful agility for his bulk, a gun coming into his hand from a shoulder holster. Here was a man, Waring thought, who, for all his mastery, lived in constant dread of attack. It explained the two dogs, carefully trained to tell Gomez's friends and foes apart.

Gomez shouted. The Bantu boys who had been waiting his pleasure came cringing in. They dodged his kicks as they lighted lamps, and scurried about to other orders given in their own language.

The Englishman laughed, and lighted his pipe. Waring stood up, feeling ridiculous in Gomez's clothes. The bearded man gave him a nod and then ignored him, talking to Gomez in Portuguese with a pronounced British accent. Once more Waring felt himself a chattel.

The Englishman took off his helmet and lay it on the war drum. He was not as bald as Gomez, but his reddish hair was thinning out above a high forehead. His nose was well shaped, aggressive; his eyes, faded blue. As he stood profiled to a lamp, Waring saw that his chin beneath the beard was weak, receding. The lips were full and indulgent. There were bags under his eyes. Through the deep tan of his skin, broken veins of red and blue showed like the thread inserts in currency notes.

A man of good breeding, of education, fallen farther than Gomez. A man who drank his liquor slowly, as if he loved the taste of it, his hands trembling a little. A man debased, the black sheep of a family that had shipped him to South Africa as a remittance man. A man who had been rejected by his own race and found final refuge on foreign soil, consorting with comparatively ignorant traders of Gomez's type.

Yet, with advancing years, though deteriorating in body and morals, he had acquired a blend of shiftiness and cleverness that was the belated fruit of his abused brain. Gomez deferred to him in a measure, respecting certain qualities in him he lacked himself, not quite able to use him as a tool.

There was some strand of fine fiber about the Britisher that had not rot, as yet, which Gomez recognized. It showed in the attitude of the two men. Gomez was coarse and cunning, the other retained some show of breeding and, while unscrupulous, was clever. They were well-mated rogues, Waring thought. Come together because of him, though he could not understand their interest.

Gomez addressed his visitor as Senhor Hawtrey, a little irony stressed in the title, asking him why he had not been able to come earlier.

“That Kaffir of yours, Jim,” said Hawtrey, in easy, slipshod Portuguese, “found a juju on the trail and went the long way round. Swore it was set for him. I made him come back past it. Just a chicken bone tied up in a rag, but you know what those beggars are.”

“I'll have that nonsense thrashed out of him to-morrow,” said Gomez. “Did you bring the paper?”

“I've got-it. Get him out of here, what? Does he talk Portuguese?”

“I'm not sure how much he sabes,” said Gomez. “He spoke a few words of Spanish.”

“Ah!” Hawtrey turned to Waring. “Look here, my dear chap, Gomez and I want to talk a few things over. Undisturbed, and all that, while they're getting chow. You don't mind?”

His clipped syllables and broad A's were, to Waring, like those of the conventional stage Englishman, but he sensed that this was the real article. This man who might have been a gentleman, but was a blackguard in all but education and manners. He was shallow, unscrupulous, and insincere, his politeness a pose.

“Name's Hawtrey,” he said. “Geoffrey Hawtrey. Glad to meet you.” He held out a nervous, puffy hand that still had some grip in it. Waring took it, on his guard. He could not place his danger, but mind and body joined in the warning, the hunch, that these two were plotting something against him.

If Gomez had an idea of selling him as a slave—and Waring believed him quite capable of it—he would hardly have consulted Hawtrey, who would surely claim his share in any deal in which he shared.

Waring said nothing as he released Hawtrey's hand. He went into the back room, which was quite dark, since there was no fire at the rear of the house where the jungle came up closely. The place was used partly as a store-room. There were bales and boxes against the walls, probably trading goods, and the window was barred against pilferers.

It made a good prison as well. Hawtrey closed the door after Waring, turning the key in the lock.

Waring sat on the cot, resentment simmering within him, offset by the necessity of keeping cool. Mosquitoes buzzed viciously. He had no matches, no means of light. The window was unscreened. He slapped at the pests, wishing he had a smoke.

Now, once more, Waring heard the throb of drums, deep in the bush. Their pounding rhythm, distant but emphatic, seemed gradually to fill the room with vibrations that began to possess him, to dominate his pulse beats to rouse within him a latent savagery, to heat his growing anger to boiling point, beyond control.

He felt an urge to batter at the closed door, to get through, snatch a weapon, demand freedom. It was ridiculous, barabric, and impractical, as his reason whispered, but the emotional demand was insistent.

It was the voice of Africa—calling—calling!

CHAPTER IV.

A Warrior.

The door opened and Hawtrey entered, bland, carrying a lamp he set down. Waring caught a glimpse of Gomez, glancing in, of the busy Batu boys setting the table for a meal. Then Hawtrey closed the door.

Hawtrey seated himself on a box, drew out a cigar case, offering it.

“Cheroots. A bit rank but the best available. Have to get you some togs. I've got a native woman who is handy with a machine. Makes up mine. Soon fix you up. Gomez isn't much on conventions. He's a bit of a hard case. You've probably seen that. But I'll see you're treated decently while things are arranged. Not much like your yacht. Rotten luck that. Gomez thinks it's good luck for him. I'm afraid you'll have to make the best of it. I'll ameliorate conditions all I can, Collamore.”

Collamore! There was the answer. They took him for Collamore. How did they know the name? Boat wreckage might have borne the name of the yacht. But Hawtrey's smile showed hidden knowledge they meant to use. Collamore—millionaire—was very different from John Waring, second steward. He might gain decent treatment if he posed as Collamore, get clear, perhaps—but not without payment. He was not going to pretend that he was any one else but himself.

