Utah and the Mormons/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II.

TERRITORY OF UTAH.

- The Great Basin: its geographical Features and Curiosities.

- Great Salt Lake.

- Utah Lake.

- Iron and Coal.

- Agricultural Capacities and Drawbacks

- Irrigation.

- Alkaline Salts

- Scarcity of Timber.

- Political Importance.

- Business

- Mr. Livingston.

- Great Salt Lake City.

- "Ensign Peak."

- Cities.

- Health.

- Improvements.

The Territory of Utah lies between latitude 37° and 42°, and is bounded on the west by the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, on the east by the summit of the Rocky Mountains, and contains about one hundred and eighty-eight thousand square miles. This area embraces within its limits not only the Great Basin, so called, but that portion of the valleys of

Green and Grand Rivers and their tributaries lying between the Wasatch and Rocky Mountains. The Great Basin constitutes a large, and decidedly the most interesting portion of this territory; and is, in more aspects than one, the greatest physical wonder of North America. Completely walled in by lofty mountains, some of which are perpetually robed in

VIEW IN THE SIERRA NEVADA.

snow, its streams and rivers flow into its own bosom, forming lakes of various dimensions, from which the confluent waters escape only by evaporation, or disappear in sandy deserts. That its entire surface has at some period been covered by a vast inland sea, there are many indications in the numerous water-marks which exhibit their traces in the mountain sides. The bench on the slope of which the Mormon capital is built, is a shore-mark which, in the clear atmosphere, may be traced by the eye south, along the base of the mountains, a distance of over twenty miles.

VIEW IN THE SIERRA NEVADA.

snow, its streams and rivers flow into its own bosom, forming lakes of various dimensions, from which the confluent waters escape only by evaporation, or disappear in sandy deserts. That its entire surface has at some period been covered by a vast inland sea, there are many indications in the numerous water-marks which exhibit their traces in the mountain sides. The bench on the slope of which the Mormon capital is built, is a shore-mark which, in the clear atmosphere, may be traced by the eye south, along the base of the mountains, a distance of over twenty miles.

The Great Basin has as yet been but partially explored. The Mormon settlements extend along the base of the Wasatch Mountains, from the northern extremity of Great Salt Lake to near the southern boundary of the territory, a distance of some three hundred and fifty miles. The usual emigrant route to California from Great Salt Lake City is around the northern extremity of the lake, and thence in a southwesterly direction down the valley of the Humboldt, or Mary's River, to Carson's Valley. The residue remains mostly unexplored. The portions known present bold and striking features, and great natural curiosities. It has lofty mountain ranges, rising to the clouds, some of which are perpetually capped with snow. The northern rim of the basin lies much farther south than appears from Fremont's map, published in 1849. In passing around Salt Lake on the route to California, the traveler crosses streams which flow into the rivers of Oregon, and does not pass the dividing summit until he has journeyed some forty to fifty miles south of the northern end of the lake. While toiling over these rugged elevations, the lover of natural scenery enjoys the grandeur of the prospect—a panorama of lofty ranges and peaks, glittering in the light of the sun, and extending in all directions as far as the eye can reach. Often sharp pyramidal peaks, rising abruptly, exhibit different kinds of rock, water-worn into turreted, castellated, and fantastic forms. The rocks are generally primitive, and the abundance of scoria gives evidence of the fiery throes which the earth has undergone in heaving up these tremendous elevations.

There is probably no part of the earth where so rich a field is presented for the researches of the naturalist. The valley of the Great Salt Lake is particularly prolific in natural curiosities. Springs, from the one hot enough to boil an egg in a few minutes, to the one of a temperature for a pleasant warm bath, occur every few miles; and these are generally impregnated with sulphur in combination with alkaline salts. Some of

HOT SPRINGS NEAR SALT LAKE CITY.

these springs, throwing out generous volumes of water, form ponds from one to three miles in circuit, in which may be found, attracted by the genial temperature, tens of thousands of water-fowl. Some of them are chalybeate, and coat the rocks and earth over which they flow with oxyd of iron.

