Troja/Chapter 4

CHAPTER IV.

The Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Settlements on the Site of Troy.

§ I.—The Third Prehistoric Settlement.

After the great catastrophe of the second city, the Acropolis formed an immense heap of ruins, from which there stood forth only the great brick wall and the thick walls of the temples. It is impossible to say, even approximately, how long the Acropolis lay deserted; but, judging from the very insignificant stratum of black earth, which we find between the débris of the second settlement and the house floors of the third, we presume, with great probability, that the place was soon rebuilt. The number of the third settlers was but small, and they consequently settled on the old Pergamos. They did not rebuild the lower city, and probably used its site as fields and pasture-ground for their herds. Such of the building materials of the lower city, as could be used, were no doubt employed by the new settlers for the construction of their houses. On the old Acropolis the ruins and débris were left lying just as the new-comers found them; they did not go to the trouble of making a level platform. Some of them erected their houses on the hillock formed by the ruins and débris of the temples, whilst others built on the space before these edifices, on which there lay only a very insignificant stratum of débris. The house-walls of this third settlement consist, in general, of small unwrought stones joined with clay, but brick walls also occur now and then. They are covered on both sides with a clay coating, which has been pargetted with a thin layer of clay to give it a smoother appearance. The thickness of the walls varies generally between 0.45 m. and 0.65 m. The foundations of these house-walls are only 0.50 m. deep, and have simply been sunk into the débris of the second city, without having any solid foundation. For this reason the houses, with but few exceptions, cannot have been more than one story high; they have no particular characteristic ground plan, but consist of several small chambers irregularly grouped, the walls of which are often not even parallel. The largest and most regular house is the habitation repeatedly mentioned, to the north-west of the south-western gate (see p. 325, No. 188 in Ilios), which I used to consider as the royal house of the burnt city. But as we have now recognized as the Ilios of the Homeric legend the second city, which had a lower town, and which perished in a tremendous catastrophe, this largest house of the third settlement can have nothing whatever to do with that original Troy. I found the substructions of this house, as well as those of the buildings to the north of it, buried about three mètres deep in bricks, which were baked, much like those of the temple A. Hence I conclude that this house, as well as the adjacent buildings, must have had at least one high story of bricks above their substructions of small stones; and that, in the same manner as the walls of the temples and the fortification walls of the second city, these house-walls must have been baked in situ after they had been erected, by large quantities of wood being piled up on both sides of each wall and kindled simultaneously. The condition of the bricks can leave no doubt on this point, for all of them had evidently been exposed to a great fire, and besides they were very fragile; had they been baked separately, they would have been much more solid. Among the houses of the third settlement on the east side of the great northern trench X–Z (Plan VII.), there also occurred walls consisting partly of unbaked and partly of baked bricks, which latter appear to have been extracted from the heaps of ruins of the second city. Remains of such a mode of building were found, for instance, on the space before the temple A of the second city, and we are inclined to recognize in them the scanty remains of the temple of the third settlement. We infer this, first, from the considerable thickness of these walls, and secondly from the fact that the edifice stands on about the same place as that where the second settlers had their sanctuaries, for we know with what a wonderful tenacity people clung in antiquity to sacred sites.

As above mentioned, the third settlers found still, particularly on the west, south, and east sides, large remains of the Acropolis-wall of the second city, which they merely

repaired. But on the north-west side, where the citadel-hill falls off directly to the plain, and has thus a higher slope, the ancient wall had been almost totally destroyed, and here, therefore, a new fortification-wall had to be erected, which is of far inferior masonry to that of the wall of the second city, and has been indicated on Plan VII. by the letters x m and with blue colour.