“You're making a mistake,” he said. “My name's Waring. I don't know how you heard about Collamore. But I was second steward on the yacht. I am afraid I am the only survivor.”

Hawtrey took it smiling. A sly look came into his eyes. Clearly he believed that Waring had lied. He had guessed Gomez's plan, in which Hawtrey was now a partner, called in, not merely as interpreter, but because he could better carry on the necessary negotiations.

Gomez needed also his brain. The trader could handle blacks but not high-class whites. This chap who pretended he was only a steward was a keen beggar. He probably understood Portuguese, or Spanish, enough to guess what they were up to. Listened at the door, probably. It was stout but the climate had warped it. There was space by the hinges.

“We're not so benighted here,” Hawtrey said. “I get a few papers. Here's one of them. I keep them, you see, to mull over.”

Waring looked at the sheet. There was an account of the proposed voyage, a list of the passengers, a picture of Collamore and of his fiancée, And the photograph looked exactly as Waring would look if he was shaved, dressed properly. The resemblance was undeniable. To Hawtrey and Gomez it was convincing. No explanation was available. He was Collamore, so far as they were concerned.

“You see, my dear chap,” Hawtrey went on, “we have inside information. And it really won't pay you to make out you're a second steward by some other name. It won't wash.

“A second steward would be a horse of quite another color—quite—a sorry crock, at that. Gomez has taken you in, what? He's not an hospitable chap at any time, a bit of a grinder. You twig? He'd cut up rough if he thought you'd taken him in. Apt to be nasty.

“You're really in a tight hole. As Collamore, he would treat you well enough, you have my word on that. Naturally, he would expect remuneration for his trouble. He's not running an inn, you know. Just a trading station, with slave quarters and all that, recognized by the Portuguese government, quite in favor with the local powers-that-be. In with the chiefs.

“You'll find it a bit hard to get away, rigged as you are, no weapons. You may be kept incommunicado as Warner, or whatever name you mentioned just now. No chance in the world of getting out of it. There's the jungle and the Kongo natives, not to mention the dwarfs. Cannibals and all that. Respect a white man when he's top dog only.

“No use rubbin' it in or I'd remind you of the wild beasts. There's the sea. No boats call here except trade friends of Gomez. You wouldn't get to them. If you got away on land you'd either jolly well perish or be brought back by the natives.

“In fact, Collamore, you're in a deuce of a hole, old chap. You're worth plenty. The loss of your yacht won't scratch you, financially, outside of the insurance. It was a terrible calamity, of course, but you're saved and were talking business now.

“Every man for himself, what? Gomez is putting it at a reasonable figure. A hundred thousand dollars. That's the price—at present. I'll handle it, with you. Draft on your bankers and no questions asked. Of course, I shall get my commission out of it—from Gomez. Otherwise” He tamped down his pipe, applied another match.

“Better think it over, Collamore.”

“I'll tell you what I think now,” said Waring evenly, restraining a desire to punch the Englishman on the jaw, watching the point below the beard even now, his eyes blazing. “If I were Collamore, which I am not, I wouldn't give either of you a red cent. You're white—as to skin. Gomez is a mongrel. You are a pair of unprincipled scoundrels. I think you use the word 'blackguard' in your country, or rather, what was your country.

Hawtrey laughed.

“I'll use one of your own native colloquialisms, Collamore. I had a ranch in the States once. Them is harsh words, Collamore. You're not going to come it over us that you are a second steward. You don't look like one and you don't act like one. Too much choice of language and too much spunk. I'll give you that.

“But don't let it get you into trouble, Collamore, don't let it get you into trouble. Gomez is a nasty devil when he's crossed. As for me—I've been called a blackguard before. The price of your freedom goes up ten thousand dollars a day. Think it over, my dear chap, think it over.”

There was nothing much to think about along the line Hawtrey suggested. Waring was in the toils. There must be some way out of them. Some way!

They were not going to starve him, it seemed. After an hour the door opened and Hawtrey came back with the same Kaffir behind him, this time bearing dishes that gave out a savory smell.

“Jim here is going to be your valet,” said Hawtrey. “Gomez is inclined to be unpleasant, but I smoothed him down a bit. I'll send you some togs and smoking. Jim here talks a little English. I wouldn't call him your jailer. You are to have the run of the place. But I wouldn't try to bolt. I really wouldn't. I fancy the extra ten thousand a day smoothed Gomez's hackles down. I'll run over every day or so. Good night, old chap.”

Waring looked longingly at Hawtrey's jaw again. But it wouldn't do. He caught a gleam in the Kaffir's eyes that suggested he was in much the same frame of mind. He might make an ally of Jim. If he were a Kaffir, he did not belong this far north. He was probably a slave of Gomez. He was deft enough as he set the dishes out.

“I bring muskita net,” he said. “Bring sheet.”

“Thanks, Jim.” The Kaffir looked at him, surprised at the friendly tone. He was well built, emaciated but well-muscled. There were scars on his body, which was clad in a kaross, an apron of mangy lionskin. He was deferential but not humble.

Waring could imagine him a good man in his own right. A warrior. But he was not going to press things too far. The ten thousand a day might mount up without his concern while he planned escape, by sea or through the jungle. He was not going to be cooped up.

Eventually Gomez might try to make a plantation hand out of him, when he found there was no money coming. He might do worse than that. Gomez was capable of anything.

Waring ate with appetite. Now he had no compunctions about accepting foods, cheroots, clothing. There was a score against these amateur bandits seeking to make capital of misfortune. He managed to sleep well enough under the netting, though now and then he woke to hear the drums, throbbing in the night. They might deepen Hawtrey's warning but there was invitation in them, a challenge. He was in desperate straits but his spirit was roused. Better the jungle than the barracoon.