HOT SPRINGS NEAR SALT LAKE CITY.

these springs, throwing out generous volumes of water, form ponds from one to three miles in circuit, in which may be found, attracted by the genial temperature, tens of thousands of water-fowl. Some of them are chalybeate, and coat the rocks and earth over which they flow with oxyd of iron.

Great Salt Lake is a very great curiosity. It is about one hundred and thirty miles long, and from seventy to eighty broad, and is, as near as may be, a vast collection of brine. The water seems to be saturated with salt to its utmost capacity of holding it in solution, indicating the neighborhood of great deposits of mineral salt. Between Great Salt Lake City and Bear River is a spring intensely salt, which pours out a volume of water equal to that at Spring Port, on the east side of Cayuga Lake, which it very much resembles. This is probably one of many others of a similar character which pour their contents into the lake. At particular points on the beach, where the regular course of the winds dashes up the waves, the salt collects in such quantities as to be conveniently shoveled into carts for domestic use. It is also procured by evaporation, three pails of the water producing one of salt. A person bathing may sit in the water, rising to his armpits, as in a chair; but let him beware of toppling over, unless he wishes to encounter the risk of drowning "heels over head." The water is perfectly limpid, and has no living thing beneath its saline waves. It has many islands with high mountain peaks, among the largest of which is Antelope Island, situated so near the eastern shore as to be accessible for grazing purposes, for which it is extensively used.

Utah Lake, about forty miles south of Salt Lake, with which it is connected by its outlet, the River Jordan, is a handsome sheet of fresh water, some fifteen miles long by ten broad, and abounds with the finest salmon trout. In approaching it from the north, the valley of the Jordan narrows, and in rounding a point about seven miles from the lake, a grand spectacle suddenly bursts upon the view of the traveler. The lake presents itself in placid beauty below him, surrounded, and seemingly completely walled in, by lofty mountains covered with snow; and it is not until he makes its circuit that he discovers a broad belt of level arable land between the lake and these mighty elevations; nor does he till then perceive the tremendous gorges through which flow the Provo River, the Spanish Fork, and other streams. The cañon of the Provo is so deep and extended that a strong wind often pours through as from the nozzle of a blacksmith's bellows, which is felt for a distance of over two miles in passing its mouth.

The Great Basin is rich in minerals, among which are iron and coal, found in Iron county, some two hundred and fifty miles south of Great Salt Lake City, in such abundance as to provide an adequate supply for the future wants of the population. Iron has hitherto been supplied from the thousands of wrecked and abandoned wagons which line the road nearly the whole distance from Missouri to Oregon and California. Gold has only been discovered in Carson Valley, near the line separating Utah from California, but there are strong indications that it abounds in other portions of the Territory.

In regard to agricultural capacity, waste undoubtedly predominates over fertility, except in river bottoms, or in localities favorable for artificial irrigation. The Wasatch range contains a vast number of deep and rugged gorges or cañons, through each of which tumbles a mountain stream, fed partly by springs, but mostly by melting snows. Wherever one of these streams rushes out upon the plains, the agriculturist can turn it to use in bringing forth the fertility of the land. Without this aid he would plow and plant in vain, owing to the sandy nature of the soil and the long summer droughts. All the products of the States in the same latitude can in this mode be raised in great perfection. The vegetables are large, and generally of superior quality. Those portions of the basin not in the immediate vicinity of rivers and streams will probably be found entirely unfit for cultivation.

The farmer in Utah is subject to some heavy drawbacks. The necessity of irrigation imposes no trifling addition to his labors; water-ditches are to be cut over and through his land, and great care is necessary in their proper management. In some places where water is not abundant, the neighbors use it alternately, and spend the night as well as the day in distributing the precious moisture over their fields.