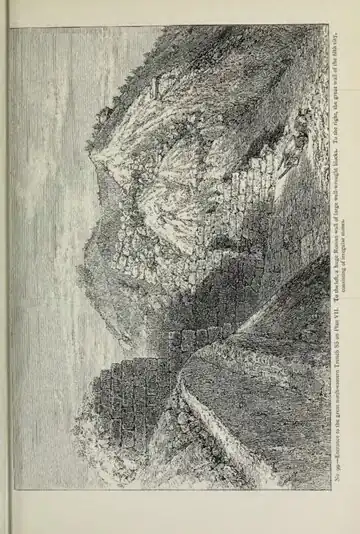

The third settlement had in the fortification-wall two-gates; the one just above the south-western, the other just above the south-eastern gate of the second city (see Plan VII.). The same positions had been maintained, probably because they gave easiest access to the Acropolis, and because the country-roads commenced and ended at these points. As may be seen from the accompanying engraving, No. 89, which represents a profile of the road leading up to the south-west gate, when the third settlers went in and out by it, the stone slabs paving the gateway of the second city were no longer visible; they were hidden beneath a layer of débris, which was about 0.50 m. deep at the gate-portals u u and x x (see Plan VII.), and about 1.50 m. outside the fortification-wall at the place TU (see Plan VII.). Even now these different heights of the pavements may be easily recognized outside the gate, in the high block of débris marked F on the Plan VII., which is still unexcavated. The gate-portals were probably arranged by the third settlers in the same way as they had been in the second city. When I excavated this gateway in the spring of 1873, I found it covered from 2 to 3 m. deep with burnt bricks, débris of bricks, and wood ashes, which prove with certainty that at the time of the third settlers also the gateway had high lateral brick walls, on which most probably some sort of an upper building was raised; but it is of course impossible to say now how much of these lateral walls had escaped the great catastrophe of the second city, and what part of them was the work of the third settlers.

In the second, the south-eastern gate (OX on Plan VII.) also, great alterations were made, but we have not been able to find out how far these belong to the second settlers, and how far to the third. The ground plan of this gate, with all the alterations, is given in the sketch No. 90. Its surface lay, at the time of the third settlement, about 1.50 mètre higher than it had been at the time of the catastrophe of the second city. Within the gate stood the sacrificial altar represented in Ilios under No. 6, p. 31. Through the gate runs a large channel or gutter of a very primitive masonry, much like the water conduit, mentioned above (p. 64) in the mysterious cavern, and the cyclopean water-conduits discovered by me at Tiryns and Mycenae.[1] It is formed of rude unwrought slabs of limestone joined without cement, and covered with similar stones. This channel cannot have served for carrying off the blood of the sacrificed animals, as I at first supposed (Ilios, p. 30); it is too deep for that; besides, it extends in a north-westerly direction into the city, and therefore probably served for carrying off the rain-water.

Like the south-western gate, this south-eastern gate also must have had on the substructions (b, b in the engraving No. 90 and w in Plan VII.) long and high lateral walls of bricks, and must have been crowned with a tower of the same material, for otherwise we should be at a loss to account for the masses of fallen baked or burnt bricks and débris of bricks, 3 mètres deep, in which we found the sacrificial altar and its surroundings imbedded. But I may say of these lateral walls the same that I said of those of the south-western gate, namely, that it is impossible to say now what part, if any, of these walls belongs to the second city. But the great difference in the level of the surface of the two gates rather induces us to believe that the old lateral walls had been at least in great part destroyed, and that most of the bricks and brick débris which encumbered the upper gateway belong to the lateral walls and upper construction built by the third settlers, and that the latter employed in both gateways the system repeatedly described as used by their predecessors, of baking the brick walls entire. The altar may already have stood in the gate when the walls were fired, for not only the outward appearance of the square plate of slate granite with which it was covered, and the great block of the same stone cut out in the form of a crescent which stood above it, but also the fractures of these slabs, all denote that they have been exposed to a great incandescence.

Professor Sayce observes to me that "brick walls, similarly baked after their construction, have been found elsewhere. For example, the sixth stage of the great temple of 'the Seven Lights of Heaven,' built by Nebuchadnezzar at Borsippa, and now known as the Birs-i-Nimrùd, was composed of bricks vitrified by intense heat into a mass of blue slag after the stage was erected. In Scotland, also, vitrified forts have been discovered, of which the best known is Craig Phadric, near Inverness, where the walls have been fused into a compact mass after they have been built. Here, however, the walls are made of stone and not of brick."

Mr. James D. Butler, President of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, writes me on this interesting subject as follows:—

"Madison, Feb. 14, 1883.

