Utah and the Mormons/Chapter 1

CHAPTER I.

FROM MISSOURI TO UTAH.

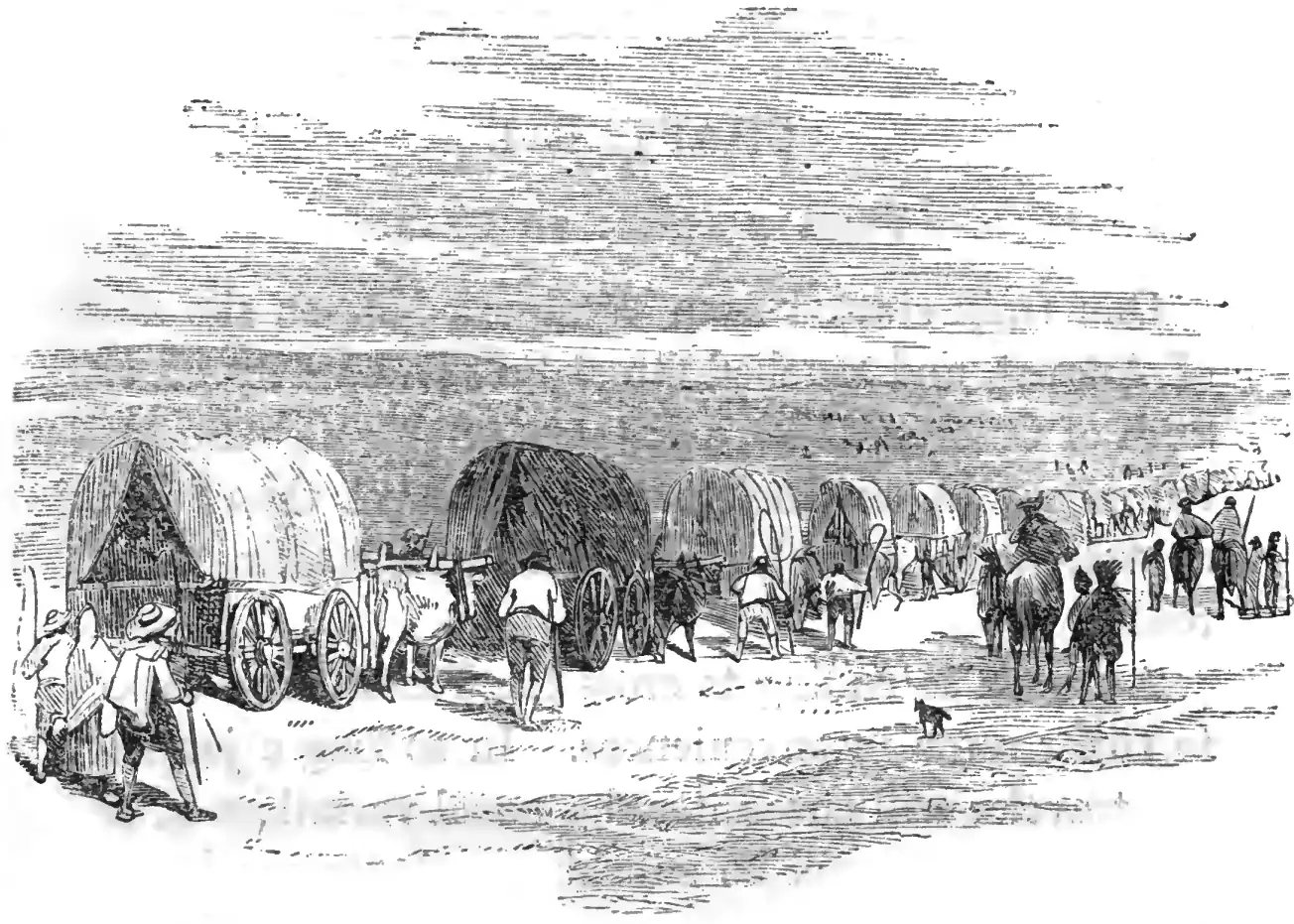

Our train started from Westport, Mo., on the 24th of August, and reached Great Salt Lake City on the 26th of October, 1852, a distance of over eleven hundred miles. A few incidents of the travel, though over so well-beaten a road, may not be uninteresting to the reader.