Again, the temperature is subject to very sudden changes. The lowest valley in this elevated region is some four thousand feet above the level of the ocean, and the surrounding mountains run up four to six thousand feet higher, the tops of which are covered with snow during a large portion of the year. Of course, the shifting winds from these snowy points are not only violent, but of an icy temperature, and the consequences are early and late frosts, and often a chilly atmosphere in the very midst of summer. The winds blow frequently with great violence, bringing up now and then terrible storms, accompanied with thunder and lightning. It is said the wind is sometimes so high as to bring spray from the lake to the city, a distance of twenty-two miles!

Another serious drawback is the abundance of alkaline salts, or saleratus, in the soil. This is a marked peculiarity throughout the whole territory, as far as explored. Sometimes it shows itself in a white efflorescence on the surface of the ground, covering whole acres with the appearance of a heavy white frost or slight fall of snow, and lumps are frequently picked up for domestic use. Many of the streams are so strongly impregnated with it as to make it dangerous for cattle to drink from them. Between Salt Lake City and the lake, numerous pools and small ponds of water may be found of the color and nearly of the taste of common ley, from the same cause. This property in the soil is beneficial to the grasses, and makes the extensive pasture ranges equal to the salt marshes on the Atlantic coast for cattle. So abundant are these salts, that the whole vegetable kingdom is more or less affected by them; some, as potatoes, squashes, and melons, are rendered sweeter and more palatable. The common pie-plant loses almost entirely its acidity. Wherever it is sufficiently abundant to effloresce upon the surface, it totally destroys vegetation; and I heard of sundry fields of wheat being injured, and some totally ruined, by its sudden appearance after the crop was half grown. In some cases, a good crop will be raised one season on a piece of land, and the next be entirely destroyed from this cause; and many of the inhabitants believe that it can not be exhausted by repeated cultivation.

Sugar beets are raised in such size and quantity as to suggest the idea that they could be made available in the manufacture of sugar. Upon this suggestion, a large quantity of machinery for the purpose was purchased in Europe in 1852, and taken over the Plains in the fall of that year. The whole expense exceeded $100,000, and was contributed principally by Mormons abroad, in connection with some having capital, who had but recently gathered with the Saints, under strong encouragements held out that it would be a profitable investment. The machinery was put into partial operation in the winter and spring of 1853, and, owing partly to want of skill in the workmen, but mostly to the fact that the beet was found to be strongly impregnated with alkaline salts, the article manufactured so far has been miserably poor, and the concern is likely to prove an unfortunate failure.

Another drawback arises from the great scarcity of timber. The Valley of Salt Lake is nearly as bare of trees as though it had been blasted by the breath of a volcano. A few of the mountain streams are skirted with a scanty growth of cotton-wood and aspen; some of the cañons have a small quantity of maple; and the mountain sides are sparsely supplied with stunted cedar and pine. Wood for fuel in the city can only be obtained by a cartage of about fifteen miles, from places of difficult access, and the price ranges from ten to fifteen dollars per cord. Timber for fencing, building, and mechanical purposes, is equally difficult to be obtained, and bears a corresponding price. The evil, too, is increasing; the supply is becoming more and more scanty, and in comparatively a few years, unless the coal can be brought into general use, the expenses of living, from this cause alone, must be greatly enhanced. The Mormons are looking forward to the period when a rail-road, constructed from the iron found in Iron county, will be the means of distributing the coal found in the same region. Some efforts have been made by way of encouraging the manufacture of iron, and the excavation of the coal-beds, but they are feeble and tardy. The Saints are at present too much engaged in building the Temple to devote their whole energies to the development of the resources of the Territory. They have a very convenient place of worship; and it might seem that the Temple, which, from the plan of its construction, promises to cost a round million, might be postponed to the growing necessity for a permanent supply of fuel. But it is to be noted that one item of their creed is, that their friends who have died out of the pale of the Church may be baptized by proxy, and thus saved from Purgatory; and that this baptism can not effectually be performed except in the Temple. It is hard to have friends in infernal durance, but most people would let them roast a little longer, rather than run the risk of freezing themselves. Those who put faith in this absurdity are, of course, under the strongest possible impulse to go on with the structure; and those who do not believe in it, believe, nevertheless, that the Temple will form a nucleus around which the Saints can be gathered without danger of dispersion.