"Henry Schliemann, Esq.

"In the London Times of January 26, I am pleased with your Trojan letter, especially with your discovery of an inversion of our mode of making brick.

"It seems odd to lay them up crude and then bake them. But I came to the same conclusion regarding a ruin near here which I explored last summer.

"The place, 50 miles east of here, on the way to Milwaukee, is called Aztulan. At that point about 18 acres were inclosed by a breast-work forming three sides of a parallelogram, the fourth side lying along a stream too deep to ford. There were 33 projections, considered flanking towers. The wall, when discovered in 1836, was about 4 feet high. It seems to have been once higher. The ground was first heaped up—and then coated with clay; the clods matted and massed together with the coarse prairie grass and bushes. Over all similar grass and bushes were piled and set on fire. The clay, of course, became brick, or an incrustation of brick. The soil still abounds in brick fragments, though the ploughshare has already for forty years been destroying this grand unique relic of some prehistoric race.

"This 'ancient city,' as it is locally styled, was first described in the Milwaukee Advertiser in 1837, in the American Journal of Science, New Haven, 1842, vol. xliv. p. 21, and more fully in 1855 by Lapham, in the Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, vol. vii. pp. 41–51.

"No explorer before myself, last May, appears to have felt that the brick or terra-cotta crust was baked in situ, as you describe the walls of Troy. An article of mine was published in the State Journal of this city, May, 22, 1882. I stated that one fragment I brought away had a stick an inch thick in the middle of it burned to charcoal, and that every bit of the terra-cotta showed holes where the sedge from the river bank had been mixed with the clay to help in burning it to brick."

The destruction of the third settlement was not total, for its city-wall and its house-walls have remained standing to a considerable height down to the present time.

Though we see traces of fire in several houses of the third settlement, yet nothing here testifies to a catastrophe such as took place in the second city, where all the edifices were destroyed to the very foundations, and only the thick walls of the temples, the citadel-wall, and perhaps the lateral walls of the gateways, have partly escaped destruction.

As explained in the preceding pages, my collaborators at Troy in 1879 agreed with me in attributing erroneously to the second city only the strata of débris, from 3 to 4 mètres thick, which succeed to the layer of ruins of the first city, and which we now find to have been artificially heaped up by the inhabitants of the second city to make a great "planum" for their Pergamos. Consequently the objects of human industry found in this layer and represented in Ilios, pp. 271–304, Nos. 147–181, as belonging to the second city, certainly belong to it. About this there is no mistake; but we have now ascertained with certainty that they belong to the oldest epoch in the history of the second city, and that to the second city belong also the thousands of objects which I found in the calcined ruins, and which I had formerly attributed erroneously to the third settlement. Now as some places in the house-floors of the third settlers are only separated by a layer of débris 0.20 m. thick from those of the burnt city, the objects of human industry which belong to them have naturally become mixed up with those of the second city. As we have had in this last Trojan campaign thousands of opportunities to convince ourselves by gradually excavating layer by layer from above, the third settlers could only have been very poor, for we found but very little in their houses. There can consequently be no doubt that nearly all the objects discussed and represented in Ilios in the chapter on the third city, pp. 330 to 514, Nos. 190–983, really belong to the second, the burnt city. It might even be very easy now to make the separation, for all the objects found in the burnt city bear the most evident marks of the intense heat to which they have been exposed in the great catastrophe, and all the pottery has become thoroughly baked by it, whilst, like all other Trojan pottery, the pottery of the third settlement proper is but very superficially baked. But it would lead us too far to undertake the separation now; we prefer to leave it for a new edition of Ilios, and here merely to put the facts on record.

I give under Nos. 91–96 a few objects which I picked up in the houses of the third settlement, and which differ slightly from those represented before. No. 91 is a one-handled hand-made jug with two separate spouts, one behind the other, though there is no separation in the body of the vessel. The front is ornamented with three breast-like excrescences. No. 92 is a vase with a hollow foot and a long perpendicularly perforated excrescence on each side of the body, and corresponding holes in the rim. No. 93 is a cup with a handle, a flat bottom, and an ear-like

ornament in relief on each side of the body. All this pottery is but very slightly baked. More thoroughly baked is the clay ring No. 94, probably because it was to be used as a stand for vases with a convex bottom.