The door had not been locked, but once Waring heard the deep growl of a dog. Gomez would rely on the dogs to guard him, trail him, aside from his native allies. But they were not going to hold him.

Gomez was at a late breakfast after Waring finished his and went into the outer room. The Portuguese glowered at him, but said nothing, even when Waring strolled on to the veranda. The two dogs got up and followed him. When he halted, they did. If he sat down, they lay watching him with red tongues sliding in and out over white fangs, dripping moisture in the damp heat. They were eyed like wolves.

Otherwise Waring was not interfered with. He walked about, watching the life on the plantation, seeing a canoe load of ivory nuts arrive with Kongo paddlers. Gomez bartered with them but he did not bully them. They were free men and fighters, amiable now but fierce of aspect. Outside of them Gomez ruled, with the lash, with fetters.

An hour before noon Gomez mounted a mule and rode off, leaving the dogs.

Waring fancied he had gone to see Hawtrey. Jim brought him a meal, served in the back room with the barred window. The dogs barred the door. While he was in the outer room they watched his every move, hostile. He looked longingly at the native weapons, the guns. But he dared not try to take one—yet.

Jim seemed troubled. He held his head high but his eyes showed it.

“Anything wrong?” Waring asked him. The Kaffir once more eyed him earnestly.

“You buccra, you white man,” he said. “Some buccra good, some bad. Hawtrey bad. Gomez no proper buccra. I am black but I am a man.” He stood up proudly swelling his chest. “I think you and me all same this place. Not belong here.”

“How did you happen to get here, Jim?”

The Kaffir squatted with a glance out of the window, into the outer room through the open door where the dogs lay on the threshold, watching with evil eyes. He spoke in a low tone.

“I am Mpondo. My name Seole. In my kraal I am free man, son of chief. I am fighting man”—he touched the ring of hair on his scalp, gummed and solid, looking like ebony. “I have killed. This also I killed—with a spear”—he fingered the lion skin of his apron. “And I am hunter. I go with white man who talked as you talk. From Meriki, beyond the wide water. Elephants and lions we killed; we sought ivory.

“His name is Tilimani in your tongue. We had another name for him for he was brave and wise. Monzemabemke. 'He who thinks as he fights.' We went through Tanganyika to Katanga and there we become sick. Black-water fever. I was his chief of safari. While we are ill the bearers go. Another white man comes and takes Tilimani. Me, he leaves because they think I will die. Tilimani does not know this. He is close to death.

“If he lives he will come back for me but he will not find me. I was still ill when slavers come. They sell me to Gomez, who treats me like a dog. To-day I am to be whipped like a dog because these Kongo people hate me. They make magic against me and I go round it, so that Hawtrey comes late.”

“They won't whip you if I can help it, Jim,” said Waring.

“I know that,” he said simply. “But you cannot help. I—if I had a knife—I would slay or be slain. Some day Tilimani will come and we will show these dogs!”

Tilimani's showing up looked like a long shot to Waring but he did not say so. Unless long shots turned up for him he was up against the wall—the jungle wall and the well of the sea.

“I go now,” said Seole, whose white name was Jim.

CHAPTER V.

Jungle Punishment.

A half-caste overseer stood in the doorway. The same man who had ordered the blacks to pick up Waring. Behind him were the same four, used as a sort of police by Gomez, official punishers. They did not offer to come through the door. The dogs faced them. Outside they would not bother them, unless so ordered by Gomez.

Seole went out with his head up and the four seized him, marched him off. Waring followed and the dogs trailed him. The Kaffir was mounted on the block, his wrists strapped to the cross piece. The half-caste swung his whip and brought it down.

A gray wheal rose instantly and he leaped to the other side of the low block, his face lit with malicious delight and crossed the second lash so that the skin broke. Seole did not even quiver. Waring stood impotent, the dogs at his heels.

At the tenth lash, Waring broke restraint. The overseer was deliberately making the worst of the whipping, trying to cut Seole's flesh to ribbons. He showed no signs of stopping.

Words were wasted, not to be understood. Waring sprang and grasped the uplifted arm of the half-caste, setting one hand behind the elbow and just above it, twisting the forearm back. The overseer let out a yell of surprise as he twisted his slippery arm loose and launched a whistling slash at the white man. Waring got in under the slash with a jolt to the liver and another over the heart that sent the man staggering back.

Waring expected the dogs upon him, but they did not offer to touch him. Their positive orders seemed to fill their limit of understanding. They did not like the blacks or the overseer. The blacks stood with slack jaws, perhaps with some concealed enjoyment at seeing their overseer in trouble. Their eyes rolled as he swung the lash again. Waring grabbed it close to the handle, wrenched it loose and flung it away.

The half-caste's knife came out, curving, double-edged and murderous. He meant to kill. Waring ducked and jarred him with a chop to his injured elbow, side-stepped a rush, and got home to the place where the ribs part, fair on the plexus. There were tough muscles there but it left the Arab gasping. The next smash did the trick, a hard, short blow to the jaw.

The overseer fell like a length of dropped chain. Waring got his knife and retrieved the whip, then ordering the blacks with imperative gestures to free Seole. It was the white man's will, the white man's conquering spirit, and they obeyed automatically.

Seole's face was gray with pain. The end of the lash had wound about him and cut into his chest.

“I thank,” he gasped. “Not forget. But I think no good.”

Gomez and Hawtrey were riding in. They spurred their mules and came up, the features of the Portuguese livid with rage.

“Tell him,” said Waring to the Englishman, “that this chap is a butcher. Look at that man's back.”