In a political point of view, the settlement of this isolated region has been, and will continue to be, of great importance, as the half-way house between the eastern and western portions of the continent. The emigrant, on his tedious journey to Oregon or California, becomes weary and dispirited when he reaches this point—his cattle worn down, his wagon broken, and his provisions exhausted. Here he can recruit, and lay in new supplies; and it seems as if Providence had overruled the Mormon fanaticism to the performance of uses in this respect, little dreamed of by the fugitive Saints when they made it their abiding-place. The benefits derived from this source have very much promoted the prosperity of the Mormons, by making a market for their surplus grain, and furnishing them with supplies otherwise difficult for them to obtain. In 1850, the emigrants were very numerous, and their wagons, cattle, tools, farming utensils, and household furniture, which were got along to this point, were sold to the inhabitants at the lowest rates in exchange for pack-animals and provisions. Many emigrants, too, every year, become utterly destitute at this point, and are compelled to labor for the means of further prosecuting their journey. Hundreds remain all winter, and work for a bare living; and a large number of the indications of industry and enterprise, in the form of buildings, fences, water-ditches, and other improvements, for which the Mormons have received credit, owe their existence to the toil of these temporary sojourners.

The legitimate business of the country is grazing. It is an inland region, pent up between lofty mountains, and is, and always must be, without commercial facilities. Its rivers are scarcely navigable to any extent, and its lakes can never connect points of sufficient importance to make them available in this respect; but there are thousands of acres which produce, in great abundance, nutritious grasses, upon which cattle, horses, and mules can subsist and thrive the year round. The worn-down animals of emigrants are purchased at low rates, and, after being recruited upon these extensive ranges, are driven to a sure and profitable market in California, where enormous profits are usually realized. Some of the finest breeds can now be found in Utah; and this business is beginning to be appreciated as the most lucrative in which the inhabitants can be engaged.

The shrewd merchant lays in at St. Louis a stock of goods adapted to the wants of the people of the Basin, fits up a train of wagons, to be drawn by oxen or mules, and wends his way to the Mormon capital. At Salt Lake, in exchange for goods at handsome profits, he collects a drove of cattle, horses, and mules for California. Hundreds of able-bodied men, wishing to seek their fortunes in the great El Dorado, can be had for the mere victualing, to assist in conducting such a train; and the entire expenses of the adventure sink into insignificance in comparison to the heavy profits realized in the great western market. Mr. Livingston, of the firm of Livingston and Kinkead, may be mentioned as a pioneer in these bold enterprises. He established himself at Salt Lake City in 1849, in an adventure of this description, which seemed doubly hazardous to his friends, from the remoteness of the region and the character of the inhabitants. It was an experiment, but he plunged boldly into it; and by liberal dealing, strict mercantile honor, great firmness, and far-reaching sagacity, has, though anti-Mormon so far as religious views are concerned, gained a healthy influence with the population, and established this kind of business upon its proper basis. His numerous adventures by "flood and field" make him an interesting companion; and many, compelled to a winter's residence in that out-of-the-way part of the earth, have been laid under deep obligations for his numerous kindnesses.

If the design of the Mormon rulers in selecting the Great Basin as the seat of their power was to isolate their people from the rest of the world, they certainly made a happy choice. The Mormon capital is unapproachable from any civilized point except by a tedious journey of from eight hundred to one thousand miles. In a severe winter it is entirely inaccessible: the mountain passes then lay in so bountiful a supply of snow as to set human perseverance at defiance; and the luckless sojourner, who has been accustomed to his daily paper, must content himself with speculations as to events transpiring in the outside world for three or four months. This isolation has its conveniences and inconveniences; it protects the Saints from Gentile influence or persecution, and enables the leaders to carry out, without let or hinderance, the most singular experiments upon human superstition and credulity which have been witnessed since the Dark Ages. But the expenses of living are great: every thing which can not be raised from the soil, and which the customs of civilized life have rendered necessary to cat, drink, and wear, cost at least four times as much as in the States, owing to the great land transportation.