A person intending to cross the Plains must expect to suffer some inconveniences. In so long a journey, the traveler will encounter the usual variations of the weather: there will be sunshine and storms; he will be too hot, too cold, and too wet at times; he will sometimes be unable to quench his thirst, except from a stagnant pool; and every warm evening he must look for a fight with musquitoes, whose appetites are quite as keen as his own. At first he will feel some anxiety in regard to Indians, and keep his rifle and revolver in proper shooting condition; but this soon wears off, and before the journey is half ended he becomes altogether too careless in this respect. We had, one evening, an Indian alarm, after being four weeks upon the road, when one revolver proved to be the only fire-arm in order in the camp; the alarm, however, was occasioned by a gang of famished wolves, trying to form an acquaintance with our mules. With ordinary foresight in reference to the requisite supply of food, a proper selection of animals, and the time and mode of performing the journey, there need be but few hardships. It

CROSSING THE PLAINS.

is easy to fit up a carriage with conveniences for sleeping, which some do, but the majority prefer to sleep on the ground, even in stormy weather. An india-rubber cloth spread upon the thick grass makes a dry and soft bed; at any rate, this kind of dormitory, curtained with heaven's canopy, generally proves more friendly to sleep than many a bed of down. The fatigue of traveling wears off in a very short time, and there is usually less weariness at the close of the day than is felt in traveling the same number of hours by rail-road. In a well-regulated train, the pleasurable excitements of the journey far outbalance all the inconveniences. There is a kind of cutting loose from the business relations and customs of civilized life, which gives new freedom and elasticity to the mind. The traveler feels that he has sufficient elbow-room; he neither jostles nor is jostled by any one; he experiences all the buoyancy of the boy when liberated from the restraints of the school-room. His feelings and ideas expand in view of the boundless plains spread before and around him. There is a grandeur and sublimity in the vast expanse of plains, skirted and intersected by rivers and lofty mountains, which would kindle enthusiasm in the bosom of the merest business drudge of the countinghouse who dreams only of prices and profits.

CROSSING THE PLAINS.

is easy to fit up a carriage with conveniences for sleeping, which some do, but the majority prefer to sleep on the ground, even in stormy weather. An india-rubber cloth spread upon the thick grass makes a dry and soft bed; at any rate, this kind of dormitory, curtained with heaven's canopy, generally proves more friendly to sleep than many a bed of down. The fatigue of traveling wears off in a very short time, and there is usually less weariness at the close of the day than is felt in traveling the same number of hours by rail-road. In a well-regulated train, the pleasurable excitements of the journey far outbalance all the inconveniences. There is a kind of cutting loose from the business relations and customs of civilized life, which gives new freedom and elasticity to the mind. The traveler feels that he has sufficient elbow-room; he neither jostles nor is jostled by any one; he experiences all the buoyancy of the boy when liberated from the restraints of the school-room. His feelings and ideas expand in view of the boundless plains spread before and around him. There is a grandeur and sublimity in the vast expanse of plains, skirted and intersected by rivers and lofty mountains, which would kindle enthusiasm in the bosom of the merest business drudge of the countinghouse who dreams only of prices and profits.

The evening camp, too, has its peculiar pleasures: the rude preparation for, and exquisite relish of the evening meal—the boisterous good humor of the company, with the usual concomitants of song and anecdote—and the almost invariable, and, withal, plaintive serenade from a score or two of prairie wolves, produce a wild and pleasurable excitement, which the voyageur is ever fond of calling to remembrance.

There is an abundance of wild game along nearly the whole route: prairie chickens, ducks, hare, antelope, &c., afford rare sport in the hunting, and furnish food fit for an emperor. But the buffalo is the most noted, useful, and interesting of all the wild game to be found on the plains. We saw none until after we left Fort Kearney, after which we met vast numbers along the Valley of the Platte, and very few after leaving that river. At a distance they look like herds of common cattle; near at hand they are awkward, misshapen monsters enough—all head and shoulders, and very little of any thing else. They were very wild, and invariably ran off, as we approached, with a clumsy, lumbering gait. We saw them under a great variety of circumstances. On one occasion, a herd of them were crossing the Platte in single file (the way they usually travel), and appeared in the distance like abutments for a gigantic bridge or aqueduct about being built. At another time we approached nearer than usual to a drove of them before they perceived us, and, as they lumbered off, they produced a stampede of our whole train, and it was with much difficulty we stopped and quieted our mules. At another time a herd of some three thousand were feeding along the banks of the river, and never discovered us until we were passing nearly opposite, when the monsters, in their fright, scampered directly toward us, and actually ran between different portions of our train; two of the teams, less guarded than the rest, stampeded after them. These incidents always furnished subjects for mirth when we found no bones or wagons broken. Of course, the poor brutes are slaughtered without mercy by Indians and emigrants. We had a plentiful supply of buffalo beef during four weeks of our journey. The ravens and wolves that hover over and around every passing train, are the scavengers which clean up all that is left of the slain buffalo after man has helped himself to the choicest portions. The antelope is a very graceful animal, and bounds over the plains with the fleetness of deer, which it very much resembles. We saw many of them, but they do not collect in such herds as the buffalo.