Hawtrey inspected it coolly enough, but his eyes warmed as they traveled from the prostrate half-caste, still out, to Waring, knife and whip in hand.

“You knocked him out? With your bare fists? I thought you were fairly fit, if you are a millionaire. By Jove, Collamore, I'd give ten quid not to have missed it!”

“Tell him,” said Waring, watching Gomez's gun hand hovering near his breast, “that if Jim gets whipped again you'll not get a cent.”

Hawtrey grinned, his stained teeth showing through his beard. The inbred sportsman in him favored Waring for the moment. But the grin was from another source. He thought the American had given himself away, shown that he was Collamore.

He did not play much poker, did not see that Waring had run a bluff, for the sake of Seole, whom he had been careful to call Jim. Hawtrey spoke swiftly to Gomez and the Portuguese nodded, greed in his eyes now.

“He won't be whipped, unless he misbehaves,” said Hawtrey. “Whip's the only thing these beggars understand. You ready to fix things up, Collamore? I've brought you some duds, by the way. You look like a fighting scarecrow.”

Waring made a mask of his face.

“No,” he replied curtly.

“Suits us, in a way. I could use some ready, but the price is ten thousand better than it was last night. And still risin'. What? Here.” He tossed a bundle of clothing to Seole who took them and went to the veranda. Gomez and Hawtrey bent over the fallen half-caste, Gomez kicking him in the ribs heavily.

“We'll have to ask for the lethal weapons, Collamore,” said Hawtrey. “You are jolly well too dangerous. Sorry. I could have given you a few rounds once,” he added. “Too many fleshpots—too much liquor—too long in the tropics. But I should like to have seen that fight.”

Waring walked off, the dogs with him.

“Baas!” said Seole. “Unkosi! I shall not forget.”

“Better let me fix up those cuts, Seole.”

“They are nothing, unkosi. See where the claws of the lion went. I can heal these easier. My blood is strong.”

There was a mark like a brand on his left shoulder, where claws had scored deep. They went inside together.

“I will be your blood brother,” said Seole, when they were alone. “I take your name and I give you mine, Waringi. Only to call me Jim, as Tilimani called me, whom I loved.”

“Jim and John, then. But we must fix up those cuts a bit. Turn round.”

It was the fourth day, forty thousand dollars more of ransom that could not be paid added to the set price of release. Seole had disappeared. Hawtrey could, or would give no information. He hinted that Seole had been sent somewhere, for the sake of discipline. But he had not been whipped. A half-witted Bantu boy took his place to wait on Waring.

Waring missed the Kaffir more than he had ever imagined he could miss a black man. Seole was all a real man. Waring had planned that, somehow, they would get away together. Now he would have to go, alone.

Catastrophe had come that afternoon. Waring had tried to make friends with the dogs, to no avail. He had been watched closely, he knew, ever since the fight. There were many there who would be glad of a chance to put him out of the way. Hawtrey had warned him. And now, Hawtrey had told him where he stood.

The launch had got ashore, after all, flung up like a broken crate. In it was found what was left of Collamore. Enough to establish his identity.

“Not your fault, Waring,” said the Englishman, his face serious, not unfriendly. “You told the truth except when you fooled us over Jim. But you're not Collamore, you see. And Gomez has you. I don't know what he has in mind but, if I were you, I'd knuckle down.

“I know you're not the sort to do it, but this is a friendly tip. I've done what I can. I'm deep in to Gomez. He could get me chucked out of Angola. Blackguard, you called me. I took it. I've taken it before. I don't amount to much. I funked my last chance, in the war.

“You tackled that overseer—I'd like to have seen that—you've got what you Americans call guts. I haven't. But guts won't help you with Gomez, only to stick it out.

“Easier you take it, the easier you'll get by. Maybe, you'll get your chance. If you do, if I can help you, I will. Not now. Gomez is too up wind. I'm stayin' here to-night and I'll talk it over with him.

“To-morrow don't give him any lip and don't try to use your fists. He'll set the dogs on you, and what's left of you he'll think up things to do to. He's talented along that line. Got to go now. Here're some more cheroots. Better hide 'em if you can. So long.”

He was gone and the door locked. Dusk was coming. Waring had not been fed since morning, but he had been saving some scraps for emergency, for a chance to get away. There was no light. The mutter of drums came from the jungle. He sat by the window, listening, throwing aside thoughts of to-morrow. He had to get away. Had to!

Seole was gone. A picture of ant heaps with a writhing man tied near by, to become a skeleton after frightful torment, came to him, and he dismissed it.

“You've got to get away, got to. Got to!”

The drumbeats had got into him. Unconsciously he set the words to their rhythm, clenching the bars, hauling on them.

There was a soft crush of wood. An iron loosened slightly.

CHAPTER VI.

Weird Worship.

Africa was working for him. Stone was scarce, the bars had been set deep, socketed in hard wood that had looked solid. But the termites, the great white ants, had been at work. The sill was like a honeycomb. Upper and lower!

Waring got the lower end of one bar loose, enough to squeeze through. He worked it free at the top. It was the only weapon available. He might manage to grind down the end to a point. Meantime, it was a club.

The opening was a close fit, and he feared to make a noise. Gomez and Hawtrey were disputing in the next room. Gomez might come in at any moment. But Waring was out, in the black night, close to the jungle where the drums still throbbed. There was death there, perhaps, but worse in remaining. Gomez would be a fiend, sure of his power, devilish of invention to revenge himself for his lost dream of a fortune.

There was a sound of chanting from the barracoon. A glow shone in front of the house where the nightly fire burned in the compound, and the cressets on the palisade. Waring kept to the shadow and plunged into the dense bush.