Nos. 95, 96 are two astragals (huckle-bones). I represent them here instead of the two astragals Nos. 530, 531, p. 426, in Ilios, which were badly photographed. To avoid repetitions I represent here no more pottery. The whorls, both ornamented and unornamented, occurred by hundreds. Of brooches of bronze with a globular or a spiral head perhaps a dozen were gathered; also many awls and needles of bone, like those shown in Ilios, p. 261, Nos. 123–140, and p. 430, Nos. 560–574; hundreds of saddle-querns of trachyte,

Size 1:2; depth about 8 m.

like those at p. 234, No. 75, and p. 447, No. 678; rude stone hammers, like those at p. 237, No. 83, and p. 441, Nos. 632–634; corn-bruisers, like those at p. 236, Nos. 80, 81; saws and knives of flint or chalcedony, like those at p. 246, Nos. 93–98, p. 445, Nos. 656–664, etc.

§ II.—The Fourth Prehistoric Settlement on the Site of Troy.

As above mentioned, my architects ascertained beyond all doubt that the third settlement never perished in a catastrophe, for the remains of its house-walls still stood from 2 to 3 mètres high, and its walls of fortification were more or less well preserved. The fourth settlers built their houses on the gradually accumulated ground of the hill, and on the ruined house-walls of their predecessors. My architects further found that the fourth settlers used the brick walls of the third settlement, after having repaired them, and perhaps having built them somewhat higher, in proportion to the increased height of the ground. The fourth settlement, therefore, did not extend any further than the third, and consequently, like the latter, it only occupied the Pergamos of the second city. It had its gates, which were probably of wood, exactly at the same places as the third settlers had had theirs, but, as visitors may observe in the still standing vertical block of débris, F on Plan VII., the surface within the gates had again become 1.50 m. higher. The whole ground within the fortification-walls was covered with the houses of the fourth city, their ground-plans having no regular form, but consisting, like the houses of the third settlement, of small chambers irregularly grouped together. The house-walls were built of a masonry of small quarry-stones joined with clay; but their dimensions were in general still smaller than those of the house-walls of the third city; we even see some house-walls only 0.30 m. thick. Besides, some of the house-walls were built of bricks, partly baked, partly unbaked. I call the attention of visitors to a wall of unbaked bricks, which may still be seen in the great block of débris, marked G on Plan VII., which has remained standing to the south of the temple A. The bricks are made of clay mixed with straw, and are 0.45 m. square and 0.07 m. high; they are joined with a cement of a whitish clay. The thickness of the walls, only one brick in breadth, measures, inclusive of the coating on both sides, 0.47 m. Considering the thinness of most of the house-walls of this fourth settlement, it is not probable that there could have been an upper story above the ground floors, which are still partially preserved: in fact, as in the third settlement so also in the fourth, most houses appear to have had only a ground floor. Both these settlements, as brought to light by the excavations, certainly give the impression of mere villages. No tiles were found in the fourth settlement, for, as in the preceding cities, all the houses were roofed with horizontal terraces, which, as we still see in the villages of the Troad, were made of wooden beams, reeds, and a layer of clay about 0.25 m. thick. It is especially the existence of these horizontal terraces, the clay of which is constantly being washed away by the rain and must always be renewed, that explains that rapid accumulation of the ground, which we find in the prehistoric settlements on the hill of Hissarlik, and which has never yet been observed elsewhere in anything like such proportions. This also explains the tremendous masses of mussel and other small shells, some of which are still closed. The house-walls of clay-bricks must also have contributed to the rapid accumulation of débris, for by the alternate influence of rain, sunshine, and wind, these bricks get completely dissolved.

We cannot say with certainty how the fourth settlement came to an end; but, as we found the upper part of its fortification-walls destroyed, it is natural to suppose that the settlement may have perished by the hand of enemies. We see in several houses traces of fire, but these are not more considerable than those in the third settlement, and certainly there has not been a general destruction.