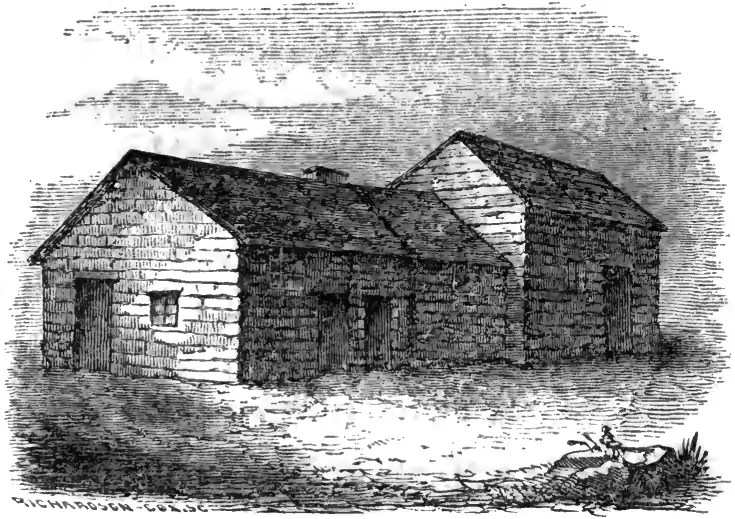

Great Salt Lake City presents a very singular appearance to the eye of a stranger. It is built of adobe or sun-dried bricks, and is of a uniform lead color, with the single exception of the house of Brigham Young, the prophet and seer, which is white, and standing on the most prominent point in the city, may be seen at a great distance. The streets are eight rods wide, and cross each other at right angles. Each block contains ten acres, and is divided into eight lots of an acre and a quarter to a lot. Of course, the city, which contains a population of about eight thousand, is scattered over a very large area. It is built partly on the slope of the lowest mountain bench, at a point where the Wasatch range turns to the north after running six or seven miles westerly, and is twenty-two miles east from the lake. A mountain stream called, "City Creek," originally ran through the centre of the town, but by numerous ditches its water is distributed through almost every street, according to the inclination of the land. The buildings are very ordinary in their style of construction, generally of one story, and are, many of them,

MORMON НАRЕМ.

mere huts. It is not uncommon to see a long, low building, with from two to half a dozen entrances, which is a sure indication that the owner is the husband of sundry wives, after the fashion of the prophet Joseph. There are a few dwellings of a larger class and fair appearance, among which are those of Brigham Young, already mentioned, Heber C. Kimball, Parley P. Platt, Ezra T. Benson, and other dignitaries of the Mormon hierarchy.

MORMON НАRЕМ.

mere huts. It is not uncommon to see a long, low building, with from two to half a dozen entrances, which is a sure indication that the owner is the husband of sundry wives, after the fashion of the prophet Joseph. There are a few dwellings of a larger class and fair appearance, among which are those of Brigham Young, already mentioned, Heber C. Kimball, Parley P. Platt, Ezra T. Benson, and other dignitaries of the Mormon hierarchy.