Great twining cables, tripped him. Heavy webs of spiders swept across his face. There were thorny vines that tore his clothes and flesh. Waring blundered into trees, fell over roots. He came to a swamp and waded, chest-deep, blundering into pits of slimy water, leeches clinging to him. There was a creek beyond and he plunged into it, swimming upstream to throw off scent. Gomez would set the dogs after him, and expert bushmen.

Waring hauled out among reeds close to a bank on which were rotten logs. One came to life, lifting on squat legs, flailing a great tail, its jaws open, coming at Waring through the reeds as he thrashed to land. A crocodile!

The creek had cooled and washed the sweat from him but it broke out again, cold. Then he saw he had risked in vain. Beyond the mud bank there was a dugout, a line reeved across the stream, a ferry. It meant a trail. Waring took to it for a time, moonlight splotching down. The narrow path, its dirt hard packed by countless caravans of slaves led beneath the spreading roots of a baobab. Panting, almost done in, Waring thought of climbing into the great mass when he heard the excited bark of a dog.

The dog was after him, hot on his trail. Gomez would put the dogs across the creek in the ferry, half a mile back. Waring would be treed, brought down, likely enough like a shot monkey striking the boughs tumbling at Gomez's feet.

Desperate, out of breath, he grasped his bar and set his back against one of the root pillars. The high-riding moon lit up the path. The dogs would be ahead. Gomez was none too fast. The blacks! It was the only thing to do.

If he got away from the dogs he could strike the bush again. There was little time to plan. He saw the first of the slavering brutes racing along the trail.

Now Waring could hear Gomez, far off, shouting at his men, his voice enraged. They would not be keen for night work afraid of juju. He had a little leeway.

The brute came on direct, leaping for his throat. Waring met the charge with his knee, sending the dog sprawling. Before it could regain its feet, Waring crushed in its skull with his iron bar, bent it with the blow against the bone.

The second dog was on him. He had to drop the bar and seize it by its throat. Even then the jaws clashed within an inch of his face, its hot breath on Waring. But he swung the dog off the ground and held on, sinking his fingers into its neck, finding the windpipe, compressing it with desperate strength.

Gomez had got his men going again. Waring could see the flare of their torches.

The dog writhed convulsively, but it was choking. Its struggles lessened and its eyes glazed.

Waring cast it from him, a limp, twitching bundle, as a rifle roared. He felt the wind of the shot, the bullet striking the root bough back of him. He whirled and fled, through tangle and briars, almost exhausted, seeing by a moon ray, a bough stretched horizontally out, at which he sprang.

With his last strength he swung up, his knees over it, clambering up like a spent ape, crawling to the main trunk, hiding in the hollow of the crotch, while the torches came bobbing along, praying that the shaking leaves would not give him away.

Waring saw Gomez in his white clothes, his face like that of a furious devil. Behind him came the blacks, scared of the jungle night, Hawtrey back of them, carrying a shotgun under his arm.

Waring did not believe that he would shoot. There were remnants of decency, driblets of sporting blood in Hawtrey. But Gomez would kill. Waring crouched low. The scattered moonbeams did not reveal him. His tracks must be plain to the native trackers, where he had leaped.

Tom-tom-tom-tom. Boom!

The drums! The drums of Africa. They struck terror into the Bantus who read their rhythm aright. Their arms hung down, their eyes rolled, showing the whites, their knees shook and they bolted, back along the trail, with Gomez cursing at them. Hawtrey shook with silent laughter.

Gomez stamped his foot and Hawtrey spoke to him in Portuguese. The trader shook a baffled fist at the jungle and turned back, his dogs slain, his trackers terrified. Hawtrey followed him down the trail and Waring, peering from his nest, saw his broad shoulders shaking.

To Hawtrey it had been a sporting event. For once, the Englishman's wishes were with the quarry. Waring did not believe he would have given him away if he suspected where he was—and Hawtrey had given a sharp glance at the tree, the still slightly-moving bough.

Hawtrey would go his own way, to the devil, but chained though he was by his faults—by Gomez—he had some good left in him.

When he got back his wind, Waring went onward. The trees, fighting toward the sun, had their boughs interlocked, woven with giant lianas. He meant to keep above ground as long as he could. He had lost his weapon, but it had served him well. He dared not go back for it.

He could not entirely choose his way, and he found himself working closer to the drums. Their vibration throbbed through the forest and stilled all other night noises, sent prowling beasts from their beats, afraid of the man thunder. There was a clearing ahead. Fire leaping!

Excitement gripped Waring—Africa stirred his blood. He forgot his claw wounds and crawled out on the limb of a baobab, inch by inch. There was a strange sight beneath and beyond him.

A building, a shrine or temple, formed of great tusks set into the ground, which supported a conical roof of thatch. Inside was a hideous idol, painted bright red with black eyes and hair, outside of which black men pranced. Around the image crooked sticks were thrust into the soil, each one topped by a skull.

Waring could not see the drummers, booming away somewhere in a grove of trees, but he marked the jumping men, striped and smeared with paint. They were in a circle, roaring, lifting alternate legs and stamping three times.

A weird figure danced inside the circle, plumed with white ostrich feathers, jingling with metal anklets and armlets, clicking with bones, spotted with paint, shaking a rattle in one hand and waving the stuffed head of some animal in the other. The men had spears which they thrust upward in unison, shouting with each thrust. It was barbaric, hypnotic, but it was lacking in imagination.

A reed pipe shrieked out a shrill series of notes, and the natives leaped higher. The witch doctor danced like a Russian Cossack, kneeling, flinging out his legs to front and rear, to either side. He turned somersaults in the air, sprang upright, and yelled in a frenzy. The drums boomed on, and the pipe split the air beneath the moon.