The emigration over the Plains to Utah, California, and Oregon, for the last few years, has been immense, and, like the march of armies, each train has left sad memorials of its passage. The wayside in very many places is literally strewed with the bones of oxen and mules, the broken fragments of wagons, and the castoff implements of agriculture. Sadder still, the road is lined with graves—some small, showing that there the mother has been compelled to deposit the remains of her infant child, and others of sufficient length to show that the strength of manhood has been brought to the dust. Many of these graves had been rifled by the wolves, and the bones scattered around in confusion: these resurrectionists have no fear of penal enactments. Others were protected from these prairie surgeons by logs and rocks (every thing West, from a twenty ton boulder to a pebble, is a rock). In passing these evidences of mortality, one can form some faint conception of the utter feeling of desolation which must overwhelm the poor wife, thus compelled to deposit her husband in a lonely grave, far away from the assistance and sympathy of friends.

"The Plains," so called, commence at the western bounds of Missouri, and extend to the vicinity of the Black Hills, a distance of about seven hundred miles. These Plains consist mostly of rolling prairies, which are crossed by numerous streams. Some of these streams run through comparatively deep valleys, and have rocky and precipitous banks. Again, the Plains are intersected by numerous gulleys, or "pitch holes," as they are familiarly called, varying from ten to fifty feet, which contain small brooks in the spring and early part of summer, but the most of them become dry later in the season. These gulleys are troublesome to cross, in proportion to their depth and the steepness of their banks. On the other hand, many of them contain springs of excellent water, and a scanty growth of timber, furnishing to the traveler wood and water, without which he could not long prosecute his journey. At some points the Plains are almost a perfect level, without a tree or a shrub to relieve the eye—an ocean, in which one seems to be out of sight of land.

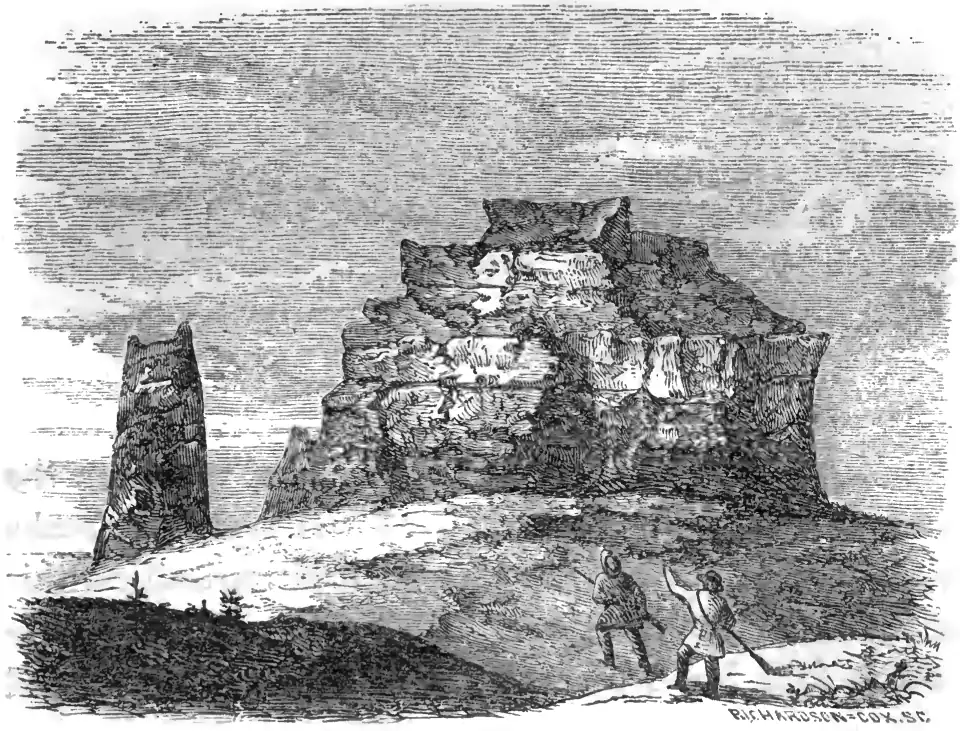

We reached the River Platte a few miles east of Fort Kearney. This fort is commanded by Captain Wharton, a gentlemanly and highly intelligent officer. We were received and entertained by him and his accomplished lady not merely with generous hospitality, but with as much warmth as though we had been near relatives. At this point, and for a considerable distance west, the Platte runs through a valley from five to eight miles, bounded by a low range of sand-hills. The country becomes more and more interesting from Fort Kearney westward. The sand-hills, as you progress up the stream, are more bold and irregular, until they run into rugged and rocky ranges, worn and washed into sharp peaks and every variety of outline. One of the most singular of these rocky elevations has been called the "Court-house," from its fancied resemblance