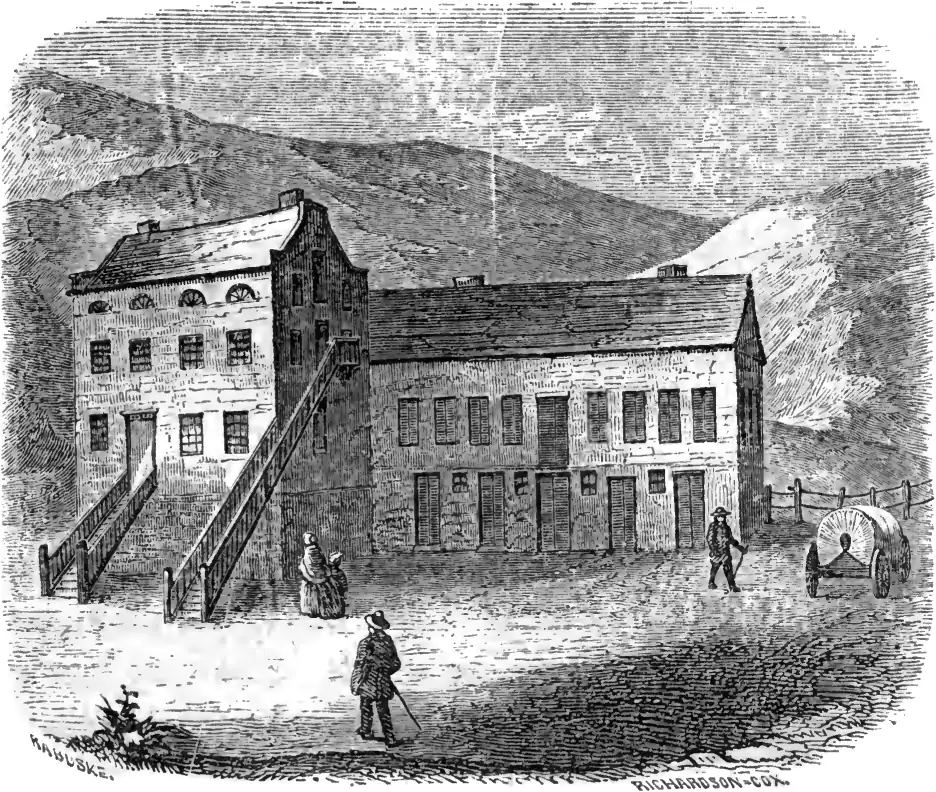

The public buildings are few—the Council House, where the Legislative Assembly and courts are held; the Tithing-office, where tithes are received, in a room

TITRING-OFFICE.

of which is the Post-office; the Social Hall, where theatrical performances are had, and in which the Saints are accommodated with conveniences for dancing and social parties; and the Tabernacle, a long, low building on Temple Block, the Mormon place of worship, very large on the ground, and capable of seating an audience of three thousand.

TITRING-OFFICE.

of which is the Post-office; the Social Hall, where theatrical performances are had, and in which the Saints are accommodated with conveniences for dancing and social parties; and the Tabernacle, a long, low building on Temple Block, the Mormon place of worship, very large on the ground, and capable of seating an audience of three thousand.

Temple Block contains the usual complement of eight acres, and, besides the Tabernacle, has a range of work-shops belonging to the Church, in which various mechanical employments are carried on. A wall is being built around the whole block, and excavations were commenced in the spring of 1853 for the erection of a temple which is to be the future glory and pride of all Mormondom. It is designed to be two hundred and twenty feet long by one hundred and fifty wide, with walls six feet thick. The excavation in the centre for a baptismal font is twenty feet deep. This grand structure is building, as all credulous Mormons believe, after a plan revealed to the prophet Brigham from heaven, and is to consist of three parts, corresponding to the sun, moon, and stars, which are the three glories or degrees of salvation in store for all true Latter-day Saints.

North of the city is a singular conical-shaped point called "Ensign Peak," which may be reached by a fatiguing walk of about two miles. This prominence must be about four thousand feet above the plain, and commands a magnificent prospect. The city lies beneath as on a map: the Jordan may be traced, like a small silver thread, winding its way through the valley until lost in the lake; the latter is seen to stretch away in the distance between the islands which rise from its bosom; beyond may be seen a snowy range, which the traveler must surmount in his journey to California; and in a southern direction, mountains are beheld to rise above mountains far beyond Utah Lake, clothed in their everlasting mantle of white, the whole leaving upon the mind of the beholder an impress of grandeur which language utterly fails to describe.