The dance ended with astounding abruptness. A shooting star rushed down the sky, flaming atoms in its wake. The witch doctor gave a cry that topped the howls. The drums and pipe, the music and shouting ceased instantly. The fires were stamped out.

They were gone, banished by evil portent, only a few smoldering sparks remaining, that soon died out.

Waring, utterly tired, snuggled down in the hollow between four branches, and slept. Slumber took him, wrapped him in veils of merciful unconsciousness, sank him in oblivion.

The sky above him was like an opening flower of pink-and-orange petals. The jungle was awake. Monkeys chattered and swung through the treetops, birds whirled and wheeled and screamed. Flamingos and pelicans flapped across the airy void. High up, a vulture planed.

Waring looked out across the open glade where the frenzied blacks had danced about the juju shrine, leaving a ring of dirt where they had stamped out grass and herbage. Beyond was the dense, primeval forest, purplish blue of foliage through blue mists and, vaguely seen, cones and flat tops of the distant range, tipped by clouds.

Waring was in the upper boughs of a giant fig. About were acacias, mapanis, baobabs and fronded palms. He was stiff from claw strokes on breast and outer thighs. He had some scraps left, and ate them. In his breast pocket were the cheroots Hawtrey had given him, shredded by the claws of the dog he had strangled.

Waring's brain cleared as he ate, and recollection came back. He was clear of Gomez, clear of the trading post, but he did not know where to go. All about was virgin wilderness, inhabited by wild tribes. His bar was gone, he had no matches. He was bare handed and alone.

Yet Waring felt confident. He had fought and won. He could fight and win again. Something in him, remote and ancestral, kindled. He was a white man and he would survive, win through.

His lore to fit such a situation was scattered, vicarious, born of traveler's tales, but he had his white man's brains and courage. He would get through. There was food, if he could get it. Ripe fruits to hand—purple figs, refreshing and palatable, and luscious-looking grapes.

He ate, and climbed down. His tracks were far behind. He circled the clearing, going south. Loanda was a city, Portuguese, but there might be men there of kindlier trend than Gomez. He might make himself useful to them, hoard funds for a steamer passage.

But there was something that, fearsome as his experience had been, severely as he had been buffeted, linked Waring to this savage land. It was wildly beautiful, abundant.

He worked on, past trees overgrown with wild pepper, with the enormous leaves of the Elephant's Ear flourishing on the great boughs, colossal vines embracing the mighty boles, bowers of festoons inclosing spots dark as night, flowers flame-red, bells of brilliant orange. The plenitude and glory of it entered into him, used to canyoned streets. This was life, redundant and magnificent, overflowing.

Waring passed high ant hills, the insects issuing like armies on their mysterious missions. He saw francolin and guinea fowl and pondered how he might snare them. He thought of nets and lime, of snares, and realized how much he had to learn, how far he was removed from the time and ways of primitive man.

Little by little he realized his helplessness but did not let it sap his courage. He could not make fire, though he had read of savage ways. But his brain, inheritance of ancestors who had climbed their way up, should hold the source of these things.

Troops of monkeys followed him overhead, chattering, scolding, peering down with bright eyes. He saw frisking lizards, big enough for a meal. In an open space, where yellow grass waved in the wind, Waring saw deer leaping from his scent, tiny antelopes and big boks. With a catch in his breath, Waring glimpsed the chocolate-and-orange necks of giraffes, browsing high. Life in plenty!

Once more he was following a trail. It kept him on the alert, in case there should be natives traveling it, but it was much faster going and the hard-packed ground retained no sign of his tracks. He still considered it imperative to put all the distance he possibly could between him and the vindictive Gomez.

Waring came to a quaggy place like an enormous sponge, such as he had crossed the night before. It seemed strange that a path should be made to end at such a spot.

He saw no way out of crossing the morass. It stretched far in either direction, black muck from which saw-tooth edges rose stiff and thick. He sank to his knees in the sticky slime and, unable to see the way, tumbled neck deep into a series of pools that were like pits dug purposely, in their regularity. In some places the edges seemed to have been trampled down, but he was too busy getting through to pay much attention. He began to lose his newly-born complacency.

CHAPTER VII.

Primitive Combat.

Trails were, after all, Waring's best bet. They led somewhere. They had to be traveled with caution, especially where they wound between densely set trees where the undergrowth and vines wattled the jungle together like a wall on either side. But eventually, he might find a village where the natives were not altogether unfriendly. He might even meet a caravan that would look on his plight with sympathy.

But if the trails were going to be barred by swamps like these, he was not going to go either far or fast. Waring was beginning to get hungry again. Sweat broke out all over him, showing in big, salty patches on his clothes, getting into his eyes. Clouds of insects buzzed all about him, stinging and biting. Mosquitoes were so thick in the middle of the swamp that they practically blinded him, Already he could feel fever mounting in his veins.

Waring got through at last and crawled out to find the broad-and-beaten trail again, thankful for it. He broke off a green branch as some protection against the mosquitoes that had followed him from the quagmire. He walked in a green twilight, the atmosphere like that of an overworked steam laundry.

It suddenly struck Waring that the path had been made by elephants, not by man. That would account for the crossing of the swamp. The holes into which he had fallen, had been made by the herd.

Waring was thirsty, aside from his hunger. He saw fruit on vines and in the trees, some as large as his head, but it meant a stiff climb he did not feel quite up to.

Waring could assemble a motor yet he could not kill enough meat to keep him alive. He saw a pool but dared not drink. There were some growths of fruit on a dwarf tree beside the elephant trail, like small scarlet pears, or loquats. He tested them, found them slightly acid and refreshing, easing both his thirst and hunger at the same time.