COURT-HOUSE ROCK.

to a public building; but it is a misnomer to give it so common a name. It is a large mass of reddish sandstone, rising abruptly from the plain in solitary grandeur, and in the distance looks like an immense temple, or castle, reared to some heathen divinity, or by some feudal baron in ages gone by, but now in a state of decay.

COURT-HOUSE ROCK.

to a public building; but it is a misnomer to give it so common a name. It is a large mass of reddish sandstone, rising abruptly from the plain in solitary grandeur, and in the distance looks like an immense temple, or castle, reared to some heathen divinity, or by some feudal baron in ages gone by, but now in a state of decay.

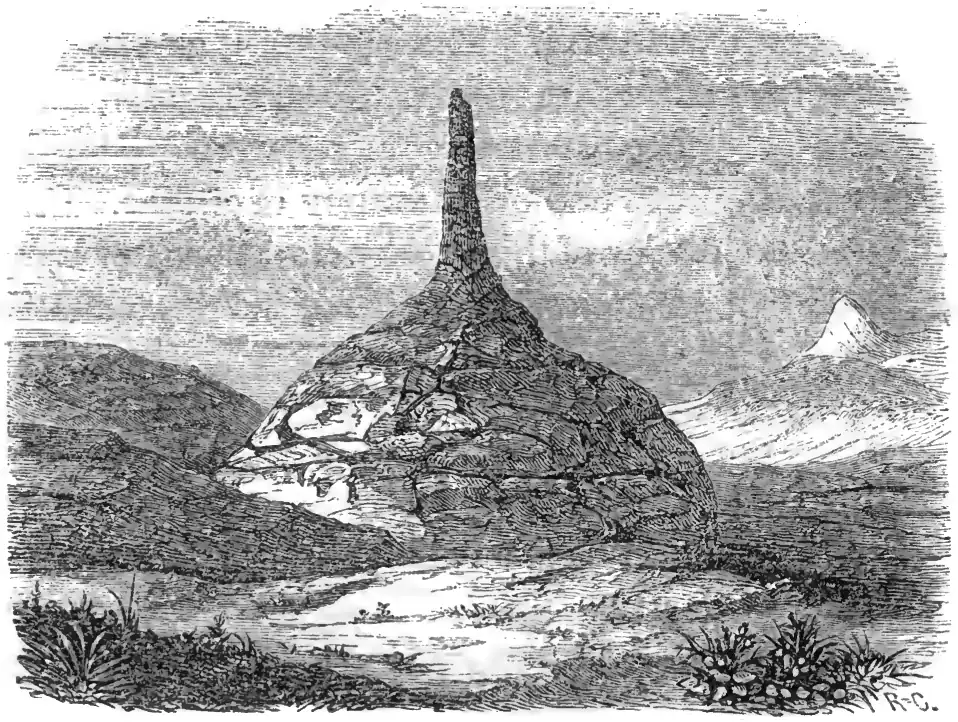

Some fifteen miles from the Court-house you see the justly celebrated Chimney Rock, pointing its solitary column to the sky, and from which you every moment

CHIMNEY ROCK.

expect to see issuing smoke or jets of steam from the fancied furnace beneath. Of all the fantastic freaks of Dame Nature in fashioning natural curiosities, this is certainly the strangest. The chimney rises some 150 to 200 feet from the apex of pyramidal-shaped rock, all reddish sandstone. But this curiosity has been well described in many published journals, and I will not, therefore, inflict another description upon the reader. After leaving Chimney Rock, we came very soon to Scott's Bluffs, which we left to the right, and

CHIMNEY ROCK.