The Mormons make a formidable display of cities upon paper. Great Salt Lake City contains about 8000 inhabitants, Provo some 1400, and Springville about 700. Aside from these, their cities are greatly more distinguished for the oddity of their names than the number of their citizens—such as Lehi, Manti, Nephi, &c.—names which belonged to various worthies who figured in the history of by-gone things supposed to have been exhumed by the prophet Joseph. Another oddity is, that these cities are accommodated with the very longest acts of incorporation, embracing all the municipal machinery of mayor, aldermen, police justices, provisions regulating hacks, lighting streets, sewerage, and other things too numerous to mention —something like the rustic grandson incased in the long-tailed coat of his ancestor, greatly too large for his dimensions. The city of Lehi, on Utah Lake, which I was enabled to visit, is a fair sample of the rest; some twenty wretched mud huts, scattered over an area of two or three miles, with a population not exceeding one hundred, made up the whole affair. Why the Saints take so much pains to make cities upon paper, unless by way of "handbill" to convey exaggerated notions abroad of their progress and prosperity, it is very difficult to perceive. The entire population of the Territory in the spring of 1853 could not have varied much from twenty-five thousand; Orson Pratt, in "The Seer," states it at from "thirty to thirty-five thousand."

From its great elevation, and pure and bracing atmosphere, any one, reasoning from natural causes, would expect to find the Valley of Salt Lake one of the healthiest regions in the world. The very reverse, however, seems to be the case. Sickness is very common, and mortality great. The report of the Superintendent of the Census for December, 1850 (p. 140), exhibits Utah the very lowest in the list of comparative health of all the states and territories except Louisiana. That such a result can not be owing to the privation and suffering incident to new settlements by emigration, is evident from the fact, that while one death occurred in 4761/100 in the population of Utah for the year ending June 1, 1850, only one in 23282/100 occurred in Oregon. Whether it is the fault of the climate and the qualities of the soil, or of the peculiar customs and habits of the people, remains to be tested by further observation. All these causes may have their agency in the result.

The alkaline properties of the soil are, with good reason, supposed to promote erysipelas and scrofulous diseases. The gross sensualities originating in polygamy, coupled with parental neglect of offspring, occasion great mortality among children. To these may be added intemperance in drinking, very generally diffused, and which finds its gratification in a miserable article of whisky and beer, manufactured in great quantities.

When we regard the extended settlements made, the lands brought under cultivation, and the cities built within a brief period in this heretofore desolate region, it seems to us next to miraculous, and we are very much inclined to look upon the Mormons as an uncommonly industrious and enterprising race of men. Much, however, is due to emigrant labor, already alluded to, and much more to the effect of contrast. After passing over the Plains, and for weary days and weeks meeting with no human habitations but Indian lodges, Canadian-French trading-posts, and two military stations, the traveler is greatly delighted when he descends into the valley through one of the tremendous mountain gorges, enters a regularly-built city, and finds the necessaries and many of the luxuries of civilized life. All is for a time coleur de rose, and his descriptions are apt to be tinged with a similar hue. The mere surface of society is found to be similar to that of many other recently-established communities, and it needs a residence of more than a few days or weeks to lift the curtain and view things as they are.

Without detracting in the least from the commendable enterprise of the Saints, it may reasonably be said that any other body of American farmers, mechanics, artisans, and laborers, of equal numbers, would have effected more, because the means expended in the erection of the temple, and in the support of a numerous priesthood with their harems, would be turned in a more useful direction. Much of the marvel lies in two facts: first, the entire community have been transferred there nearly at once, without waiting for the tedious process of a gradual settlement; and, second, all their energies, stimulated by religious enthusiasm, have been measurably directed by a single will. The real miracle consists in so large a body of men and women; in a civilized land, and in the nineteenth century, being brought under, governed, and controlled by such gross religious imposture. As the Great Basin is the greatest physical, so its inhabitants may be said to be the greatest moral, curiosity of the New World.