Then the path ended, opening to a parklike space with trees here and there, grass growing in bunches, and bushes. And Waring saw his first wild elephants.

The wind was blowing faintly toward him and the elephants did not sense his presence. They were browsing on the leaves, pulling up the grass, rapping it against their feet to get rid of the soil, leisurely munching, while their enormous ears flapped slowly but continuously.

Tick birds rode on their backs, but gave no alarm as Waring hid back of a tree. Waring knew these mammoth creatures, pacific now, could charge with wild fury, faster than he could run or dodge, but they fascinated him.

They seemed twice his height, with humped backs and gleaming tusks. They looked like enormous pigs and gave off curious sounds, squeaks of pleasure, not the trumpetings he had expected. He saw one bull send its trunk curving down into the mouth and throat, deeply, withdrawing it to squirt water from its stomach supply over its back. Others satisfied themselves with dust. They moved silently. Now and then one passed its trunk caressingly over another.

There was no alarm. The elephants did not see Waring as he slipped from tree to tree for a closer view, and saw a gleaming lake between a broken screen of giant bamboos.

A great bull wandered toward the shore, through an opening in the grove. Out of the bamboos came a creature that belonged to past ages—eighteen feet long on legs ridiculously short, armored, hairless save for a tuft on its tail and the bristles on its big, upstanding ears.

It was the fighting keitloa, the square-nosed, white rhinoceros, two horns set into the tough hide between eyes and muzzle, the foremost curving, sharp, a formidable weapon. It had little more clearance than an armored tank as it stood there, disputing the way, ready to charge, enraged at the bull, who curled up his trunk, then extended it and stood still, too proud to retreat.

The rhino made up its mind speedily. The short, ungainly legs got into action. It raced with incredible speed, swerving slightly, lowering its head and massive tusks, coming in full tilt. The elephant wheeled, trumpeting loudly. The herd turned to see the combat.

The elephant was too slow. The rhinoceros hit the elephant well back. Both horns went in. The massive mammoth groaned, leaning to the impact of the terrific shock. The rhino heaved, striving to withdraw its horns, but could not.

The elephant, struggling to get free, trumpeted again and again. The herd began to move toward the combatants, slowly at first, then shuffling fast at neither a trot, run, nor gallop, the bulls ahead.

The rhino strove desperately to get free. The great bull began to keel over, mortally hurt. Waring gazed with awe as the enormous brute toppled and fell, pinning down its adversary, crushing the rhino with its mighty weight.

The elephant's great bulk heaved as the rhino struggled and was still. The bull elephant lay panting, its trunk whipping to and fro, stirring the dust. One great ear lifted slowly, fell with a nerveless flop. The bulls of the herd came and stood over their leader, passing their trunks over him, grunting.

A cow squealed, and suddenly the band broke into flight, making for the lake, plunging in, swimming, with only the tops of their heads showing. Best swimmers of all brutes. They crossed the water, and plunged into the forest on the opposite side.

Waring went on, aimlessly enough, across the parklike place. The fruit he had eaten was beginning to give him cramps. He chewed the shreds of Hawtrey's black cheroots to try and relieve the pain. He was hardly able to get along. At last, he flung himself down among some ferns.

Fever mounted. Waring saw great azure butterflies flitting from bloom to bloom of orchids that were beautiful. He saw monkeys staring down at him like wise old gnomes. Parrots flitted between the boughs, a ray of sun lit up a bird that gleamed with metallic plumage.

Waring felt himself lost, abandoned, a modern man thrust into a setting of thousands of years ago. Big beetles nipped at him, ants found him.

The spasms passed. Waring got up, half delirious, seeing phantoms in the aisles of the forest, jibbering figures that threatened. But he did not care. It was afternoon, as he judged it. He passed a colony of ant hills, and came to a rocky terraced ridge, which thrust itself abruptly through the jungle. Caves showed dark mouths on the ledges.

Waring essayed to reach one of them. A flock of baboons, barking, fanged like dogs, swarmed out on all fours. Highly excited, they danced up and down, pig-faced, maned like lions. Waring hurled a rock fragment at one. Instantly, a shower of stones came hurtling at him, and he had to run for cover while the baboons made bedlam that sounded like laughter.

Night came swiftly. Waring picked his tree, too far gone to try much of a climb. He dragged himself up to where he could huddle in a nook. Three close-set boughs and festooned vines hid him.

There were no drums but he heard the night sounds of the jungle—coughs, grunts, squeals as some weaker creature was caught and killed. There were mysterious rustlings, howls, the hideous, jeering laughter of hyenas. He peered through his vines and saw eyes, lambent, searching. To-morrow, he told himself, he would be stronger and go on. To-morrow he would wrest sustenance from the wilderness, demand and obtain the means of strength, carry through.

But to-night—dizzy from fever, his body smarting and swollen, stiff and sore—to-night, he was done up utterly.

CHAPTER VIII.

Magic.

Unkosi! Unkosi! Unkosi!”

Waring woke but fancied himself dreaming. That was the voice of Jim, of Seole, but Seole had been sent away by Gomez.

“Unkosi! John Waringi!”

Waring parted the vines and looked down into the face of Seole, the chief's son, smiling up at him. Seole wore his kaross and there was a knife in his belt, a spear in his hand. It was Seole, in the flesh, lifting an arm in salute to his blood brother.

Waring had never been so glad to see any one in his life. He swung down the tree with new strength, cutting a pitiful figure enough with his tattered clothes, his bites, his out-thrusting whiskers.

Seole boomed a salute. “I found the two dogs, unkosi!” he said. “They were still warm. Gomez kicked them as I watched, for I was close behind. Hawtrey was laughing. I think he was glad you got away.”