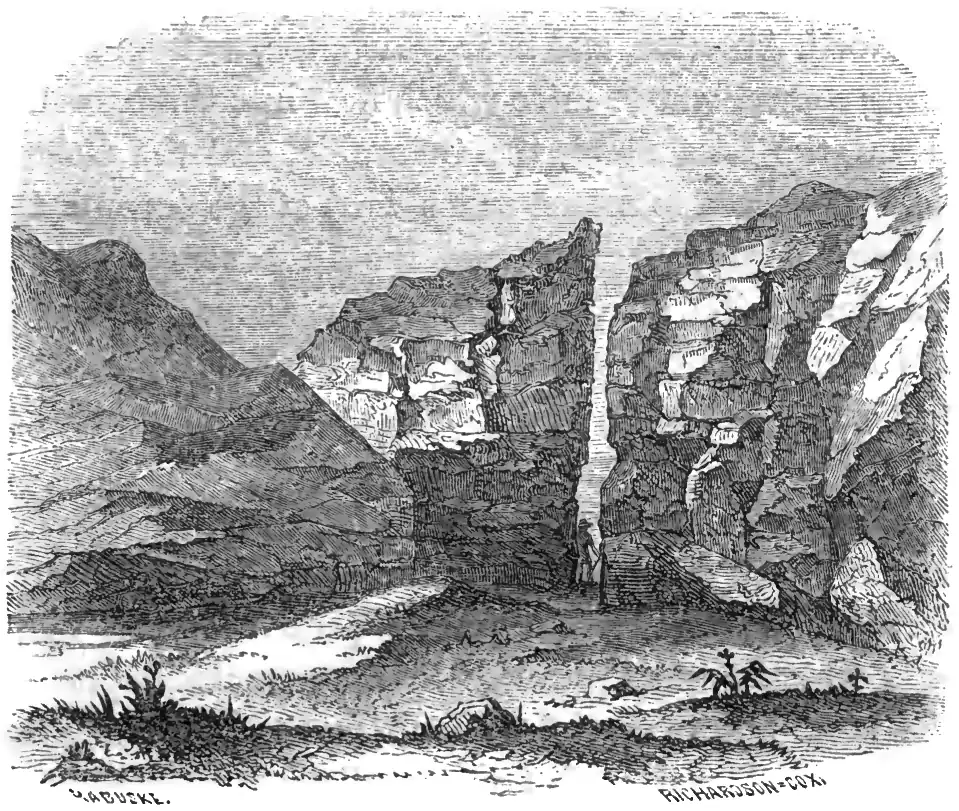

expect to see issuing smoke or jets of steam from the fancied furnace beneath. Of all the fantastic freaks of Dame Nature in fashioning natural curiosities, this is certainly the strangest. The chimney rises some 150 to 200 feet from the apex of pyramidal-shaped rock, all reddish sandstone. But this curiosity has been well described in many published journals, and I will not, therefore, inflict another description upon the reader. After leaving Chimney Rock, we came very soon to Scott's Bluffs, which we left to the right, and  SCOTT'S BLUFFS.

passed up a valley lined on each side with similar curiosities. Here was a castle with its turrets and battlements—there, an extensive fort, with parapets and bastions—and yonder, huge, misshapen, beetling crags. One formation excited especial interest. There was first a gigantic perpendicular rock in the form of a cylinder, which served as a foundation, on which arose a smaller rock of the same form, and on that a third, still smaller, but of the same form. It looked like the vast mausoleum of some hero of a past race. The lover of natural scenery feels amply paid for all the dangers, inconveniences, and petty annoyances of such a journey, while viewing these curiosities, scattered, as it were, broadcast, on a scale of such magnificent grandeur.

SCOTT'S BLUFFS.

passed up a valley lined on each side with similar curiosities. Here was a castle with its turrets and battlements—there, an extensive fort, with parapets and bastions—and yonder, huge, misshapen, beetling crags. One formation excited especial interest. There was first a gigantic perpendicular rock in the form of a cylinder, which served as a foundation, on which arose a smaller rock of the same form, and on that a third, still smaller, but of the same form. It looked like the vast mausoleum of some hero of a past race. The lover of natural scenery feels amply paid for all the dangers, inconveniences, and petty annoyances of such a journey, while viewing these curiosities, scattered, as it were, broadcast, on a scale of such magnificent grandeur.

Near Fort Laramie the highlands commence; the country is broken up into hills and irregular prominences, and the traveling becomes more laborious. We left the Platte and reached the Sweetwater, a few miles east of Independence Rock. This is an immense, irregular pile of granite, about 120 feet high, and from one and a half to two miles in circuit, full of seams and fissures. I climbed to the top, and saw

STEEPLE ROCKS.

a beautiful hare, which soon retreated into one of the numerous cavities. The rock is literally covered with the names of travelers; at a rough guess, there must be 35,000 to 40,000! This is an easy way of handing one's name down to posterity, and Thomas Noakes stands quite as good a chance in this respect as the celebrated John Doe. Let any one who is puzzled for a name visit this rock.