We found again in the débris of the fourth settlement a very large quantity of pottery, like that represented and discussed in Ilios, pp. 521–562, Nos. 986–1219, but no new types, except two vases with owl-faces and the characteristics of a woman, which I represent here under Nos. 97, 98, because they differ from any of those I have shown in Ilios.

On the vase No. 97, the owl-face is very rude; the beak is long and pointed, the eyes are indicated by semi-globular dots; the eyebrows by a horizontal line in relief; the female breasts and vulva are well marked; the rim of the orifice

is bent over; the bottom is flat; the wings are indicated by vertical projections. No. 98 is one of those vases which have two wing-like vertical projections, two female breasts and the vulva, but a smooth cylindrical neck, on which is put a separate cover with an owl-face. This vase-cover is particularly remarkable for its large semi-globular eyes and high protruding eyebrows.

The forms of these sacred Trojan vases have changed somewhat in the course of ages; but, although they have lost their owl-heads and wings, yet their types may easily be recognized in the vases with two female breasts with which the potters' shops in the Dardanelles abound.

There also occurred in this stratum hundreds of ornamented and unornamented terra-cotta whorls, and many brooches of bronze, some knives of the same metal, many needles and awls of bone, innumerable rude stone hammers as well as saddle-querns, and a large number of well-polished axes of diorite, like those represented in Ilios under Nos. 1279–1281, p. 569.

§ III.—The Fifth Prehistoric Settlement on the Site of Troy.

(Upload an image to replace this placeholder.)

The fifth settlers cannot have used the old fortification walls, for the accumulation of débris had been so great that those walls were completely buried. Although my architects have not succeeded in finding a fortification-wall which could with certainty be attributed to the fifth settlement, yet we have brought to light in two places a citadel-wall of large rudely-wrought calcareous blocks, which we can, at least with the highest probability, indicate as the wall of the fifth city. This wall is now visible, first, in the great north-west trench (n z on Plan VII. in this work and Z'–O on Plan I. in Ilios); and, again, at the northeastern end of the great north-eastern trench (SS on Plan VII.). We struck it immediately below the Roman and Greek foundations, at a depth of about 2 m. below the surface of the ground, and excavated it to a depth of 6 m. As before mentioned, it is distinguished by its masonry from the fortification-walls of the more ancient prehistoric cities, for it consists of long plate-like slabs, joined in the most solid way without cement or lime, which have very large dimensions, particularly in the lower part, whilst the lowest part of the walls of the second city consists of smaller stones of rather a cubical shape. The accompanying woodcut, No. 99, gives a good view of this wall of the fifth city, as it was brought to light in the great northeastern trench (SS on Plan VII.). It deserves attention that this wall is outside and to the north-east of the Acropolis of the second city, in fact near the north-east end of the Greek and Roman Acropolis of Ilium.

The objects of human industry found were of the same kind as those described and represented on pp. 573–586 in Ilios; I have no new types to record, except two vases with owl-heads, and two small objects of ivory, which I represent here under Nos. 100–103.

The vase, No. 100, is peculiar for the long pointed owl's beak and the well-indicated closed eyelids; only two female breasts are indicated, and no vulva. The neck of the vase, which is very long and cylindrical, is ornamented with three incised circular lines, meant possibly to represent necklaces. The rim of the orifice is turned over; the bottom is flat; two long upright projections indicate the wings.

On the vase No. 101 the eyes are large and protruding; the ears are not indicated; the beak is but small and on a level with the eyes; just below it is a small round groove, in the centre of which is a minute perforation; probably this is meant to represent the mouth; the two female breasts and the vulva are very large and conspicuous; the latter is peculiarly interesting on account of the incised 卍 with which it is ornamented, and which seems to corroborate M. Emile Burnouf's[2] opinion, that the 卍 represents the two pieces of wood laid across, in the junction of which the holy fire was produced by friction, and that the mother of the holy fire is Mája, who represents the productive force in the form of a woman. This appears to us the more probable as we also see a 卍 on the vulva, of the idol No. 226, p. 337, in Ilios; and very often crosses, as for example, a cross with the marks of four nails on the vulva of the owl-faced vase No. 986, p. 521; a simple cross on that of the vase No. 991, p. 523, &c. Instead of the usual wings, we see on the vase No. 101 mere stumps, which do not appear to have been longer; three incised lines round the back seem to indicate necklaces; two other lines run across the body; there is a groove at their juncture.