“That was my notion,” answered Waring. “How did you get here?”

“You are not hurt? The dogs did not bite you?”

“Only a few scratches.”

“Then come first, and eat.”

It seemed to Waring as if the bells of a dozen boarding houses were suddenly chiming joyfully for meals. His mouth watered. Seole had killed four small partridges with a knobkerrie he had fashioned with his knife, using the club as a missile.

He had skinned them, drawn and halved them, wrapping them in leaves and burying them from the ants. He broiled them over a fire he kindled with two sticks. The meat was tender, revivifying. There were custard apples and small bananas in the larder the Kaffir had collected with ease.

“I knew I was near you, unkosi, by the way you walked, so I left the food here, to hurry, lest you might be gone.”

They squatted by the little fire, gnawing the bones, Seole breaking them with his teeth to get at the marrow. Then he told his tale.

Gomez had put him in the barracoon, intending to sell Seole with the rest of the slaves when the next shipment was arranged. Gossip filtered in even to that dismal place. The guards purveyed it as taunts.

The half-caste overseer made it his special business to jeer at Seole. He was not permitted to whip him.

He jubilantly brought the news that Waring had pretended to be some one else, deceiving Gomez, who was going to have him bound to an ant hill.

“As for you, you Kaffir dog,” the overseer said to Seole gloatingly, “to-morrow I am to give you forty lashes. If you live—but I do not think you will live, after I am through, so I will not tell you what then is planned for you.”

“I did not believe all that he said, for the man is a liar,” Seole told Waring. “Gomez would not dare to kill a white man with ants. It would get out. Secrets travel far, even in the jungle. Hawtrey would not permit it. He is in debt to Gomez, but Gomez listens to him. If you escaped, that would be different. Gomez would try then to kill you. And I knew you would go. Even as I knew that I would.

“It was not easy for me. They light small fires for cooking inside the fence and they sit there and sing. Any who saw me would tell the guard, to find favor. Those men were born to be slaves. I waited.

“When I heard the dogs barking and Gomez shouting I knew you had gone and my heart was glad. I knew they would never take you and, when I saw those dogs, then I knew truly of what breed and what kind of a man you were.

“It was not in my mind to go without arms. You would need them as well as I, in the jungle. I climbed the posts when the shouting started, when all were excited, inside and out. He who was to flog me stood by the gate, but his men had run to where Gomez had called them. They had gone with him.

“I dropped on his back and I killed him as the lion kills. I bent back his head until his spine snapped and the life went out of him. He died easily. Then I took his knife and the spear that stood against the gate and kept in the shadows.

“I was behind Gomez all the way. It was in my mind to kill him, if he had hurt thee, unkosi. I would not have given him an easy death.

“It was not easy to trace you on the elephant path, but I found where you had plucked the red nadas. They are not good to eat, Waringi.”

Waring grinned ruefully. “I found that out,” he said. “Also, that it is not a good idea to chuck rocks at baboons. If you hadn't come along, Seole, I wouldn't have lasted much longer.”

“You would have learned. I would not wish to be in the jungle without weapons.”

“What's our best move?” asked Waring. “I thought of going to Loanda.”

Seole shook his head. “It is not a good place for strangers,' he said. “Unkosi, I was brought here in a slave train. I meant to come back, some day, so I watched. We are not far from the trail they took. We will find it.

“Toward the sun is the Kwango River. Beyond that lies Kassandu. There is a chief named Manenka and a juju man named Nsamamonze. These I know, though they may not remember me. It was there that Tilimani was taken ill. It is on a trade road.

“Manenka trades with Gomez, but he is not friendly with him. Some Kassandu men were caught out hunting and taken by the slave train. They were sold to Gomez and he sold them again.

“This I know, for I was there. Word of it passed to Manenka. Gomez denied it but Nsamamonze cast the bones and showed that he lied. Yet Manenka could not prove it, for the slavers backed Gomez.

“It was a thing done for greed and not a wise or friendly thing to do. It would have been better for Gomez to return the men and win Manenka's friendship.

“Yet Manenka trades with him, because Gomez has goods that he wants. If we can make friends with Manenka—and Nsamamonze, which is harder—he will let us stay there until some trader comes, or a hunter. It may even be that Tilimani will come, unless he has already come and gone.

“It may be that word will pass to Gomez that we are there. It may be that word will pass to Kassandu that we have fled from Gomez, and Nsamamonze will counsel handing us over for many goods, beads and cloth, wire and powder and tobacco. That is as may be, and as we fashion it.

“We shall come to Kassandu, not as most white men come, with bearers and guns. Nsamamonze fears the white man, and he hates them. You, unkosi, will make magic against him and it will be better than guns.”

“I'm not much on magic, Seole. I can do this.” Waring palmed a pebble, made a pass and showed an empty hand where the stone had seemed to go.

Seole nodded wisely. “It is a good trick. Much magic is all tricks. You will match Nsamamonze and see how he makes his magic. Then show him stronger.” Again Seole nodded, confidently. “It must be so,” the Kaffir went on earnestly, “since we bring no gifts.”

It was a long journey but, with a companion trained to the wilderness, it was not so bad. Waring learned many things about jungle ways. Seole taught him how to use a spear, made one for him out of hard wood, with the end charred in fire, and made a club of a smooth oval stone.

It was Waring who got them across the river. He fashioned a craft from two logs with a sufficient platform lashed between them. Seole made the paddles. So they made progress. Waring grew expert with the knobkerrie, made a sling of bark string and scored hits off francolin and guinea fowl.

Seole stalked a small deer on a grassy plain and killed it with the overseer's spear. He showed Waring how to catch monkeys.