STEEPLE ROCKS.

a beautiful hare, which soon retreated into one of the numerous cavities. The rock is literally covered with the names of travelers; at a rough guess, there must be 35,000 to 40,000! This is an easy way of handing one's name down to posterity, and Thomas Noakes stands quite as good a chance in this respect as the celebrated John Doe. Let any one who is puzzled for a name visit this rock.

The Valley of the Sweetwater furnished us a smooth, level road until near the sources of the river. On the north side are the Rattlesnake Hills, a range of bare granite, varying from 500 to 1000 feet high, and of precisely the same character as Independence Rock. It is cracked and seamed at all points, and may well be the resort of the rattlesnake for a thousand years to come. For some days before we reached the South Pass, the Wind River Mountains, with their snowy peaks glittering in the sunshine, appeared in view. These constitute some of the loftiest portions of the Rocky Mountains. The celebrated South Pass proved to be somewhat different from my previous conceptions. The word pass induced the belief that it partook of the

DEVIL'S GATE (South Pass).

character of a gorge between lofty mountains; but it is quite different from this. The country from the vicinity of Fort Laramie to the summit is made up of ascending highlands; the road is up and down, but there is more of up than down. Some fifteen to twenty miles from the summit, the highlands become more bold and difficult of ascent, and the rocks by the way side crop out in sharp, perpendicular points. As we approach the summit, the surface becomes more even and gently rolling, and the exact dividing point is passed before one is aware of it. The wind was high and cold. Some twenty miles to the right was a ridge of high hills, and further still, in the distance, were the Wind River Mountains. On the left were irregular highlands. There is something exciting in the idea that one is passing over the topmost point of travel in all North America, and near which, too, as from a radiating centre, waters arise which flow into three mighty rivers, the Mississippi, the Columbia, and the Colorado. Some ten to fifteen miles west of the summit the descent is very obvious, and the air becomes milder. On the Pacific side, the mountains above referred to are magnificent beyond description; they seemed, in the bright sunshine, like immense masses of thunderclouds gathering for a storm.

DEVIL'S GATE (South Pass).

character of a gorge between lofty mountains; but it is quite different from this. The country from the vicinity of Fort Laramie to the summit is made up of ascending highlands; the road is up and down, but there is more of up than down. Some fifteen to twenty miles from the summit, the highlands become more bold and difficult of ascent, and the rocks by the way side crop out in sharp, perpendicular points. As we approach the summit, the surface becomes more even and gently rolling, and the exact dividing point is passed before one is aware of it. The wind was high and cold. Some twenty miles to the right was a ridge of high hills, and further still, in the distance, were the Wind River Mountains. On the left were irregular highlands. There is something exciting in the idea that one is passing over the topmost point of travel in all North America, and near which, too, as from a radiating centre, waters arise which flow into three mighty rivers, the Mississippi, the Columbia, and the Colorado. Some ten to fifteen miles west of the summit the descent is very obvious, and the air becomes milder. On the Pacific side, the mountains above referred to are magnificent beyond description; they seemed, in the bright sunshine, like immense masses of thunderclouds gathering for a storm.