No. 102 is a curious object of ivory with sixteen rude circular furrows, which seem to have been made by a flint-saw; the use of this object is a riddle to us, for it can hardly have been used in ladies' needle-work. Another curious object is No. 103, which is hollow and has three perforations and two circular incisions, apparently made by a flint-saw. The object may have served as a handle to some small bronze instrument.

§ IV.—The Sixth or Lydian Settlement on the Site of Troy.

Above the layer of ruins and débris of the fifth prehistoric settlement, and just below the ruins of the Aeolic Ilium, we found again a large quantity of the pottery described and represented in Ilios, pp. 590–597, Nos. 1363–1405, which, as explained in Ilios, p. 587, from the great resemblance this pottery has to the hand-made vases found in the ancient cemeteries of Rovio, Volterra, Bismantova, Villanova, and other places in Italy, and held to be either archaic-Etruscan or prae-Etruscan pottery, as well as in consideration of the colonization of Etruria by the Lydians, asserted by Herodotus (1. 94), I attribute to a Lydian settlement that must have existed here for a long time. There were again found the same vase-handles as before, in the form of snakes' heads, or with cow-heads (see Ilios, pp. 598, 599, Nos. 1399–1405). Regarding the latter I may mention that I found at Mycenae a large painted vase, the handles of which are modelled with cow-heads (see Mycenae, p. 133, No. 213, and p. 139, No. 214). An Etruscan vase ornamented with a cow's head is in the Museum at Corneto (Tarquinii). Dr. Chr. Hostmann, of Celle, kindly informs me that vases with handles terminating in cow-heads have been discovered at Sarka near Prague, and that they are preserved in the Museum of the latter city. A similar vase, found in an excavation at Civita Vecchia, is in the Museum of Bologna.

There were again found six of the pretty, dull-blackish, one-handled cups, with a convex bottom and three hornlike excrescences on the body, similar to those represented in Ilios, p. 592, Nos. 1370–1375. The Etruscan Museum in the Vatican contains two similar cups, the Museo Nazionale in the Collegio Romano three. These latter were found in the necropolis of Carpineto near Cupra Marittima. I may further notice the discovery of two more double-handled cups like No. 1376, p. 593, in Ilios: two similar ones, found at Corneto (Tarquinii), are preserved in the museum of that city. Also two more of those remarkable one-handled vessels, like No. 1392, p. 596 in Ilios, which are in the shape of a bugle with three feet. Similar vessels, but without feet, may be seen elsewhere: the Etruscan Collection in the Musée du Louvre contains a number of them; one may also be seen in the Etruscan Collection in the Museum of Naples; another, found in Cyprus, is in the collection of Eugène Piot at Paris.

I repeat here from Ilios, pp. 588, 589, that with rare exceptions all this pottery, which I hold to be Lydian, is hand-made, and abundantly mixed with crushed silicious stones and syenite containing much mica. The vessels are in general very bulky; and as they have been dipped in a wash of the same clay and polished before being put to the fire, besides being but very slightly baked, they have a dull black, in a few cases a dull yellow or brown colour, which much resembles the colour of the famous hut-urns found under the ancient layer of peperino near Albano.[3] This dull black colour is, however, perhaps as much due to the peculiar mode of baking as to the peculiar sort of clay of which the pottery is made, for, except the πίθοι, nearly all the innumerable terra-cotta vases found in the first, third, fourth, and fifth prehistoric settlements of Hissarlik are but very superficially baked, and yet none of them have the dull colour of these Lydian terra-cottas. Besides, the shape and fabric are totally different from those of any pottery found in the prehistoric settlements or in the upper Aeolic Greek city. The reader of Ilios and the visitor to the Schliemann Museum at Berlin, will recognize this great difference in shape and fabric in the case of every object of pottery represented in Ilios (pp. 589–599) or exhibited in that Trojan collection at Berlin.