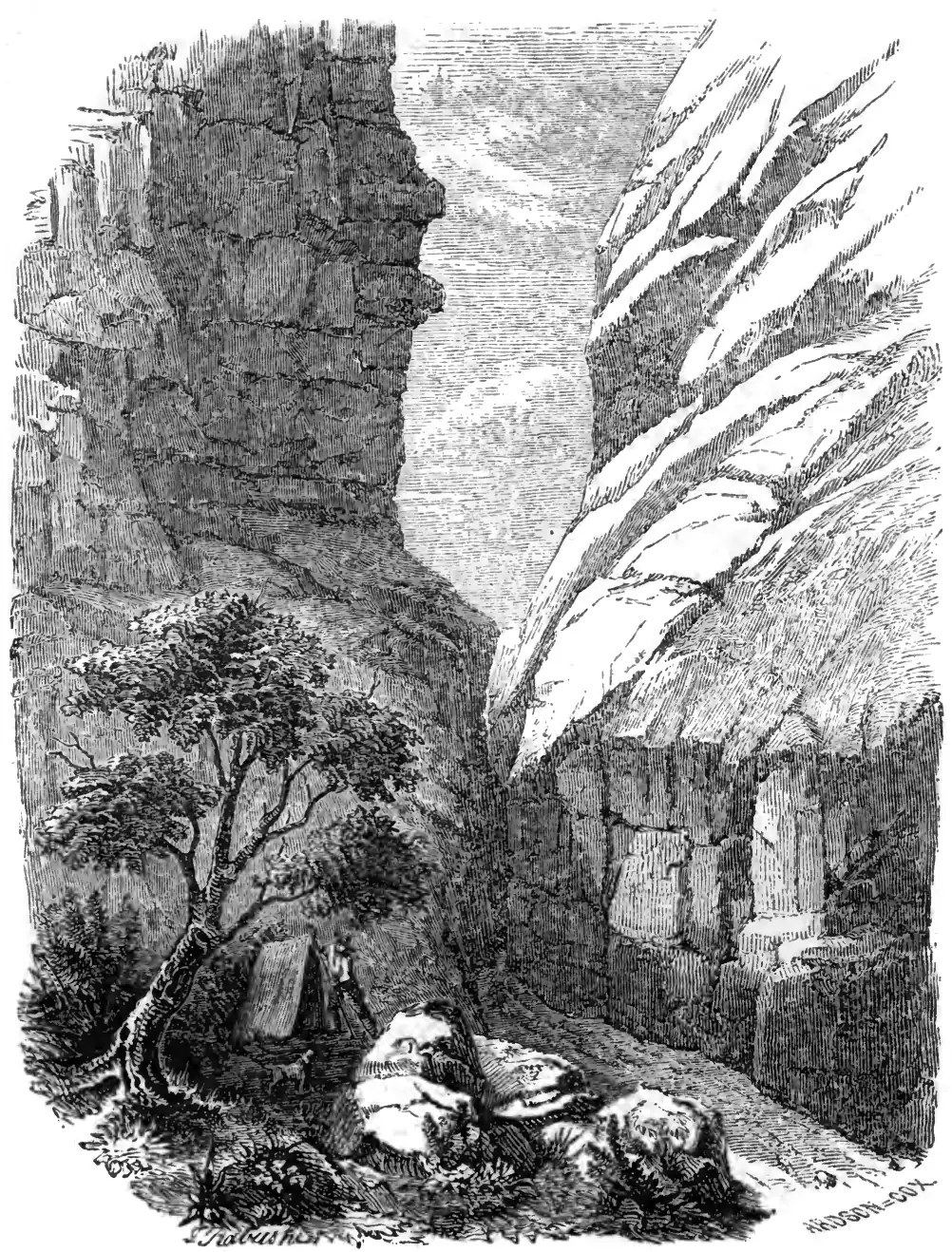

From the South Pass to the Wasatch Mountains, which bound the Great Basin on the east, the country consists mostly of rolling plains, quite similar to those over which we had passed. These mountains present the most fatiguing and difficult portions of the entire journey. It was, with few exceptions, a succession of steep ascents and descents, and narrow, rocky defiles; but the scenery was alternately beautiful and grand. The Spanish word cañon (pronounced canyon) is now the familiar designation of the narrow passes through  PARLEY'S CAÑON. the mountains. One of these, called Echo Cañon, is twenty-five miles in length, terminates on the Weber River, and furnishes a nearly level road the whole distance. This cañon is half a mile wide, is walled in by precipitous ridges, and the rocks, in many places, are worn into the same castellated forms so common in the vicinity of Scott's Bluffs. In one place the rocks were of a bright straw color, and the reflection produced a soft, yellow light. We finally descended into the Valley of Salt Lake, through Parley's Cañon, a dangerous pass, in places but a few rods wide, and walled in by rocks more than two thousand feet high. In a military point of view, these passes might be defended by a handful of resolute men against a host.

PARLEY'S CAÑON. the mountains. One of these, called Echo Cañon, is twenty-five miles in length, terminates on the Weber River, and furnishes a nearly level road the whole distance. This cañon is half a mile wide, is walled in by precipitous ridges, and the rocks, in many places, are worn into the same castellated forms so common in the vicinity of Scott's Bluffs. In one place the rocks were of a bright straw color, and the reflection produced a soft, yellow light. We finally descended into the Valley of Salt Lake, through Parley's Cañon, a dangerous pass, in places but a few rods wide, and walled in by rocks more than two thousand feet high. In a military point of view, these passes might be defended by a handful of resolute men against a host.

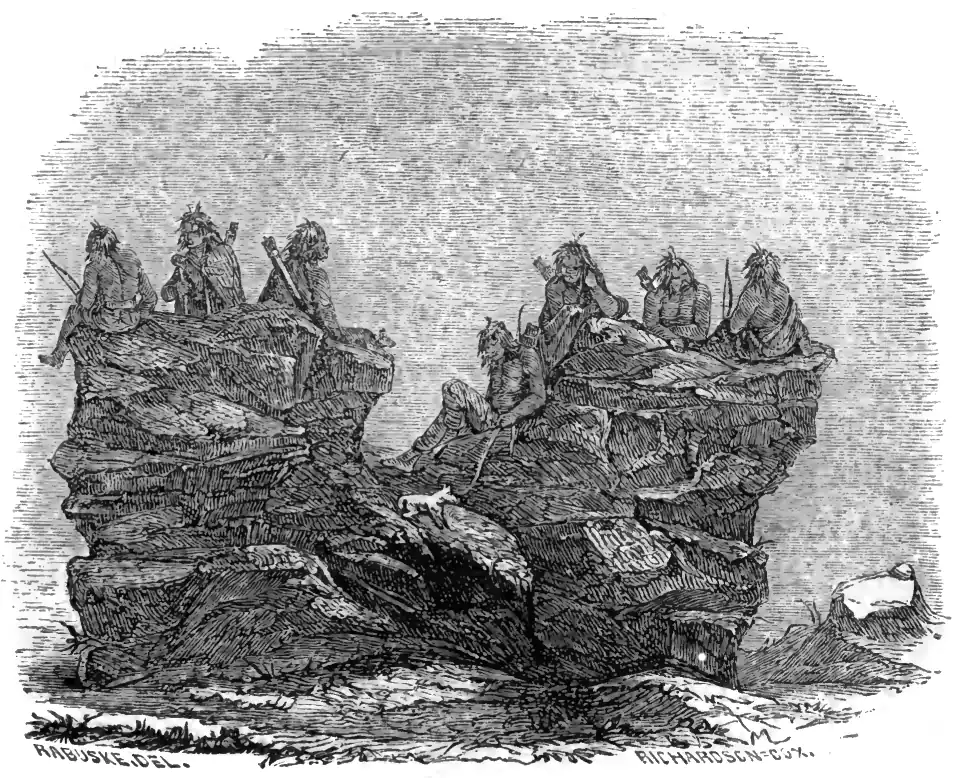

The whole route presents but few difficulties on account of the Indians. They are all inveterate thieves,

DIGGERS ON THE WATCH. from the Shawnees and Potawatomies, who are partially civilized, to the most degraded Diggers; and the traveler must use a reasonable degree of vigilance for the safety of his property. The Pawnees are the most dreaded of any on the route; they are fierce, active, and disposed to be mischievous when they encounter a small, unguarded party, and can safely gratify their thirst for plunder.

DIGGERS ON THE WATCH. from the Shawnees and Potawatomies, who are partially civilized, to the most degraded Diggers; and the traveler must use a reasonable degree of vigilance for the safety of his property. The Pawnees are the most dreaded of any on the route; they are fierce, active, and disposed to be mischievous when they encounter a small, unguarded party, and can safely gratify their thirst for plunder.

The Indians generally are the most troublesome beggars in the world, and will importune without ceasing, unless repulsed with some degree of sternness. While encamped one day near Fort Laramie, a large, well-formed Sioux, known by the name of "Old Smoke," stationed himself within a foot of me while eating dinner, and fixed his gaze upon the food with the eager expression of a hungry dog. At every mouthful he would say "goot," "groot." This was not very appetizing, so I gave the old rat a plateful on condition he would go away. He readily accepted the bribe, and went to another mess, where he played the same maneuver with success.

I must confess I have no very exalted opinion of the whole race. Their broad features, wide mouths, low foreheads, and black, snaky, venomous eyes, make up a collection of disagreeables which they manage to heighten by paint, filth, and outlandish ornaments. Their most stylish dandies might well be taken for escaped inmates of Bedlam. Our train passed two villages of Chyenes, in the vicinity of Fort Laramie—that is, two collections of lodges, made up of lodgepoles and buffalo robes or canvas. The whole concern poured out, men, women, children, cats, dogs, and horses, and surrounded us—some tricked out in all their scarecrow finery, and others ragged almost to nudity. They followed us, begging, hooting, screaming, howling, and. barking, for a mile. It might remind one of Old Picket's denunciation, in which, among other choice things, he hoped the soul of his antagonist might be chased "by a tanner's dog around the ragged ramparts of damnation."

It is no doubt the duty of philanthropists to continue their efforts to elevate the condition of the children of the forest and the plains; yet the task looks well-nigh hopeless. But few have improved under these benev olent teachings, and the balance seem destined to melt away before the vigorous advances of civilized races.